Trump can’t postpone the election, but officials worry he and the GOP could starve it

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The elections chief in the Detroit suburb of Rochester Hills, Mich., a competitive softball player in her younger days, feels like she’s been pushed back into the batting cage. This time, nobody is giving Tina Barton a bat.

“It is like I am just standing there without anything to hit the balls back,” Barton said. “Every day I step in, and something new is coming at me at high speed.”

Poll workers quitting. A churn of court decisions throwing election rules into tumult. A COVID-19 outbreak at City Hall that could sideline her department at a critical moment.

The viral pandemic has put the nation’s election system under a level of stress with little precedent.

And, although figures in both parties rejected President Trump’s suggestion of postponing the November election when he flirted with the idea Thursday, they haven’t provided the money that officials like Barton need to get ready for it.

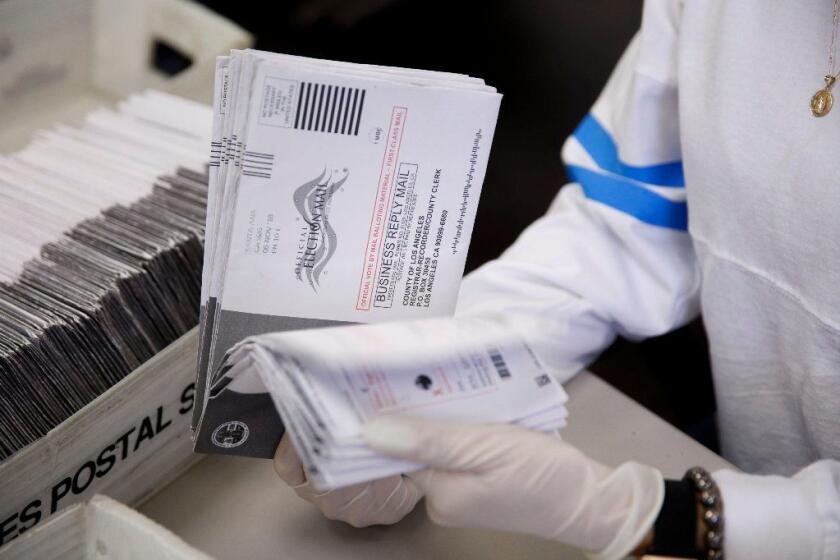

The House months ago approved $3.6 billion to aid local and state elections officials in dealing with an expected flood of mail-in ballots this fall, something that threatens to overwhelm elections officials in states where voting by mail is a relative novelty. The money has stalled in the Republican-controlled Senate — part of the larger stalemate over a new round of help for people and businesses devastated by the economic impact of the pandemic.

- Share via

President Trump on Thursday suggested delaying the November election as he continued to raise the false specter of widespread voting fraud.

“Elections officials need that money yesterday,” said Justin Levitt, an associate dean at Loyola Law School who worked on voting rights enforcement at the Justice Department during the Obama administration. Considering the trillions Congress is spending to shore up the economy and public institutions, it is bewildering that lawmakers are balking at the few billion needed to keep elections functional, he said.

Voting by mail works smoothly in states, mostly in the West, that have had years to hone their procedures. But in places that are now hurriedly trying to improvise, problems became clear during primary elections this spring and summer. Administrative dysfunction and fights over voting rules left tens of thousands — predominantly voters of color — disenfranchised as voting systems buckled under the strain.

“I fear we are bracing for disaster unless there is intervention by Congress and states are given the resources they need to get this right,” said Kristen Clarke, president of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law.

“We saw long lines in cities across the country in primaries. Those lines could be 10 times longer in some communities.”

In states where voting went awry during the primaries, Black communities tended to suffer the most.

In Wisconsin, for example, the overwhelmingly white city of Madison managed to open 66 polling sites. Milwaukee, more than twice the size and 40% Black, had just five sites open.

Although voter turnout was up overall in Wisconsin compared with previous primaries, the state failed to get mail-in ballots to many voters in time, and officials concede that the delays disenfranchised thousands.

The pandemic may be amplifying barriers to voting that lawmakers had put in place earlier. These barriers — which include requirements in some states that absentee ballots have witness signatures, that voters include a copy of their identification with their mail-in ballot, and that nobody but the voter may deliver their ballot to a polling place — tend to have a disproportionate effect of suppressing the Black vote.

“The primary demonstrated the tremendous damage to communities of color,” said Michael Zubrensky, chief counsel for government affairs at the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights.

Georgia, which has frequently had problems with its elections, once again had some of the nation’s worst failures during the primary season. Malfunctioning voting machines, lack of preparation for the surge of absentee ballots and closure of polling places all contributed to chaos in the state’s June 9 primary.

COVID-19 has led to a push for vote by mail, but advocates face logistical and legal hurdles — and “rigged election” claims from President Trump.

Some voters waited in line for seven hours. Hundreds of thousands of absentee ballots were not delivered on time. In Georgia as in other states, the fact that Black and Latino communities have been especially hard hit by the virus made staffing polling stations in cities a much bigger challenge.

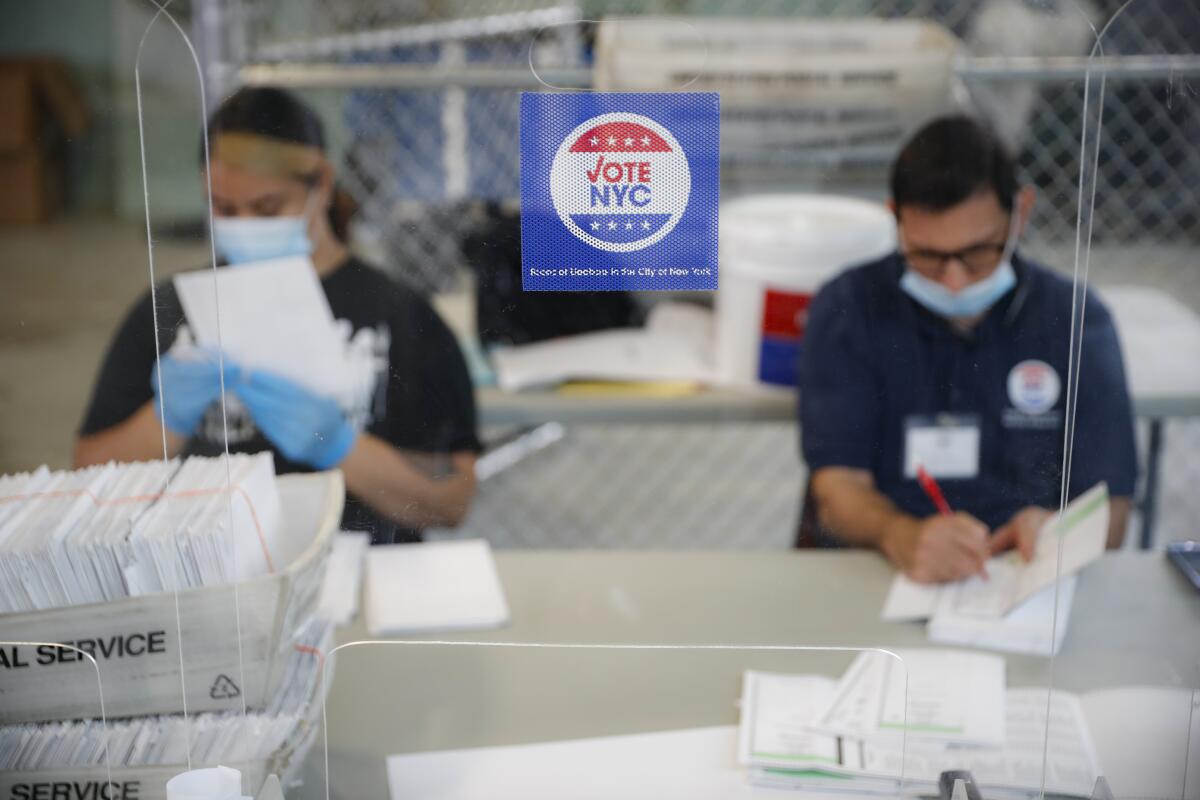

In other states that are not used to voting by mail, the problems haven’t been primarily with casting ballots, but with counting them.

In New York, for example, results in several close congressional primaries have been delayed for weeks as elections officials struggle to handle an unprecedented flood of mail ballots.

Many election experts fear that if the November election ends up being close, a slow count will provide fuel to conspiracy theories and efforts by Trump to delegitimize the result if he loses.

Moreover, lack of voter education about how to fill in and mail absentee ballots — rules that vary by state — put many inexperienced voters at risk of not having their ballots count. In some states, the rate of ballots that are rejected has soared.

As elections officials absorb the harsh lessons of the primaries, legal battles over voting rules breaking out all over the county have further complicated the picture.

Already, 166 cases have been filed nationwide, according to a tally Levitt is keeping. Many of them are disputes between Democrats who believe it is to their advantage to make casting a ballot as easy as possible and Republicans who argue that the pandemic is not suitable cause to relax what they see as anti-fraud measures.

The resulting court rulings are whipsawing beleaguered elections offices.

In Virginia, for example, a consent decree for the primary waived the requirement that absentee voters get a witness to sign their ballots. But the requirement is back in place for the general election — for now. The court fight goes on.

“We don’t know how that will turn out,” said Brenda Cabrera, director of elections in the city of Fairfax. She said if her office starts mailing voters ballot instructions “ and the rule changes, we have a problem.”

During local elections in May, when witnesses were required, some voters who lived alone drove to her office in their desperation to vote.

“They had nobody else who would be their witness,” Cabrera said. “We would go out with masks and gloves and do it.”

The flood of dollars that supporters of both parties are pouring into fights over election rules is often driven by belief that the outcome could help one party over another. Amid the pandemic, however, those calculations often aren’t panning out.

A network of deep-pocketed progressive donors is launching a $59-million effort to increase the number of people of color who vote by mail.

Trump’s crusade against mail-in voting, for example, seems to be backfiring in some key places.

In Florida, Republicans long held an edge in absentee voting that has now vanished as the party’s voters heed the president’s advice not to trust voting by mail.

Enthusiasm for voting by mail is fast fading among Republicans in other states, as well, according to Charles Stewart III, an election administration expert at MIT.

“I find Trump’s statements baffling,” said Richard L. Hasen, an election law scholar at UC Irvine. “They may make it harder for his supporters to vote.”

All the turmoil alarms Levitt. He likens U.S. elections to a durable water balloon, with lawmakers and attorneys pushing the water in one direction or another as they constantly change the rules. But the strain of the pandemic, he warned, has left the balloon extremely fragile.

“If you keep pressing too hard on that balloon, it breaks,” he said. “And it breaks for everyone.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.