Were Joan Didion and Eve Babitz really two sides of the same coin?

- Share via

Book review

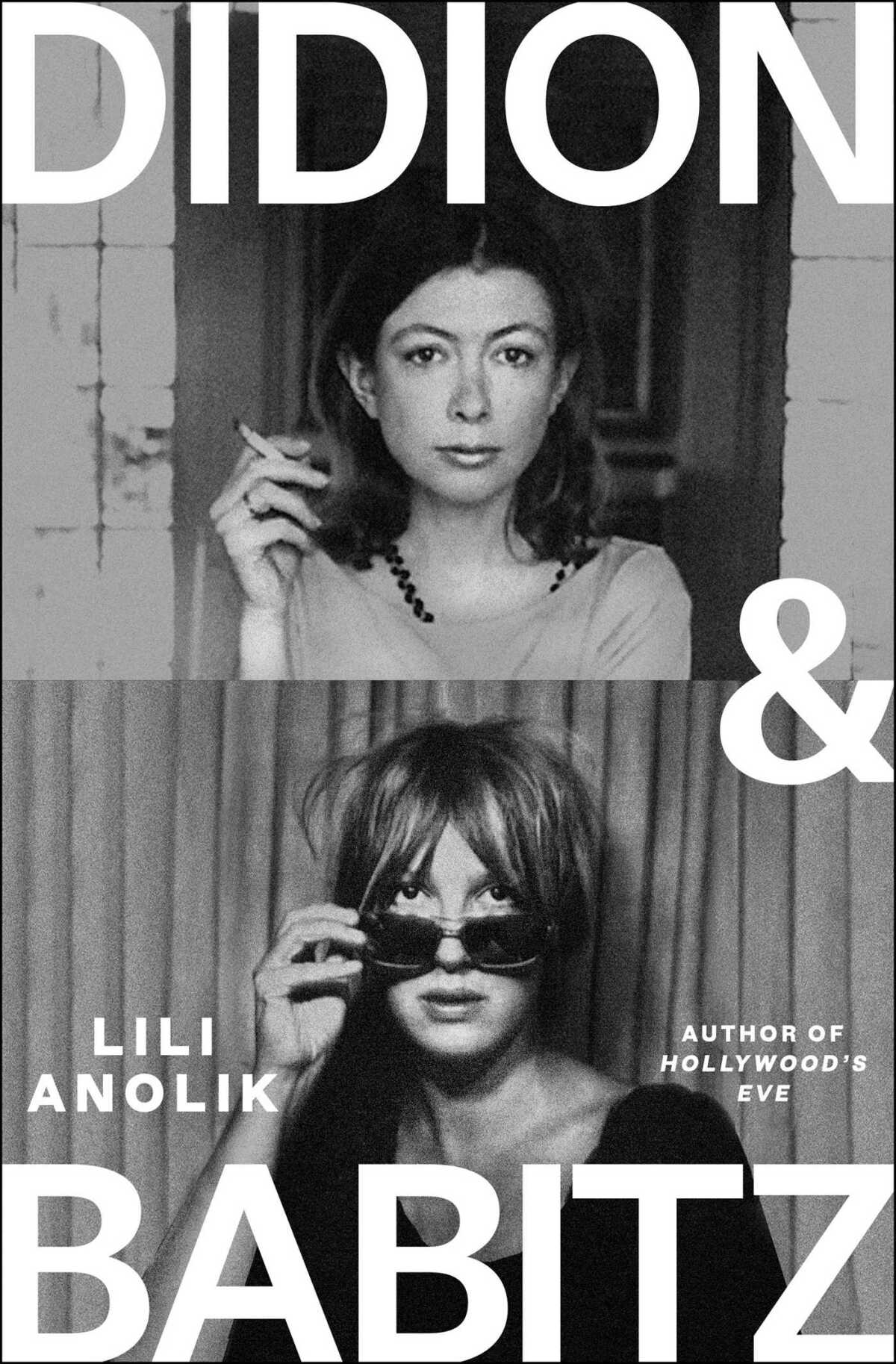

Didion & Babitz

By Lili Anolik

Scribner: 352 pages, $29.99

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

When I first cracked open Lili Anolik’s dazzling and provocative “Didion & Babitz,” I was dubious. The opening pages have a breathy, adulatory quality that made me think “fangirl.” And for about 60 pages, as Anolik recalls her first encounter with Eve Babitz’s work — a random quote that sent her down the Google rabbit hole — and reprises what captivated her, I remained skeptical. Could Anolik add anything meaningful to the oeuvre she’d already produced, including the stunning 2014 Vanity Fair piece in which she outs Babitz as her newfound idol, a secret genius whose obscure literary output deserved a renaissance? Anolik followed that in 2019 with a passionate immersion into Babitz’s life and persona, the book “Hollywood’s Eve,” which celebrates and psychoanalyzes Babitz as a cultural icon who hasn’t gotten her due.

I’d been among those who’d flocked to reissues of Babitz’s “Slow Days, Fast Company” and “Sex and Rage,” among the out-of-print titles that were revived following the Vanity Fair article. I was riveted by her semiautobiographical, fictive chronicles of the glamorous and seedy post-’60s Hollywood scene in which she was a key, but unsung, player.

Babitz’s prose stood in stark contrast to that of her friend and contemporary Joan Didion. Didion’s is cool and analytical, like the image she carefully cultivated, turning a skeptic’s gaze on California culture. Babitz’s literary style, on the other hand, reads as uninhibited, exuberant, decadent. For all its sensuousness, though, there is an innocent, unstudied quality, and for Babitz, L.A. is an irresistible mecca with its ruthless transactions over beauty and power and its intoxicating bougainvillea. Babitz had experienced New York City and knew that East Coast artists and intellectuals looked down their noses at Tinseltown, but she was Hollywood’s most ardent defender and willing participant. She threw herself into the fray with abandon, posing nude for a photo with Marcel Duchamp; taking lovers by the score, among them Jim Morrison, Harrison Ford and Steve Martin (who gave her a Volkswagen) — all on the cusp of fame. She dabbled in art, creating album covers for the likes of Buffalo Springfield and Linda Ronstadt.

Born in 1943 and coming of age just as the sexual revolution was unfolding, and before AIDS put the brakes on it, Babitz reveled in her abundant sensuality. Enamored of the artists flocking to Hollywood, “sex was how she showed her appreciation.” She was “astonishing, reckless, a wholly original personality” aided in her seductions by being a “concupiscent creature.” Her beauty, as well as her preoccupation with men and drugs, often led her hazy career aspirations astray.

Once Anolik completed “Hollywood’s Eve,” she hoped the book would serve as a kind of “auto-exorcism” closing the chapter on her decades-long obsession with an L.A. icon. But Didion, ever a powerful influence, brought Anolik back.

In 2021, Anolik received a call from Babitz’s sister, Mirandi. Eve, now in her 70s, had long been suffering from the effects of third-degree burns (the result of a fire caused by lighting a Tiparillo cigar while wearing a gauzy skirt!), as well as the onset of Huntington’s disease. She and her sister had made the difficult decision to move Eve into assisted living. While clearing out Eve’s filthy, cluttered apartment, Mirandi came across a box filled with letters Eve had written and received. She invited Anolik to pore through them with her at the Huntington Library, which acquired Eve’s archives. Anolik hopped a plane from New York to California the next morning.

Didion’s most famous essay was about my mother’s murder trial, set in California’s broken dream. It turned out to be right.

The first item Anolik retrieved from the box erased any chance she would relegate Babitz to the back shelf. It was a compelling letter from Babitz to her friend-turned-frenemy Joan Didion, who had helped Eve establish connections in book publishing and edited her first book. In the intervening years, while Didion choreographed a brilliant career, Babitz circled fame but couldn’t close the deal. The letter’s subject was ostensibly Didion’s contempt for Virginia Woolf and the goals of the women’s movement, but in its “subtly vicious” digs at Didion’s more clinical approach to writing, it came across to Anolik as “the way you talk to someone who’s burrowed deep under your skin, whose skin you’re trying to burrow deep under.” Anolik writes that reading it was like “hearing a conversation I wasn’t supposed to hear, and my eyes listened ravenously.” With hundreds of additional pieces of correspondence now at her disposal — involving Joseph Heller, Jim Morrison, Didion and others — a new window into Babitz’s world had opened.

In the literary arena, Didion took the lead, outperforming the friend she helped get published. Along with her astonishing prowess, Didion was everything Babitz wasn’t: disciplined, calculating, protective of her talent and of whom she allowed to safeguard it. Anolik tries to make the case that Babitz and Didion — who died about a week apart in 2021 — are yin and yang, two sides to the same coin, thus the thesis for her riveting book. My takeaway, though, is that Anolik remains in thrall to Babitz. The correspondence and contacts she’s accessed — which do contain irresistible nuggets, such as claims that Didion’s husband, John Gregory Dunne, may have preferred men, or that Didion’s one true love was someone other than her spouse — are bit players in the larger production: Babitz refuses to leave the stage. Didion may be the more esteemed figure, but she’s not the one who captures our imaginations in Anolik’s telling.

And I can’t blame Anolik for once more shining the spotlight on Babitz. Her heroine is endlessly fascinating — admirable, self-destructive, loving, frustrating, ingenious, her bright light largely extinguished by “overindulgence, profligacy and promiscuity, reckless and spectacular consumption” — not to mention a hereditary disease, the lack of a killer career instinct, and a generous spirit that led to many disappointments. In this character study, Didion is more of an afterthought.

As I turned the pages of “Didion & Babitz,” I found myself cheering on Anolik’s decision to make one more foray into Babitz’s glittering, free-falling, unencumbered yet troubled world. Would I want my daughter to follow Babitz’s path or Didion’s, if given the choice? Probably not Babitz’s. But what a ride.

Leigh Haber is a writer, editor and publishing strategist. She was director of Oprah’s Book Club and books editor for O, the Oprah Magazine.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.