Joan Didion, masterful essayist, novelist and screenwriter, dies at 87

Didion bridged the worlds of Hollywood, journalism and literature in a career that arced most brilliantly in the realms of social criticism and memoir.

- Share via

During a reporting trip to San Francisco in the late 1960s, Joan Didion happened upon a 5-year-old girl in a Haight-Ashbury crash pad who described herself as being in “High Kindergarten.” What the child meant, Didion later wrote, was that she was high on acid, apparently not for the first time.

Whether she said it with irony was not noted in Didion’s cool retelling in “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” her classic piece about societal disarray in the psychedelic era. But the memory of the encounter made the author momentarily speechless when an interviewer asked her about it decades later.

For a few moments she could only raise her arms beseechingly, like a wizard summoning powers, before the words finally burst out.

“Let me tell you,” she declared in the 2017 documentary “Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold,” “it was gold. You live for moments like that if you’re doing a piece, good or bad.”

An unsentimental chronicler of “moments like that” who, during more than a half-century at the pinnacle of American letters, examined culture and consciousness with a brittle awareness of disorder before turning her lens on herself in books that plumbed the depths of personal tragedies, Didion died Thursday at her home in New York from complications of Parkinson’s disease, according to her publisher, Alfred A. Knopf. She was 87.

The author bridged the worlds of Hollywood, journalism and literature in a career that arced most brilliantly in the realms of social criticism and memoir.

Her essays explored an eccentric range of subjects — shopping malls, John Wayne, sojourns in Hawaii and havoc in Haight-Ashbury — in a style that was edgy, restrained and elegant.

Photos from the life of Joan Didion, who chronicled California, politics and sorrow in ‘Slouching Towards Bethlehem’ and ‘Year of Magical Thinking.’

Readers of “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” or “The White Album,” her most acclaimed nonfiction collections, “could well follow one of her paragraphs into hell,” an admiring critic once noted. She deployed trenchant facts like surgical bombs, telling us, for example, that seemingly placid San Bernardino in the mid-1960s was the kind of place where it was “easy to Dial-A-Devotion, but hard to buy a book,” where the future always looks good “because no one remembers the past.”

“Nobody writes better English prose than Joan Didion,” critic John Leonard once wrote. “Try to rearrange one of her sentences, and you’ve realized that the sentence was inevitable, a hologram.”

President Obama called her “one of our sharpest and most respected observers of American politics and culture” when he presented her with the National Humanities Medal in 2012. But some critics wanted more from Didion than cool-eyed observations: They wanted to be told what it all meant. “Didion,” Barbara Grizzuti Harrison wrote in the Nation in 1979, “makes it a point of honor not to struggle for meaning.”

Didion wrote 19 books, including the bestselling novels “Play It as It Lays” and “A Book of Common Prayer.” Her nonfiction includes “Salvador,” “Miami,” “After Henry” and “We Tell Ourselves Stories in Order to Live.”

Two of her last books were her most personal.

“The Year of Magical Thinking” (2005) was written after the unexpected heart attack death of her husband and frequent collaborator, John Gregory Dunne. In a wrenching rumination on grief, she appraised their 40-year partnership and described how losing him unhinged her. She also described a series of grave illnesses that beset their daughter, Quintana, just before he died.

Then Quintana died in August 2005, two months before “Magical Thinking” was published. Didion’s next book, the memoir “Blue Nights” (2011), was an effort to come to terms with her only child’s death and what she saw as her failings as a mother.

“Magical Thinking” won a 2005 National Book Award and was her bestselling work, with more than a million copies sold. She turned it into a play directed by David Hare and starring Vanessa Redgrave as the character named Joan Didion, which ran on Broadway in 2007.

“Magical Thinking” was the most overtly personal of Didion’s books, but in a sense all her journalistic writing was personal. Whether the subject was Nancy Reagan, Eldridge Cleaver, Death Valley or Los Angeles freeways, her sensibility — ironic, yearning and uneasy — guided her grapplings with the outside world. Her pieces exuded what the New York Times Book Review called “her highly vulnerable sense of herself.”

Unlike Norman Mailer, Hunter S. Thompson and other pioneers of literary journalism, Didion did not become a character in her own stories. A pale wisp of a woman (90 pounds on a 5-foot-2-inch frame), with drab hair and wide-set eyes often hidden behind aviator glasses, she was by her own description “shy to the point of aggravation.” She preferred to cultivate sources on the periphery of stories, “picking up vibrations” as she circled toward the center and back out again. But in her search for truth and meaning in a world where, as she frequently declared, the center “does not hold,” she told stories with icy clarity.

“My only advantage as a reporter,” she wrote in “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” “is that I am so physically small, so temperamentally unobtrusive, and so neurotically inarticulate that people tend to forget that my presence runs counter to their best interests. And it always does. That is one last thing to remember: writers are always selling somebody out.”

Didion’s ancestors traveled west with the original Donner-Reed Party in the mid-1800s (but parted company before the others met their doom) and settled in Sacramento, where Didion was born on Dec. 5, 1934. Although she would later strike out for points east and south, she retained her clan’s conservative outlook and reverence for a certain pioneer ethic.

Her father, Frank, was an Air Force officer whose job necessitated frequent moves. With her mother, Eduene, and younger brother, James, who died in 2020, she lived near air bases in Washington, North Carolina and Colorado during World War II.

It was a lonely existence for a sensitive child. When Didion was 5, her mother, a former librarian, gave her a notebook “with the sensible suggestion that I stop whining and learn to amuse myself by writing down my thoughts.” In Colorado, she walked the grounds of a sanitarium near their home, eavesdropped on conversations and wrote them down, “hoarding” and “rearranging” the bits of dialogue to make stories.

By the time she reached her teens, she was copying pages of Hemingway on her typewriter to learn how his sentences worked.

Although she said she had a happy childhood, in scattered bits of writing she offered evidence to the contrary. When she was 8 and experiencing the dislocations of wartime, she started having migraine headaches. When she was 13, she walked into the Pacific Ocean at night with her notebook in hand because she was curious about suicide. She came to no harm, but the migraines afflicted her for the rest of her life.

After the war, she and her family returned to Sacramento, where she attended C.K. McClatchy High School. She described herself as the kind of girl who “spent the entire time cutting class, reading novels and smoking in the parking lot.”

When she was rejected by Stanford University, it came as a disappointment so crushing that she contemplated killing herself with an overdose of pain pills.

Instead, after moping for several months, she enrolled as an English major at UC Berkeley. She studied writing with Mark Schorer, who gave her a B for failing to write the required number of short stories.

In 1956 she entered a writing competition for college seniors and won the top prize — a job writing promotional copy at Vogue magazine in New York. Fashion wasn’t a personal priority — she wore tennis shoes to the office and sometimes came in with her hair still wet. Under the tutelage of a demanding editor, she learned to compress her writing by producing eight-line photo captions. “Everything had to work, every word, every comma,” Didion told Paris Review in 2006.

She found New York intoxicating. “Just around every corner lay something curious and interesting, something I had never before seen or done or known about,” she wrote years later.

Yet she missed the Sacramento Valley — its heat, rivers and comforting insularity. Homesickness drove her to write her first novel, “Run River” (1963), which was set among Sacramento’s landed gentry in the 1940s and ‘50s. Like much of her writing, it portrays a world faltering on the brink of incomprehensible change. A marriage ends, a way of life collapses; murder and suicide are the ways out.

With one book to her credit, Didion quit her full-time job at Vogue and freelanced as its movie critic. Her career as a film reviewer ended after she turned in a sardonic review of ”The Sound of Music,” the sentimental 1965 blockbuster about the Von Trapp family and their escape from Nazi-dominated Austria. Didion abhorred its sanitized, upbeat view of one of history’s darkest chapters. “Just whistle a happy tune,” she wrote, “and leave the Anschluss behind.”

By then New York’s charms and Didion herself were wearing thin. She avoided places in the city she once had enjoyed, hurt people she cared about and was constantly in tears. “I cried until I was not even aware when I was crying and when I was not, cried in elevators and in taxis and in Chinese laundries.”

Her doctor gave her the name of a psychiatrist, but she did not go to see him. “Instead,” she wrote, “I got married, which as it turned out was a very good thing to do.” Dunne, a Time magazine staffer she had met on a blind date and married in 1964, helped her through the muddle.

They moved to California, intending to stay six months. It turned into 24 years.

They earned only $7,000 from freelance assignments in their first year in Los Angeles, but work grew steadily, particularly for Didion. From 1965 to 1967 she wrote essays for Holiday, the Saturday Evening Post, the New York Times Magazine and American Scholar, producing most of the pieces that would be collected in “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” published in 1968. She dedicated the book to their daughter, Quintana, whom she and Dunne adopted as an infant in 1966, some time after Didion had suffered a traumatic miscarriage.

During this prolific period, Didion was experiencing depression, the signs of which included “an attack of vertigo, nausea, and a feeling that she was going to pass out,” according to a psychiatric evaluation conducted at St. John’s Hospital in Santa Monica in June 1968. As she later observed in “The White Album,” the attack “does not now seem to me an inappropriate response to the summer of 1968,” a convulsive time of anti-Vietnam War protests and the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy.

That summer was also a difficult time for her marriage. Dunne, suffering a severe case of writer’s block, had taken to roaming California highways in his car. One day he told Didion he was going to buy a loaf of bread and did — “457 miles away at a Safeway in San Francisco,” Michiko Kakutani wrote in a 1979 New York Times profile of Didion. He spent much of the next 18 months living in Las Vegas, which led several years later to a book (“Vegas: A Memoir of a Dark Season”) but did little for his relationship. “We are here on this island in the middle of the Pacific in lieu of filing for divorce,” Didion wrote from the Royal Hawaiian hotel in Honolulu in 1969.

She wrote the title essay of “Slouching” in 1967. Borrowing from W.B. Yeats’ bleak poem “The Second Coming,” she begins with the observation that the “center is not holding” in a culture awash in bankruptcies, evictions, runaway children, absent parents. For a closer look at the chaos, she headed for San Francisco, “where the social hemorrhaging was showing up” and the missing children had surfaced as hippies.

The essay proceeds in fragments, held together by half a dozen aimless characters who cannot implement their visions, much less keep a job; who rely on drugs to attain wisdom that remains elusive; who fail their children and who are, tragically, too immature to know it. Exhibits A and B are Max, a 3-year-old who “does not yet talk,” and Susan, the 5-year-old who tells Didion she is in “High Kindergarten,” who regularly gets stoned on acid supplied by her mother.

“Slouching” won major kudos, called a “rich display of some of the best prose written today in this country” by the New York Times. It established Didion as the preeminent interpreter of California, a place in which, she wrote, “a boom mentality and sense of Chekhovian loss meet in uneasy suspension; in which the mind is troubled by some buried but ineradicable suspicion that things had better work here, because here, beneath that immense bleached sky, is where we run out of continent.”

That Chekhovian sense of loss pervades her fiction. In her 1970 “Play It As It Lays” it is embodied by the central character, Maria Wyeth, an out-of-work actress with a brain-damaged daughter in an institution and a failed marriage to a Hollywood director. She wanders Southern California freeways in a Corvette searching for spiritual cohesion, her emptiness so vast that she puts 7,000 miles on the car in one month. Her words in the book’s famous opening lines reflect a resignation to a life absent meaning: “What makes Iago evil? some people ask. I never ask.”

All Didion’s heroines are the walking wounded, estranged from their own emotions and from those they profess to love. In “A Book of Common Prayer” (1977), which some critics consider her finest novel, protagonist Charlotte Douglas leaves a comfortable life in San Francisco for the imaginary republic of Boca Grande, hoping to reconnect with a daughter who dropped out of college to become a revolutionary in the mode of Patty Hearst. In “Democracy” (1984), Inez Victor also has lost a daughter — to heroin addiction — as well as a sister, who is killed by their father. In “The Last Thing He Wanted” (1996), Elena McMahon has lost her mother, left her husband, alienated her daughter and has cancer.

Didion’s nonfiction was no more consoling. “The White Album,” a collection of 20 essays from Life, Esquire, the Saturday Evening Post, the New York Times and the New York Review of Books, took its title from the 1968 Beatles album with the blank white cover.

The title essay is a jittery embroidery of flashbacks — of strangers who wandered into her house in Hollywood, of a recording session with the Doors at which no music was recorded, of encounters with Huey Newton, Cleaver and Manson family member Linda Kasabian, who wore a dress for trial that had been selected by Didion. A long excerpt from the author’s 1968 psychiatric report serves as a metaphor for a malfunctioning society.

The collection ends somberly with “Quiet Days in Malibu,” in which she writes of a 1978 fire that destroyed a greenhouse full of orchids where she often sought refuge. It scorched 25,000 acres from the San Fernando Valley to the coast and narrowly missed the ocean-facing home where Didion and her family lived for several years, before moving to Brentwood.

What these events mean goes unsaid. (“I don’t like things that are stated openly,” Didion once remarked.) But she leaves a clear impression that an era was closing and Malibu was her Eden no more. “The fire had come to within 125 feet of the property, then stopped or turned or been beaten back, it was hard to tell which. In any case,” she wrote, “it was no longer our house.”

In the 1980s, Didion’s gaze turned outside the United States. The novel “Democracy” was set in Central America, while “Miami” examined the Cuban influx in the American city closest to that island republic.

Her other nonfiction book from that decade was “Salvador,” based on a two-week stay in war-torn El Salvador in 1982. A slim but moving volume that began as an article for the New York Review of Books, it describes visits to body dumps, civilians being herded away at gunpoint by soldiers and discomfiting conversations with American diplomats, missionaries and Salvadorans of varying ranks.

In 1988 she began to write overtly about the American electoral process after months of gentle persuasion by Robert Silvers, co-editor of the New York Review of Books. She collected eight of her essays for that magazine in the book “Political Fictions” (2001), which skewers figures on the left and on the right.

Discussing the intellectual makeup of former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, she said his was “not a mind that could be productively engaged on its own terms.” Reviewing books by Watergate reporter Bob Woodward, she said “these are books in which measurable cerebral activity is virtually absent.” Of Bill Clinton she wrote, “No one who ever passed through an American public high school could have watched William Jefferson Clinton running for office in 1992 and failed to recognize the familiar predatory sexuality of the provincial adolescent.”

The book earned mostly flattering reviews as an incisive critique of a system she perceived as run by and for insiders — the candidates, the operatives, the media. It was published one week after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. Touring the country to promote the book gave her an opportunity to monitor the tensions arising in the national dialogue on the calamitous event and resulted in a lecture she gave a year later at the New York Public Library.

The lecture was published in 2003 as “Fixed Ideas, America Since 9.11.” Only 56 pages long, the slim volume offers her impressionistic observations about the national pieties that she says the Bush administration used to justify not only war in Iraq but its policies involving school prayer and environmental deregulation. Booklist called it “an essential work of clarity in a time of obfuscation.”

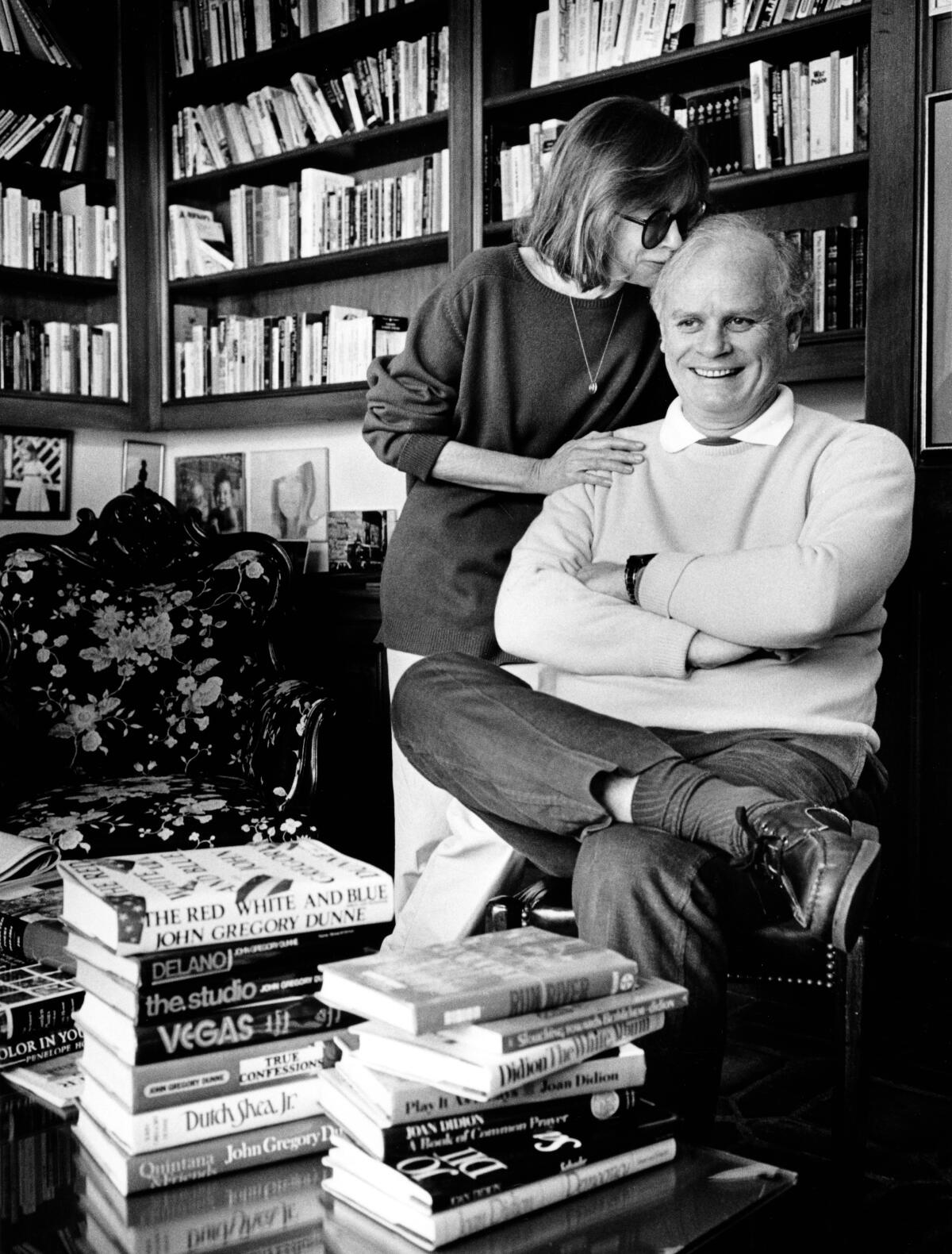

Dunne had been her first editor on all the books she wrote after they married. They also collaborated on several screenplays, including “The Panic in Needle Park” (1971) with Al Pacino; the 1976 remake of “A Star Is Born” with Barbra Streisand; the adaptations of “Play It as It Lays” (1972) and his novel “True Confessions” (1981); and “Up Close and Personal” (1996), which starred Robert Redford and Michelle Pfeiffer. Didion and Dunne were celebrities in their own right — “the Lunts of the Los Angeles literary scene,” according to writer John Lahr — who attended A-list Hollywood parties and were regulars at the town’s toniest restaurants.

They traveled together as journalists and finished each other’s sentences, a habit that writer Susan Braudy said made their conversation sound like “a two-person monologue.” They were, in Didion’s words, “terrifically, terribly dependent on one another.”

After two decades in California, they moved back to New York in 1988.

They were well settled into life there when, in late 2003, Quintana was hit by a series of illnesses: flu symptoms that ballooned into pneumonia and septic shock and finally landed her in a coma. On the evening of Dec. 30, after visiting her in the hospital, Didion and Dunne were sitting down for a late supper in their apartment off Madison Avenue. Didion was tossing a salad when suddenly Dunne “slumped motionless” in his seat and fell to the floor. “John was talking, then he wasn’t,” Didion would later note.

At first she thought he was playing a bad joke, but he was not. One month shy of their 40th wedding anniversary, he was dead from a massive coronary. He was 71.

“Life changes fast

Life changes in the instant.

You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends.”

She set down those words a few days later, willing herself to write her way to understanding an unfathomable loss. Written in her trademark style — terse, elliptical, clinically detailed — “The Year of Magical Thinking” chronicled the year after Dunne’s death, when she went a little crazy. Quintana was in and out of consciousness and Didion had to tell her three times that her father was dead. She would not erase her husband’s voice from the answering machine and refused to give away his shoes, reasoning that he would need them when he was able to “come back.”

While her previous book, “Where I Was From” (2003), had been part memoir, combining analysis of the California dream with recollections of Sacramento and the deaths of her parents, “Magical Thinking” was wholly personal, and piercingly raw. The Times of London called it “a masterpiece of restraint and perception.” Leonard wrote: “I can’t imagine dying without this book.”

It sold 200,000 copies in its first two months — more than any other Didion work in hardcover — topped bestseller lists for months and was a Pulitzer finalist. The stage adaptation earned mixed reviews (“arresting yet ultimately frustrating,” wrote Ben Brantley in the New York Times) and closed after 144 performances.

Didion was stunned by the book’s success, but the achievement was bittersweet.

Quintana had recovered sufficiently to attend her father’s funeral, which was finally held in March 2004. But a few days later she collapsed from a cerebral hemorrhage. Other complications followed, and she died on Aug. 26, 2005, at 39. In October, the month “Magical Thinking” was published, Didion placed her daughter’s ashes next to those of her husband.

Five years later Didion began to write “Blue Nights,” named for the lingering twilights that precede the summer solstice and a dark period in the author’s life when “I found my mind turning increasingly to illness, to the end of promise, the dwindling of the days, the inevitability of the fading, the dying of the brightness.”

“Blue Nights” was a dual portrait — of Quintana as a troubled child who once called Camarillo State Hospital to find out what she should do if she went crazy, and of Didion as a failed parent, too self-absorbed to recognize her daughter’s emotional difficulties. Published when Didion was 75, it also lays bare the author’s struggles with getting older.

“During the blue nights you think the end of day will never come. As the blue nights draw to a close (and they will, and they do) you experience an actual chill, an apprehension of illness, at the moment you first notice: the blue light is going, the days are already shortening, the summer is gone.... Blue nights are the opposite of the dying of the brightness, but they are also its warning.”

Woo is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.