Editorial: Some schools are overdoing it with frightening active-shooter drills

- Share via

A school safety drill in San Gabriel reached an extreme last week when, according to parents and students, the principal of the elementary school walked around, using her fingers to mime holding and shooting a gun. She reportedly pointed at individual students saying, “Boom. You’re dead.”

The principal, Nina Denson, has been pulled from her duties while the school district investigates the complaints from parents. If the allegations are true, it would appear that Denson was acting out of a horribly mistaken belief that traumatizing children is the way to get them to take the drill seriously.

A sweeping new Justice Department report that highlights the failures of Uvalde first responders is also a primer on effective approaches to mass violence.

Though the circumstances in this case sound as though they crossed a line, it’s worth considering whether schools are overdoing disaster drills, especially ones involving gun violence. Drills are certainly needed for some situations — “evacuation drills” for fires and “drop-cover-hold” for earthquakes. There also are shelter-in-place drills when circumstances off campus call for students to remain in school. “Reverse evacuation drills” have students return to the school building when there’s a dangerous situation outside. Then there are the lockdowns or active-shooter drills.

California schools require disaster and and other “multihazard” drills. But school officials should give more thought to how many drills are conducted, and how to reduce the fright level, especially for young children, because researchers say there’s no objective evidence that they increase preparedness for a dangerous attack.

Training teachers to recognize the sound of gunfire but not the distress signs of children spiraling toward violence is a bleak, wasteful affair.

Most schools don’t do anything like what allegedly happened in San Gabriel. Then again, some drills have been worse. Without any warning that a drill was at hand, one preschool blasted the sound of gunfire through its loudspeakers. Some Missouri schools had students paint what looked like bleeding bullet holes on themselves. In 2020, San Marino High School was planning a drill in which police would fire blanks for 11 minutes so that students would understand the sound of gunfire. The high school backed off after the American Civil Liberties Union registered its concerns.

There have been multiple calls to do away with active shooter drills, or at least the most realistic ones. Though the headlines can be terrifying at times, the world is not as frightening as those drills would have children believe. The gun-violence prevention organization Everytown for Gun Safety recommends against them, noting that 0.2% of gun deaths occur at school, while the drills were practiced at 95% of schools in 2015-16. Those are the most recent numbers available but there’s no reason to think the use of the drills has waned. Drills can even be counter-productive, the organization says, because the shooters tend to be current and former students who learn how the school will react to a shooting and possibly how to circumvent protections.

This country is exactly the place for hateful, murderous, suicidal gun violence, because this is the place for millions upon millions of guns and the bizarre American delusion that the more of them we have, the safer and freer we are.

In 2023, 57 people were killed in school shootings, compared with drastically higher rates of suicide and off-campus homicide. If we want to save more children’s lives from gun violence, we should work harder to prevent teen suicide, intercede more quickly when youngsters show signs of emotional distress and regulate access to guns.

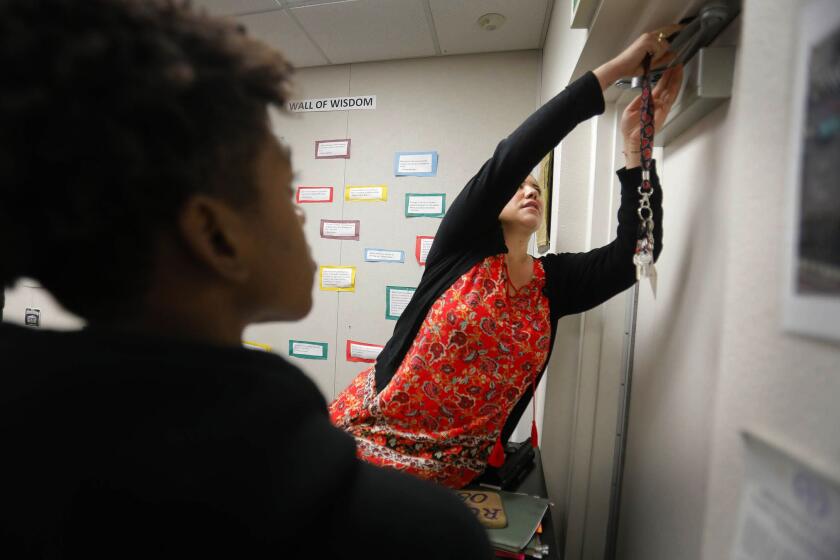

It’s understandable that some parents and schools want students to know how to protect themselves in dangerous situations. States should provide some strong guidelines about how to conduct drills, keeping in mind that children’s mental health is as important as their physical health. In neighborhoods where students hear gunfire and worry for their safety, experts say, the drills can be especially frightening. There’s no reason young children need to know a drill is about an active shooter, especially given how small the chances are that such a thing would occur. They can give their drills nicknames or, as some schools do, call a lockdown something like “dark and quiet,” which describes what to do without inducing nightmares.

School shootings are awful to contemplate. But the horror should not lead us to believe that they are more common than the data tell us, or that schools can somehow drill their way out of it.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.