Opinion: I recently took part in my first ‘active killer’ school drill. It was as terrifying as it was misguided

- Share via

One day last winter, before Florida passed a law allowing teachers to carry guns in schools, my high school students were settling into the languid routines of study hall. Some asked for library passes. Others sprawled over laptops and textbooks or pulled copies of “Monster” by Walter Dean Myers from my bookcase. Despite being told to put their electronics away, earphone cords hung like IV lines, tethering minds to phones.

Within minutes, an administrator stood before the class and asked: “So, when the shooter comes, where are you going to hide?” After a stunned pause, students pointed to a corner table where they’d crouched during active shooter drills. Others pointed to the storage room door. It led to a space crammed with moldering grammar books, used notebooks and student posters diagramming the argumentative essay — the legacy of the room’s previous occupants in our Broward County school.

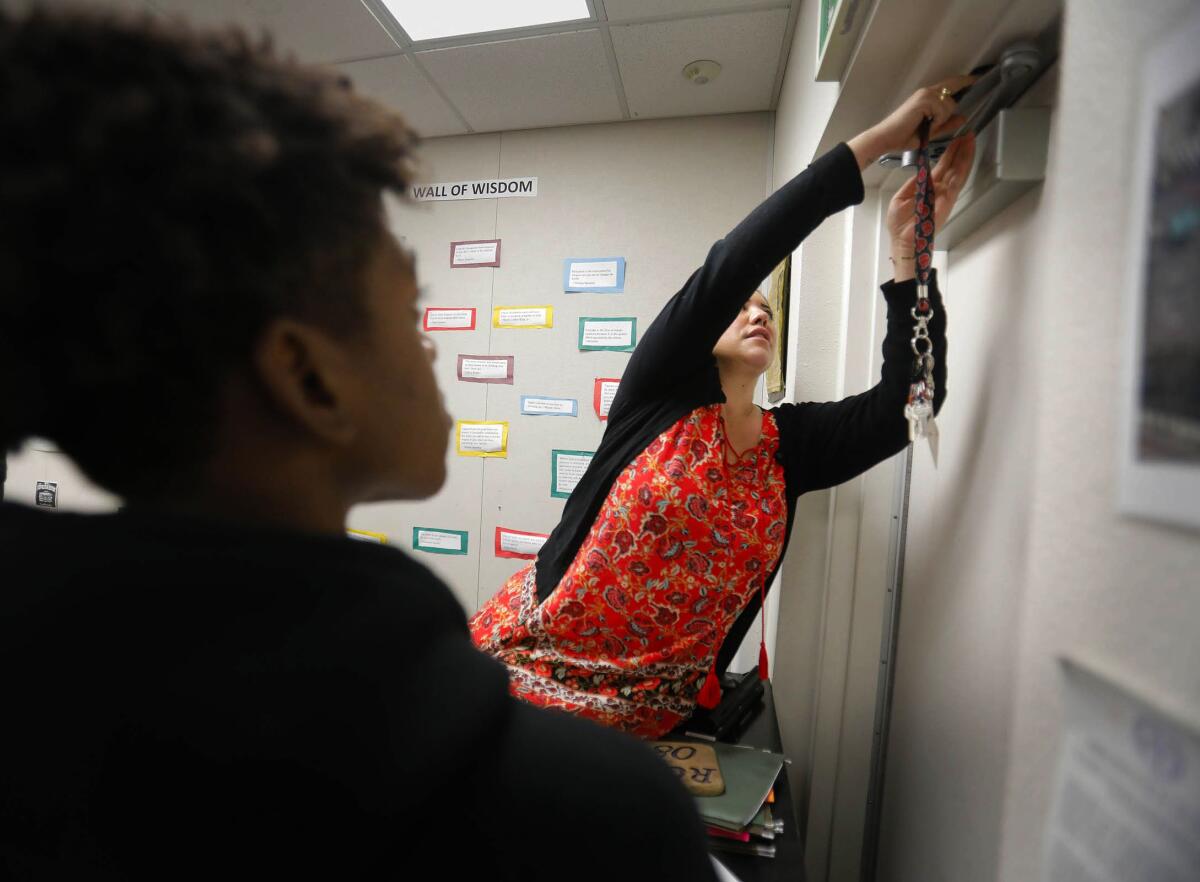

The administrator tore off some blue adhesive tape and marked the wooden door of the storage room with a large X. She placed another X on the wall just above the wobbly table. The tape marked our hiding spots — dimly configured areas where the shooter couldn’t see us from the door window. Gun violence was now part of my wall decor, a detail in a haphazard strategy to train teachers — civilians with education degrees — to ward off shooters and save students’ lives.

“Excuse me,” said one student who spent study hall tweaking $70 wigs she makes and sells. “Won’t the shooter know there are people on the other side of that big old X?”

“No,” she was told. “He’s looking for live bodies. When he doesn’t see any, he’ll move on.” Live bodies. I felt a collective shudder in the room.

For weeks, the blue Xs hovered like crosses, reminding me of the possibility of mass death in my English classroom. Eventually, they were replaced with a blue sticker showing three potato people nestled under a ceiling, a “safe space” signpost.

A few weeks later, sheriff’s deputies and school district officers converged at my school for a teacher-only training. It was our first “active killer” drill. An officer flecked his opening talk with jokes meant to calm an audience for whom gun violence still existed in a parallel world. He proceeded to lay out the scenario of our survival or death in a PowerPoint presentation titled “Active Killer Response Recommendations.” Some of the “lesson objectives” included “Utilizing Students in Target Hardening” and “Teacher Accountability.”

Oh, and he wanted to know: Had we ever heard the sound of gunfire? I had not, and I was not alone. The blanks went off without warning. We needed to know this sound, he said, to be able to discern it from all else in a world of noise. My breath caught as the force of the sound of the shot tore through the room and ricocheted in our bones. The gun and non-gun worlds drew closer together.

Next, we listened to an excerpt from a dispatch call from the 2012 Sandy Hook shooting. We heard a woman pivot between a vice principal who’d been shot and lay bleeding on the floor and the entrance of the room they were in. Her voice was a strained whisper. It carried the even inflections of trauma. She reported the shooter was “right outside the door.”

By the end of the recording, a sense of panic and nausea welled up in me. A teacher a few rows ahead of me shook with sobbing. The officer walked over and embraced her. He proceeded with the rest of the PowerPoint: “Active Killers generally do not expect to escape or survive. Active Killers are looking for victims — not a friend, not a solution and not an agreement.”

After we were dispatched to various classrooms for the actual drill, we asked unimaginable questions: Which drywall corner was best to hide in? Can a semiautomatic weapon shoot open a steel door? If the shooter enters the adjoining classroom, can he shoot through this flimsy partition wall?

Two police officers responded kindly and firmly. Use what you can as a weapon. Someone should stand against the wall by the door to stop the shooter from trying to unlock it once he shoots through the glass window. It’s you against him. He’s armed, and if he gets inside your classroom — you’re done.

One question caused our throats to snag. What about students trapped in the hallway, begging you to open the door? The officers said we might be sacrificing the lives of everyone inside to let one or two kids in with the shooter nearby. One particular student came to mind — she knew all the words to the songs in Disney’s “Mulan” and once chided me for assuming every student in class had a mother. Near the beginning of the year, the principal had told us, “We are their mothers and fathers.” In the brief calm of this nightmare reflection, I opened the door for her. I could hear my colleagues’ muted gasps. Some had their eyes closed. They too were opening hypothetical doors.

Within seconds, the lights were out, and the drill was on. Officers ran around outside shouting, banging on doors and shooting. In my drill classroom, the teachers ran to the same corner, lightly trampling each other before crouching. Then we were completely still. Survival, even of a simulated attack, felt alienating and brutish.

When the drill was over, I returned to my classroom and chilling news: Two Parkland survivors had committed suicide. That high school is mere miles from mine. Their families attributed the deaths to survivor’s guilt. Later, I learned one of my students had danced in a performance at the boy’s funeral.

Dancing as a salve for trauma made sense to me. But a “professional development day” that herds us around to the sound of gunfire, yet fails to train anyone in the distress signs of children spiraling toward violence is a bleak, wasteful affair.

Yet my training was comparatively mild.

Teachers in Indiana reported being shot with pellet guns at close range as part of a drill, prompting a state campaign to prohibit such measures. In Iowa, teachers reported suffering “secondary trauma” as a result of their training. And research has shown that active shooter training makes students more afraid that a shooting might occur at school.

Despite their reported ubiquity, school shootings are less likely to end the lives of students and teachers than the proverbial lightning strike. Deaths from shootings on campus are extremely rare. About 55 million students are enrolled in elementary and secondary schools in the U.S. — and over the last 25 years, an average of 10 students a year have been killed by gun violence at schools, according to Northeastern University research.

While teachers and administrators need to know how to respond to a gunfire crisis, the rise of active shooter training feels like an extreme and misguided approach.

We are now well into another fall term, and we will surely have more sobering lessons in survival. But a new school year also brings a sense of renewal and hope. Despite the encroaching shadow of guns, a restorative normalcy still prevails in school just as it does in life, even when we are taught that extinction may come at any point during the lesson.

Tal Abbady teaches high school English in Broward County, Fla.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.