Opinion: A death row inmate has been waiting 18 months for DNA test results that could prove his innocence

- Share via

All too often the road to redressing an injustice is hard to navigate, which is frustrating enough. But when a pathway is clear, and progress is still not made, the underlying injustice gets compounded.

That’s the problem Kevin Cooper faces.

Cooper was sentenced to death in 1985 after he was convicted of hacking to death four people and severely wounding a fifth person in Chino Hills two years earlier. It was not an open-and-shut case, and Cooper then, as now, proclaimed his innocence.

He’s not alone in believing he’s innocent or that at the least he did not receive a fair trial.

This year, states have executed 19 people despite lingering questions over the guilt of several of them. Why do we cling to this system?

The case against Cooper is, to put it mildly, unpersuasive, and the handling of the investigation should give pause to anyone. Evidence was planted; other evidence was not shared with his lawyers in violation of court rules; clear indications of the possible guilt of another man were ignored; leads went unfollowed — even a bloody pair of overalls linked to the other suspect was tossed out by police.

Talk about reasonable doubt.

The case, like most capital crime cases, has generated a long series of appeals, most of them unsuccessful, though in one dissenting opinion a federal appellate judge warned that “California may be about to execute an innocent man.” Fortunately, that execution was delayed, but Cooper remains on death row.

DNA testing not available at the time of the trial could determine whether items tied to the crime had been touched or used by Cooper, and Gov. Jerry Brown finally moved in the last days of his administration to address the issue. On Christmas Eve, 2018, he ordered limited DNA tests of some of the physical evidence; two months later, newly installed Gov. Gavin Newsom expanded the scope of the tests to include more items of evidence.

Since then, the public has heard virtually nothing about how the tests are proceeding.

Note that 18 months have passed.

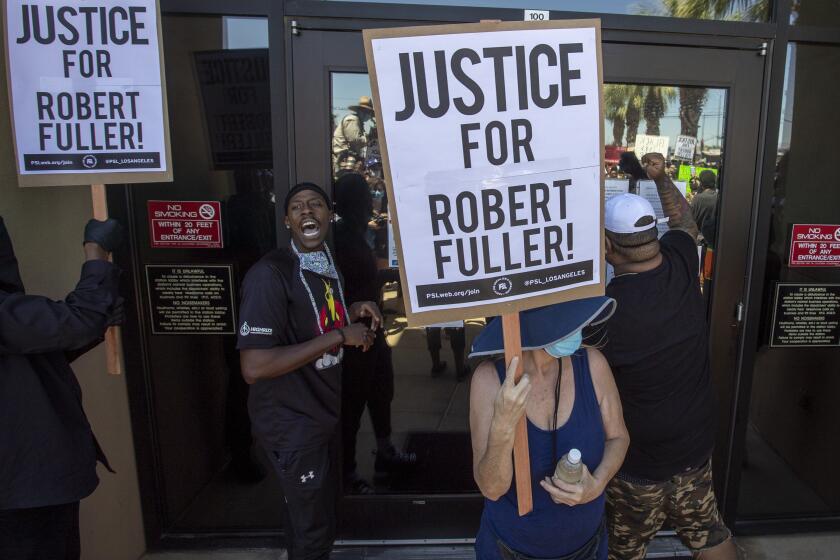

Even if the hangings of Black men in Palmdale and Victorville look at first glance like suicides, there had better be in-depth investigations.

Newsom’s office explained that the testing is “ongoing” and that “the Special Master is working closely with the parties and supervising this process to ensure that it proceeds in a fair, thorough, and appropriate fashion.” The special master himself — former Judge Daniel Pratt — didn’t respond to an interview request, and Cooper’s lawyer, Norman C. Hile, has not responded to recent requests for an update on where the tests stand.

I have no set opinion on whether Cooper is factually innocent of the murders for which he has been convicted, but it’s clear that the evidence against him does not prove his guilt. The best dissection of that evidence — and the behavior of the criminal justice system in San Bernardino County at the time — comes from Judge William A. Fletcher, who wrote the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals dissent I mentioned above and reprised it in a 2012 speech on the death penalty.

The murders themselves were brutally heinous. Doug and Peggy Ryen; their 10-year-old daughter, Jessica; and sleepover guest Christopher Hughes were stabbed at least 143 times with an ice pick, an ax and a knife, and 8-year-old Joshua Ryen was lucky to survive a slashed throat. He initially told a social worker at the hospital that he had seen three or four white or Latino men enter the house, but later — after multiple visits by a sheriff’s investigator — said he had seen only the shadow of one man.

That just happened to align with the theory advanced by San Bernardino County Sheriff’s investigators that the crime had been perpetrated by a single person: Cooper, a Black man and convicted burglar, who at the time of the murders was holed up in an adjoining vacant house after escaping from a nearby state prison.

Five people slashed and hacked 143 times by one person wielding an ice pick, an ax and a knife?

As the surviving victim’s grandmother told CBS in a “48 Hours” news program that aired in March, “I still can’t believe that one person … could do all that to my family. There’s five of them, and I just know that they didn’t stand in line saying, ‘I’m next.’”

Yet that’s what the investigators and prosecutor persuaded a jury had happened.

This is the compounded injustice. The fresh round of DNA tests could rule Cooper out as the killer, or potentially undercut his argument that he’s innocent. Yet that process has dragged on, without a public explanation, for a year and a half.

If the tests exonerate Cooper, as he and his advocates believe they will, the longer this process drags out, the worse the injustice becomes.

And the people of California — in whose name Cooper has been imprisoned — deserve to know whether an innocent man has spent most of his adult life in prison, while the guilty were never pursued.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.