Must Reads: ‘They framed me’: On death row for decades, Kevin Cooper pushes for new DNA tests in Chino Hills murders

- Share via

In a tiny visitors cell at San Quentin State Prison, Kevin Cooper makes a pitch for his innocence — an argument that, after three decades on death row and endless legal battles, suddenly has new life.

In 1983, he was a convicted burglar and prison escapee accused of hacking two adults and two children to death in San Bernardino County. He was convicted and sentenced to death. His supporters claim in a clemency petition that he was framed by sheriff’s deputies, undone by poor defense lawyers and railroaded by racism.

“They framed me because I was framable,” says Cooper, now 60, his graying hair falling from cornrows to the nape of his neck. With countless letters to reporters and media interviews over the years, he has skillfully attracted public attention to a case that prosecutors and the courts have long considered closed.

Doubts about Cooper’s conviction have grown since the trial, even as state and federal courts have repeatedly upheld the verdict. At least three jurors have said they are no longer sure he is the killer. Lillian Shaffer, the sister of one victim, now says “it seems impossible that he could have done all of that destruction by himself.” A federal appellate judge, in a vigorous 2009 dissent, warned that the state might have the wrong man.

In May, Sens. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) and Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) called for fresh DNA testing after a New York Times column called the case against Cooper “outrageous.” Earlier this year, four California law school deans called on Gov. Jerry Brown to open an independent investigation, declaring that Cooper’s claim of innocence “has never been fully and fairly evaluated.”

With Cooper’s judicial appeals exhausted, his fate lies principally with the governor, whose legal staff has been digging deeply into Cooper’s 2016 clemency petition and the case record, as well as discussing the situation with the current prosecution and defense teams.

In a July 3 letter to the defense, Brown’s legal affairs secretary, Peter A. Krause, left the door open to further DNA testing while pressing defense attorney Norman Hile, in nearly six single-spaced pages, to justify the arguments he is making.

“Each time, additional forensic testing has been performed in this case…the test results only further established Mr. Cooper’s guilt,” Krause wrote, asking Hile to answer by Aug. 17.

Hile promised to reply to Krause’s queries.

“It’s about time they acted,” Hile said in an interview. “We’re glad that they’re considering the DNA testing.”

Michael Ramos, the San Bernardino County district attorney, strongly objects to further testing, arguing in a May statement addressing renewed interest in the case that the lone survivor and the relatives of the victims have suffered “repeated and false claims from Cooper and his propaganda machine designed to undermine public confidence in the just verdict.”

Brown, who has issued far more pardons than any modern predecessor in California, must confront two central questions: How sure does the state have to be to put a man to death? How sure can it be that Kevin Cooper committed this crime?

Figuring out what happened 35 years ago is complicated. Memories have faded. Witnesses and investigators have died. This story is the result of a 10-week investigation by 10 reporters with Northwestern University’s Medill Justice Project who interviewed more than three dozen people, reviewed thousands of pages of documents and spent hours with Cooper at San Quentin.

The crime

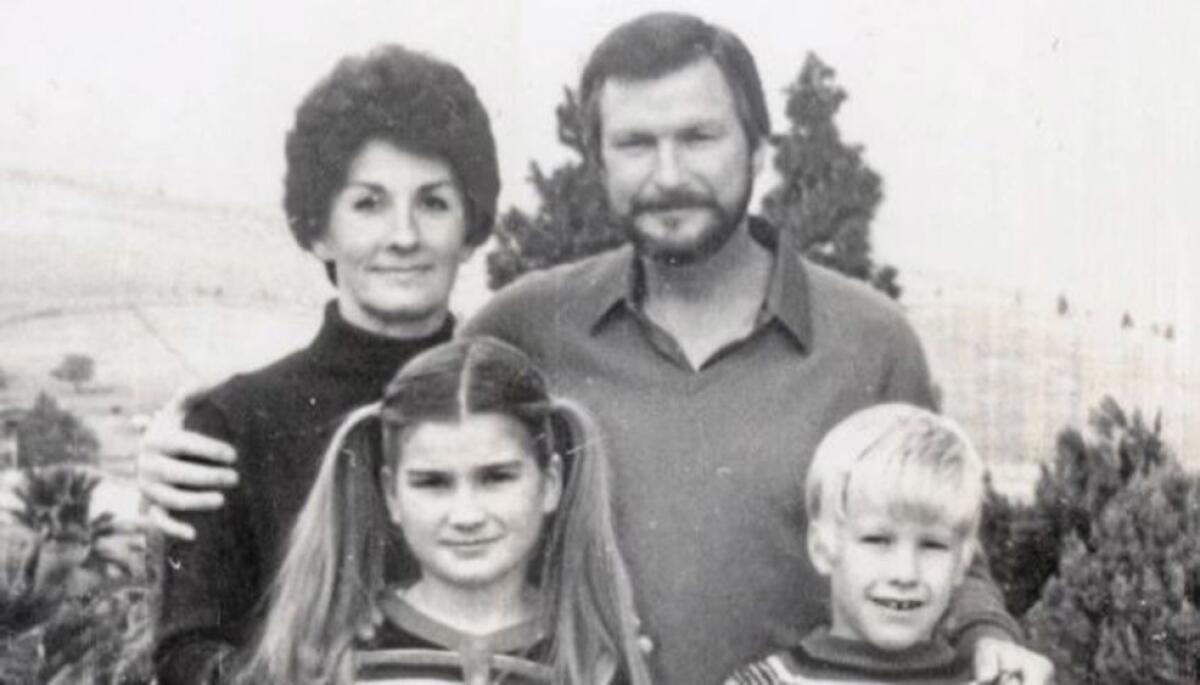

On June 5, 1983, William Hughes peered through a sliding glass door into the master bedroom of the Ryen family’s house in Chino Hills. He spotted the bloodied body of his 11-year-old son Christopher, who had spent the night with the family. Nearby were Peggy and Doug Ryen, hacked and slashed to death. Eight-year-old Joshua Ryen lay on the floor, his throat slit, but alive. Out of sight in the hall was Jessica Ryen, 10, no longer breathing.

Three days earlier, Kevin Cooper, then 25, had escaped from the California Institution for Men in Chino, about four miles away.

He broke into an empty house on English Place, about 150 steps across a grassy field from the Ryen home. He spent two nights there, planning his next move. He called two friends asking for money. They declined. Phone records show that one of the calls was made from the hideout house shortly before the murders.

Cooper would say later that he knew nothing about the killings and was by that time on the road to the Mexican border, about two hours’ drive away. Although police said they found prison-issued tobacco and DNA consistent with Cooper’s in the Ryens’ stolen station wagon, he told the jury he had never been in the car.

San Bernardino County Sheriff's Department detectives soon named Cooper as the primary suspect. By the time Cooper was captured on July 30, rowing away from a dock near Santa Barbara, community sentiment ran strongly in favor of his guilt. Protesters shouted and raised signs. One poster read, “Hang the nigger.”

The verdict

During the trial a year later, prosecutors said a drop of blood taken from the wall of the Ryens’ home was consistent with Cooper’s genetic profile. They pointed to the hand-rolled cigarettes in the station wagon. They produced a blood-stained hatchet found in the weeds near the Ryens’ house and showed the jury a hatchet sheath found in a closet in the house where Cooper had stayed.

Prosecutors said footprints found on a spa cover and a sheet in the Ryens’ house matched one in the hideaway house. The footprints were consistent with Pro Keds Dude tennis shoes issued to California prison inmates. Investigators also shared evidence of what may have been blood on shower walls in the hideout house, suggesting that the killer washed up there before fleeing.

Joshua, the sole survivor, said on a videotape shown to the jury that he saw a single man or a single shadow during the attack. He said the person had a “puff” of hair. In an earlier photo that prosecutors sought to present in court, Cooper wore a dashiki and his hair in an Afro.

The trial lasted four months, stretching into 1985. After deliberating for five days, the jury found Cooper guilty of all four murders and the attempted killing of Joshua. They returned to the jury room and, a few days later, concluded that Cooper should be executed.

Over and over, state and federal courts rejected Cooper’s assertion that he was wrongly convicted. In 1991, the California Supreme Court ruled that it was “utterly unreasonable” to imagine that someone else in the neighborhood where Cooper was hiding committed the murders. The “sheer volume and consistency of the evidence is overwhelming,” the court wrote.

In February 2004, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit stepped in and stopped the clock just three hours and 42 minutes before his scheduled execution. Previous DNA testing had connected Cooper to the crime scene and to a bloody T-shirt found not far away, but the court ordered more tests, on strands of hair found in Jessica Ryen’s left hand and on the shirt, which the prosecution had not introduced at the trial.

The tests on the hair suggested that it came not from the scalp of an attacker, but from the Ryen family or from animals. Cooper’s blood on the shirt tested positive for a preservative used in blood samples, leading his defenders to accuse the government of tampering.

After reviewing the tests and hearing testimony from 42 witnesses, Chief U.S. District Judge Marilyn Huff said in 2005 that the conviction should stand: “There is overwhelming evidence that Petitioner is the person guilty of these murders.”

Cooper appealed again to the 9th Circuit, often considered the most liberal federal appellate court in the country. A three-judge panel affirmed Huff’s decision in 2007.

A majority of the full court declined to reopen the matter in 2009. But one 9th Circuit Judge, William Fletcher, wrote a 100-page dissent, adopted in full by four of his colleagues. He wrote, “The State of California may be about to execute an innocent man.”

Cooper's questions

Cooper says he was convicted in a “bogus-ass trial.” Others share his doubts.

“Too much continues to bother me about the case,” one juror wrote in 2004 in support of Cooper’s clemency petition. Referring to the verdict and death sentence, the juror said, “I now regret that decision.”

Cooper’s current attorneys question the competence of his initial defense team. David Negus, who represented him at the trial, said in a 1996 declaration on Cooper’s behalf that his performance in the case was “negatively affected” by his stress and exhaustion. Negus added that he did not keep up with the daily trial transcript and rejected Cooper’s request to bring on a second lawyer, something he recognized only later was beneficial in complex death penalty cases.

One motion, the lawyer said, was just “thrown together” for lack of time and he did not complete a comprehensive statement on the physical evidence in the case. Interviewed this year by The Medill Justice Project, he said that with more experience he could have done a better job.

A key piece of evidence in the trial was a series of shoe prints at the scene.

Prosecutors told the jury that they matched a model of Keds primarily worn by prison inmates, but former Warden Midge Carroll testified at an appellate hearing that such shoes were widely available. Indeed, the shoes appear in a 1981 Keds catalog.

“I don’t think the investigation was honest,” Carroll says now, asserting that San Bernardino law enforcement officials “have tried to intimidate me throughout the years.”

Then there is the testimony of Joshua Ryen. The jury heard him say that he saw just one man or maybe a shadow in his home. But when first interviewed by social worker Donald Gamundoy, he told a very different story.

Then 8 years old and unable to speak because of a slit throat, he answered questions by pointing to letters, numbers and the words “yes” and “no” on a piece of paper. By pointing, he indicated that three or four men had attacked the family, Gamundoy said.

When Gamundoy asked if the attackers were black, Joshua pointed to “no.” When asked if they were white, he pointed to “yes.” It was more than a year later, when interviewed on camera by the prosecution team, that Joshua said there had been only one attacker.

Gamundoy no longer has his notes, but stands by his recollection. Reviewing the case in 2011, San Diego Superior Court Judge Kenneth K. So suggested Joshua may have been confused because three Hispanic visitors had come to the door earlier in the day looking for work. (Joshua has not spoken publicly about the apparent discrepancy.)

Joshua was not the only person to suggest that three men might have been involved, though. At the Canyon Corral Bar, about two miles from the Ryen house, several witnesses later told investigators that they saw three unfamiliar men the night of the killings. Bar patron Christine Slonaker, a licensed phlebotomist, testified in 2004 that she remembered the night well, “because it isn’t too often you run into people that have blood all over their clothes.”

And then there are the green button and the hatchet sheath that police said they found in the closet of the hideout house. Prosecutors said Cooper left the hatchet sheath and the button there. Yet an initial police report made no mention of the two items.

Cooper’s supporters contend that the case doesn’t add up. If he needed a car to escape, he could have taken the Ryens’ cars without a struggle; they left the keys in both vehicles. Prosecutors said he committed the murders because he needed money, but investigators found dollar bills and coins in plain sight on the kitchen counter.

The most strongly contested pieces of evidence are blood spatters and stains that the prosecutors and numerous judges have cited in upholding the guilty verdict. His defenders argue that tests on certain pieces of evidence have been unreliable and may reveal tampering.

Prosecutors linked Cooper to the crime scene at the Ryen home by pointing to Exhibit A-41, a drop of blood from a wall in a hallway. It contained serological markers matching a person of African descent. The key witness was San Bernardino technician Daniel J. Gregonis, who testified that he made a mistake in his initial identification of A-41 but revised his assessment of the blood type after further testing.

A defense expert, Edward Blake, also conducted tests on A-41 as Cooper’s team prepared for trial. Reviewing the case more than 25 years later, Judge So found it significant that Blake, too, connected the sample to a person of African heritage and ruled out a Caucasian or Hispanic person.

But Fletcher, in his 9th Circuit court dissent, cited the testimony as evidence that the testing happened under “suspicious circumstances.”

Old evidence, new demands

Since 1985, the year of Cooper’s conviction, DNA tests have become more sophisticated. Cooper’s legal team has consistently pursued more advanced DNA tests, but they have not always worked in his favor.

When the A-41 spatter was tested again in 2001, Judge So wrote, technicians found the likelihood of a match occurring randomly among African Americans to be 1 in 310 billion. A test on the tan T-shirt found near the Canyon Corral Bar matched Cooper, as well as at least one of the victims, he noted.

Paul Ingels, a private investigator who started working with Cooper’s defense team in the 1990s, said those tests led him to conclude that the evidence against his client was “overwhelming.”

Cooper’s team more recently argued, however, that the blood was planted. They point to tests that suggest the blood on the T-shirt contained the preservative EDTA, which is added to blood samples collected in vials. That could indicate the blood came from a vial of Cooper’s blood collected by investigators. In addition, they note, traces of other people’s DNA were detected in the vial of Cooper’s blood.

“This finding,” his attorneys wrote in the 2016 clemency petition, “suggests that blood was added to the vial to replace blood used for planting and throws into question all of the evidence the jury heard at Mr. Cooper’s trial.”

“The observed facts are consistent with a concerted effort to tamper with evidence in a manner that would incriminate Kevin Cooper,” Janine Arvizu, a chemist who worked on Cooper’s behalf, said in an interview.

Dist. Atty. Dennis Kottmeier, who prosecuted Cooper, said people at the crime scene made "some minor mistakes,” including failing to compare blood found in the Ryens’ kitchen with Cooper’s blood. But he said the mistakes amounted to “nothing that would lead to” acquittal.

David Stockwell, a deputy sheriff, acknowledged that it is possible, as Cooper’s attorneys contend, that as many as 70 people were allowed to enter the crime scene in the first 24 hours. But he disputes any suggestion that police tampered with the evidence in the Ryen home, the hideout home or the Ryen vehicle.

Ingels, the defense investigator, contends that the sheer number of investigators at the scene makes it less likely that they engaged in an effort to frame Cooper.

“The conspiracy to plant all of that evidence would’ve been very, very difficult,” he said. “I mean, you’d have to have a lot of corrupt people running around.”

Cooper’s attorneys, however, argue that corruption in the San Bernardino sheriff’s department “went right to the top.” As they noted in their 2016 clemency petition, Sheriff Floyd Tidwell, who headed the crime scene investigation, pleaded guilty more than two decades later, in May 2004, to stealing more than 500 guns from county evidence rooms. They said William Baird, the head of the department’s crime lab who testified about shoe print evidence, was fired a year after Cooper’s conviction for stealing heroin from an evidence locker.

Five days after the murders, a woman named Diana Roper had turned in a pair of coveralls to the Sheriff’s Department after hearing about the killings. The clothing belonged to her then-boyfriend Lee Furrow, a previously convicted murderer. She said the stains on the coveralls were blood and that he changed out of them the night of the murders.

“I told the deputy the facts about how I found the coveralls and that Lee Furrow may be the murderer,” Roper wrote in a 1998 statement to the court. Deputy Frederick Eckley took her report and accepted the overalls. A few days later, the San Bernardino Sheriff’s Department discarded the coveralls without testing them.

Kottmeier said in an interview that the coveralls were discarded because they had “no connection to the crime scene,” about 50 miles from Roper’s house. Furrow could not be reached for comment, but in an interview with CBS’ “48 Hours,” he said he had “nothing to do with any of this.” He repeated that denial to The New York Times earlier this year. Roper has since died.

Who is Kevin Cooper?

“Kevin wasn’t super nice, but he wasn’t a killer,” Midge Carroll, the warden during Cooper’s brief time at the California Institution for Men, said in a recent interview.

The prison’s recreation supervisor, Skip Arjo, was more skeptical.

Cooper was “like a chameleon,” he says. “He could turn the charm on, and he could turn it off.”

Cooper and his legal team are asking Brown to pursue more advanced forensic testing, grant a new trial or even commute his death sentence, something that his predecessor, Republican Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, twice declined to do.

“We need to make sure, where there is a case like Kevin Cooper’s, with serious questions, that we don’t execute and find out they are innocent after,” said Norman Hile, his attorney. “That’s all we are asking the governor to do.”

In questions sent to Hile last week , Brown’s legal affairs secretary asked how any new DNA tests would be carried out and what Hile expects them to show. He also asked Hile to explain arguments about San Bernardino County authorities’ behavior that are “apparently inconsistent,” including why they would issue an all-points bulletin for three white or Hispanic suspects at the same time they were allegedly planting evidence against Cooper. He offered no timetable for Brown’s decision in the case.

A central remaining question for Brown is Cooper’s credibility. Cooper readily admits to a series of burglaries that put him behind bars, to adopting false identities that confused law enforcement and to escaping several times from prison.

Cooper’s past also includes another serious criminal charge, filed in Pennsylvania.

A teenage girl testified during the penalty phase of Cooper’s trial that, less than a year before the Ryen killings, she dropped by a friend’s house in Pittsburgh and was attacked by a stranger who answered the door. The stranger, who appeared to be in the midst of burglarizing the home, hit her with a camera and dragged her into her car. She said he told her to put her head in his lap facing forward, where she was unable to see his face.

He then drove her to a secluded area of a nearby park. She testified that he forced her to the ground, face-down, a screwdriver against her neck, raped her and drove away.

Police found Cooper’s palm print on the gearshift in the girl’s car and a semen stain consistent with Cooper’s DNA on the girl’s pants. At Cooper’s trial in the San Bernardino murder case, defense attorney Negus stipulated to the court without any objection from Cooper that he kidnapped and raped the teenager and that the crime unfolded in the manner she testified.

In an interview earlier this year, Cooper admitted that he had sex with the teenager, whom he had never met, but denied that it was rape. Following the San Bernardino conviction, Pennsylvania authorities did not pursue the case.

At the time of his July 1983 capture, nearly two months after the Chino Hills killings, Cooper — under a new alias — was being pursued for an unrelated charge of rape, stemming from an alleged assault on a boat near Santa Cruz Island. Santa Barbara prosecutors filed rape charges, but once he had been sentenced to death for the murders, officials elected not to take him to trial.

Joshua Ryen, the lone survivor of the 1983 attack, wrote to Brown in April, pleading with him to reject Cooper’s latest clemency petition.

“Kevin Cooper is a liar,” Ryen wrote. “He lies about everything. When he is caught in his lies, he lies more and more. He gets other people to believe in and broadcast his lies…This is ridiculous. It is obscene. Please deny Kevin Cooper’s requests.”

The man in the cage

While the debate continues outside San Quentin, the man at the center of it all sits on death row, arguing his innocence.

He writes for the media site TruthDig.com. He speaks with journalists and addresses gatherings from prison via phone. Nearly every day he contributes to his memoir. He calls it, “My Life on Your Death Row.”

This story was reported by Northwestern University students Michelle Galliani, Matt Zdun, Kelley Czajka, Juliette Johnson, Olivia Korhonen, Aysha Salter-Volz, Martin L. Oppegaard, Lila Reynolds, Bianca Sanchez and Hangda Zhang.

This reporting project was supervised by professors Peter Slevin and Patti Wolter. It was supported by The Medill Justice Project. Amanda Westrich, Allisha Azlan and Rachel Fobar also contributed to this report.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.