Sorry, ‘electability’ matters

- Share via

With an incumbent president like ours, it is no surprise that many American voters look at the current crop of Democratic challengers and say, “I’d be happy if any one of them were to win.”

It’s a perfectly rational attitude. Faced with the very real possibility of a disastrous Trump reelection next November, voters can be forgiven for feeling that even the vast ideological differences between, say, a moderate Democrat like Joe Biden and a democratic socialist like Bernie Sanders are relatively insignificant. Instead they ask themselves: “Which of these candidates is most likely to defeat Trump in 2020? Because that’s the person I want to vote for.”

But rational as that approach may seem — obvious, even — it has vehement opponents. In fact, there has been a sizable and vocal backlash in recent months against the idea that participants in Democratic primaries and caucuses should even consider “electability” when deciding for whom to vote.

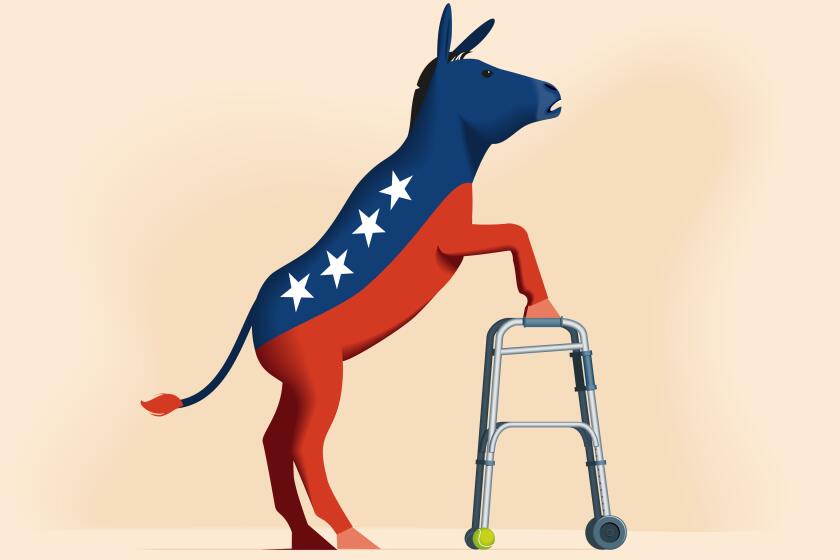

To some extent, this is an understandable reaction to the perception that “electable” is merely a code phrase for a more sinister argument: that the best shot the Democrats have of beating Trump is to put up a candidate who is white, older, male and likely to be acceptable to voters in the centrist mainstream of the country. Biden, who incarnates all of those identities, receives much of his support from Democrats who argue that he is the most — or only — electable Democrat.

Jill Biden, the former vice president’s wife, summed up that point of view with surprising candor when she said that voters who prefer other Democratic candidates might have to “swallow a little bit and say, ‘OK, I personally like so-and-so better,’ but your bottom line has to be that we have to beat Trump.”

“Swallow a Bit for Joe” is not a particularly inspiring campaign slogan, and it’s not surprising that voters who prefer other candidates would resent the implication that they should subordinate their political convictions to some old-fashioned, politically distasteful conception of who is most likely to win. If electability becomes Biden’s message and he secures the nomination, he could face lingering resentment that could dampen enthusiasm and reduce turnout in the general election.

Besides, who says that an old centrist white guy will inevitably be the most electable? Biden, for instance, might be perceived by many voters as too old or addled or gaffe-prone, or as damaged goods. Certainly, the recent news about his son’s lucrative work in Ukraine has not helped his case. Perhaps, after all, the enthusiasm with which young voters on campus greet a Sanders or Elizabeth Warren would make one of them a better general election candidate. Maybe Kamala Harris — who is younger, not too far left and apparently more than capable of standing up to Trump to his face — has the mix of qualifications it takes to win.

While it is no doubt true that there are general election voters who would be more likely to support a white man than a female or black candidate, there’s no evidence that their votes would be dispositive. And although the votes of moderates, independents and swing voters are important in any general election, it is not by any means certain that any centrist would do better in a general election against Trump than any progressive.

And here’s another thing to keep in mind: The so-called experts aren’t always right about who can win and who can’t. Don’t forget how many observers in 2008 were convinced that Barack Obama, a little-known, first-term African American senator, was unelectable. They were spectacularly wrong, as were those who insisted that Donald Trump couldn’t possibly defeat the much more credentialed (and moderate) Hillary Clinton in 2016. (Clinton did, of course, win the popular vote.)

Voters should not be indifferent to whether particular candidates seem more or less likely to defeat Trump.

So any discussion of electability must come with caveats and qualifications. It’s important not to define the concept too narrowly, or to assume that the most electable Democrat will be the one who looks or sounds most like our previous presidents. The candidates have to prove over the coming months in a variety of settings how viable or non-viable they will be. Do they strike voters as “authentic”? Will they be able to hold their own on the debate stage with Trump? The title of “most electable” is still up for grabs.

Still, it seems to us bizarre to reject the importance of electability as one factor voters should consider during the run-up to next year’s Democratic convention. The primary and caucus process isn’t simply a preference poll. It is designed to position the party to win the presidency in November.

That aspect of the process was perhaps more obvious in the days when nominees weren’t chosen until the convention and party leaders in smoke-filled rooms called the shots. But even though primaries and caucuses have taken on much greater importance in recent years, selecting a nominee who can win is of course still the central goal.

For most voters, deciding whom to support is a complicated process that involves weighing the candidates’ policy positions, their experience, their leadership abilities, their backstories and many other qualities. That’s as it should be. Our point is only that voters should not be indifferent to whether particular candidates seem more or less likely to defeat Trump. We’re not proposing that primary voters reflexively ratify the standing of candidates in the latest public opinion poll, nor are we calling for them to support a seemingly competitive candidate they consider deeply objectionable.

We are saying that Democrats participating in primaries and caucuses must keep their eye on the overriding objective: ending the misrule of Donald Trump. Achieving that objective is vital even if it means supporting a candidate who may not be first on one’s list of ideal potential presidents. Electability isn’t everything, and it isn’t always easy to identify, but it’s important — especially in this terribly consequential election.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.