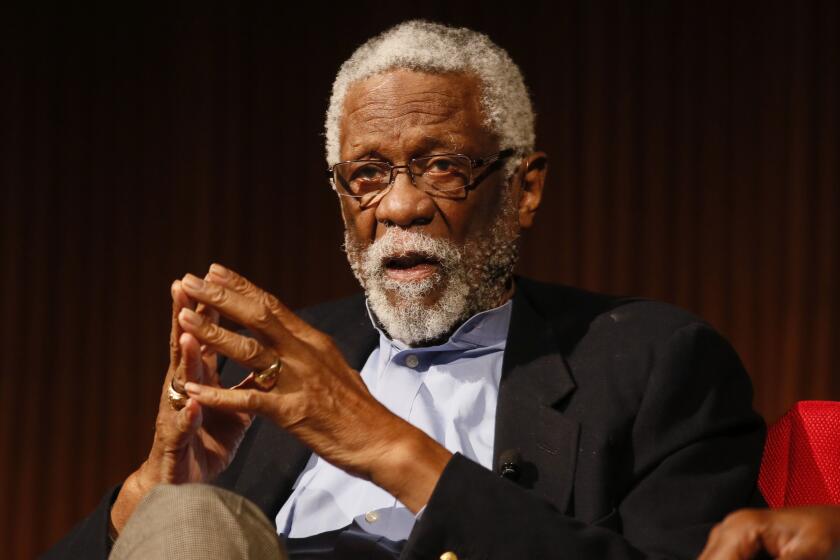

Bill Russell, legendary Celtics center and NBA coach, dead at 88

- Share via

Years after he stepped away from the game of basketball, Bill Russell’s complicated relationship with the city where he spent his career continued to burn so deeply that he decided to skip his induction into the Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Mass.

“I don’t care if I ever go to Boston again,” the former Celtic said.

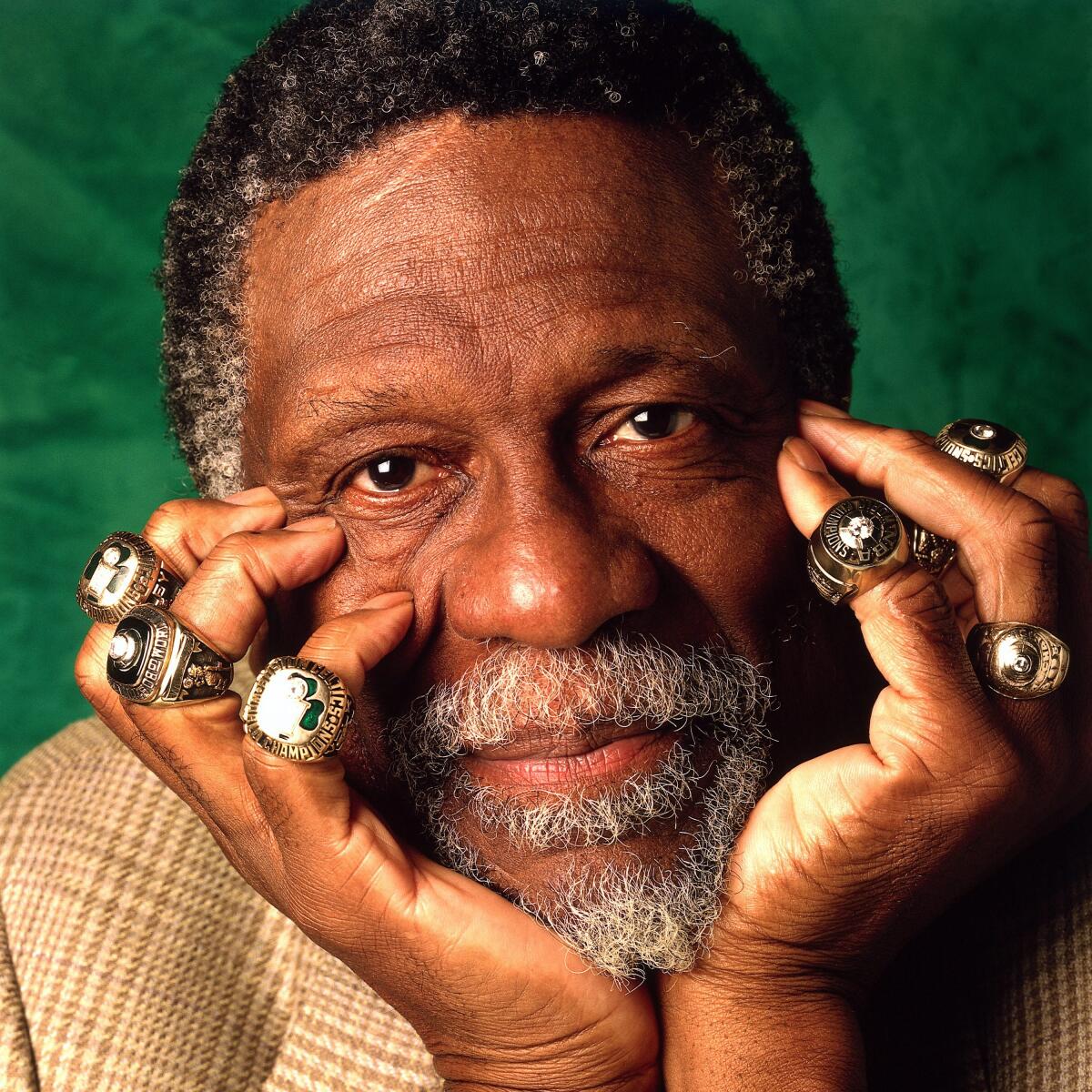

It was emblematic of his relationship with a city he helped carry to basketball glory again and again, 11 championships in all, seven times at the expense of the Lakers. Russell loved the team, his teammates, his coach and the championship banners that fluttered high above the parquet floor of Boston Garden.

But he also believed the city had refused to embrace him because he wasn’t white.

Russell, professional basketball’s first Black superstar and a game-changing big man who reinvented the center position with the dynastic Celtics of the late 1950s and ’60s, died Sunday at 88, according to a family statement. A cause of death wasn’t given, nor did the statement say where he died.

“Bill stood for something much bigger than sports: the values of equality, respect and inclusion that he stamped into the DNA of our league. At the height of his athletic career, Bill advocated vigorously for civil rights and social justice, a legacy he passed down to generations of NBA players who followed in his footsteps,” NBA Commissioner Adam Silver said in a statement.

A private man in a very public occupation, and plying his unique talents in a city then notorious for its racial divisions, Russell led the team to championships in all but two of his 13 pro seasons, including eight consecutive titles, a figure unprecedented then and unmatched since by any U.S. team in any professional sport.

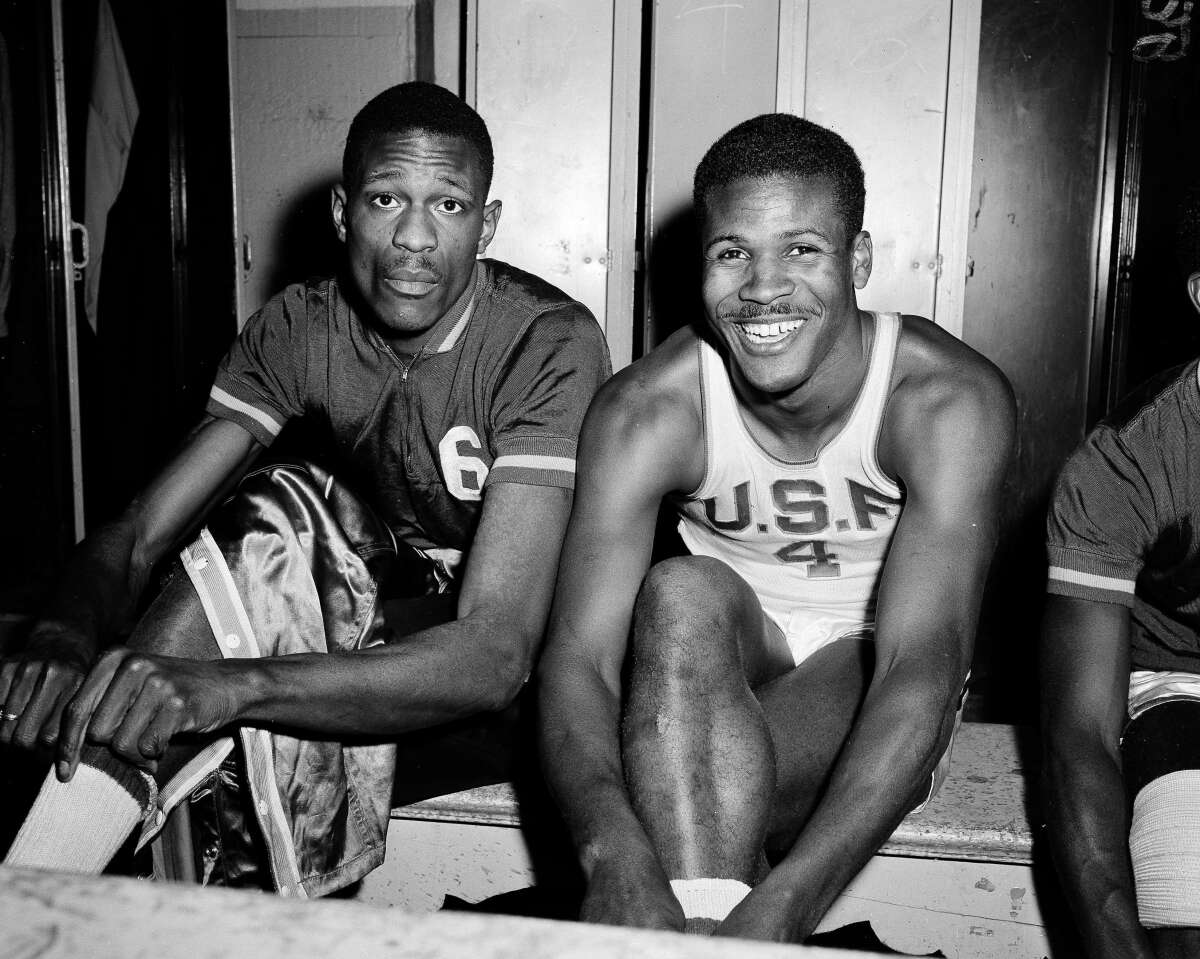

Before joining the Celtics, Russell helped the University of San Francisco to two national collegiate championships in a row, and the United States Olympic team to the title in the 1956 Melbourne Games, giving him the rare distinction of having played on teams that won NCAA, Olympic and NBA titles in a span of only 13 months.

During his years with the Celtics, Russell was named to the East All-Star team 11 times and won the league’s Most Valuable Player award five times. The NBA honored him by naming the playoff finals MVP award for him in 2009. Two years later, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Obama. And, as he was closing down his playing career, he became the first Black head coach in any U.S. professional sport.

Perhaps just as impressive, Russell introduced defense to a league that, in its infancy, was built on scoring. He didn’t originate shot blocking, but he did make it an art form, leaping high to swat opponents’ shots away.

“What I saw was an incredibly talented and athletic big man, but more than that a player bringing a dimension to the game that had never been seen before,” former teammate Tommy Heinsohn told the Boston Herald in 1999. “He could absolutely control a game defensively.... His defensive genius was something completely foreign to the NBA.”

Boston Celtics Hall of Famer Bill Russell died at age 88 on Sunday. Here is the Los Angeles Times’ coverage of Russell’s achievements on and off the court.

For Russell, it was a style he’d developed at USF, much to the consternation of his coach, Phil Woolpert, who maintained that a defensive player should never leave his feet. Somehow, though, Woolpert reconciled his traditional beliefs with Russell’s abilities and gratefully accepted the two national championship trophies his 6-foot-10 center brought him.

“We changed the game,” Russell told Sports Illustrated, recalling his years at USF. “I think you can even say we developed a whole new philosophy of basketball.”

But it was not simply the abundance of championships that set Russell apart.

Russell was that rare star athlete during his time who spoke publicly about various issues that centered on racism and the importance of fighting for equality.

As early as 1958, he said the NBA had an unwritten quota system that effectively held back Black players, noting that no team at the time had more than three.

Russell was an early participant in the civil rights movement that was gaining momentum by the mid-1960s. He went to Mississippi in 1961 to lend support to the Freedom Riders protesting segregation and participated in the March on Washington for civil rights in 1963.

Russell also conducted integrated basketball clinics in Jackson, Miss., after the 1963 assassination of civil rights leader Medgar Evers.

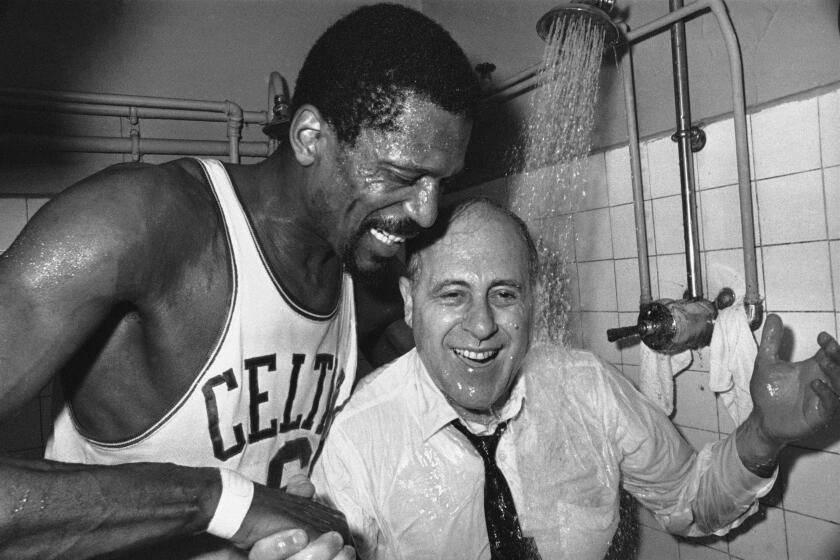

During a Southern swing of exhibition games with the Celtics, he told Red Auerbach that he and the other Black players would not play that night in a small Kentucky town, since they had been turned away by the hotel where the rest of the team would be staying. The coach was understanding.

One season, Russell’s teammates joined him in the Boston suburb of Reading, where he lived, as the town gathered to honor him as the Celtics’ captain. A few months later, apparently in retaliation for that honor, vandals broke into his Reading house, smashed his trophies, defecated in his bed and smeared excrement on the walls.

Ever his own man, Russell failed to show up at the Basketball Hall of Fame ceremony in 1975 when he was inducted, the first Black player to be selected, because he believed it was a racist institution, Sports Illustrated reported. He was later named to the Hall as a coach, only the fifth person to be duly honored.

Russell was a vocal critic of the Vietnam War and spoke out on behalf of Muhammad Ali when the celebrated boxer refused to fight

Russell’s high-profile stands could have jeopardized his NBA career, but he refused to be silenced on matters of harmony, unity and racial injustice.

Former NFL star running back Bobby Mitchell said Russell “stood up for things that we needed to stand up for. During the years that Bill was playing, he was one of the few Black athletes that those of us in the sports [world] really looked up to. But we held on to the future just merely by watching and listening to the Bill Russells and the Jim Browns and those people who were outspoken.”

As good as he was, Russell was never a fan favorite in Boston, which preferred Bob Cousy, John Havlicek, Bill Sharman and Heinsohn, all shooters — and all white.

By 1966, at the height of his career, he had little good to say about Boston. “A poisoned atmosphere hangs over this city. It is an atmosphere of hatred, mistrust and ignorance.”

If Boston chose not to embrace Russell, part of the reason was that he was not very embraceable. He figured that his duty to the fans was to play the best he possibly could — period. He stubbornly refused to sign autographs, even when teammates requested them.

Lakers legend Jerry West says NBA great Bill Russell made a difference on the lives of everyone around him. “I admired him so much as a human being.”

He came into the world as William Felton Russell on Feb. 12, 1934, in Monroe, La., the younger son of Charles, a janitor in a paper bag factory, and Katie Russell. Among his early childhood memories was one of a trip to an icehouse, where the attendant kept the family waiting while he served white customers. Irked, Russell’s father began to pull away.

“The attendant ran over to Dad’s window and said, ‘Don’t ever try to do that, boy, unless you want to get shot.’ He had a big gun. My dad picked up a tire iron and got out of the car and the redneck just turned and ran for his life, “ Russell recalled in his memoir “Go Up for Glory,” written with William McSweeny.

Later, hoping to better the family’s circumstances, Charles Russell moved to Oakland, where he eventually found work in a plant geared to World War II production. Life in California was an improvement, though not by much.

“I couldn’t even go downtown,” Russell recalled. “The cops would chase the Black kids away.”

There was family strife as well. Charles and Katie separated and when Katie died a few years later, Bill and older brother Charlie, although living with their father, essentially raised themselves.

Charlie was a pretty good basketball player, but Bill struggled. An awkward, gangling kid, he failed to make the team at Hoover Junior High School. At McClymonds High, he barely made the junior varsity, alternating with another player in wearing the team’s 15th uniform. As he grew and filled out, however, he gained poise on the court.

Boston Celtics legend and NBA Hall of Famer Bill Russell died on Sunday at the age of 88. A look at his life on and off the court in pictures.

Hal DeJulio was one of the few who noticed. DeJulio had played at USF and sometimes steered marginal young players in that direction. Watching a game between Oakland High and McClymonds, he was taken with the long-armed center. A week later, DeJulio showed up at the Russell household and offered Bill a scholarship to USF.

The Dons, under coach Pete Newell, had won the 1949 National Invitation Tournament championship, at the time only slightly less prestigious than the NCAA title, but Newell had moved on and USF was struggling to regain its basketball stature.

With Russell, as well as future Celtics teammate K.C. Jones, the Dons regained it in a hurry. Russell was honing his defensive skills, but he was a scoring threat as well, and led the way as USF won national championships in 1955 and ’56, running up a then-record 55-game winning streak in the process.

Russell’s development in college was pointed out quickly to Auerbach, who in addition to coaching the Celtics made personnel moves as a team executive.

Getting him, though, took some finagling. The Celtics, having finished second, did not have a high first-round pick. In fact, because they were taking Heinsohn, of Holy Cross, as a territorial pick, they had to forfeit their first-round pick altogether. So Auerbach started thinking trade.

And on draft day, the St. Louis Hawks made Russell the second pick of the draft, then turned him over to Boston, getting center “Easy” Ed Macauley, who’d been a local hero in St. Louis, and the rights to Cliff Hagan, who was returning from Army duty. Both Macauley and Hagan went on to Hall of Fame careers with the Hawks.

“Did I know what I was getting?” Auerbach asked. “Not really. A great rebounder, sure. But I never knew about his character, his smarts, his heart — things like that.”

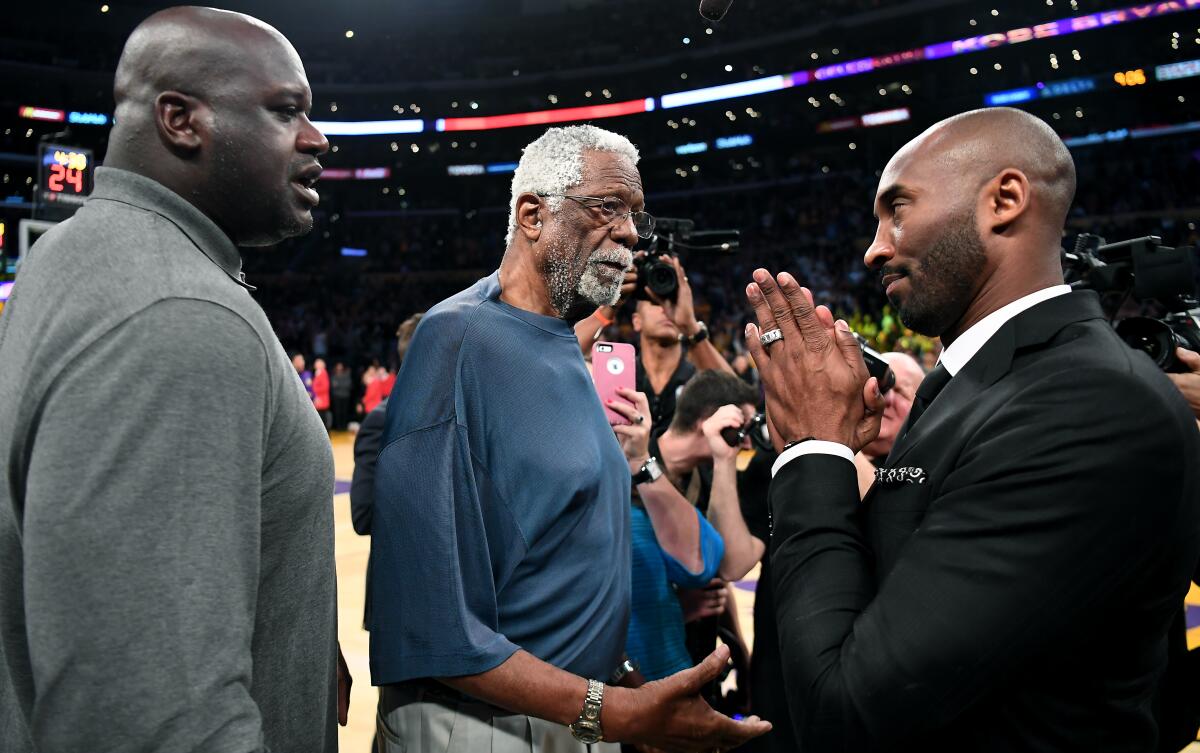

Kobe Bryant’s path to greatness in the NBA seemed assured. But it would not be easy.

Russell fit in quickly and the Celtics turned basketball into a leaping, fast-breaking vertical exercise and won the first of their many championships. Along the way, the shot-blocking Russell and the high-scoring Wilt Chamberlain developed one of the most memorable rivalries in NBA history, but the Celtics, with better overall personnel, usually beat Chamberlain’s teams.

When Auerbach decided to step away from coaching after the 1965-66 season, he turned the team over to Russell as player-coach. The Celtics stumbled slightly in Russell’s first season of coaching and Chamberlain’s Philadelphia 76ers won the championship, but the Celtics regained their traditional upper hand and won championships the next two years.

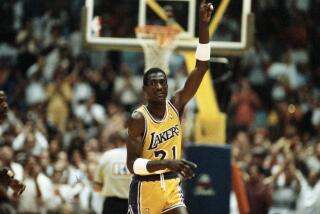

In fact, they won the title in Russell’s final season, beating Chamberlain, by then with the Lakers, in the famous “balloon game” finale at the Forum, Lakers owner Jack Kent Cooke’s new basketball palace. The Lakers, with Jerry West and Elgin Baylor, as well as Chamberlain, had given the Celtics as much as they could handle, the series was tied at 3-3, and so confident was Cooke that the Lakers would win in Game 7 at home that he had balloons suspended from the Forum rafters, to be released after the Lakers had won.

Final score: Celtics 108, Lakers 106.

What Russell had kept to himself was that the game would be his last in the NBA. He didn’t propose to lose it, and the balloon scenario, which had been publicized ahead of time, only firmed his resolve.

“I knew they couldn’t win it,” he said of the Lakers years later. “I just knew it.”

In retirement, Russell had an eclectic career. He would disappear from public consciousness for months, sometimes years, at a time, then suddenly show up in a movie or on a TV commercial. He was a sometime NBA analyst and he had two more coaching stints, bringing the Seattle SuperSonics to respectability in the ’70s, then serving a forgettable two-season stint with the Sacramento Kings in the ’80s.

In 1999, Russell’s jersey was re-retired in an emotional public ceremony at FleetCenter (now TD Garden) in Boston. The event was emceed by Bill Cosby and attracted Chamberlain, Auerbach, Celtics great Larry Bird and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. Russell was greeted with a standing ovation that brought him to tears.

“I had an agenda,” Russell said later. “And that was to win as many championships as possible. There may be a debate as to who was the best player, but there can be no debate as to who won the most championships.”

In 2017, Russell wore his Presidential Medal of Freedom in a photo posted of him taking a knee. Russell explained that he was making a statement about social injustice while supporting Colin Kaepernick, the former San Francisco 49ers quarterback who knelt during the national anthem of NFL games in a demonstration against police brutality and racial injustice.

A few months earlier, Russell was presented the Lifetime Achievement Award at the inaugural NBA Awards. And in 2019, Russell was named the recipient of the Arthur Ashe Courage Award at the ESPYS.

Former Georgetown coach John Thompson, in one of many video tributes at the ESPYS that included warm praise from Obama and Abdul-Jabbar, said that “Russell didn’t wait until he was safe to stand up for what was right. Russell did that in the midst of winning 11 championships. He represented things that were right while he had something to lose.”

He even softened his view of Boston, saying the city also was rough on Red Sox slugger Ted Williams so “maybe it’s just a tough town for athletes.”

Teams, sports figures and celebrities shared their condolences and thoughts on the passing on NBA Hall of Famer Bill Russell.

“He’s mellowed,” said Cousy, “and is allowing himself to reach out and communicate with people who want to have a relationship with him.”

Russell married his college sweetheart, Rose Swisher, in 1956 and they had three children, Karen, William Jr. and Jacob. They divorced in 1973 and Russell married Dorothy Anstett, a former Miss USA, in 1977, then divorced her three years later. He married his third wife, Marilyn Nault, in 1996 and their marriage lasted until her death in 2009.

He is survived by his wife, Jeannine, and two of his children, Karen and Jacob. His son William Jr. died in 2016. His brother Charlie, a noted playwright, died in 2013.

Kupper is a former Times staff writer and Eisenhammer is a former Times news editor.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.