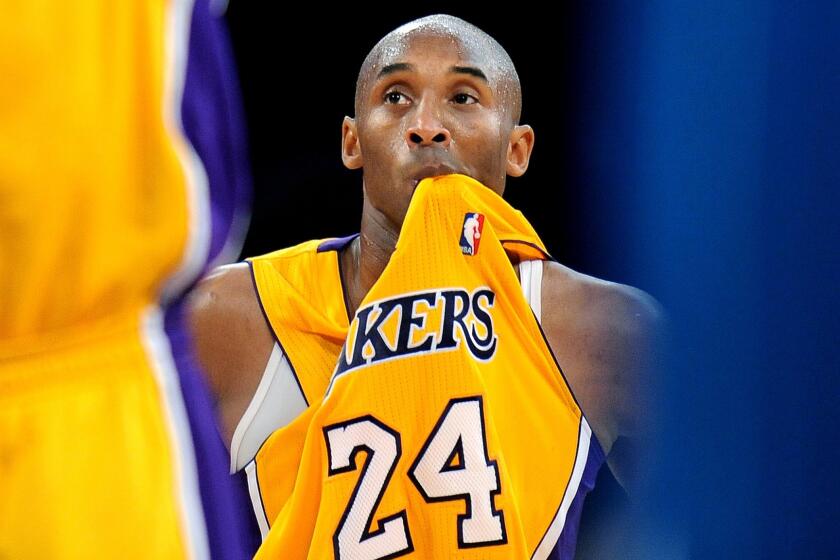

Kobe Bryant, from the start, was an athlete like no other

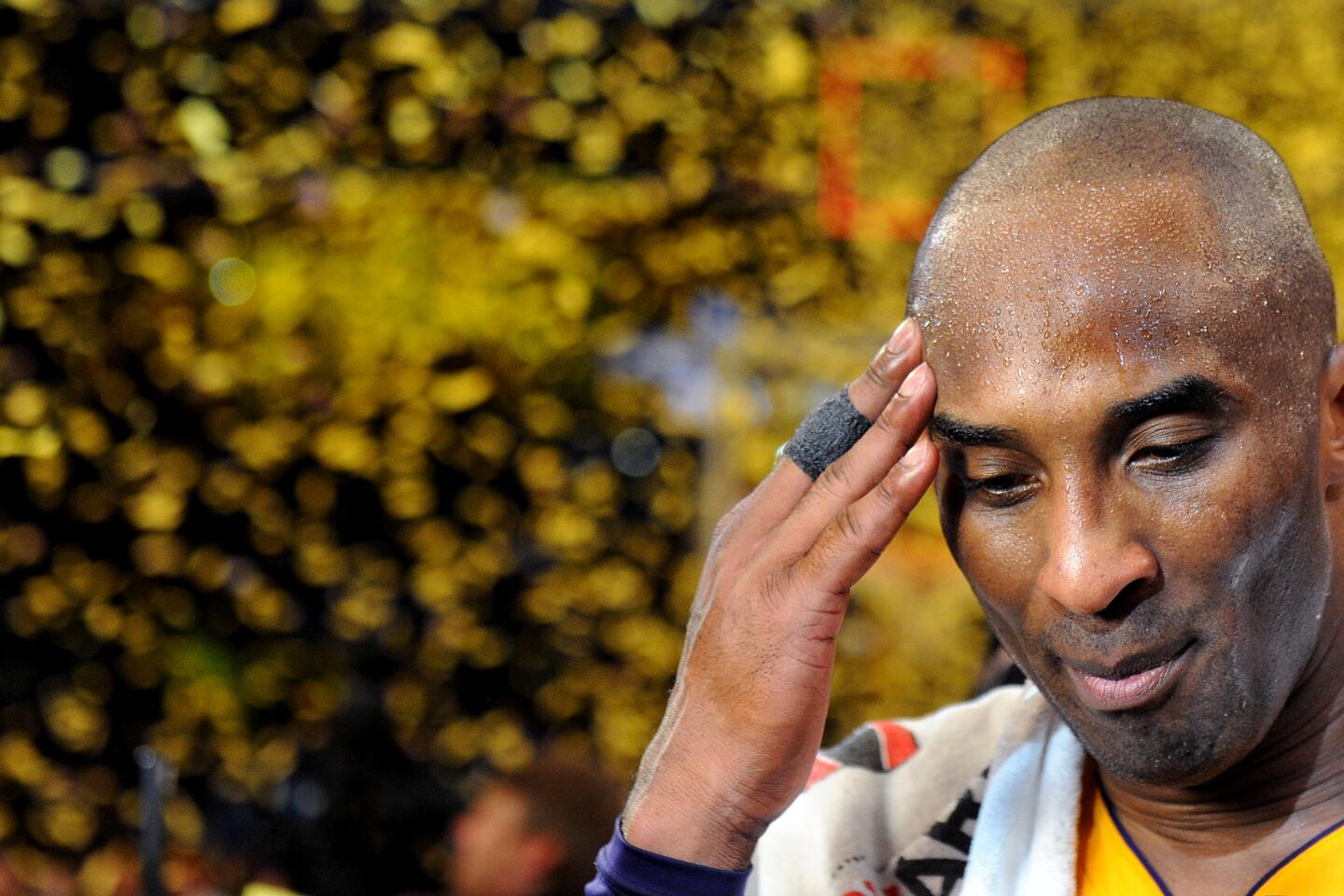

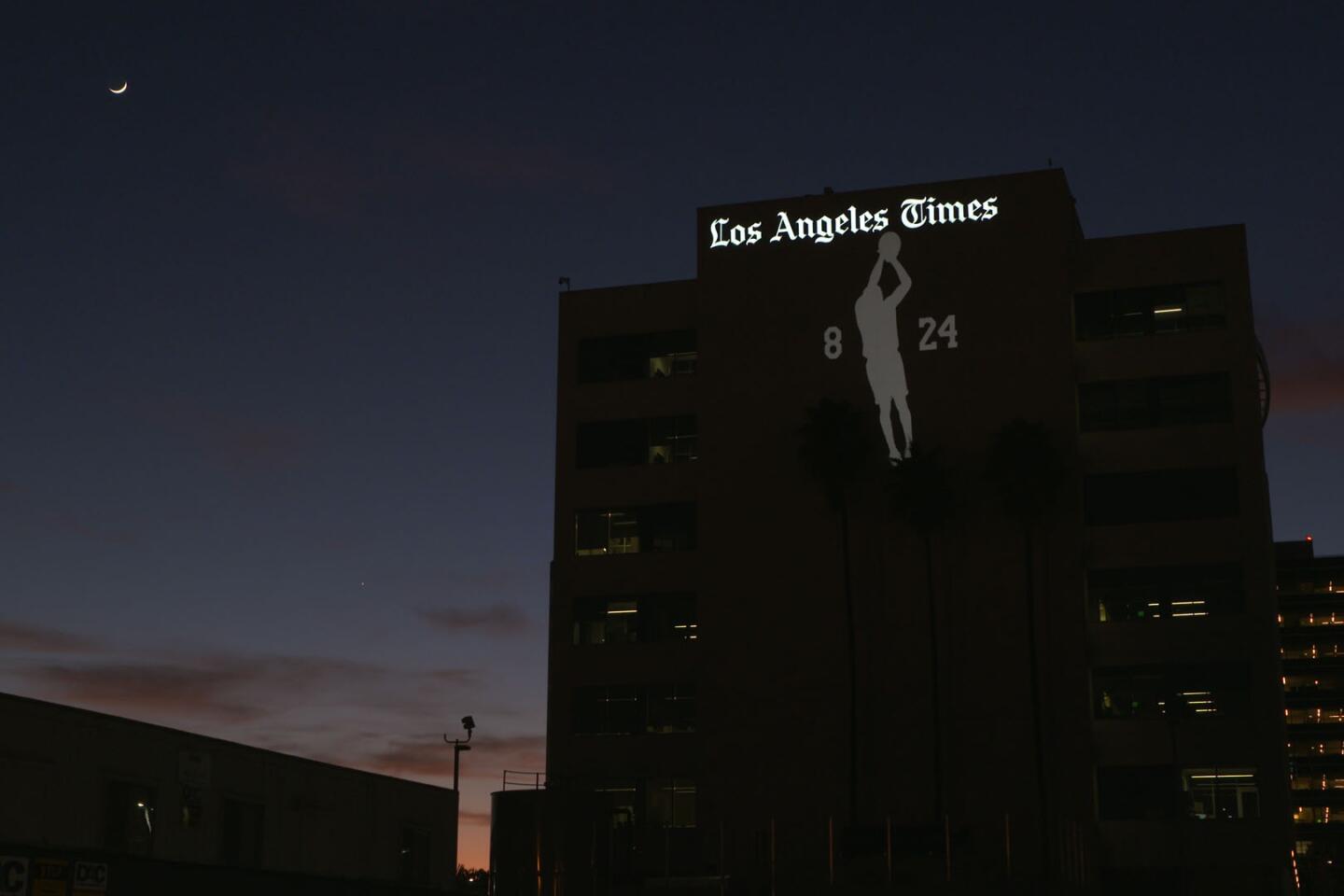

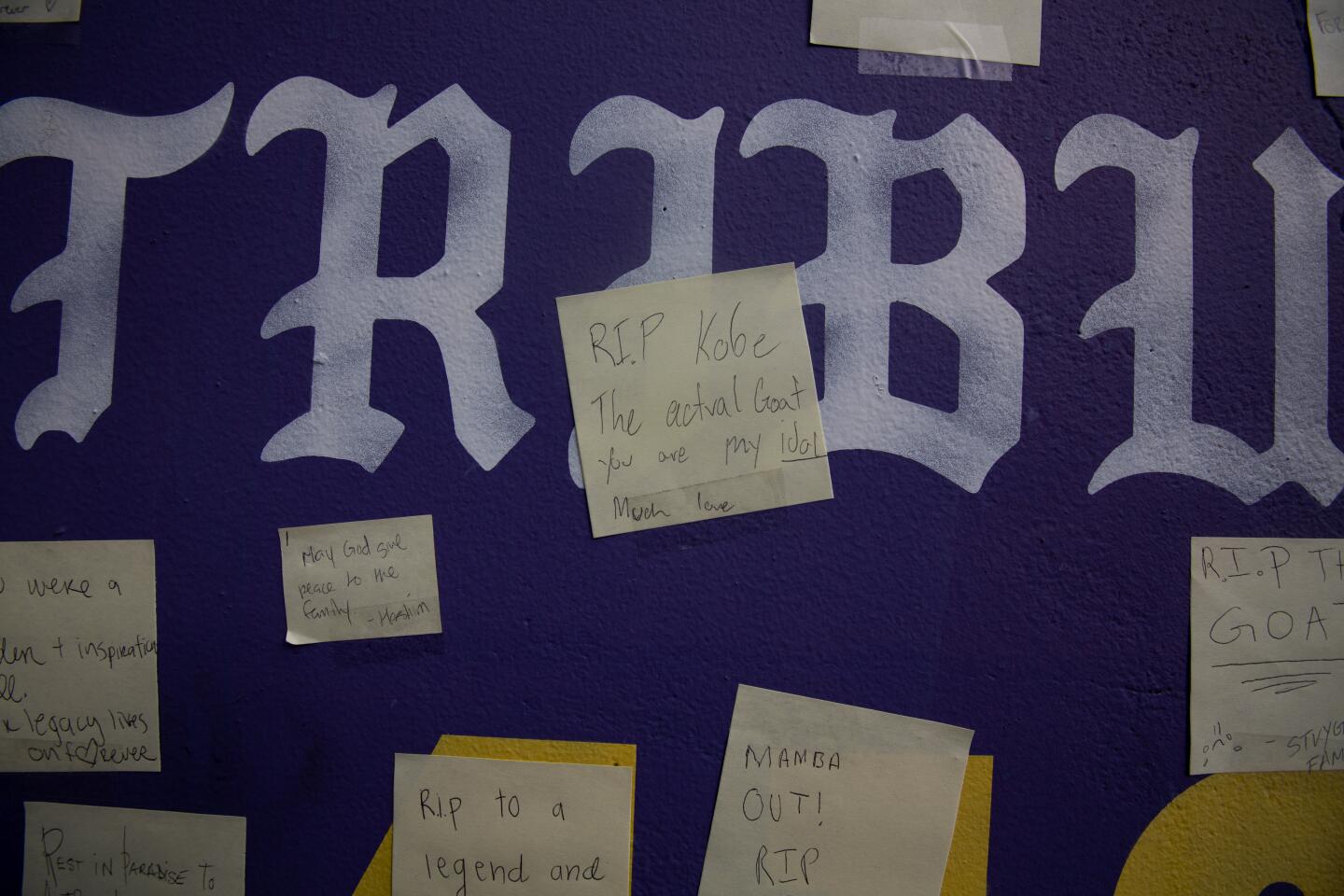

L.A. mourns the death of Lakers legend Kobe Bryant.

- Share via

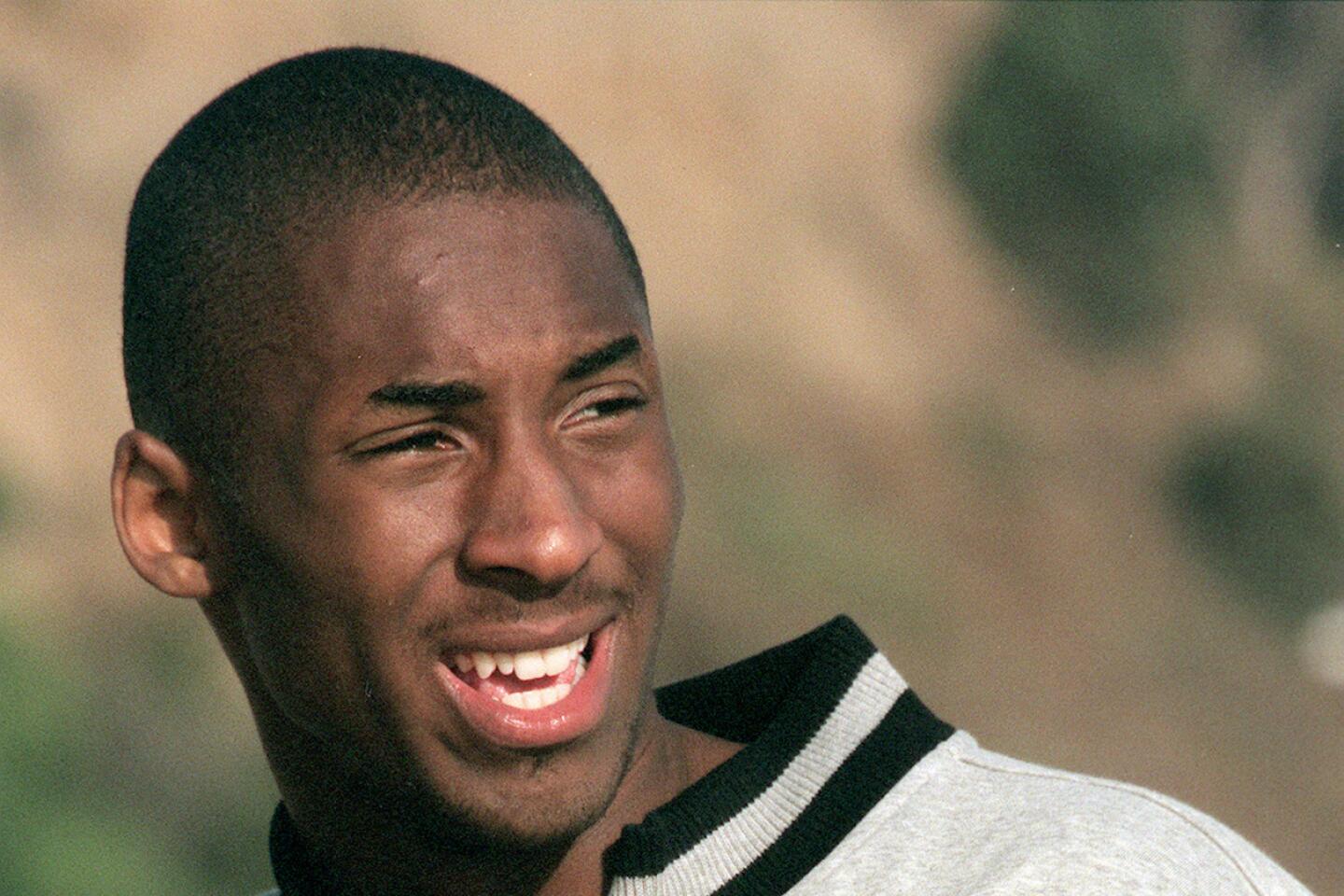

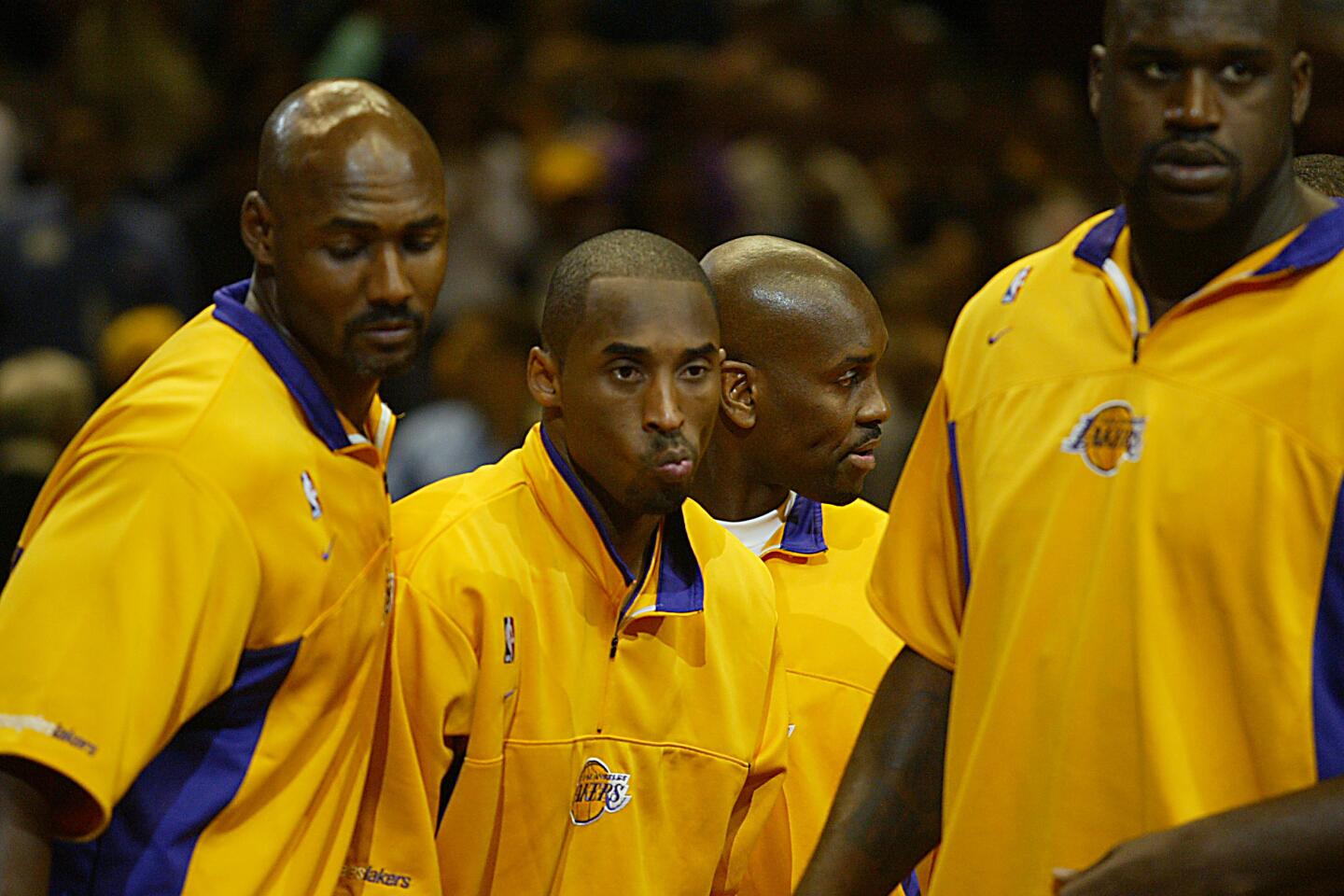

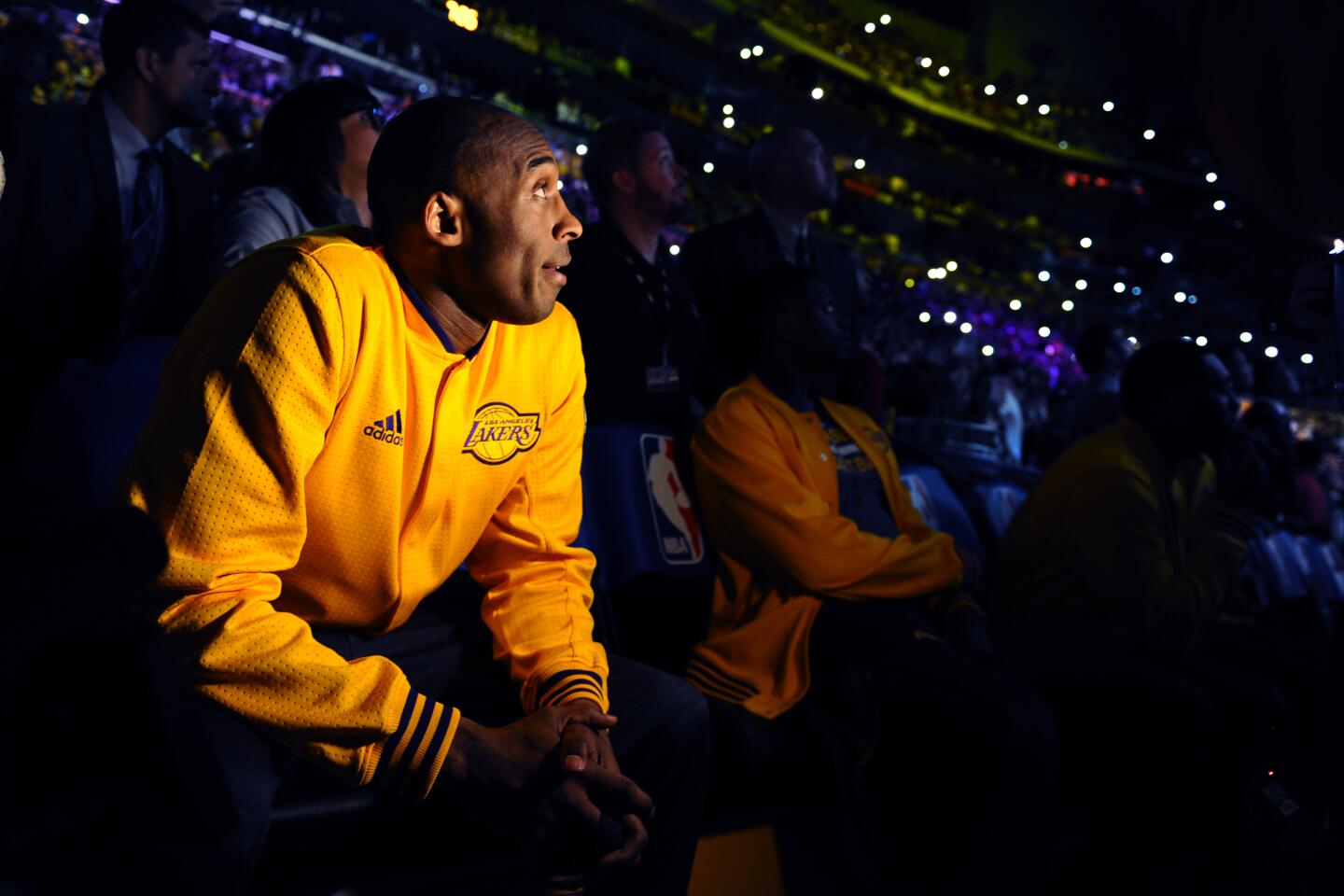

From the very start when Kobe Bryant played his first game for the Los Angeles Lakers as an 18-year-old basketball phenom, his path to greatness seemed assured. But it would not be easy.

The NBA wasn’t convinced that any player, no matter how sensational or talented, could jump directly from high school to the big leagues.

But Bryant was a different sort of athlete, the son of a well-to-do Philadelphia family who spent his formative years in Europe. His unusual upbringing and steely determination — holding himself and those around him to the highest standards — sometimes led to friction with coaches and teammates.

None of that could stop the 6-foot-6 shooting guard from becoming one of the greatest in the history of the game, equally dangerous driving to the basket or shooting from outside. None of it could dull the sense of shock that came over Los Angeles, a city that grew to love him, when he died Sunday in a helicopter crash that also took the lives of his 13-year-old daughter, Gianna, and seven others.

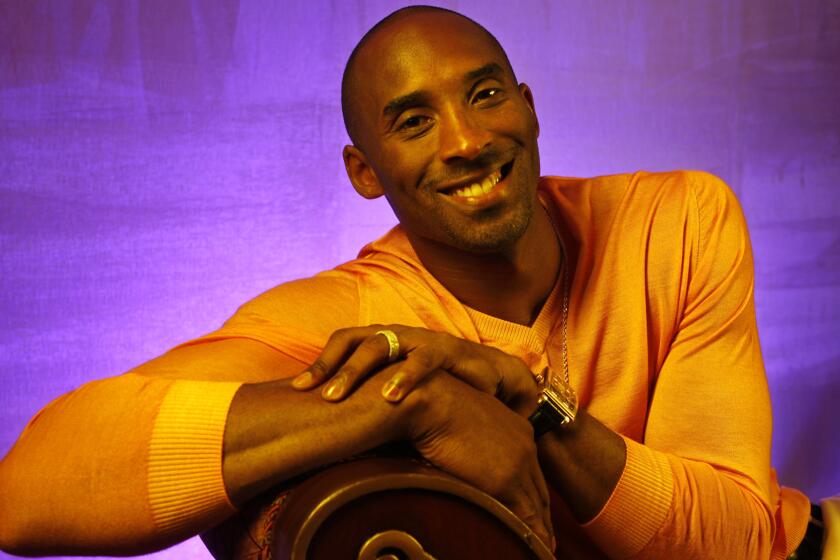

“Just to see the joy he played the game with, the joy he brought to fans, was pretty remarkable,” Lakers great Jerry West said. “You don’t get players of that skill and that caliber that are able to do those things and bring that joy.”

Lakers legend Kobe Bryant died when the helicopter he was traveling in crashed into a hillside in Calabasas shortly before 10 a.m.

Magic Johnson called him “a different cat,” and he was. Opposing teams — wary of his ability to control the game, fearful of his shooting streaks, his maverick prowess — assigned players, known as “Kobe stoppers,” to harass him on court.

He called himself Black Mamba, a code name for an assassin in one of Quentin Tarantino’s films. But his aggression and agility on the court came with a darker side as well.

Midway through his career, in July 2003, Bryant was accused of rape by a hotel employee. The criminal case, which drew national attention when salacious details were leaked, was ultimately dropped after the woman refused to testify. In an ensuing civil suit, Bryant settled and apologized without admitting his guilt.

The Times is offering select coverage of Kobe Bryant’s death for free. Please consider a subscription to support our journalism.

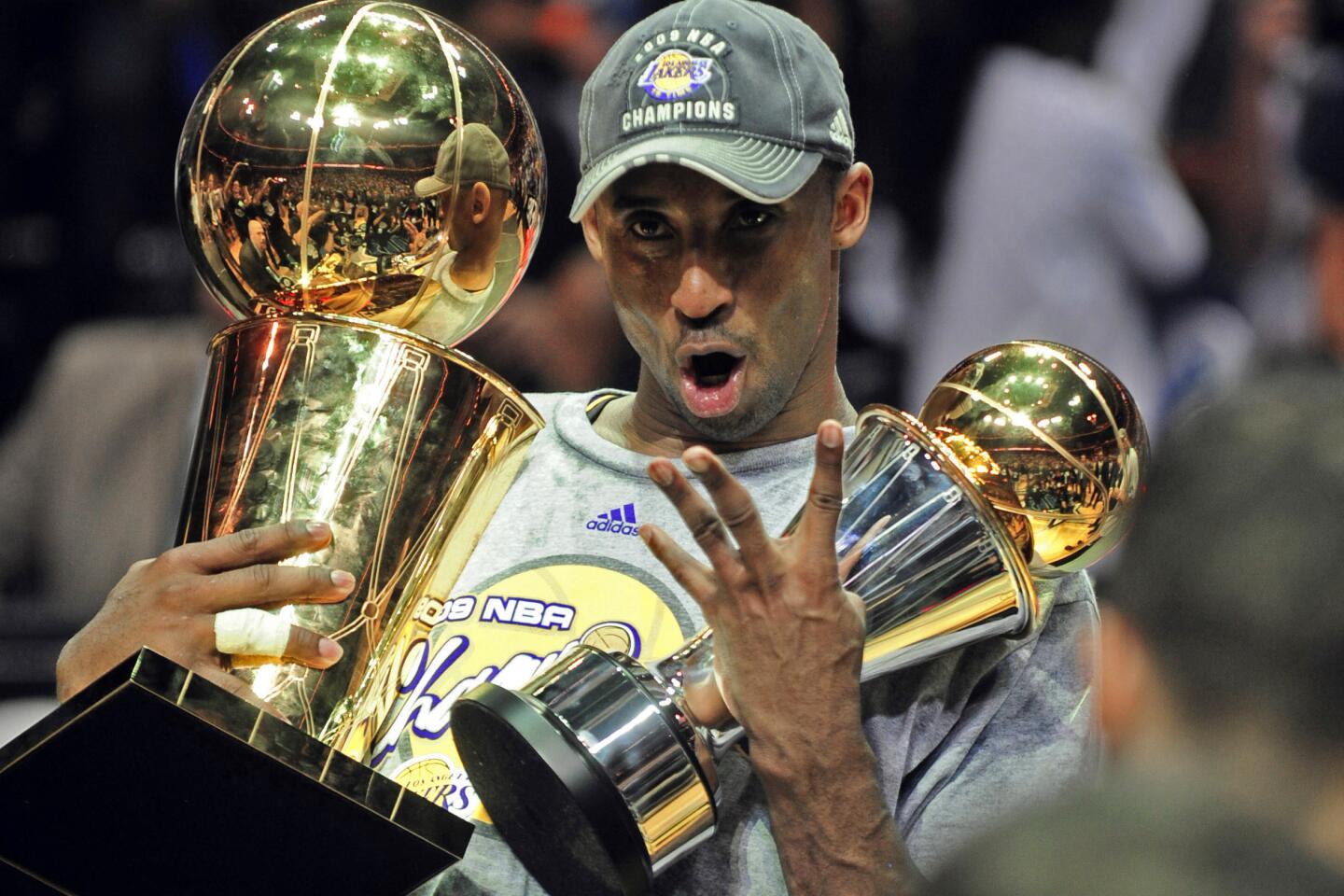

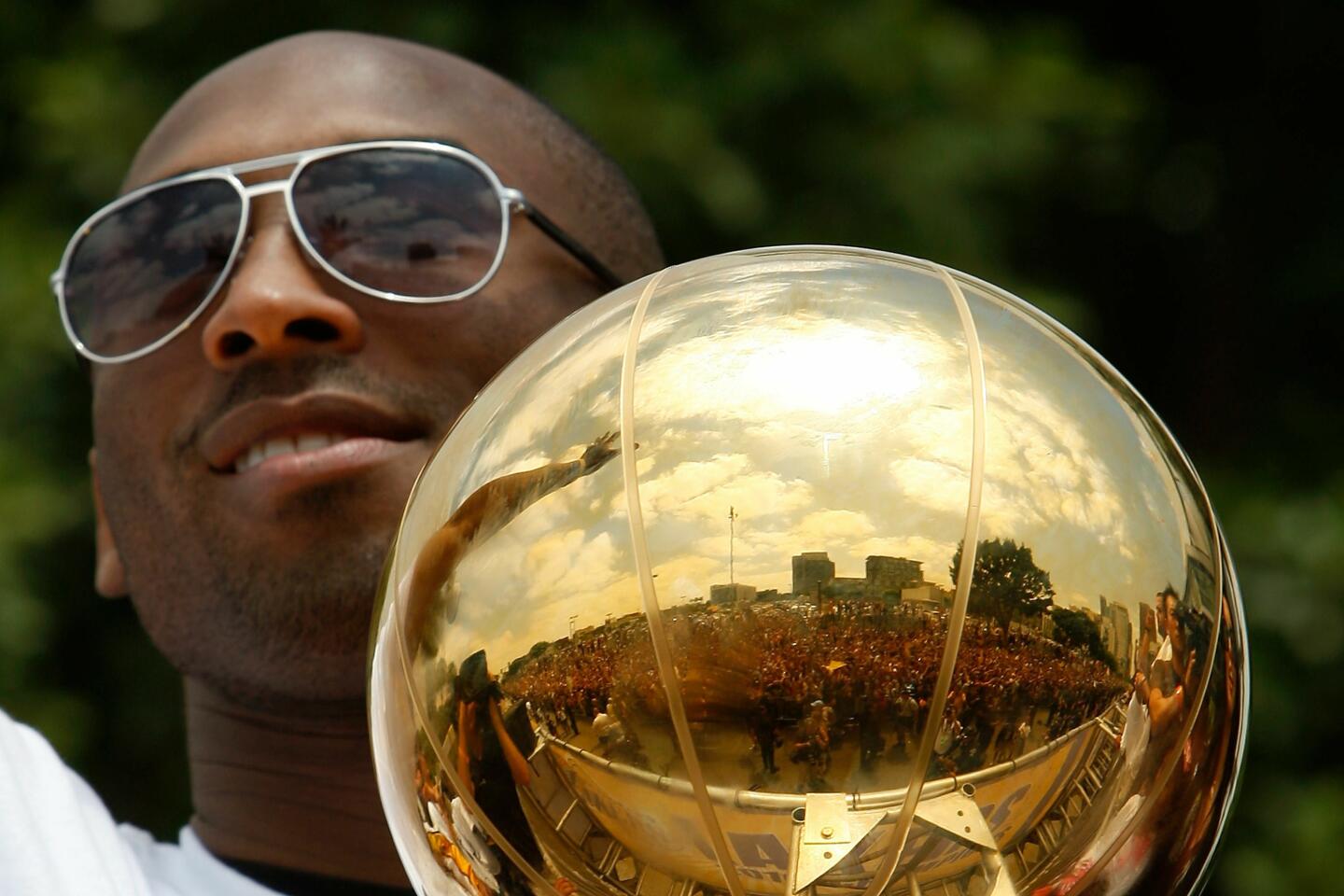

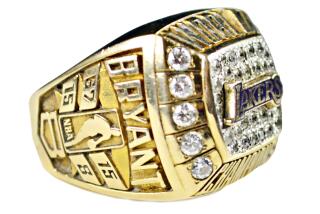

By the end of his 20-year career — all of it spent with the Lakers — Bryant was a five-time world champion, two-time Olympic gold medalist with the U.S. team and 18-time All-Star. He ranks fourth on the NBA’s all-time scoring list; he was surpassed just this weekend by Laker star LeBron James.

In a manner befitting both his sophisticated background and the city where he spent his adult life, the 41-year-old had transitioned from athletic stardom to a post-basketball career that included an Oscar for the animated short “Dear Basketball,” a series of children’s books that became New York Times bestsellers and a growing business empire.

“Kobe was a legend on the court and just getting started in what would have been just as meaningful a second act,” former President Obama said in a statement.

As federal authorities launched an investigation into the crash that took place on a foggy morning in the hills above Calabasas, teams across the NBA honored Bryant, some by standing absolutely still on the court, letting the clock tick its way to a 24-second violation, matching the number that Bryant wore for much of his time in the league.

“Most people will remember Kobe as the magnificent athlete who inspired a whole generation of basketball players,” former Laker Kareem Abdul-Jabbar posted on social media. “But I will always remember him as a man who was much more than an athlete.”

::

Basketball ran in Bryant’s lineage.

His father, Joe “Jellybean” Bryant, played eight seasons in the NBA, including three for the then-San Diego Clippers. When the elder Bryant and his wife, Pam, had a son on Aug. 23, 1978, they named him after the city in Japan.

“It was the ’60s,” Joe said. “We weren’t naming kids Joe or John.”

The Bryants moved overseas so Joe could play for a series of Italian pro teams after his NBA career ended. Kobe was 6 at the time and was obsessed with basketball, watching videotapes of U.S. games mailed to him by his grandfather.

The Lakers were his favorite team. He idolized Elgin Baylor — “the footwork king” — and admired the way West could fire a quick jump shot or smoothly cut to the basket. His greatest admiration was reserved for Johnson, who had a sixth sense on the court, anticipating plays as they developed, delivering the ball precisely where it needed to be.

Returning to the U.S. as a teenager, Bryant stood out among his classmates at Lower Merion High in Ardmore, Pa., speaking fluent Italian and earning a high score on his SAT. He was even better on the basketball court.

Kobe Bryant was our childhood hero, our adult icon. It seems impossible to believe he has died at age 41.

Averaging more than 30 points and 10 rebounds a game, he broke Wilt Chamberlain’s record as the leading high school scorer in the history of the Philadelphia area. Still, there was skepticism when the 17-year-old made himself available for the 1996 NBA draft.

Though scouts characterized him as “borderline sensational,” young players were expected to spend at least a few years honing their skills at the college level.

“Sure he’d like to come out,” an NBA scouting director said at the time. “I’d like to be a movie star. He’s not ready.”

Bryant had no doubts, showing the sort of bravura that could — at times — irritate his critics.

“I know that I’ll have to work extra hard, and I know that it’s a big step,” he said. “I can do it.”

If Kobe was young, he was also confident. He saw for himself a future beyond the suburbs of Philadelphia. Needing a date for the prom, he invited Brandy Norwood, a pop singer and star of the “Moesha” sitcom.

::

The Lakers were a team in transition in the mid-1990s. Johnson, Abdul-Jabbar and James Worthy had retired. A lineup featuring the likes of Vlade Divac and Elden Campbell had yet to re-create the glory of the “Showtime” era.

Looking for something more, team officials had their eye on two possible additions. There was Shaquille O’Neal, a hulking center for the Orlando Magic, on the free-agent market. And there was the kid from Pennsylvania.

The Charlotte Hornets had chosen Bryant with the 13th pick of the 1996 draft, based on scouting reports that described him as “a good ball handler, a slashing driver and, depending on when you see him or whom you talk to, a decent or erratic outside shooter.”

As the Lakers’ executive vice president, West saw great potential. The guard-turned-executive worked a trade, sending Divac to Charlotte in exchange for Bryant.

Remembering a rare athlete whose greatness was matched by a desire to win

Bryant was still 17, so his parents had to co-sign the three-year, $3.5-million contract the team offered him. The hype began immediately with his pro debut in a summer league game against a Detroit Pistons squad at Cal State Long Beach.

“He was, by far, the most skilled player we’ve ever worked out,” West said. “This is not a 17-year-old kid. Period.”

Less than a month later, the team also added the 24-year-old O’Neal who, at the time, was being touted as the second coming of Abdul-Jabbar. Just that quickly, L.A. had a duo that would bring both championships and a few headaches for years to come.

In those early days, Bryant bought a Pacific Palisades home, where he lived with his parents until they eventually moved a quarter-mile away. He signed an endorsement contract with Adidas and obtained a Screen Actors Guild card for the roles he was now playing not only on “Moesha” but also on “Arli$$,” a cable show about a sports agent.

It would be a mistake to think money or Hollywood could distract him. Whether at the Lakers’ training facility or in pickup games at Venice Beach, Bryant remained intent on improving.

“I always tried to hold a basketball, watch basketball, think about basketball,” he told The Times in 1996. “People told me to get away from basketball, but I can’t. It’s in my blood.”

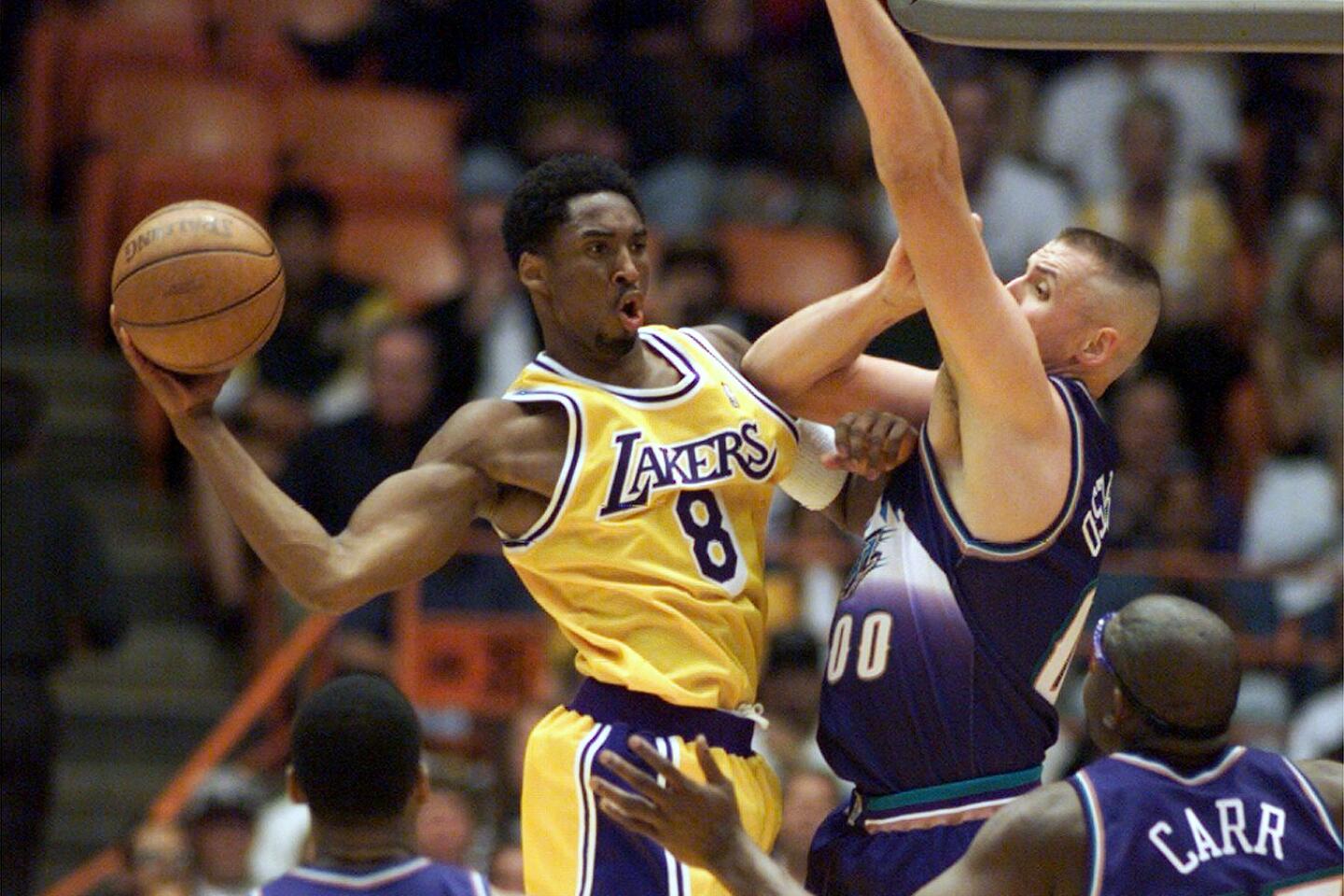

His first game with the Lakers was on Nov. 3, 1996, just after he turned 18. The stats from that loss to the Minnesota Timberwolves were nothing special: six minutes, a rebound, a blocked shot and a turnover.

::

A look back at the life of Kobe Bryant and his prolific career with the Los Angeles Lakers.

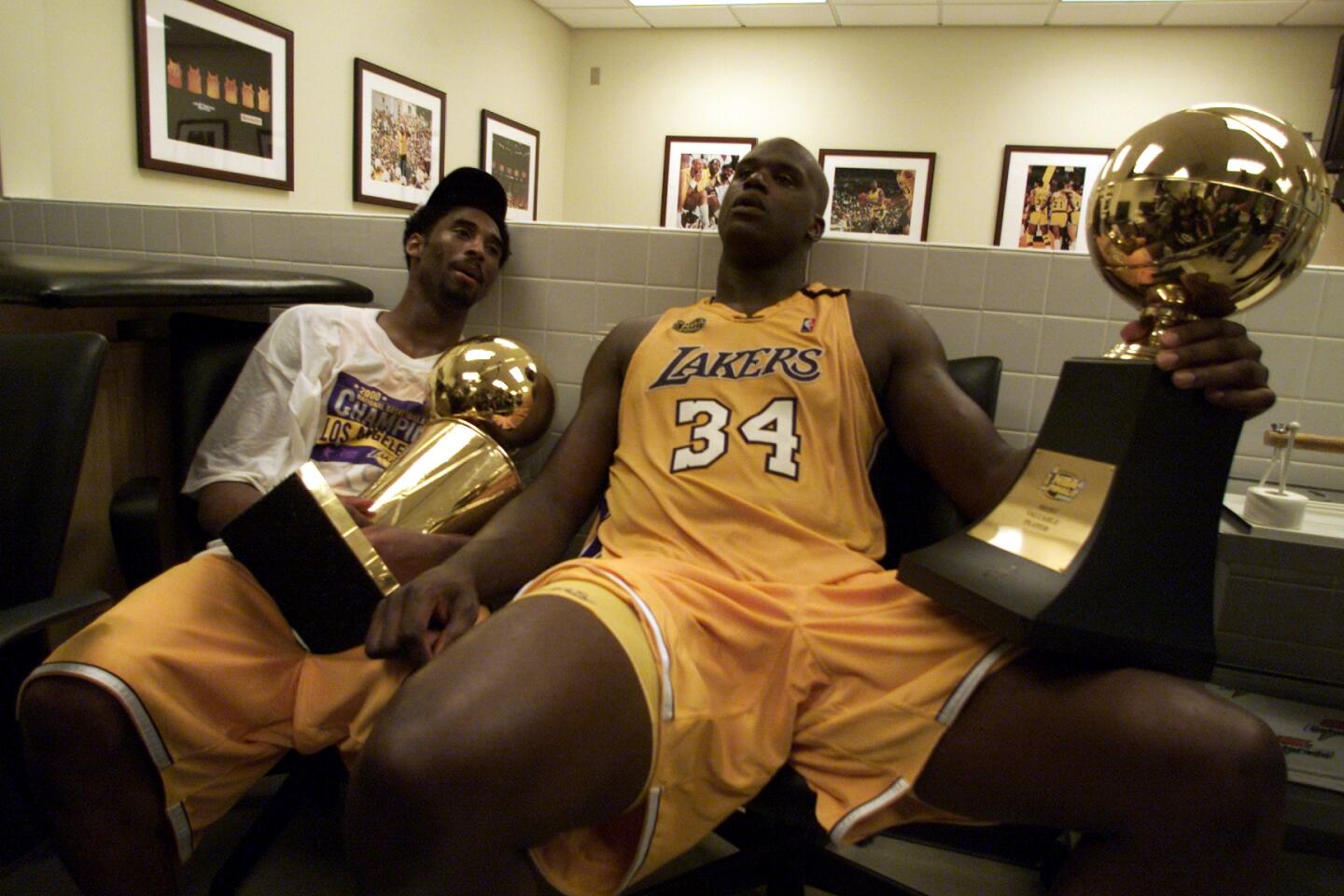

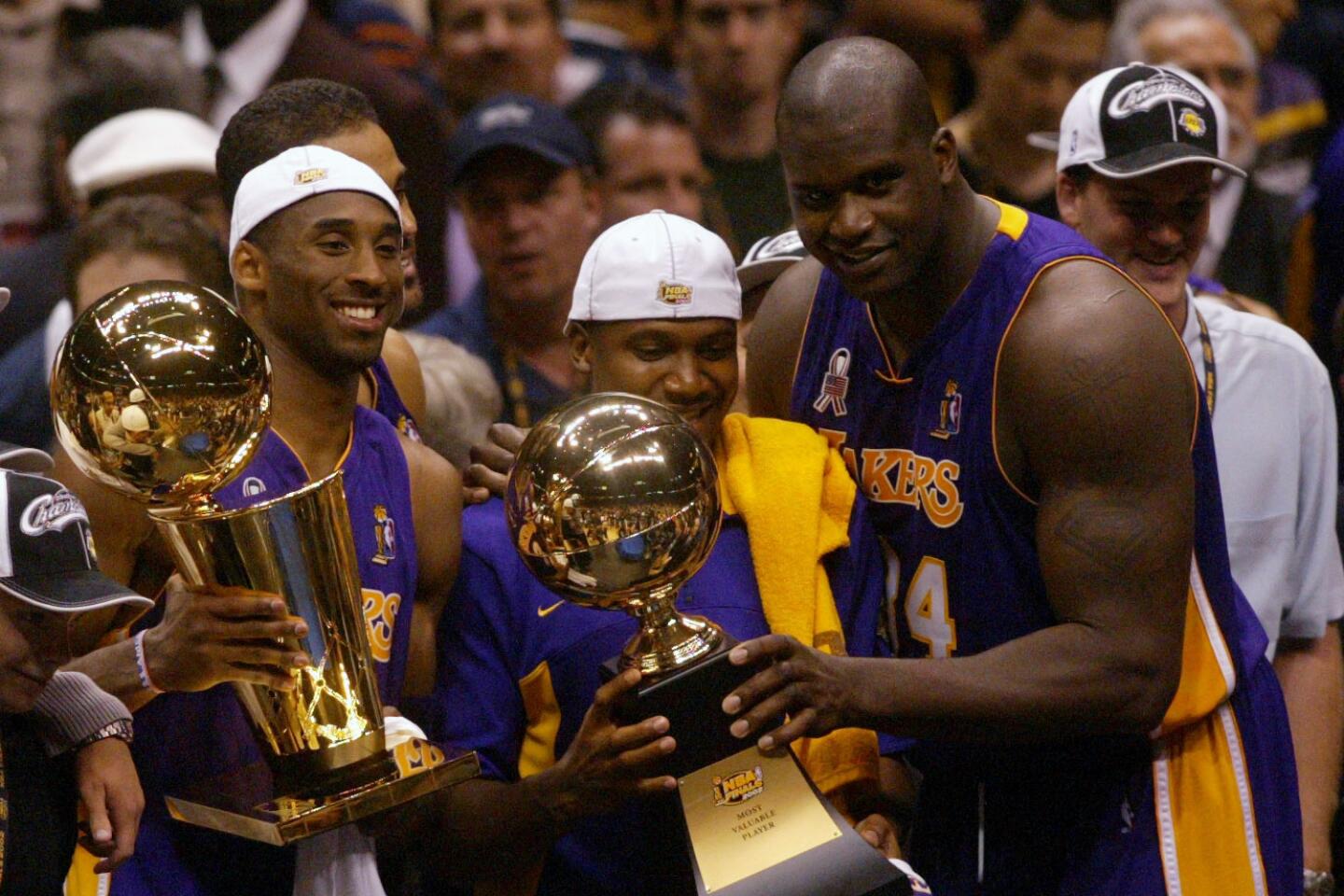

Fans could sense something familiar in the team’s new lineup — a frontcourt-backcourt twosome reminiscent of Johnson and Abdul-Jabbar. And like those former stars, Bryant and O’Neal would soon dominate the NBA.

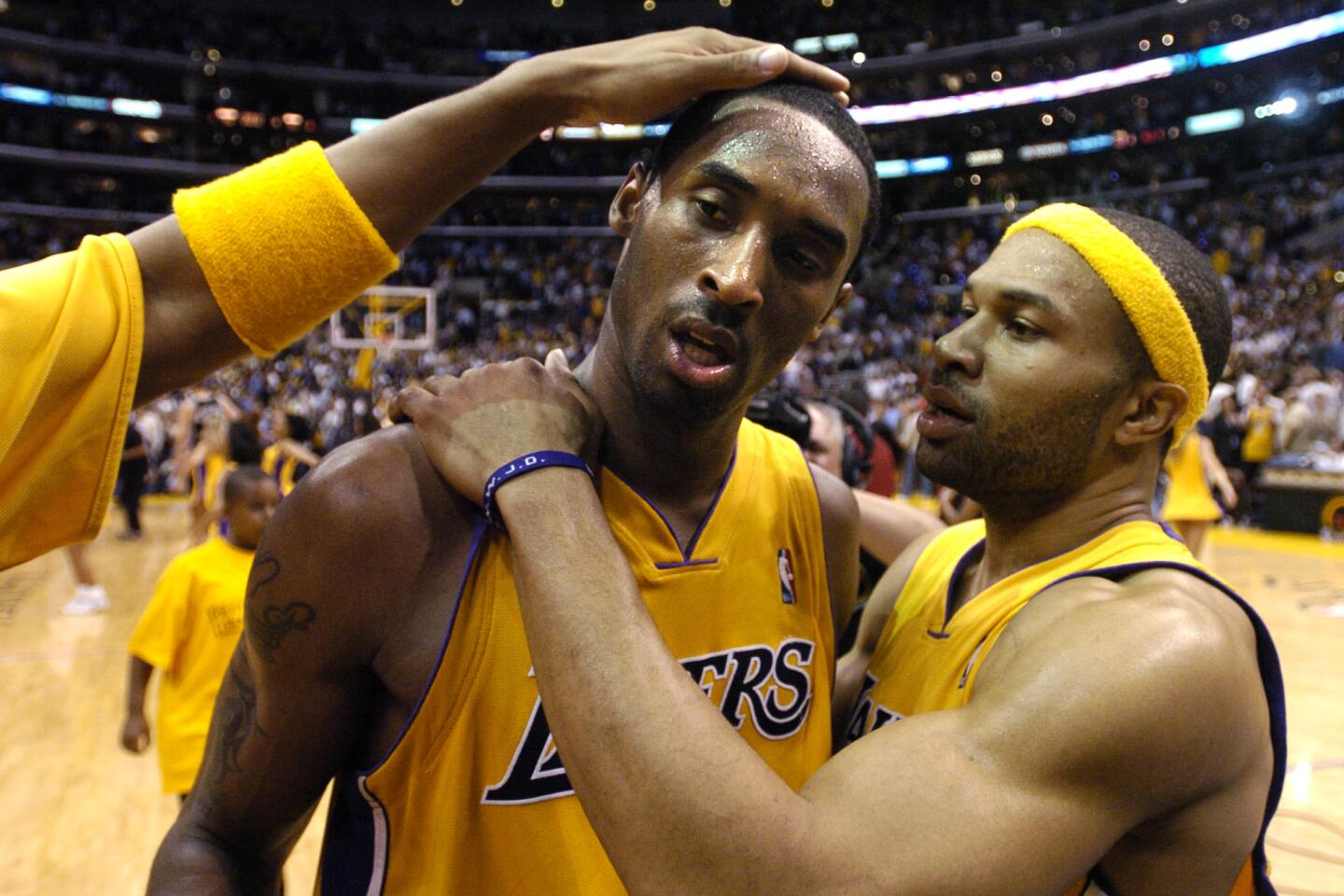

The Lakers won three consecutive championships through the early 2000s. But these complementary styles did not necessarily make for harmony in the locker room.

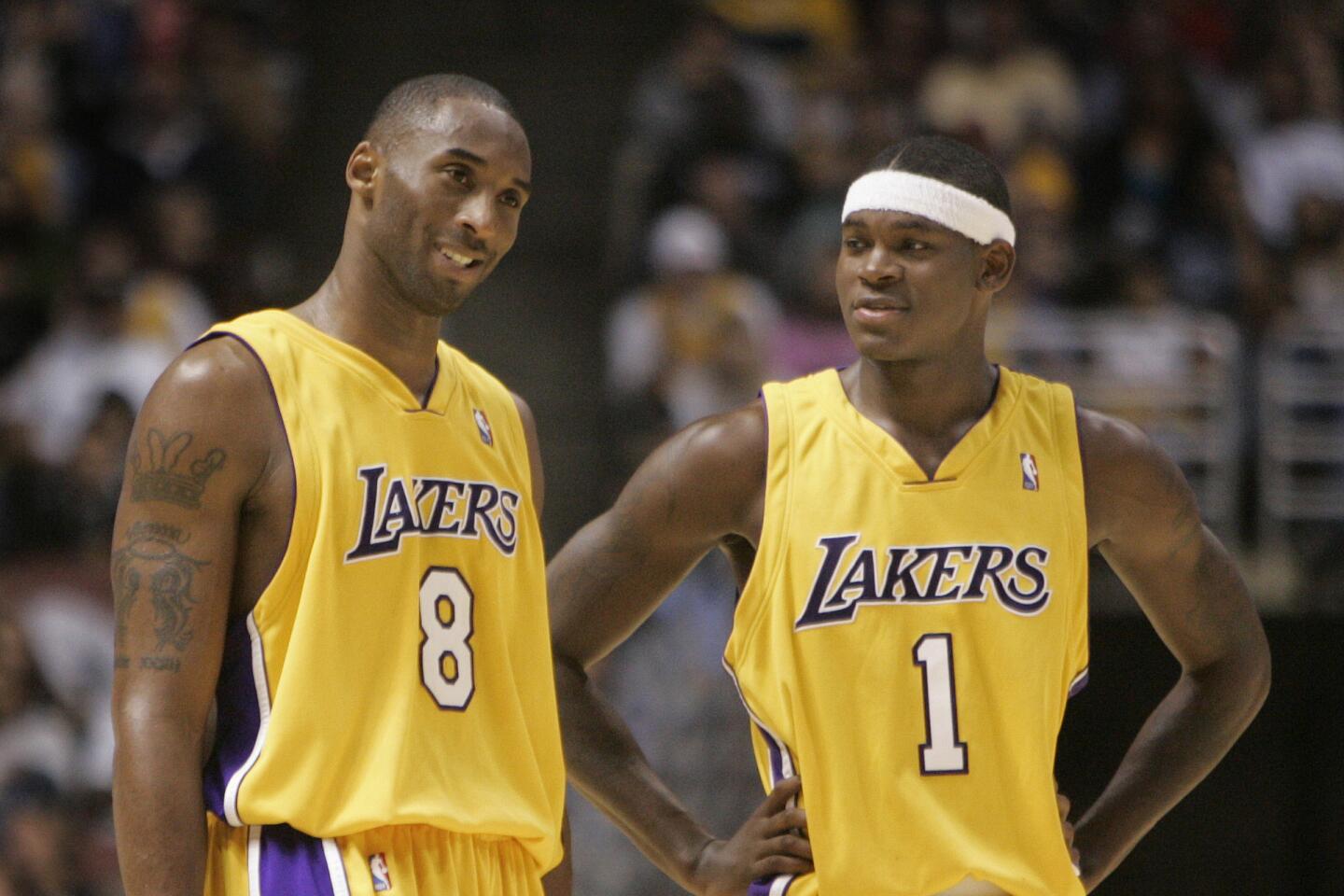

The 7-foot-1 O’Neal could exert his presence near the basket by sheer size and strength. Bryant represented a different type of game.

Among the best one-on-one players ever, he could beat opponents off the dribble, slashing to the basket for a highlight-reel dunk or pulling up for a medium-range jumper. As his career continued, he improved upon the shooting acumen that scouts had initially doubted, becoming a threat from long range.

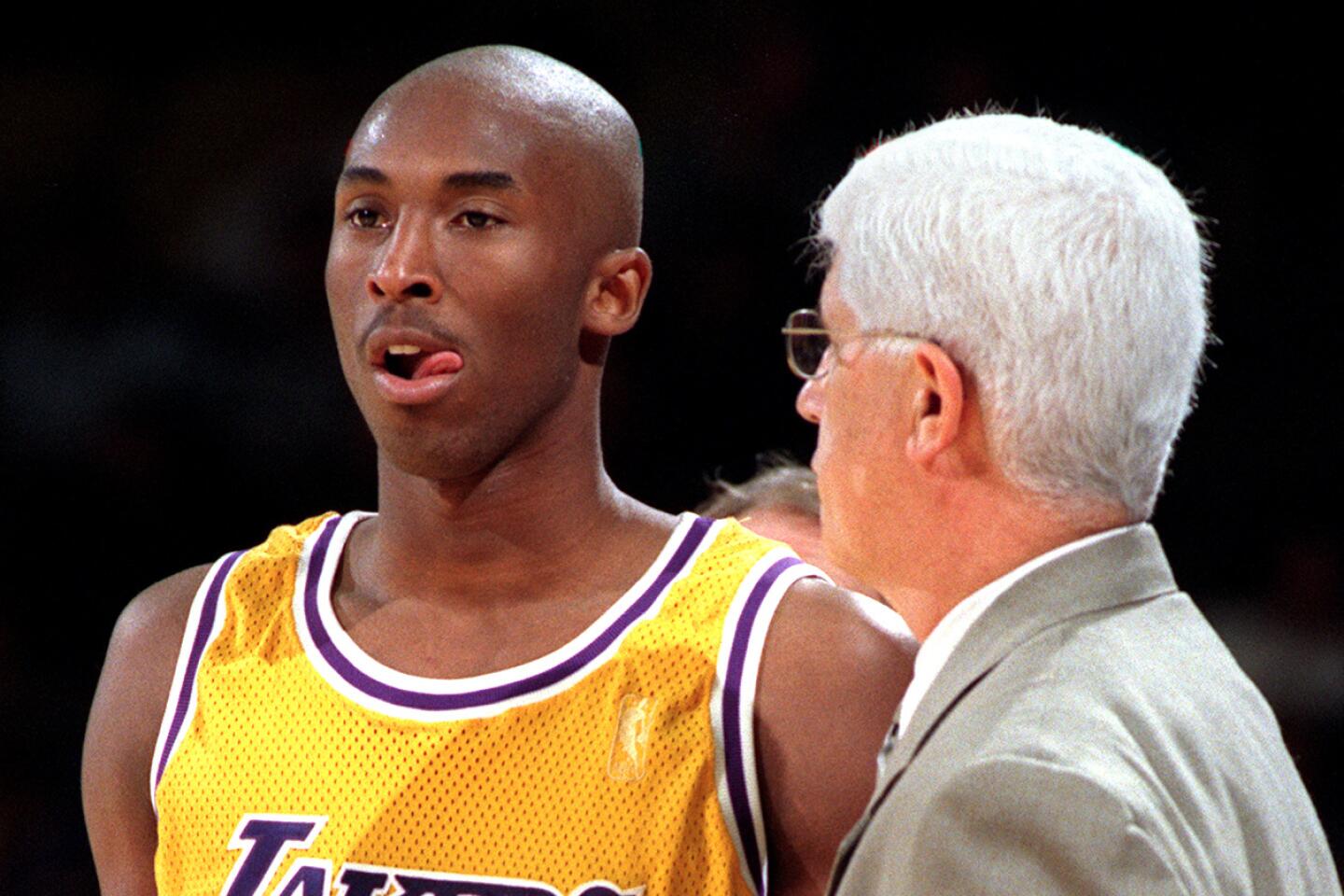

Juggling two emerging superstars, both with egos, coach Phil Jackson made O’Neal his first priority, forcing Bryant into something of a supporting role that did not sit well with the young guard.

Bryant’s curious background might also have set him apart from other players who grew up under very different conditions. He was known to keep to himself on the team bus, listening to music or talking on the phone. Some teammates thought of him as distant or even aloof.

By contrast, O’Neal was the big goofy kid, always laughing and joking, popular with the media.

A newspaper profile described them as prizefighters engaged in a war of wills, a standoff that threatened to divide one of the most talented basketball teams ever assembled. Two gifted athletes unwilling to surrender their egos, they were cast in Shakespearean terms, Bryant as Ariel against O’Neal as Caliban.

Los Angeles watched Kobe Bryant grow up. Los Angeles watched the Lakers legend stumble. And Los Angeles watched him get back up.

Jackson spoke about the players’ “emotional tussles” and the need for them to “corral their own personal interests.”

Off the court, Bryant was adding to his portfolio of sponsorships, reaping millions from deals with McDonald’s, Coca-Cola, Spalding and Nike.

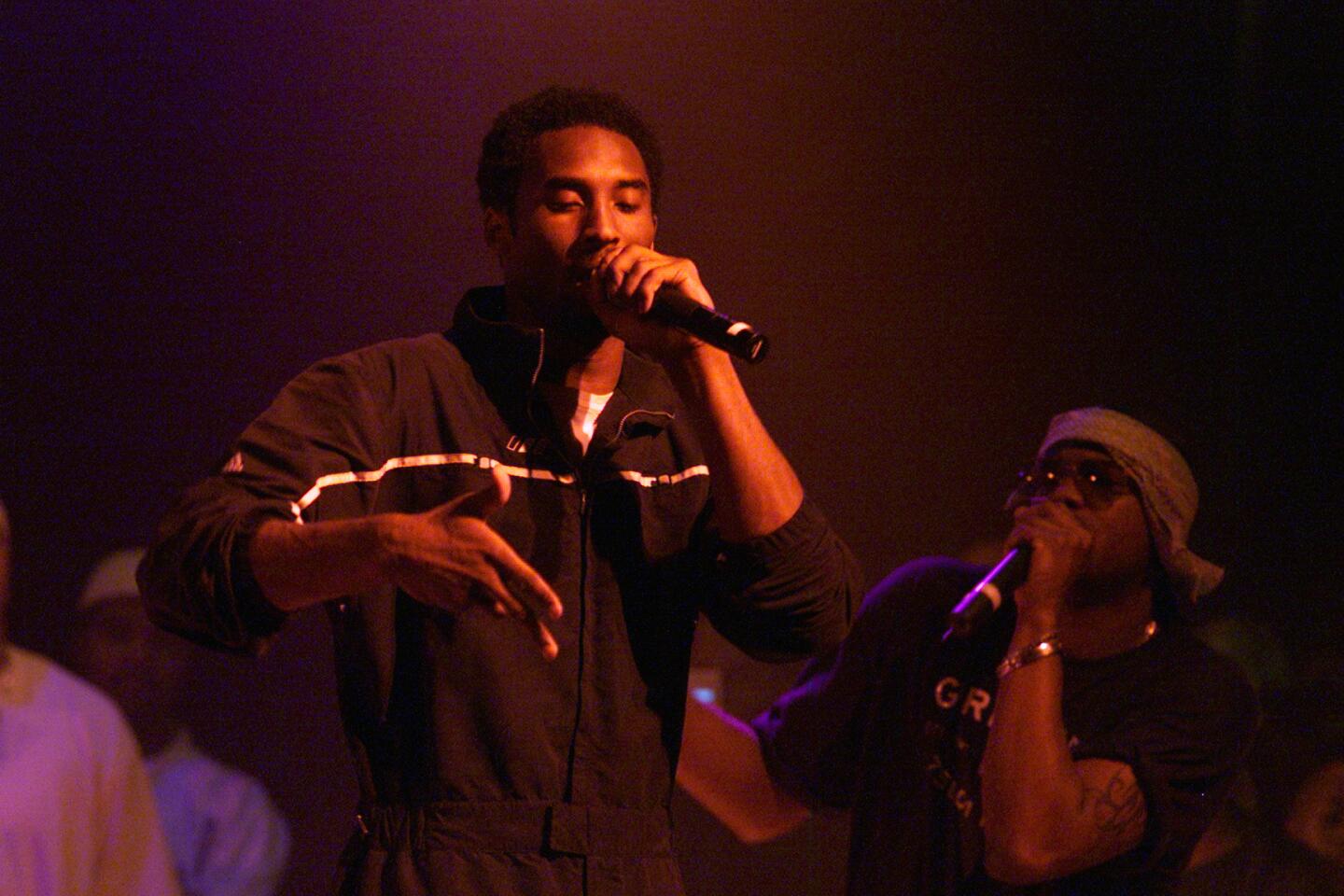

It was around this time that he met Vanessa Laine, a 17-year-old he saw in a video where she performed as a “gangsta siren in a metallic bikini and heavy black eyeliner.” Bryant called for her to appear in a rap album that he was recording.

When word spread that they were dating, news crews swarmed the Orange County high school she attended. He sent her roses and picked her up after class in his black Mercedes.

They announced their engagement four days after her 18th birthday.

::

The families had their doubts. He was black and she was Latina. He was close to his father, and she had scarcely known hers. He was raised in Europe and an affluent suburb of Philadelphia; she had grown up in a Garden Grove tract house.

Bryant and Vanessa were married in Dana Point in 2001. Neither his parents nor his sisters nor any of his teammates attended. Bryant would later acknowledge the engagement and marriage led to a two-year estrangement from his father.

When the Lakers won their second championship in Philadelphia in 2001, Kobe was spotted holding the trophy in the shower and crying. Some wondered if the conflict with O’Neal was taking its toll; Bryant would later say he was thinking about the rift in his family.

“It had been such an awful year for me, so hard,” he said. “I want a father. I want my father.”

Kobe Bryant enjoyed spending time with all his children and wanted to do everything he could to help his daughter Gianna play they game they loved.

Bryant took refuge in his relationship with Vanessa, as bodyguards accompanied them to Disneyland and got them seats at the local Cineplex after the lights went down. The couple bought a home in the Newport Beach community of Newport Coast, where they installed his “Star Wars” memorabilia and her Disney collectibles. For her 19th birthday, he bought her a Lamborghini with a special adapter so she wouldn’t have to drive a stick shift.

Their first daughter was named Natalia Diamante, in deference to Vanessa’s taste for diamonds.

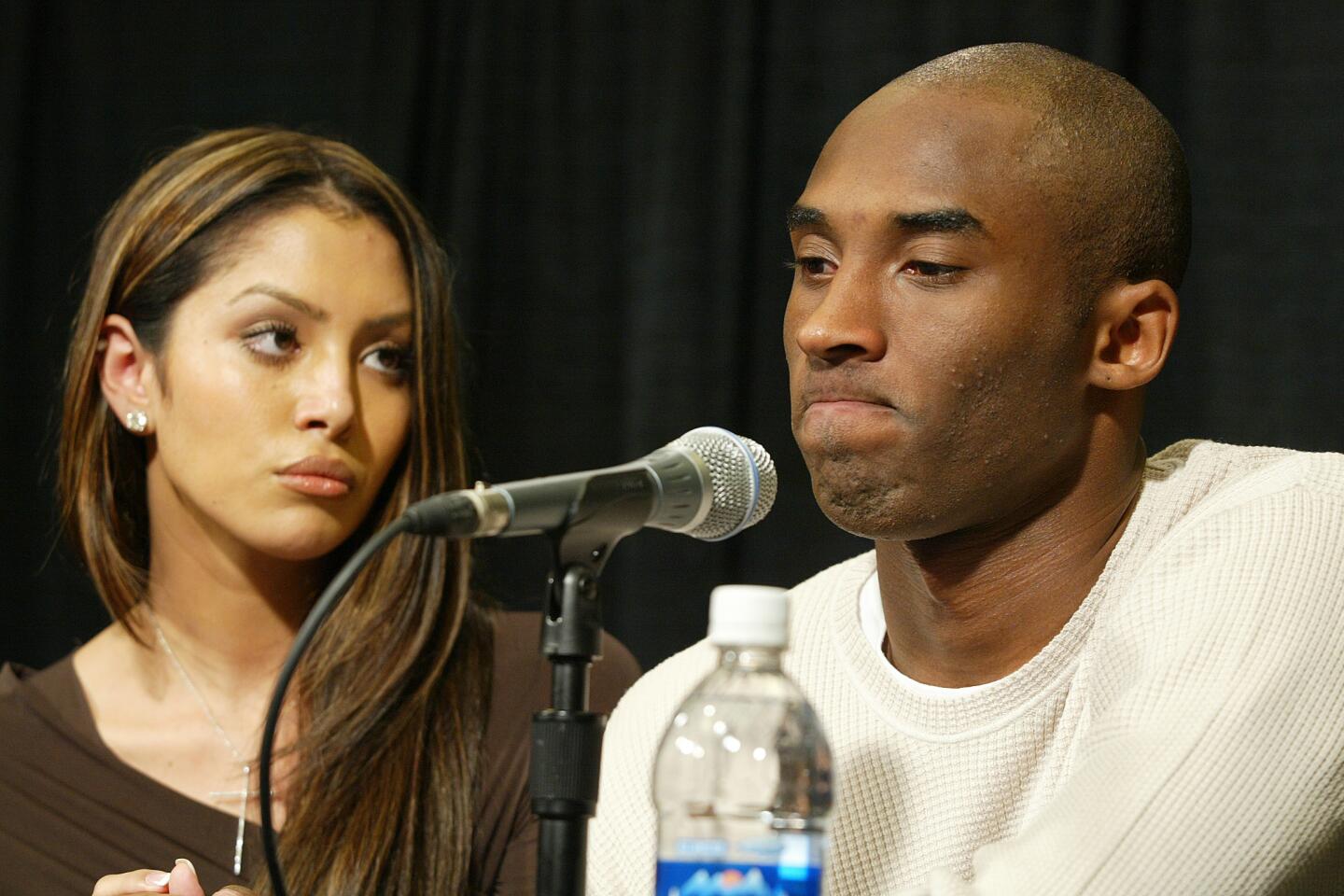

The life they led — part fairy tale and part extended family drama — would explode in the summer of 2003 when Bryant, visiting Colorado to rehab from a knee surgery, was accused of raping a 19-year-old hotel employee.

Flying back to L.A., he called a news conference at Staples Center and, with tears in his eyes and voice quavering, acknowledged having sex with the woman but insisted it was consensual. Vanessa was by his side as he spoke.

“I didn’t force her to do anything against her will,” he said. “I’m innocent. You know, I sit here in front of you guys, furious at myself, disgusted at myself for making the mistake of adultery.”

Prosecutors charged him with felony sexual assault, creating a media whirlwind fed by themes of sex, celebrity and race. Bryant’s attorney talked about a history of “black men being falsely accused of this crime by white women.”

The case was also marked by serious blunders, with officials mistakenly emailing transcripts from closed hearings to seven news organizations.

In September 2004, just days before the trial was to begin, his accuser decided not to go forward and the charges were dropped.

By then, some sponsors had severed their deals with Bryant, his reputation tarnished.

::

The years that followed were difficult.

Tabloids speculated about the Bryants seeking a divorce, which they denied. When a fan shouted at him from the stands of a game against the Clippers, she jumped up and got into a confrontation.

O’Neal would leave for the Miami Heat in 2004, helping that team to an NBA championship one season later, while the Lakers retooled their roster.

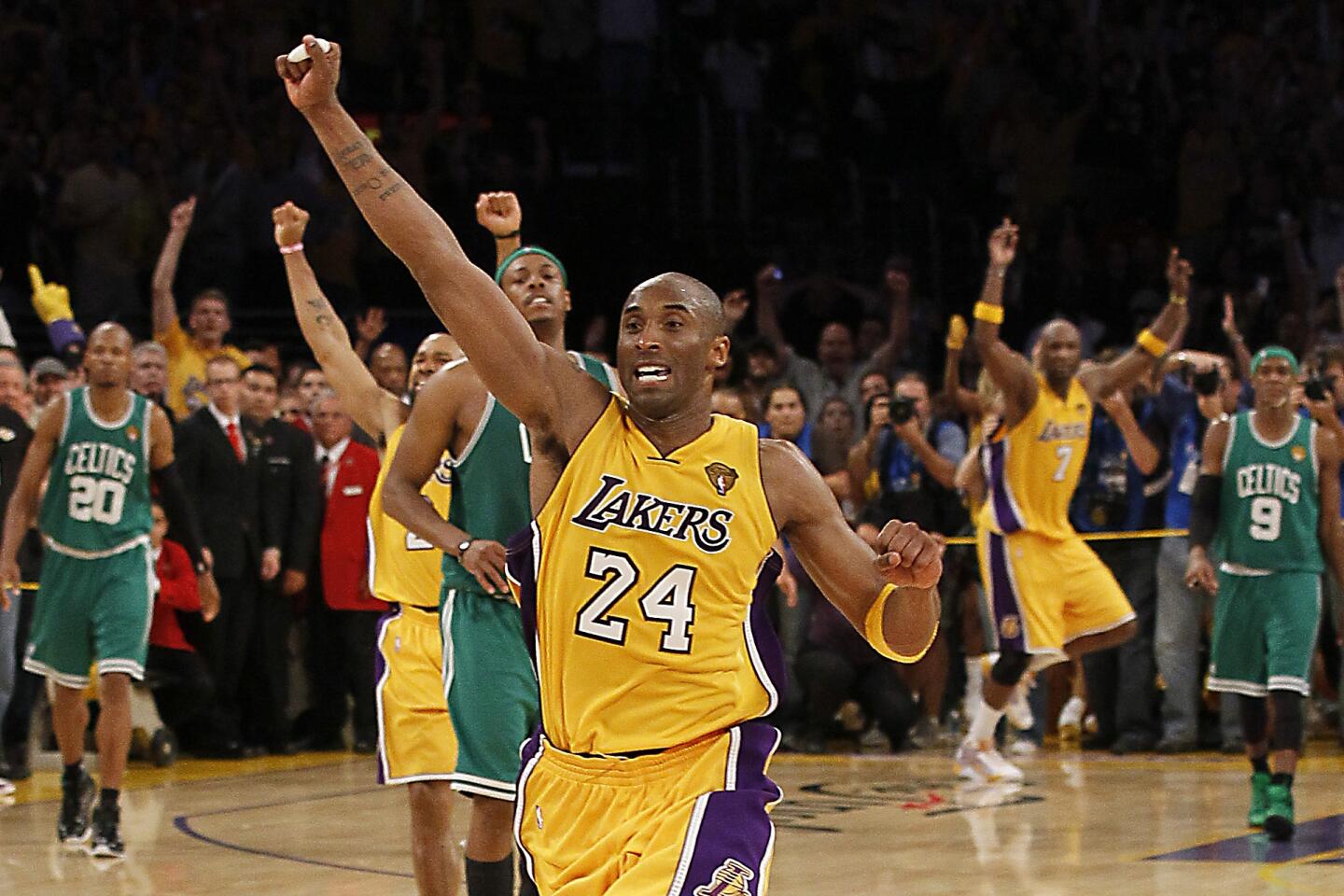

But Bryant was never the sort to shy from a challenge. Still paired with backcourt mate Derek Fisher, and surrounding by newcomers such as Pau Gasol and Lamar Odom, he led the team to back-to-back championships in 2008-09 and 2009-10.

By the time Bryant announced his retirement in November 2015, the Lakers had slipped back into mediocrity or worse.

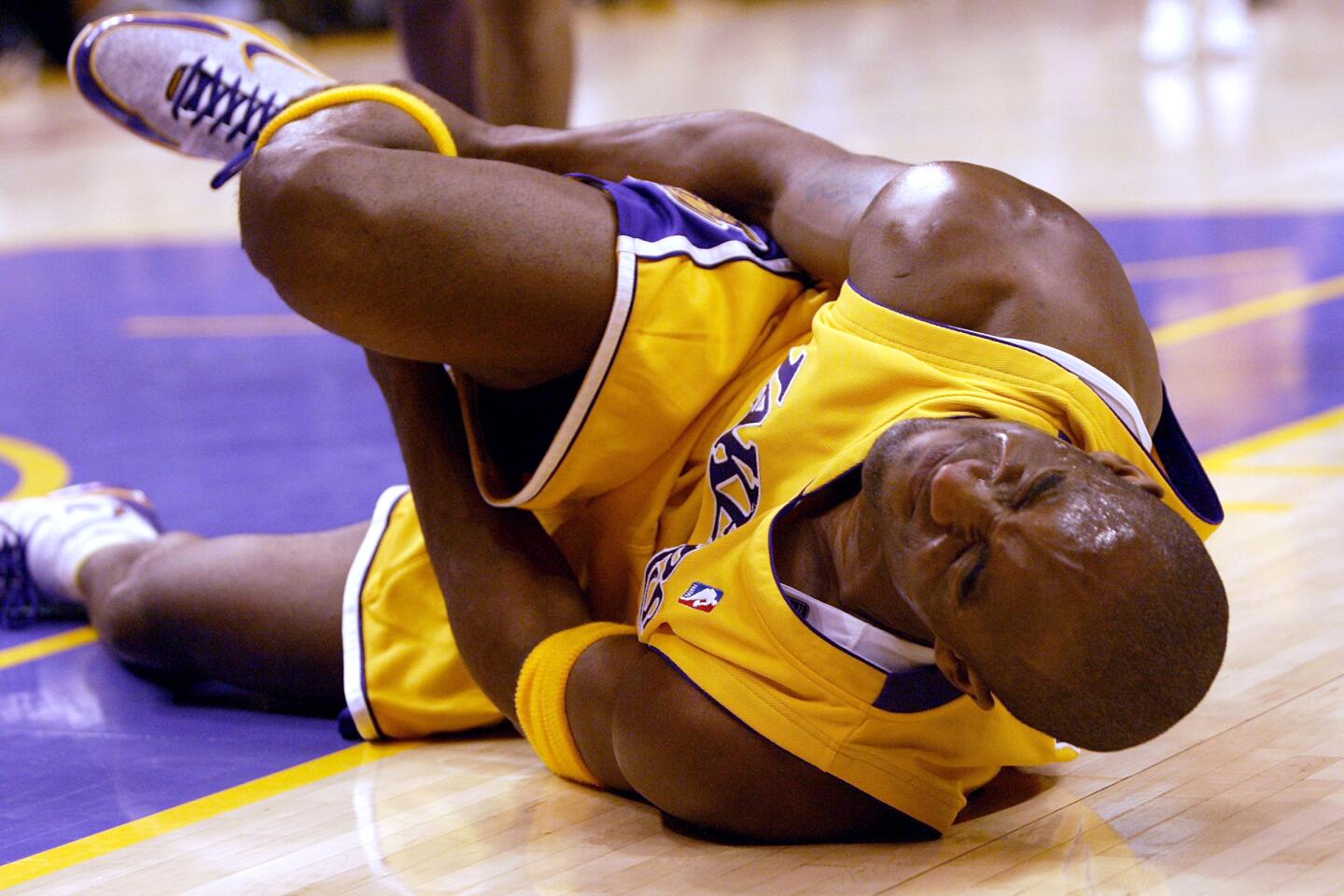

Bryant had talked about making a comeback, but he had been hit by injuries, including a ruptured Achilles tendon in 2013. A year later, he was already looking to his future.

“Twenty years is a long time, man,” he said in an interview with the New Yorker in 2014. “The challenge also has to shift to doing something that a majority of people think that us athletes can’t do, which is retire and be great at something else.”

He had just signed a two-year contract extension for nearly $50 million.

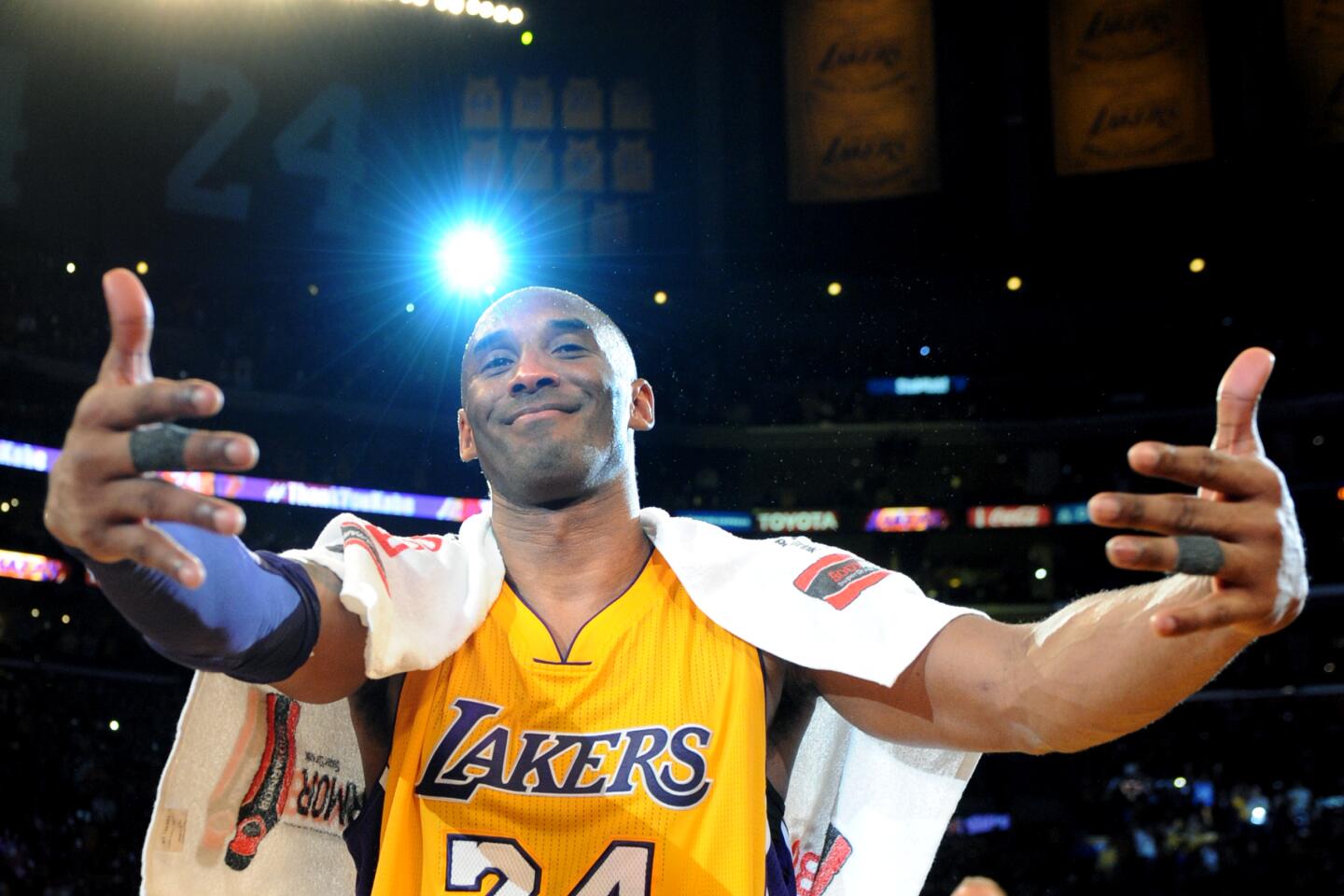

As his final season drew to a close, fans merely wanted a last chance to see him.

Tickets for his final game sold for as much as $27,500 on the secondary market. Rock guitarist Flea played the national anthem and the crowd included celebrities such as Snoop Dogg, Taylor Swift, Kanye West and Kim Kardashian.

“Kobe Bryant has never cheated the game,” Johnson said before tipoff. “He has never cheated us fans. He has played hurt and we have five championship banners to show for it. When you think about this town for the last 20 years, this man has been the biggest and greatest celebrity we’ve had…. He’s the greatest to wear the purple and gold.”

In the fourth quarter, as Bryant made shot after shot against the Utah Jazz, on his way to 60 points, the arena was filled with a steady, deafening cheer. Bryant picked up a microphone afterward to address the crowd.

“This has been absolutely beautiful,” he said. “I can’t believe it’s come to an end.”

Times staff writer Broderick Turner contributed to this report.

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.