Little Richard, flamboyant rocker who fused gospel fervor and R&B sexuality, dies at 87

- Share via

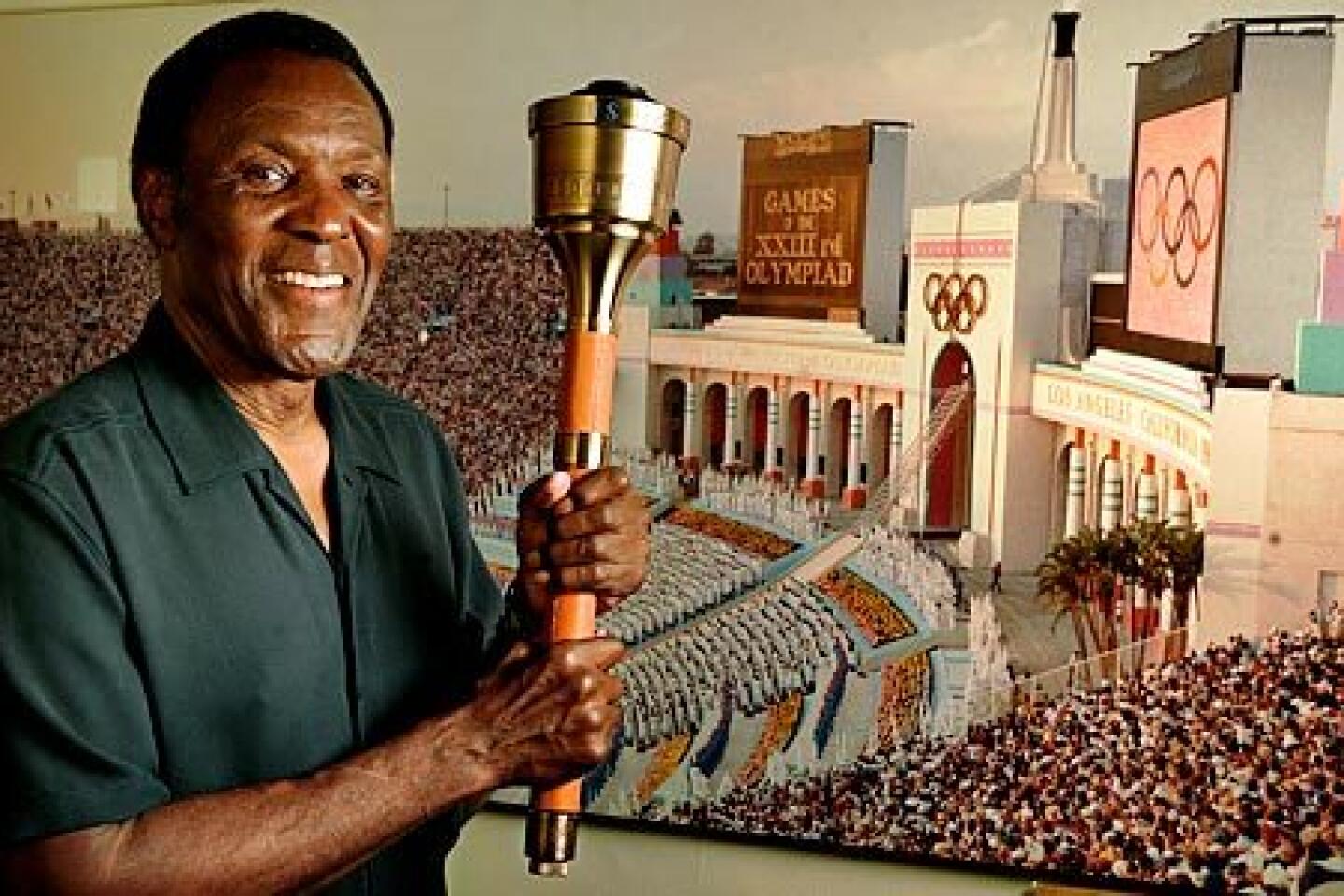

It was a monochrome world when Little Richard roared into the American spotlight, a flamboyant, piano-pounding showman who injected sheer abandon into rock ’n’ roll and carved out a path that would be followed by musicians and their fans for decades to come.

In hits such as “Tutti Frutti,” “Long Tall Sally” and “Good Golly, Miss Molly,” the singer pushed the limits of tempo and vocal intensity, creating frantic explosions of sonic confetti. His records entered a pure, primal realm that transcended verbal expression, embodied in his falsetto whoops and signature incantation: a-wop-bop-a-loo-bop-a-lop-bam-boom.

Though deeply torn between his religious yearnings and the temptations of rockdom, Richard nonetheless basked in his anointment as a founding father of early-day rock ‘n’ roll until the end.

Richard died Saturday at his family home in Tullahoma, Tenn., his son Danny Penniman said on the musician’s Facebook page. He was 87 and had been battling bone cancer.

Roy Horn, the dark-haired half of Siegfried & Roy, raised the white tigers and other animals in the duo’s extravagant shows that were one of the biggest draws on the Las Vegas Strip.

The Georgia native’s raucous sound fused gospel fervor and R&B sexuality into an enduring template, exerting a profound influence on the Beatles and many other legends to follow, including James Brown (who succeeded him in one of his early bands), Jimi Hendrix (one of his backup musicians in the mid-’60s) and Bruce Springsteen.

In addition, Richard’s sexual ambiguity and outrageous look — high pompadour, makeup, wild outfits — resonate through generations of pop’s gender rebels, including Mick Jagger, Elton John, David Bowie, Michael Jackson and Prince.

His songs (most of which bore his credit as a co-writer) were bawdy, but still relatively innocent next to the blues of the era, marked by a comical, slapstick energy. “I saw Uncle John / With bald-headed Sally / He saw Aunt Mary coming and he jumped back in the alley,” he sang at breakneck speed in “Long Tall Sally,” his first top 10 hit, in 1956.

Even so, his pansexual posture and onstage antics were enough to scandalize mainstream America — which only made him more appealing to the teenagers who were forming a new marketing category for the record business.

It was an audience open to performers regardless of race, and while black artists had occasionally cracked the pop charts in the past, it was now a whole new world, as Richard and other African American singers — Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Bo Diddley, Frankie Lymon, et al. — mingled with their white counterparts to create the polyglot vitality of late-’50s pop radio.

Richard’s exaggerated persona eventually evolved into caricature, obscuring his initial impact but helping him return repeatedly from obscurity in his later years, when he acted in films, appeared on TV game shows and in commercials and recorded a children’s album.

The self-proclaimed “architect of rock ’n’ roll” often complained that he didn’t get his due recognition or financial rewards, blaming racism, conspiracies, unfair contracts and the practice of having more conventional, white singers such as Pat Boone record his songs in watered-down versions that outsold the originals.

“God bless Elvis — he and I were very close friends — but I didn’t get the credit I deserved,” Richard said in a 2004 interview with the Dallas Morning News. “The industry back then didn’t allow me to get the credit, because I was black and the kids who were buying my records were white.”

But in a remarkably concentrated two-year output beginning in early 1956, he formed an honored foundation of rock. Richard was one of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s inaugural inductees in 1986, and he received the Recording Academy’s lifetime achievement award in 1993.

“It was an era for kids to get crazy, man, crazy, to quote the Bill Haley record, and Richard was the craziest of them all,” musician and music historian Billy Vera told The Times. “He allowed kids the freedom to get wild and feel wild and give vent to those feelings.

“It was just, ‘Wow, look at him, look at him, wow, look what he’s doing, he’s screaming, he fell on the floor, he’s jumping up on the piano, just listen to that crazy voice,’” said Vera, who oversaw a 1989 box set of Little Richard’s seminal recordings. “Nobody was as crazed as Richard.”

Richard Wayne Penniman was born Dec. 5, 1932, in Macon, Ga., the third of his family’s 12 children. His father supplemented his earnings as a bricklayer by dealing in bootleg liquor, and the Penniman family enjoyed a comfortable standard of living.

Richard was saddled with some physical quirks — one leg longer than the other, a large head, one enlarged eye — but they didn’t inhibit him. He was outgoing and mischievous, hungry for attention, fond of pulling outlandish pranks and singing in public.

His was a religious family in a musical neighborhood, and he sampled different denominations, including Baptist and Pentecostal. He performed church music with a children’s vocal quartet, the Tiny Tots, and later with a group of his siblings.

As a teenager, according to his own account in Charles White’s 1984 book, “The Life and Times of Little Richard,” he became sexually active with both men and women, though over the years he variously modified his story and renounced and/or denied his homosexuality.

His enthusiasm for music and performing coincided with his lack of interest in school, and he left home to travel with minstrel and medicine shows, consorting with drag performers and musicians from big bands and blues groups.

He admired gospel artists such as Clara Ward, Brother Joe May and especially Mahalia Jackson, as well as blues singers such as Ruth Brown. In Atlanta, he studied bluesman Billy Wright, a flashy showman who favored a high hairdo and loud suits.

Andre Harrell, the Uptown Records founder who shaped the sound of hip-hop and R&B in the late ’80s and ’90s, has died at 59.

Wright helped steer the young singer to RCA Records, and the blues songs he recorded in 1951 yielded a regional hit, “Every Hour.” When his father was murdered in 1952, Richard became the family’s breadwinner, washing dishes at the Macon bus station while prospering on the regional club circuit with his new band, the Upsetters.

In the mid-’50s he met R&B star Lloyd Price, who advised him to contact his label, Specialty Records. Richard sent a demo tape to the Los Angeles company, whose owner, Art Rupe, was looking for someone to compete with Atlantic Records’ new sensation Ray Charles.

Sensing some potential in the urgent voice on the crude tape, Rupe signed Little Richard and dispatched producer Robert “Bumps” Blackwell to record him in New Orleans in September 1955, with the cream of the city’s studio players, including saxophonist Lee Allen and drummer Earl Palmer.

As the first session proceeded, Blackwell was disappointed with Richard’s inhibited performance. They took a break for lunch at the nearby Dew Drop Inn, where Richard had frequently played in the past, and he decided to do an impromptu performance.

“He’s on stage reckoning to show Lee Allen his piano style,” Blackwell recalled in the Charles White book. “So WOW! He gets going. He hits that piano, didididididididididi ... and starts to sing ‘Awop-bop-a-Loo-Mop a-good Goddam — Tutti Frutti, good booty...,’ I said, ‘Wow! That’s what I want from you, Richard. That’s a hit!’”

Before they recorded it, though, they assigned a young songwriter, Dorothy LaBostrie, to revamp the sexually explicit lyrics. She arrived at the studio 15 minutes before the end of the session, and three takes later, they had their hit. “Tutti Frutti” reached No. 2 on the national R&B chart and No. 17 on the pop chart in early 1956.

The follow-up, “Long Tall Sally,” made the top 10, and was joined there later by “Jenny Jenny,” “Keep a Knockin’ ” and “Good Golly, Miss Molly.” Richard’s other notable singles were “Rip It Up,” “Slippin’ and Slidin’ (Peepin’ and Hidin’)” and “Lucille.”

Richard capitalized on his flurry of hits, playing countless concerts and appearing in a couple of quickie rock ’n’ roll movies, as well as the Jayne Mansfield comedy “The Girl Can’t Help It” (his title song was another hit). He moved to Los Angeles, buying an elegant house next door to Joe Louis in the Mid-City area and bringing his mother out west.

And as suddenly as he had arrived, he walked away. The latent conflict between his show business lifestyle and his ingrained religious beliefs came to a head during a 1957 tour of Australia. Richard later cited an in-flight vision in which angels supported his stricken airplane, as well as the launching of the Russian satellite Sputnik, as signs that inspired his rebirth.

He quit music with 10 days left on the tour and, back in California, joined the Church of God of the Ten Commandments. He traveled and preached, and enrolled at Oakwood College in Alabama to study for the ministry. At the urging of church colleagues, he looked for a wife, and married Ernestine Campbell in 1959. They were divorced several years later.

Richard began recording religious music, and in 1962 he took an offer to tour England singing gospel songs. But when he saw the audience response to Sam Cooke, one of his opening acts, he dusted off the old hits. Little Richard was back — though he later called it a relapse.

Another of his opening acts on that trip was the Beatles, still unknown and thrilled to meet the master. Richard recalled teaching Paul McCartney how to execute the falsetto whoop during a subsequent sojourn in Hamburg, Germany. It would resurface as a key hook in the foursome’s “I Saw Her Standing There” and “She Loves You.”

The Beatles also paid homage by recording “Long Tall Sally” and Richard’s arrangement of “Kansas City,” but while they and their contemporaries used his model as a steppingstone to stardom, Richard recorded gospel and soul music and toiled as a touring rock ’n’ roll act through the ’60s. He eventually worked his way up to prominent bookings, including Las Vegas stages and the Fillmore East in New York.

There were a couple of minor hits in the early ’70s, but Richard had become ensnared in a life of drugs, drink and hedonism. A string of incidents in the mid-’70s — including his brother Tony’s death from a heart attack and a drug-related threat on his life by an old friend, singer Larry Williams — prompted him to leave music a second time.

He again renounced rock ’n’ roll as “demonic” and turned to religion, moving to Riverside to shake his drug habit. He preached for the Universal Remnant Church of God and sold copies of the Black Heritage Bible.

He reemerged in the 1980s, acting on television (“Miami Vice”) and in film (“Down and Out in Beverly Hills”), and returning to secular music. He recorded a children’s album for Disney, sang the theme for the “Magic School Bus” TV series, and played at President Clinton’s inaugural in 1993.

More recently, he gave the keynote address at the 2004 South by Southwest music festival in Austin, Texas. His latest recordings appeared on a tribute album to Johnny Cash in 2002 and Jerry Lee Lewis’ 2008 collection of duets.

He was still performing occasionally as of 2009, having reconciled his sacred mission and secular passion, and promised to return to the stage following hip surgery late in the year.

“I believe there is good and bad in everything,” he said in the mid-’80s. “I believe some rock ’n’ roll music is really bad, but I believe that there is some not as bad. I believe that if the message is positive and elevating, and wholesome and uplifting, this makes you think clearly. If it’s not, then it is not good even in gospel.”

Cromelin is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.