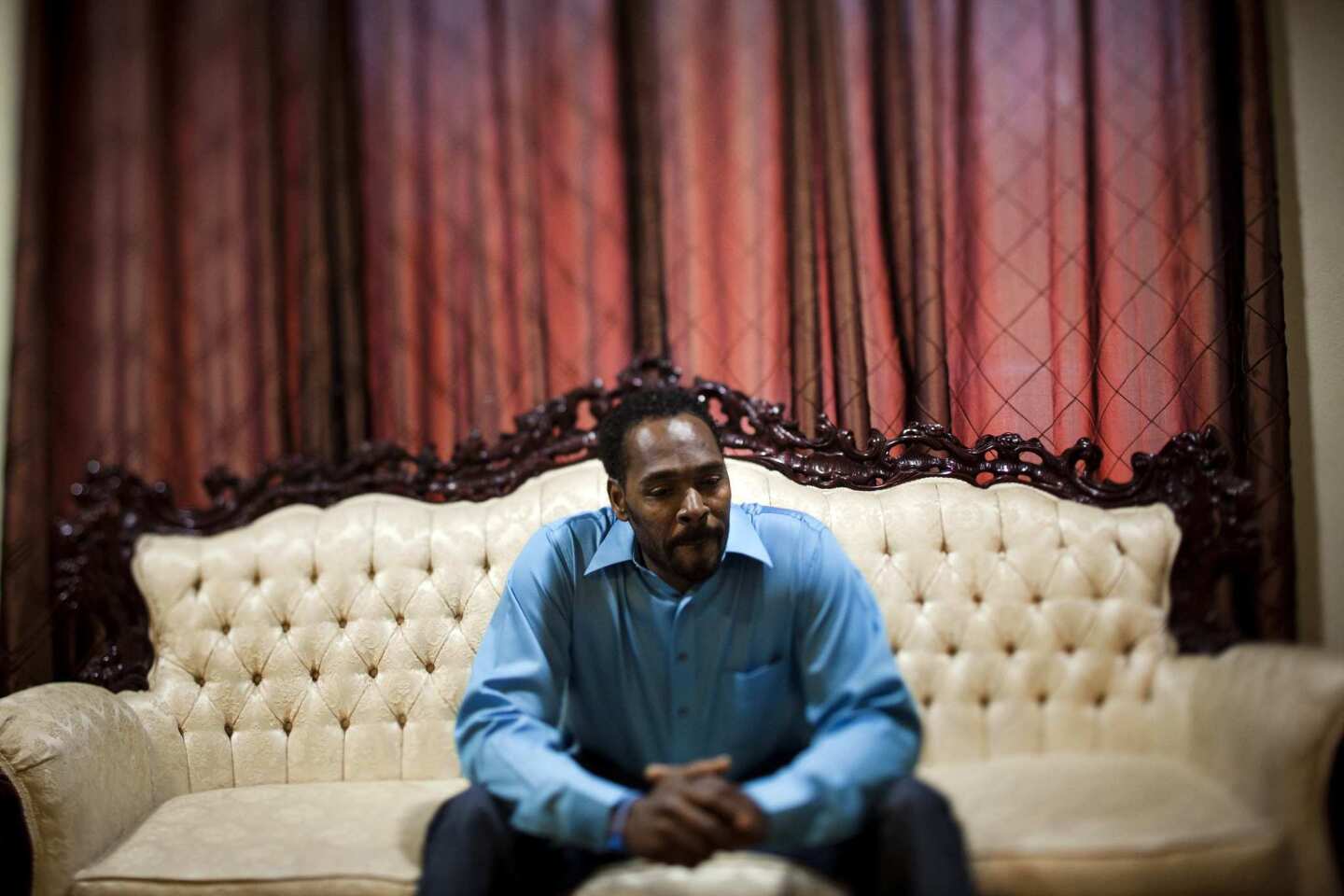

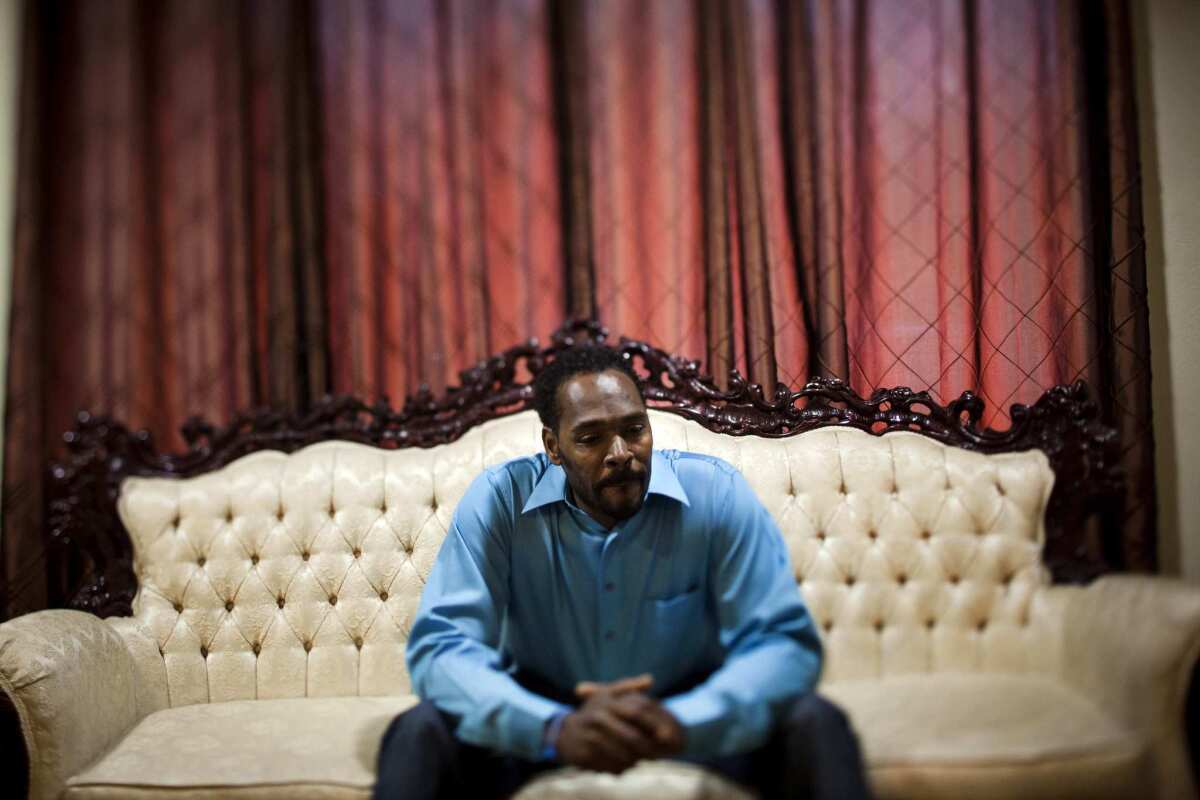

The past still grips Rodney King

- Share via

Rodney King holds in his scarred hands a fishhook and a bag full of big white worms. He crouches on a dock at the edge of a lake on the outskirts of Ontario. It is early, and the sun is bright, the air quiet.

“I got these old fatties from my backyard, and they’re gonna be good luck,” he says, scooping one of the wriggling creatures from the bag. “They actually look like big ol’ maggots. Just gotta be careful: They bite.”

He spears the worm with the hook. The worm flails and then goes limp. King stands, tension draining from his face. He raises his fishing pole and casts. “I needed this,” he says. “I really needed this.”

It has been 20 years this month since rioting brought Los Angeles to its knees. A jury had acquitted four police officers in the beating of King, unleashing an onslaught of pent-up anger. There were 54 riot-related deaths and nearly $1 billion in property damage as the seams of the city blew apart.

King remembers. He rubs his right cheek, numb since the beating, and describes what it was like to be struck by batons, stung by Tasers.

“It felt,” he says, “like I was an inch from death.”

Later he confides that he is at peace with what happened to him.

“I would change a few things, but not that much,” he says. “Yes, I would go through that night, yes I would. I said once that I wouldn’t, but that’s not true. It changed things. It made the world a better place.”

He is 47 now — jobless and virtually broke. Gone is the settlement money he got after suing the city for violating his civil rights. All $3.8 million of it. Huge chunks went to the lawyers, he says, some to family members, some he simply wasted.

The settlement did provide a down payment on the inconspicuous rambler that is his home in Rialto. He says he cobbles together mortgage payments. Every so often he gets hired to pour concrete at a construction site. He has earned small paydays fighting in celebrity boxing matches. He received an advance — less than six figures, he says, but significant nonetheless — for allowing his story to be told in a book set to go on sale Tuesday: “The Riot Within: My Journey from Rebellion to Redemption.”

Rodney King redeemed?

He inhabits a world stocked with heartache and struggle. He calls himself a recovering addict but has not stopped drinking and possesses a doctor’s clearance for medical marijuana. He says he is happy and hopeful, content enough now to forgive the officers who beat him. But he tenses when they are mentioned and admits to being burdened by the weight of his name. He suffers nightmares, flashbacks and raw nerves that echo the symptoms of a shellshocked survivor of war.

On the dock, he gazes out at the smooth water. Fishing is healing. It calms him. Once his therapy was the ocean and surfing, until he was frightened one day by a school of dolphins that he mistook for sharks.

“I sometimes feel like I’m caught in a vise. Some people feel like I’m some kind of hero,” he says of the beating. “Others hate me. They say I deserved it. Other people, I can hear them mocking me for when I called for an end to the destruction, like I’m a fool for believing in peace.”

L.A. RIOTS: Reader stories | Share your memory

Rialto is a working-class suburb 50 miles east of the Pasadena foothills where King grew up. His home has a tattered look and, at least temporarily, a blue-green tarp for a back fence.

“The neighbors were looking through the holes in the old fence, so I tore it down,” he says. “They were trying to see Rodney King.”

Near the tarp is a small pool. Before he became a household name, King was a construction worker with a union card. He set the stone surrounding the pool. In black tile, he inscribed two dates: 3/3/91, the night he suffered over 50 blows from police batons, and 4/29/92, the night the rioting began.

Yes, I would go through that night, yes I would. I said once that I wouldn’t, but that’s not true. It changed things. It made the world a better place.

— Rodney King

King, the father of three grown daughters, is engaged to be married a third time.

Problem is, he can’t let go of the past.

On his walls, or stacked forlornly on the carpet, are photographs, paintings and newspaper and magazine clippings that tell how the police pounded him; how four officers were charged in state court but not convicted; how the city erupted in rioting, and how two of the officers, both white, were subsequently found guilty in federal court of violating King’s civil rights.

King’s eyes settle on pictures of those two officers, Stacey Koon and Laurence Powell. Each was sentenced to 30 months in prison.

“Man, that’s Koon right there,” he says with a visible shudder. “I’m just glad I survived what he did to me.”

Tall and broad-shouldered, King has a goatee and a short Afro that obscure some of the scars. He walks with a limp. He is polite but often seems timid and unsure. Sometimes he is insightful, other times boastful, but there are moments when he appears to drift.

That’s from the beating, he says. Brain damage.

His drinking and drugging and a few jarring traffic accidents hardly helped.

“There was the time my car went off the road and came to a stop on a tree,” he says, referring to a 2003 crash. Blood tests revealed PCP in his system.

“PCP ain’t no joke,” says King, who was ordered to rehab and spent a few weeks in jail. “That stuff really got its hooks into me for, oh, I think about a year.”

Some things unfailingly hold his attention. One is a large photograph above his fireplace. It is King, in a blue suit and a paisley tie, looking out at a pack of reporters.

“That’s me saying those words people still talk about,” he mutters. He says them, under his breath. “Can we all get along?”

Looking at these artifacts, he says, gives him an oddly detached sensation. A part of him cannot believe he is that man.

Yet he hangs on to all of it.

“That is my history, part of my history, part of me surviving,” he says.

As to why he wouldn’t change what happened that night, he has a theory. True, the beating and the first trial led to deadly violence. It fills him with guilt. How can he not feel responsible for what some still call “the Rodney King riots”? Yet good came of it. The convictions of Koon and Powell, he says, the moral weight that pushed his call to “get along” deep into the public consciousness — these things helped change the world.

“A lot of people would have never had [a chance to succeed] if I had not survived that beating,” he says.

“Obama? Obama, he wouldn’t have been in office without what happened to me and a lot of black people before me. He would never have been in that situation, no doubt in my mind. He would get there eventually, but it would have been a lot longer. So I am glad for what I went through. It opened the doors for a lot of people....”

When he was 2, King’s family moved from Sacramento to Altadena, at the base of the San Gabriel Mountains. Los Angeles, particularly South L.A., tough and dangerous, seemed a world away.

“He’s not now and never has been a real city guy, with that kind of sophistication,” says his cousin, Ontresicia Averette.

King’s parents cleaned offices and homes for a living. His father, Ronald, known in the neighborhood as “Kingfish,” was a hard-edged alcoholic who, before dying in his early 40s from pneumonia, heaped physical abuse on his son.

“Maybe those whuppings prepared me for Koon,” King says.

In junior high, King began drinking. As an adult, he was no angel. In 1989, he pleaded guilty to robbing a market in Monterey Park; the owner accused King of attacking him with a tire iron. King was given a two-year sentence.

The night of the beating, he hadn’t been out of jail very long. He had spent the evening drinking and watching TV with friends. Around midnight, he was caught speeding and led police on a chase that ended in Lake View Terrace. A test showed that King’s blood-alcohol level was slightly below the legal limit. The test was taken five hours after he’d been in custody, however, warranting estimates that it had been well above the legal limit while he was at the wheel.

Growing up, he had leaned heavily on his mother, Odessa, a devout Jehovah’s Witness. Her vision was both idealistic and apocalyptic: Yes, the world would end one day, possibly soon. But it would be replaced by a better one, where people of all races come together, sharing peace. King was never a full follower of his mother’s faith; he was too tied to booze and women. But her beliefs contributed to his hopeful — others call it naive — understanding of life.

That could explain why, when the four accused officers were acquitted, King holed up in his bedroom with a bottle of brandy and wept.

Even now, as he remembers, his jaw tightens.

He hasn’t talked about this much, but when the rioting began shortly after the verdict, he put on a wig of dreadlocks so he would not be recognized and drove toward the angry heart of the city.

“I couldn’t believe what I was seeing,” he says. “Mayhem, people everywhere, pissed off, looting, burning. Gunshots. I turned back and went home. I looked at all of that and I thought to the way I was raised, with good morals from my mother, even though I didn’t always follow them.

“I said to myself, ‘That is not who I am, all this hate. I am not that guy. This does not represent me or my family, killing people over this. No, sir, that is not the way I was raised by my mother.’ I began to realize that I had to say something to the people, had to try to get them to stop.”

So, on the third day of the rioting, he pleaded on television: “People, I just want to say, you know, can we all get along? Can we get along?”

During the first decade after the riots, King started an unsuccessful hip-hop recording company, had a series of tempestuous romances and steadily ran into trouble.

Over the last 20 years, he has had repeated contact with law enforcement. He long ago stopped keeping track of his arrests for crimes such as driving under the influence and domestic assault.

“Eleven times?” he wonders. “Twelve?”

“Man, all this crap I put myself through, yeah it’s embarrassing,” says King, who pushed back into public view in 2008, when he joined the reality show “Celebrity Rehab With Dr. Drew.”

“For a long time, sure, I was letting the pressure of being Rodney King get to me. It ain’t easy. Even now, I walk into a place wondering what people are thinking. Do they know who I am? What do they think about what happened? Do they blame me for all those people who died?”

His latest trouble came last summer. He was driving his beaten 1994 Mitsubishi Eclipse in Moreno Valley when a pair of Riverside County sheriff’s deputies pulled him over. They said he was swerving and had nearly hit another car. According to the official report, King was compliant and repeatedly replied, “Yes, Sarge” to one of the deputies.

Still, King’s rapid speech and a white paste on his mouth and tongue were noted. He was sweating heavily, his pulse raced, his hands shook and his eyes were bloodshot. He performed poorly in a series of sobriety tests. In his pocket, the report states, was a bottle filled with marijuana for which King had a medical license. Suspecting he was high, the deputies took him into custody.

Within hours, news of the arrest was everywhere.

Tests showed that his alcohol level was nearly at the legal limit and that he had traces of marijuana in his blood. After pleading guilty to a “wet reckless” driving charge, he was put under house arrest and ordered to enroll in a drunk-driving program.

By his own account, his drinking continues, as does his pot smoking — medical marijuana offering physical relief from the headaches and pain he says he has suffered since the beating.

He says he “will always be in recovery.” But then he adds, “I’m one of those guys who can stop when he needs to. I know my limits. Besides, a little bit here and there keeps the edge off. And after what I’ve been through....”

He describes his most recent nightmare, which was only a few weeks ago: He saw the faces of all four LAPD officers accused of striking him.

On the street, the sight of a police officer fills him with anxiety. This is why, he says, his pulse rate climbed during the Moreno Valley arrest.

“My God,” he says, “it ain’t ever going to go away.”

On a recent day, during lunch at a local restaurant, he carries in a flask and takes a sip. Apple cider and champagne, he confides.

Then he tells this story:

“It was like three months ago. I was on a Metrolink, coming home from L.A.” A young sheriff’s deputy walked in. “He was just doing his job....”

As King recounts the incident, his eyes narrow, his right hand shakes.

“My mind is flashing back to the incident in ‘91,” he says. “Because I see the uniform, so immediately I am thinking back to that beating.”

It was a struggle, he says, to not dwell on “bad thoughts.”

Bad thoughts?

“Kick some ass. Revenge. I mean, all kinds of things. Your mind will drift off so you gotta hold on for yourself. You find yourself in a bad way if you let your mind drift too long, you know.”

As King retells it, the deputy turned toward him and said, “I thought that was you, Rodney! How you doing, man? How is everything going? Good? All right, you take care of yourself.”

“Wow,” King says. “So you sit, and you think, ‘Oh, times have changed.’ ”

His words hang there. “Times. Have. Changed.”

Rodney King tilts back his flask and takes another sip.

He is grinning.

One in a series of stories about the 1992 riots and how they reshaped Southern California.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.