The most influential person on the coastal commission may be this lobbyist

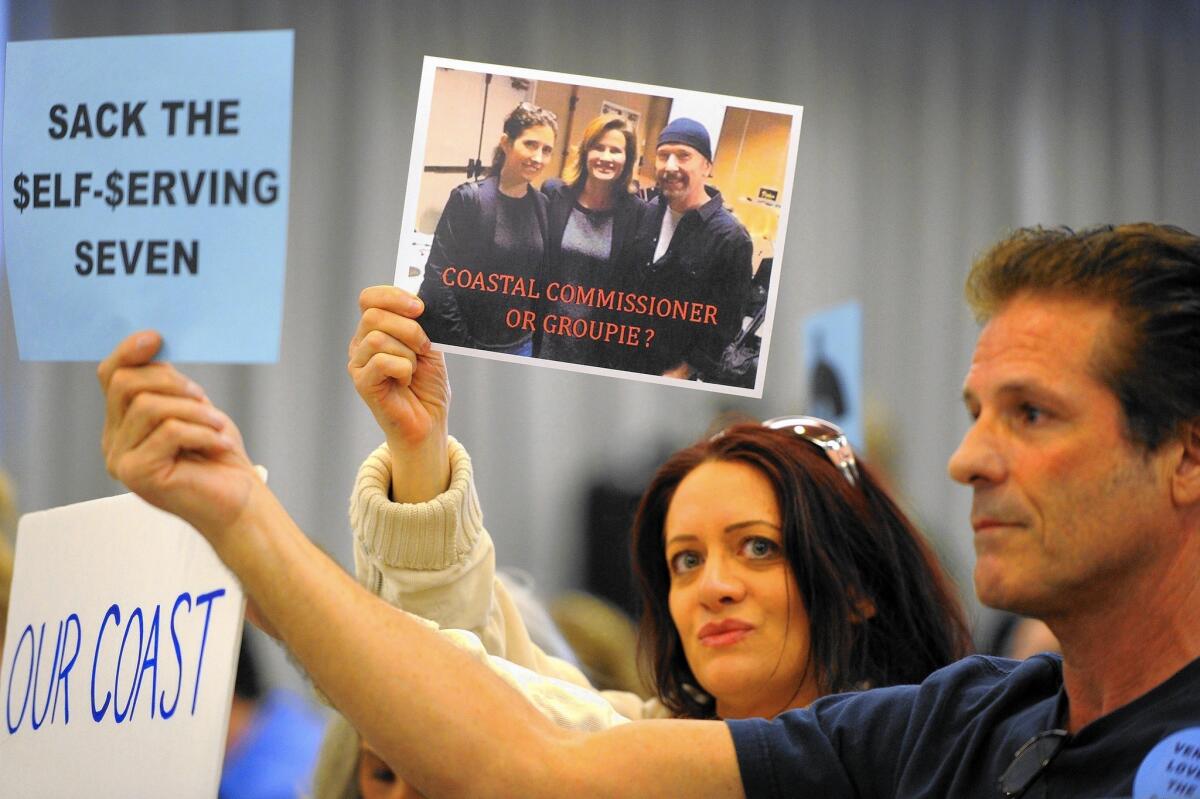

Ilana Marosi holds a photo of Commissioner Wendy Mitchell with U2 guitarist David Evans.

- Share via

The California Coastal Commission faced a scheduling nightmare when its monthly meeting landed in San Diego at the same time as Comic-Con.

With 130,000 costumed revelers headed to town in July 2012, hotels were booked, and the panel was in a jam. Then Commissioner Wendy Mitchell saved the day, managing to secure 23 rooms at the Marriott Marquis, a prime waterfront spot adjacent to the convention site.

------------

FOR THE RECORD:

Coastal commission: In the April 24 Section A, a photo caption with an article about a lobbyist’s influence with the California Coastal Commission misidentified Dan Carl as a commissioner. He is deputy director of the commission’s north central coast district. —

------------

Turns out she had some help: At Mitchell’s behest, the reservations actually were made by Susan McCabe, one of California’s most powerful lobbyists. At the time, McCabe represented the hotel in a $100-million expansion project pending before the commission.

That she was in a position to intercede in the lodging crunch raised some eyebrows on the commission and speaks to her close relationship and prominent standing with a state agency that regulates development along California’s 1,100-mile coast.

“She is smart, and she is charming,” said Mel Nutter, a Long Beach attorney and former coastal commission chairman. “She has been as close as she could be to a number of commissioners.”

Lobbyist, winer-and-diner, political insider and owner of McCabe & Co., a Marina del Rey consultancy, McCabe by all accounts dominates the field of coastal developers’ agents. Many also consider her unrivaled in behind-the-scenes discussions with coastal commissioners.

Unlike other regulatory agencies in California, the coastal commission may be lobbied directly. Although legislation is pending to change it, state law allows members to communicate or meet privately with interested parties, including project applicants and their agents, as long as they disclose those phone calls and meetings and what was discussed.

In the last 15 months alone, commissioners have reported more than 100 such ex-parte exchanges with McCabe, far more than with anyone else who represents business interests or environmental causes, commission records show. During their stay at the Marriott in 2012, at least two commissioners toured the project site with her, the records show.

McCabe, 62, said communication is an integral part of her work, noting that she represents more single-family homeowners than major developers.

“I love what I do,” she said. “I have a passion for our coast, and I like to help people get through what can be a difficult process for them.”

McCabe has been thrust into the spotlight by the Feb. 10 ouster of Charles Lester, the commission’s executive director. The panel voted 7-5 behind closed doors to fire Lester, over the objections of more than 200 people. His firing, with little explanation afterward, intensified the focus on what Nutter and other critics say is a lack of transparency on decisions that affect California’s most valuable real estate.

McCabe’s influence and her involvement in two projects, a rock star’s proposed ridgetop compound in Malibu and a small residential development in Pismo Beach, have made her a fulcrum in that debate.

Her supporters say that kind of attention comes with being a strong advocate for the developers, businesses, local governments and landowners she represents. Her critics counter that she wields too much influence — and too much of it beyond public view.

“I admire her talent, but it poisons the system,” said Ralph Faust, the commission’s general counsel from 1986 to 2006. “I will tell you straight out that ex-parte communications should be banned. They are really at the heart of what the problems are and what people are complaining about when they say that decisions are being made off the record.”

::

McCabe’s clout is built on business and political connections spanning four decades.

After earning a master’s degree in public administration from Cal State Sacramento in 1977, McCabe worked as an environmental advocate, an administrative assistant to Assemblyman Terry Goggin (D-San Bernardino), whom she later married and divorced, and as a consultant to the Assembly’s Energy and Natural Resources Committee.

In 1986, she was appointed to a two-year term on the coastal commission, and then served two years more as an alternate. Afterward, she spent about a decade as a legislative lobbyist and founded her own firm in 1999.

McCabe & Co. specializes in coastal commission cases but has represented a variety of clients on legislative issues, state lobbying reports show. They include a California Indian tribe, a New York hedge fund, a builder of liquid natural gas terminals, a tobacco company, an industrial-hemp trade association, a firm that runs private prisons and the now-defunct Citizens for Fire Safety, a group later shown by the Chicago Tribune to be a front for the makers of toxic flame-retardant chemicals.

In 2007-2008, McCabe & Company’s highest-paying legislative clients were Newmont Mining, $300,955; Lennar Homes of California, $220,028; and Citizens for Fire Safety $200,468, according to the state reports. In 2009-2010, Poseidon Resources, which builds desalination plants, topped the list at $262,013, the reports state.

McCabe still represents Poseidon’s interests, including a $1-billion project in Huntington Beach. The 200-plus other coastal clients listed on her website include cities, resorts, SeaWorld, Pepperdine University, the ports of Los Angeles and San Diego, and entertainment moguls Barry Diller and Jeffrey Katzenberg.

How much McCabe earns is anyone’s guess. Unlike legislative lobbyists, neither agents nor clients with projects before the coastal commission must report those numbers, and McCabe does not disclose her client fees. By all indications, however, business has been good.

In 2014, McCabe sold one home in Palm Springs and bought another for just over $2 million, according to online property records. The 4,000-square-foot house in the Old Las Palmas neighborhood features four bedrooms, four baths, hand-carved beams, multiple fireplaces, a wine cellar and a detached guest house.

Her primary residence is a 3,700-square-foot, four-bedroom home in Marina del Rey. It has an assessed value of about $1.6 million, public records show. Several acquaintances said she has called it “the house that Peter Douglas built for me,” a joking reference to the commission’s late former executive director.

McCabe said it was someone else who told that joke and that Douglas repeated it to her.

::

Over the years, McCabe has emerged as the top player among developers’ representatives, landing many projects valued in the tens of millions of dollars to $1 billion or more.

Sara Wan, an environmentalist and former coastal commissioner, said McCabe’s influence has tracked the growth of her business.

“It goes hand in hand: If you have influence you get projects — and vice versa,” Wan said.

Wan and others attribute McCabe’s prominence to several factors, including her knowledge of the Coastal Act, the 1976 law that governs development, beach access and marine resources along the coast, and her close attention to her clients’ wishes.

They also cite her political ties and her access to commissioners.

“She has done a particularly good job of creating and developing relationships,” said Wan, who served 15 years on the commission beginning in 1996 and is no fan of ex-parte communications.

McCabe is well known for her Sacramento connections, in the Legislature and in the executive branch. She has known Gov. Jerry Brown “for many, many years,” she said, but disputes a widely circulated story that she can walk into his office without an appointment.

“I can’t get a meeting with the governor with an appointment,” she said.

Of particular note has been McCabe’s friendship with Commissioner Mitchell, a political consultant who says she recuses herself when her clients have business before the commission.

McCabe said she has known Mitchell for years and recommended her for a vacancy on the commission late in Arnold Schwarzenegger’s administration. She said Mitchell was one of many friends she’s made in government and political circles.

“You can’t be involved in progressive Democratic politics, in my instance for 40 years, and not know a lot of people,” she said. “My expertise is in the natural resources area. I tend to know all of the people in that area.”

Mitchell declined to be interviewed.

McCabe’s supporters include consultant Adi Liberman, a commission alternate from 2006 to 2012, and Joe Edmiston, executive director of the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy, a state parklands agency.

“Whether it was a private party or a public agency she was representing, she was willing to tell her clients what was reasonable and what wasn’t, what the staff could do and couldn’t do,” Liberman said.

Edmiston lauded McCabe’s “great reservoir” of knowledge about the commission’s inner workings. She represented his group’s interests in lengthy fights with the city of Malibu over the conservancy’s use of Barbra Streisand’s former estate for private events and other functions.

“We were happy to have someone with her experience with the commission,” he said. “She was always straightforward, and I always found that she gave us good advice.”

Other of McCabe’s work wasn’t so well received.

In 2010, her efforts backfired when The Times published her emails about a major remake of the downtown San Diego waterfront. In an email to her client, the Port of San Diego, she boasted of furnishing talking points to one commissioner.

“It’s called spoon feeding — but we’re happy to do it! :-)” she wrote.

Embarrassed port officials apologized to the coastal commission and did not renew McCabe’s contract.

More recently, opponents of U2 guitarist David “The Edge” Evans’ five-mansion project above Malibu were dismayed to learn of a meeting McCabe helped arrange in Ireland last fall between the musician and Commissioner Mark Vargas. Weeks later, Vargas joined in the panel’s unanimous approval of the development.

McCabe’s influence also became an issue late last year when Pismo Beach homeowners who opposed a nearby residential project spotted her having dinner and drinks with Commissioner Erik Howell and the developer. Howell, a Pismo city councilman, voted for the project the next day, reversing his earlier opposition.

What the neighbors didn’t know at the time was that Antoinette DeVargas, McCabe’s operations manager and longtime domestic partner, had weeks earlier contributed $1,000 to Howell’s City Council campaign. Residents have since asked the state Fair Political Practices Commission to remove Howell from the commission.

Vargas and Howell have denied any undue influence.

::

McCabe, who employs two former coastal commission staffers, is known for keeping a low profile and a relentless watch on the panel’s proceedings. She attends nearly every meeting, but rarely steps to the microphone, deferring instead to her clients and associates to make presentations.

She compiles detailed briefing books for the panel and, according to regular attendees, her team delivers recommended revisions to commissioners who sometimes adopt them with little or no public review or discussion.

Susan Jordan, director of the California Coastal Protection Network, cited as an example the Ranch at Laguna Beach, a hotel renovation. Commission staff had sought a developer’s fee of $1 million or more to mitigate the loss of affordable rooms. But the panel dropped the fee with no further public discussion after receiving “watered-down conditions” submitted in writing by an attorney working with McCabe, Jordan said.

“The commission voted to eliminate the fee that should have gone toward providing low-cost accommodations for the public and only required a much smaller donation for a trail,” she said. “I was appalled by the failure to vigorously protect the public interest. The developer essentially got away scot-free.”

The developer, Mark Christy, chafed at that assertion, saying that most of the commissioners opposed any mitigation fee in the first place. That he voluntarily agreed to pay $250,000 for a trail for pedestrian and bicycle access to the beach is a testament to his own long-standing environmental advocacy, he said.

“The commissioners overwhelmingly supported our simple restoration of this property on its merits, as did virtually the entire town of Laguna,” he said. “To this day, I cannot understand why anyone would do anything but celebrate the restoration of this icon.”

McCabe also is known for her considerable social skills, honed over countless meals and cocktails and at the occasional charity event or political fundraiser.

In November, she and Commissioner Dayna Bochco were among a dozen hosts of a fundraiser for Assemblyman Anthony Rendon (D-Paramount), with invited guests, including Commissioner Robert Uranga. Rendon later reported contributions of $1,000 each from McCabe, her partner DeVargas and her client Poseidon Resources.

In March, Rendon was sworn in as Assembly speaker, a position that appoints four of the 12 coastal commissioners. Although some might view McCabe’s support for him as an attempt to bolster her influence on the panel, she said it was nothing of the sort.

“I’ve known him for years and consider him a friend,” she said. “I think he’ll be a marvelous speaker.”

Follow on Twitter @kchristensenLAT

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.