- Share via

An immaculate metal box built in 1931 to symbolize the future bounced around the East Coast for decades before recently landing in Palm Springs for all to see.

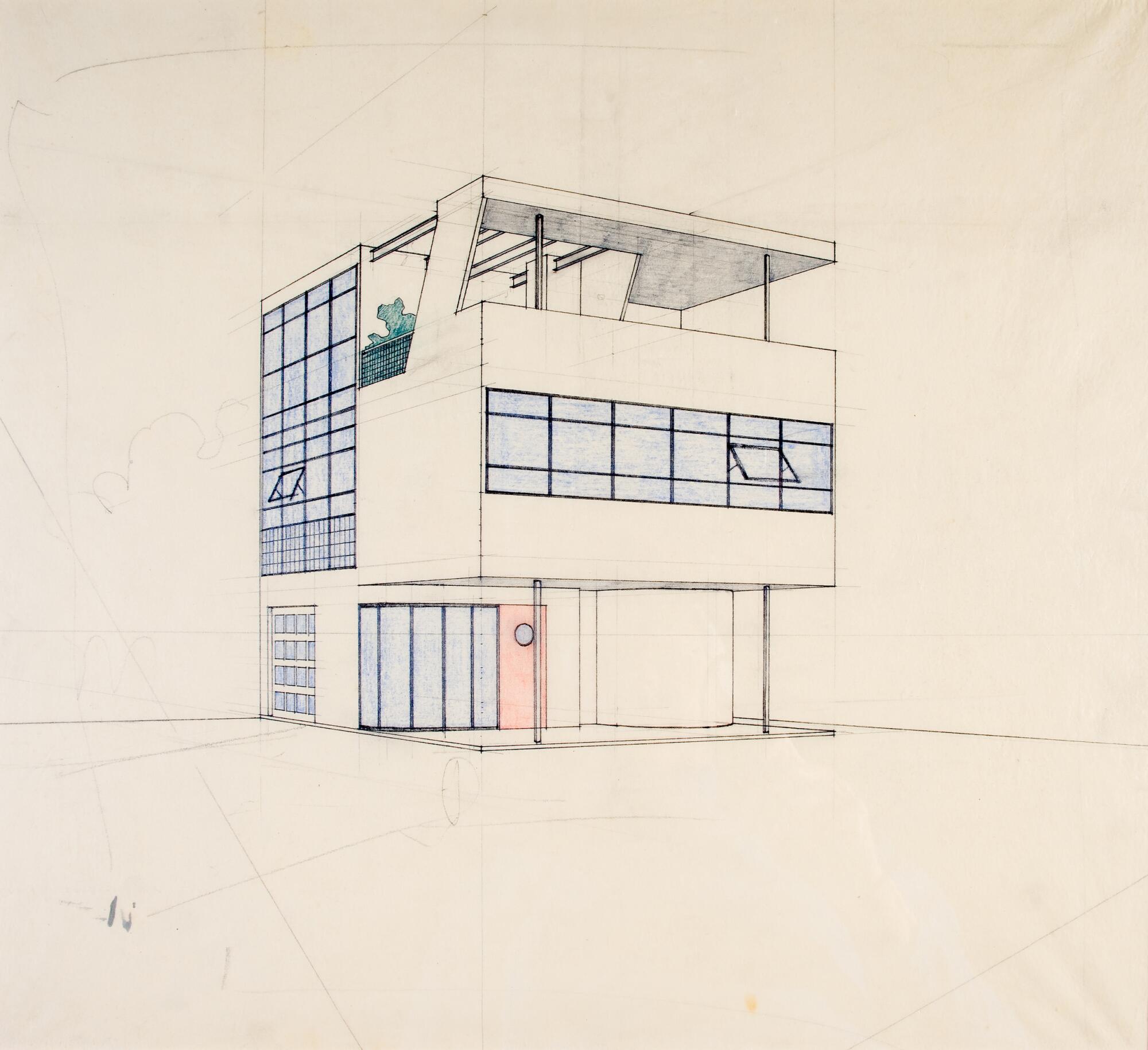

The first American home composed entirely of metal and glass was once an experimental housing prototype in New York. Now, the three-story, 1,100-square-foot Aluminaire House is the newest and oldest structure designed by Albert Frey in Palm Springs. The Swiss architect has been hailed as the father of Desert Modernism since he first took residence in Palm Springs in 1934.

“Here in Palm Springs, we often associate modern architecture with luxury, style and elegance,” Adam Lerner, executive director of the Palm Springs Art Museum, told an audience of 1,000 recently at the grand opening of the structure as a permanent exhibit. “But with the Aluminaire House, we are reminded that modernism is not just a style but an embodiment of ideas. Modernism is about making good design available to a wide audience.”

Rather than adapt the home to comply with current fire safety codes and the American Disability Act, the interior has been restored to its original condition but is inaccessible to the public.

“This is a little bit disappointing to us,” Lerner said, adding that the museum is raising funds to offer a virtual reality experience of the interior. The home sits on a gated site that is open during museum hours.

After the ribbon cutting, visitors packed through the gate to get a closer look at the Aluminaire House. Many tested the door handles and pressed their faces up against the glass along the ground floor in vain attempts at a peek inside, while others opted for the upward view into the stairwell — a gloriously abstract composition of steel beams against pastel-hued walls — visible through the double-height windows on its southern elevation.

The Shag House in Palm Springs is a joy-filled testament to midcentury optimism. It will be open to the public during Modernism Week, which runs Feb. 15-25.

“When Frey was in Paris working for [architect] Le Corbusier in the late 1920s,” says Joseph Rosa, a historian and author of Albert Frey’s eponymous 1990 monograph, “he was enamored by the methods of architectural prefabrication and standardization on display throughout Sweet’s Catalog,” an American building material and product periodical that had sent shock waves through European architecture firms for its highly rational approach toward mass-produced design.

In the hopes of combining European modern design ideals with American manufacturing capabilities, 27-year-old Frey set sail for New York in 1930 and found a creative partner in A. Lawrence Kocher, managing editor of Architectural Record magazine, who was then organizing the Allied Arts Exhibition — held the following year in the Grand Central Palace in Manhattan. “Kocher did the writing and publicizing while Frey did the design,” says Rosa of their collaboration on the Aluminaire House for the landmark event.

The metal doorknob of the Aluminaire House.

The Aluminaire House.

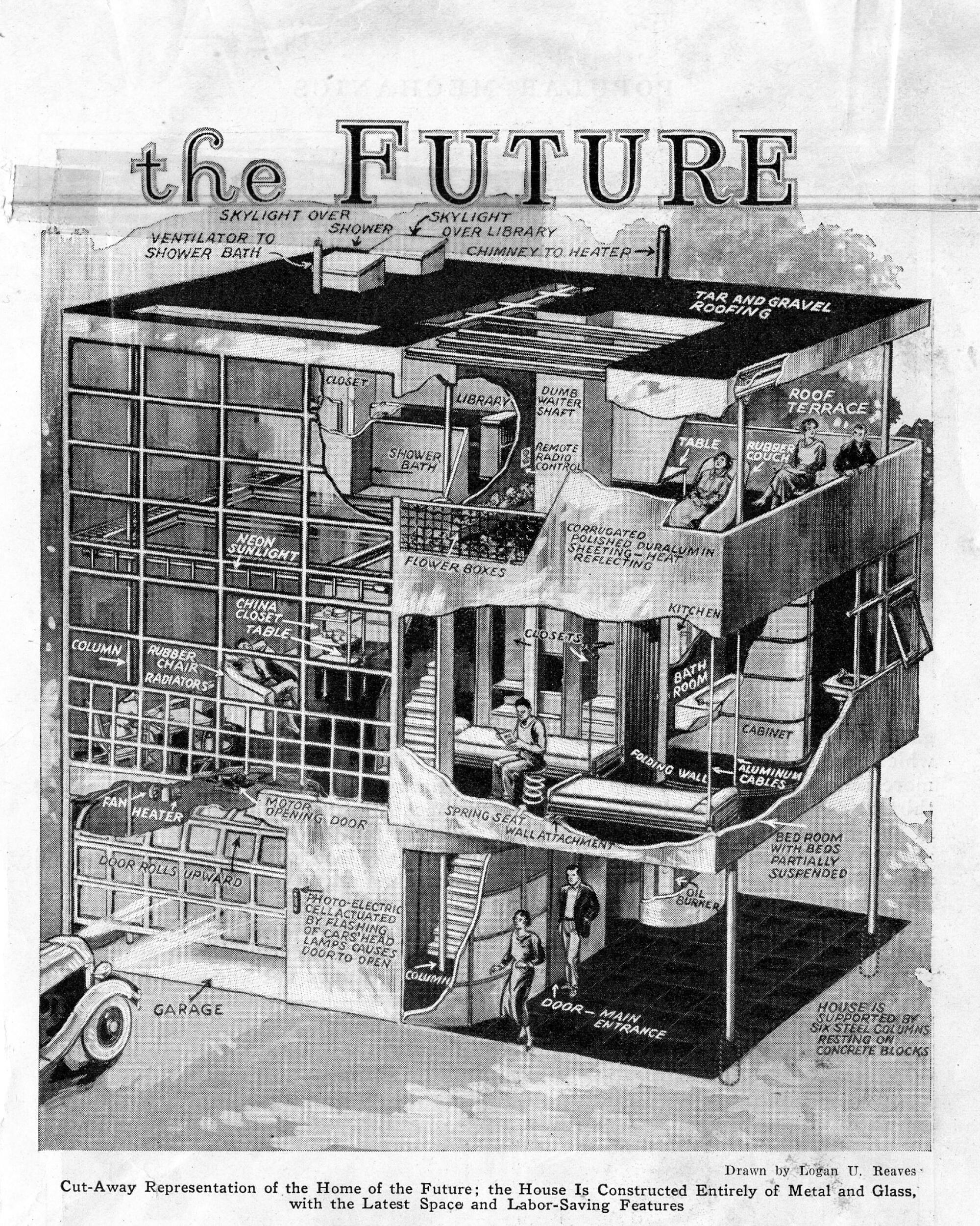

Frey wrote in 1988 that he and Kocher “had been discussing the need for low-cost housing in those Depression years. We thought that a small, single-family house, using the new methods of prefabrication and maintenance-free materials, would be both popular with visitors to the Exposition and offer a solution for the housing shortage of the times.” Aluminum was a lightweight yet durable cladding material, and its cost had dropped considerably following the end of World War I.

During the eight-day event, more than 100,000 visitors poked around the features of its multi-functional interior, which included built-in radios, overhead garage doors and a roll-away dining table. Surfaces were partly unfinished to reveal the steel frame and other novelties unique to the structure. Visitors peered into the interior from the second-floor balconies of the exhibition space circling the house.

Architect Wallace K. Harrison paid for the model to be disassembled, relocated to his Huntington estate on Long Island, and reconstructed as a second home for his family. Frey, meanwhile, took his passions to Palm Springs, where he designed several modernist structures across the region while cruising around town in a convertible sporting a license plate that read “ALUMI.”

The Aluminaire House now sits at Museum Drive and Tahquitz Canyon Way, at the bottom of the long, winding road to Frey House II, the spartan home Frey built for himself in the foothills in 1964 and bequeathed to the Palm Springs Art Museum upon his death in 1998.

The Aluminaire House at the Palm Springs Art Museum.

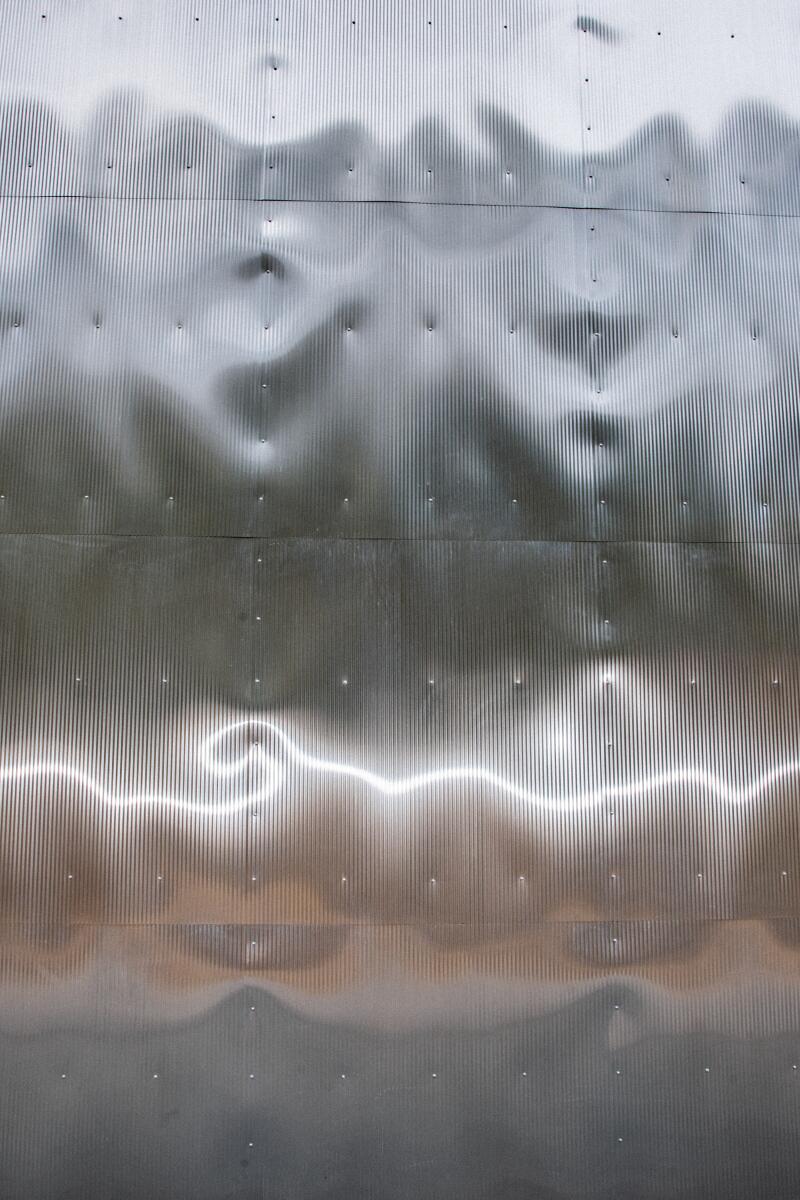

Details of the corrugated metal siding of the Aluminaire House.

Following Harrison’s death in 1981, the Aluminaire House was on the path to demolition before gaining the attention of New York Times architecture critic Paul Goldberger, whose 1987 article championed the timelessness of its principles, if not its aesthetics. “There is nothing, at first glance, particularly appealing about the Aluminaire House,” Goldberger wrote. But here, “the dream that modernism would show a new way of life to the masses actually had a flicker of reality to it.”

The New York Institute of Technology was soon called on to relocate the home to its campus in Islip, Long Island. “We decided to make it part of the teaching curriculum,” said Michael Schwarting, a former professor at the institute who, with a state preservation grant of $131,000, brought architecture students to the site to disassemble the house before cataloging the elements and transporting them within a storage container. “A screwdriver and a wrench is pretty much all you need to take it apart,” said Frances Campani, a former institute professor who, with her husband, Schwarting, established the Aluminaire House Foundation. For many years, Schwarting’s design studios approached the Aluminaire House as a hands-on, full-scale case study for historic preservation.

There’s more to Palm Springs than swimming and sunbathing. From Midcentury Modern furniture to vintage caftans and handcrafted pottery, there is something unique to be found in the shops along Palm Canyon Drive.

In 2004, the home was taken apart once again following the dissolution of the Islip campus. As they struggled to attract New York-based institutions to erect their kit of parts, Campani and Schwarting were invited by organizers of Modernism Week, an annual celebration of the Mid-Century Modern architecture across Palm Springs, to not only lecture on the Aluminaire House but also to consider the city as its permanent home. A truck filled with building parts headed west in 2017, and a capital campaign seeking $2.6 million inspired local philanthropists to chip in.

“The entire structure we received is original to 1931, along with the doors, windows and stairs,” says Leo Marmol, a museum board member and managing partner of the Los Angeles architecture firm Marmol Radziner, who coordinated the design team on site. Among the more challenging tasks were refabricating parts of the interior and the exterior aluminum siding and choosing its location near the main museum building. The design team decided on a former parking lot on the southern edge, where its front elevation now glows every morning at sunrise.

Two blocks south, the exhibition “Albert Frey: Inventive Modernist,” on display at the museum’s Architecture and Design Center until June 3, lovingly depicts Frey as the creative lifeblood of 20th century Palm Springs while gesturing to the first energetic sketches of the Aluminaire House.

“I can’t think of any other town that has such a complete timeline of an architect’s work from the very first house he did in America to his very last,” said Brad Dunning, the curator, during a public tour of the exhibition.

As an image, the Aluminaire House is, and will remain, as pristine as it did the day it was unveiled in 1931. But as a meaningful attempt to build dignified affordable housing — an amenity severely lacking in Riverside County — it’s unclear whether Palm Springs will feel the full weight of its new aluminum box. The Aluminaire House was more than an impenetrable monument to a style, and Frey knew that its purpose would be tough for the masses to internalize but could be accepted with instruction. “Appropriate education and explanation of form evolution will speed up the process of assimilation,” Frey wrote in his 1939 treatise, “In Search of a Living Architecture,” “and make possible the simultaneous creation of modern means and respective forms.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.