- Share via

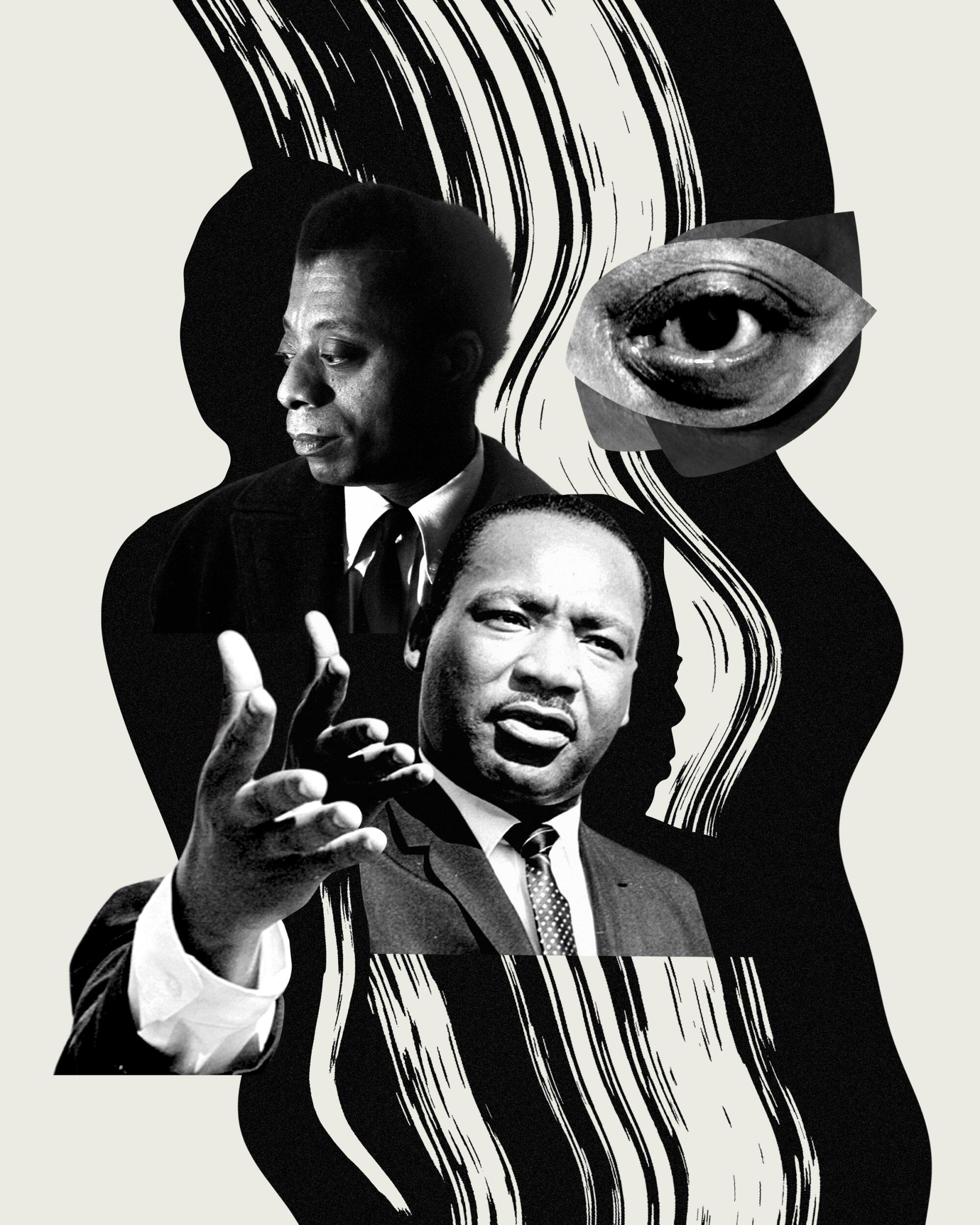

On March 16, 1968, Martin Luther King spoke at a benefit for Vietnam, held in Beverly Hills. James Baldwin and Marlon Brando introduced him. Brando’s introduction is not recorded. Baldwin spoke after Brando, extemporaneously and in parables about Black Sambo and Detroit’s relationship to Saigon and integration in the South. He seemed full of dislocated vitriol and his words landed tonally somewhere between rambling and total restraint. There were none of his signature epiphanies. Instead, Jimmy offered a matter-of-fact recapitulation of the civil rights struggle from 1954 to 1968 and named their current moment in 1968 “a culmination of that cavalcade of events,” from the Bus Boycott to desegregation of schools. He pointed out that Martin had spent those years in and out of jail, and that in many ways he was captive still, or stilted by his ability to remain decent in the face of oppression. What Baldwin didn’t explain was how that decency and resilience had by then become its own violence, a righteous self-sabotage both necessary and agonizing in King’s estimation. Baldwin closed with a clichéd but very literal innuendo concerning the stakes of it all: “It’s a matter of life or death.”

The audience clapped uneasily. This was an era during which clichés did not double as exaggerations; the introduction was a warning and a goodbye. King took the microphone, the final runner in a doomed relay — “There comes a time when silence is betrayal.” He assumed a tone of detached but prophetic ennui for the next 40 minutes.

In the 1950s, he quickly developed a reputation for being a gun-toting, switchblade-carrying man on one hand and an impossibly tender soul who could write love songs with the facility of angels on the other.

On that Saturday in 1968 — a date that coincided with the My Lai Massacre wherein members of the U.S. Army killed 500 Vietnamese villagers and proceeded to cover it up for years before reporting on it — King was in a purgatory between drama and dream, between Los Angeles and Memphis, between serenity and brutality. Like the films rushing toward their death scenes and catastrophes, he was that kind of star then, the leading man who leads by placing himself in danger so others can indulge the mundane carefree. But on the occasion of this speech, he seemed to forget where he was, breaking with the agendas of set and setting, refusing to be flattered by celebrity accompanists, no glints of admiration or joy in his cadence. He delivered oratory so technical, detached and devoid of demagogy and optimism, that maybe he was using Los Angeles for what it was, exploiting its optics to at last say the things he knew would bait his enemies into revealing their desperately malicious intentions.

That day in Beverly Hills, King made the link between poverty in the United States and the war in Vietnam, synthesizing both circumstances into one call for spiritual reckoning and reconciliation, and making him a clear and viciously targeted enemy of the state. The almost outrageous risk he was taking in moving from the expected exhortations for boycotts and passive resistance to a deeper and more cohesive systemic critique was undercut by a vocal style markedly more doctrinaire than his preaching and performative speeches. King was not in Los Angeles to deliver more flowers to the grave of that brotherly love which he had openly mourned and prayed over for decades in his calls for solidarity and unconditional peace; he seemed intent on exposing the necrotic contents of that crypt without remorse.

King and Baldwin must have been keenly aware of how their impromptu ensemble destabilized their reputations. They had roles, and they were in L.A. ruining them. 1968 was a year of breaking out of trances and they were not immune to breakthrough as they had not been immune to the entrancing momentum of “the movement,” which, by now, they both realized was headed toward a dead end unless they began to name the new tangible evils and dispel them.

King went on to emphasize the distinction between subsidized white farmers and former slaves, between the thieves in industry and thieves of culture. He belabored the point, suggesting unambiguously that it was time to redistribute land and wealth. And then, in a disgruntled caveat, he described a recital at the integrated school in Atlanta that his kids attended at the time, where they were made to sing Dixieland, which the school’s curriculum called “the music that made America great.” He was indignant at his own complicity, as if maybe he was rethinking his stance on integration and learning its proximity to indoctrination firsthand. At once weary and renewed, his voice dragged like he was stuck in a nightmare in slow motion. Subconsciously, this was part of his antagonistic surrender to the forces he knew would attack him for simply organizing his thoughts the way he had. He was killed 19 days later, on April 4 of the same year.

You cannot beg a god for forgiveness, but you can be ready when he hints at offering it after a long standoff.

King’s ceremoniously unceremonious Los Angeles interlude came during the ill-fated stretch of days and events leading up to his murder. It’s the only time I’ve ever wondered if succumbing to Hollywood affiliations and using them for amnesty could have saved or shielded a man. Would MLK have been safer pantomiming himself around celebrities and writing movies about the movement than he was leading it? Does that alternate dimension or absurd asylum matter? Would he have wanted to be saved and sanctified under celluloid and inducted into the fame of fictions instead of the spectacle of martyrs? Or was tragedy the best refuge from either outcome? Why was his obsession with peace both dismissed and criminalized until it left him bloody and sacrificial? Would he have been spared any of that violence as an actor in films about his potential selves and paths? Has cinematic activism ever helped us litigate what we call freedom, or is it just nice to watch people committing harrowing deeds on the big screen before returning to the comfort of our own complacency? How did the audible turmoil in King’s tone that day in Los Angeles turn into his fearless and fervent pronouncement the night before he was murdered in Memphis: “We’ve got some difficult days ahead, but it really doesn’t matter with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop, I don’t mind?”

Today, the lines between the archive and the Hollywood movie are blurred in collective human memory, which is really an art of collaborative forgetting, and then turning that selective amnesia into nostalgia we can commodify. Nostalgia works because it is inherently blurry and malleable. We cede the agency of remembering to the nostalgia machines. We expect that they have neatly stored and codified all of these documents so that we don’t have to; we can simply glamorize that code and conflate it with cinematic gesturing. Especially for that decade between the 1950s and ’60s within which James Baldwin and King speak — we have conjured all sorts of myths about the dynamics between iconic men and women, most of them apocryphal and uninteresting.

That gaudy mythic terrain helps us objectify the era and do to artists and activists from that time what we do to one another now: imposing disembodiment so we can refashion them around our own psychic deficiencies. This ensures that no movement will ever succeed again. Our reflexes and muscle memory will force us to turn radical solidarity into performance and projection, and empty prestige before we see it through. We are too good at aestheticizing struggle and terror, like a scene in a movie. King, we tell ourselves, was harmless, benevolent, steadfast. His beauty was uncomplicated by vice or even exasperation, is the lore we are sold. His voice never goes cold, never veers into the crucible. When it does — and we have evidence, a whole radio of examples — we pretend the document is the hallucination and grasp the myth a little tighter until we have extracted King from himself.

L.A.’s rich cultural history is alive through the life and work of the city’s unofficial poet laureate. Just ask her brother George Evans.

We subject James Baldwin to the same false scrutiny. We find him beautiful in a way that erases his subjectivity and heralds the pseudo-intellectualism of this era. Not because we read his words but because we’ve heard of them — the soundbites are delicious and make us feel like we know the rest. Then they mass-produce tacky merchandise in this extractive spirit with awful slogans like “We are our ancestors’ wildest dreams.” Meanwhile we are tormenting these ancestors with a new round of fake folklore every few years so we don’t have to face how real they were and still are. We don’t know them at all. We’ve never listened to them closely on a dejected Saturday and allowed them to falter and flail into heroic oblivion. We are dismissive when they name a crisis for what it is, and we mistake their prophecy for serendipity. Their Hollywood ending is either mutilation or selective muting. Because their pacifism was more un-American than their Blackness, King and Baldwin left their shared podium in Los Angeles like fugitives and under heavier, more meaningless surveillance.

James Baldwin as a presence possessed all the gravitas of a movie star, and all the rigor of an angry god. His rancor was smooth and charming, but he was not prone to gratuitous flattery. He was better at shade than fawning, he lived ahead of time, in the world of “Paris Is Burning” wherein “shade is a form of reading.” I am prone to fawning over him because the subtle arrow of his intellect wounds and stuns me simultaneously. And because he, who told us the purpose of the soul is to bear witness, was himself rarely seen through and through. He was made into a prop, and still is, for an idea of intellectualism and soul so well coordinated they become unreal to those who possess less of both. Jimmy Baldwin was simply too immaculate to benefit from the light emanating from him as much as others did and still do.

Privately, he was almost self-effacing, but the razor of his gaze became hagiography when he examined his friends. “They’re killing all my friends,” he once quipped, when asked if it was difficult to focus on his writing in the late 1960s. It was difficult just to live. As preemptive revenge for the assassination spree he would have to witness, and the lonely fallout, he wrote like a floating dazzle or the resurrected spirit of the slain come back swinging and chanting as if no terror had occurred, as if the script must go on and build itself of the ruins. He refused to kill off his heroes with betrayal — he kept talking and writing about the friends they had killed, at his peril. His showmanship was astonishing, and I think it almost broke him. In Hollywood they tell you writers write for pleasure or attention. In real life, and in the life of Jimmy Baldwin, he sometimes had to write to deflect attention from his own being, because a star quality for a writer is a partial curse. He was both the reluctant romantic lead of his own story and the one who would have to write his role so that it could exist, and then perhaps write himself out of it to make room for his dead friends.

Baldwin is the one who was left behind, left in Los Angeles, Harlem, the South of France, the blunted machine’s hungry ghost of a memory, still speaking, while his friends were killed or went mad. He didn’t even get the luxury of real madness except through his characters and the ghosts of his friends, and even then, most of his characters are so self-aware they feel real and human. His friends are immortal.

The 1960s closed like a trapdoor and became the altar of the inadequate future wherein dreams and nightmares come true, together, like a sad inevitable ballad by a great jazz ensemble. James Baldwin and Martin Luther King are that ensemble, stuck in Los Angeles, 1968. This day they spent, exhausted together on the crossroads of here and gone, chaperoned by Marlon Brando and the shadow of death, is the kind of convergence they make movies about, so we forget it really happened.