- Share via

This story is part of “Discourse,” a fresh look at the dire state of the bicoastal conversation — free from corniness and cliches. Check out the whole issue — the “New York” issue, if you’re reading between the lines — here.

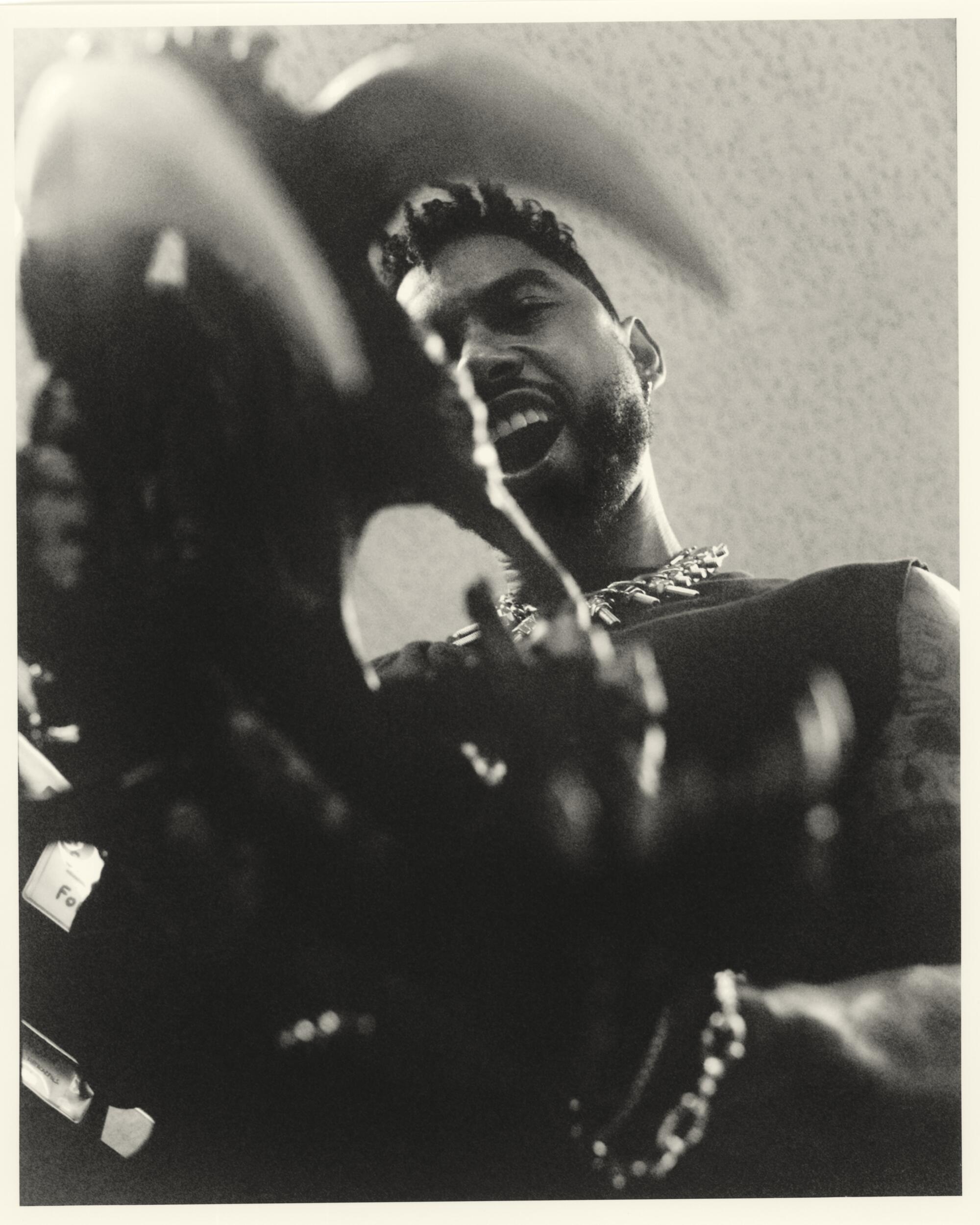

In bouldering, a “problem” is another name for a course the climber can take. Different problems require specific combinations of mental and physical agility. Miguel, the songbird from San Pedro whose voice has transcended genres and generations, is transfixed with one problem in particular: A3. With his hands on his hips and head cocked, wearing a black cutoff tank and stretchy black shorts, he’s been assessing this wall at the Hollywood Boulders climbing gym for at least an hour, tracing the constellation of green handholds and footholds, imagining different possibilities, charting alternative courses. He’s attempted it multiple times and still it’s evaded him. Every few minutes, he tries again. Surveying the scene — a cavernous space with vaulted ceilings that’s giving club more than gym, full of hot, sporty types with chalky hands — Miguel says he can just come back. But you get the sense he won’t be moving on until he makes it.

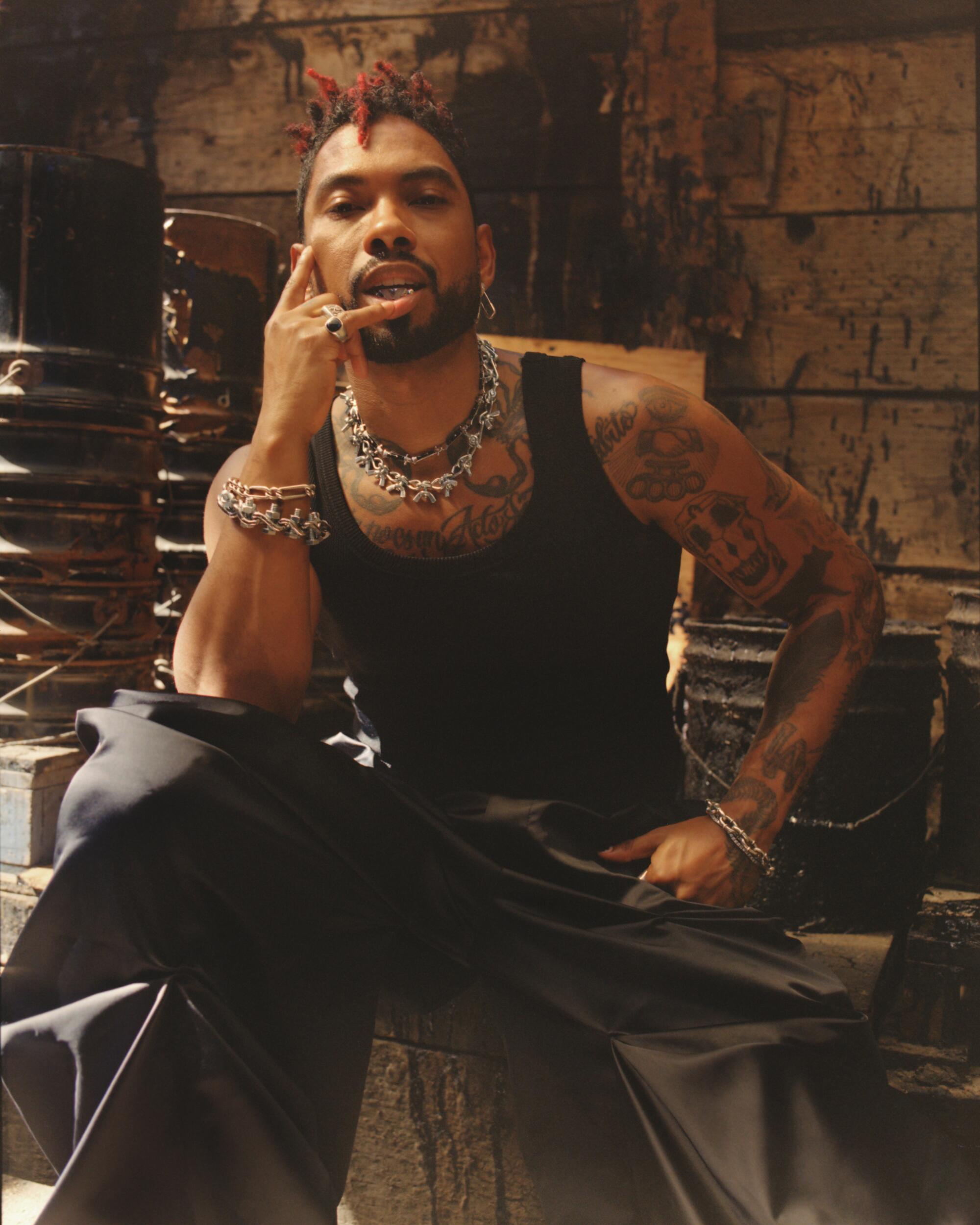

Miguel has made a practice of pushing his body to the physical limits in the last year through a lot of “fully immersive, visceral experiences” that “may speak to some sort of wanting to not feel numb,” he says. It was not long ago that he went rock climbing for the first time in preparation to scale 30 floors up a building for a Sony campaign. In June, he posted a picture of his back on Instagram, brick red blood stains running down his white tank top. It came after a session doing body suspension, the ancient body modification practice where large metal hooks are placed in the back from which the participant is hung. It’s meant to be a spiritual test, or meditative ritual, and for Miguel, an exercise in trust. “Initially it was a bit of, ‘What is the most extreme way to push outside of what’s expected?’” Miguel says. “How far can I go in demonstrating how far I’m willing to go for art, for conversation? I couldn’t have known how committed I was to the real purpose of this s— until I had hooks in my back.” He remembers feeling the weight of his body draped over the metal as heavy as the fear and control he was being urged to let go of. “It was a scary and freeing experience and emotion to go through because it’s such a light switch,” he says. “It has so much to do with pain. What does pain mean?”

When he posted the bloody photo on IG, comments from fans flooded in: “Ugh they cut your wings angel?” “[T]ell her stop scratching.” The idea that Miguel, R&B’s golden boy throughout the 2010s, is using physical pain as a vehicle for spiritual transcendence may hold some discord for fans who see him — and his music — as a time capsule. But Miguel has been publicly evolving in real time, chasing the ecstatic and exploring the limitations of commitment for years — from “Sure Thing,” a song he wrote when he was 17 that this year became a viral success and radio hit through TikTok, to the leap heard around the internet at the Billboard Music Awards, to his recent divorce from Nazanin Mandi.

The L.A. artist taps into the ways in which God shows up, and how to honor that in real time.

Still, public moments and perceptions have a way of cloaking celebrities in a kind of mythology that’s hard to shake. The narratives and ideas Miguel’s fans have placed on him — sex god, romantic, angel, millennial women’s collective husband — are plenty. But Miguel is just not in a place where he has the luxury to care anymore. His new album, out this fall, charts the “manic nature of growth,” Miguel says. Mac Robinson, a longtime friend and producer on the project, calls it a “full revision of everything that he’s learned, everything he’s been through.” The album, his first in six years, is sonic proof that he is plotting his way through problems: an exploration of the condition of pain and its relationship to progress. At 37, Miguel finally feels free to explore personal and spiritual depths. “Anyone who’s here for the one-dimensional version of me is not really here for me.”

Miguel grew up in apartment 24 on Third and Centre in San Pedro, somewhere he calls “the most obscure place in L.A.” He was raised a Jehovah’s Witness, and remembers him and his brother, Nick, who he calls his best friend, being intensely sheltered by his mother. Most experiences were filtered through the lens of a religion, which set the foundation for what he describes as a delayed interaction with the world. (He considers himself nondenominational now, but the spirit of something greater has never fully escaped him. “Music is spiritual,” Miguel says.)

And his gifts were encouraged. His mother, a Black woman from Inglewood who worked as a clerk for an architecture firm, loved soul music. His Mexican American father came to the U.S. when he was 3 years old from Zamora, Michoacán. He loved everything from classic rock to hip-hop and regularly brought home instruments from the swap meet to tinker with. Miguel’s parents split up when he was 8 years old, which is around the time his dad was going to Cal State Dominguez Hills to become a teacher. One might joke that his dad was in his breakup era — that specific time when you’re freshly single, and the outward momentum, or space to become a different version of yourself, works like a magnet. “You want to learn something?” Miguel asks, rhetorically. “Break up with your significant other.”

Miguel met his ex-wife, Nazanin Mandi, when she was 18 and he was 19, during a behind-the-scenes interview she was conducting on the set of his first music video. (Mandi asked him if he had a girlfriend, to which Miguel replied: “No, but I’m looking for one.”)

For years, at the height of the era when people used the #couplegoals hashtag sincerely, Miguel and Mandi were it. They were both beautiful (Mandi is a successful model, as well as a transformational life coach and author). They had fallen in love before Miguel blew up, which back then somehow seemed important. And despite their public ups and downs, they gave off the impression of being solid and genuinely in love, a rarity in the industry.

Freak City’s latest collection is a body of references that calls back to the ideas that shaped the cult brand into what it is: a celebration of irreverence, outcasts, underground culture, music, graffiti and the city that it calls home.

A 2018 wedding at Hummingbird Nest Ranch where they danced in each other’s arms to Miguel’s “Banana Clip” felt like a fairy tale ending for a relationship that had weathered the on-and-off periods, some long enough for the then-couple to date other people. “There was a connection there that I knew was real and that’s what kept us together,” Miguel said on Mandi’s podcast “Ladies Like Us” in 2019. Even after they initially announced their split in September of 2021, they briefly reconciled, celebrating a short-lived reunion on Instagram: “…heal the root so the tree is stable,” Mandi captioned her post. “I’m so proud of us. The Pimentel’s xoxo.”

There has always been a sense in Miguel’s music of wanting to hold on, of a kind of blind faith in making a situation work. His biggest hit, “Sure Thing,” is about the power of intuition — in what something has the potential to be if you just stay the course. But in October 2022, Mandi filed for divorce, citing irreconcilable differences. “You build something with someone,” he says, “you start adding rooms, levels, you got new floors and you want to remodel here and there. Ultimately, some changes, they may be too much for the foundation. You have to address that.” (Mandi did not respond to a request for comment.)

His new album — of which he won’t share the name or exact release date yet — was written partially parallel to his divorce, and some of the tracks offer an emotionally raw look into the stages of grief. “Always Time” is a song about bargaining — being tricked into thinking that when you love someone enough you have infinite moments with them to keep trying to make it work. It’s about holding on tight to your own detriment. “I thought there was always time / When you love this hard / When you try this hard / But it’s still not enough / Maybe this time love means letting go.”

With a new EP and outlook on life, the L.A. artist is reaching toward his truest self.

The most popular of Miguel’s songs often play out as a conversation he’s having with someone or something outside of himself — a future with a woman he loves, or could love, in songs like “Coffee”; L.A. itself in others like “City of Angels.” But noticeably, much of the new music feels like an exploration of Miguel’s relationship to Miguel. “It’s so much bigger than my relationship with my partner at the time,” he says. In the most felt songs on the record it sounds like he is singing to himself, or his therapist. On “Rope,” which Miguel wrote during a period of loss and turmoil, before he was married, he croons as if he’s in physical pain: “I’m hanging on to nothing / I’m hanging from the ceiling / Rope around my neck.” Recording it “was a weird depressive experience,” Miguel says. “I don’t think I’d ever been in a place where I was creating from there. … You build a reputation and a repertoire around love and sex and sexiness — these completely unrelated tones. Getting to the point where I allowed myself to express these emotions was a bit of a journey.”

The new album, in a lot of ways, taps into the lesser-acknowledged, darker spaces of R&B, a decisively Black genre that hasn’t always gotten its due. Historically, R&B has many nuances and deep connections across the musical diaspora. But it’s also been, from time to time, the object of regressive or conservative interpretations. Miguel has felt confined by the genre in the past, but the new music shows the expansions and mutations R&B has undergone throughout his career — a period that has coincided with a dramatic shift in R&B’s relationship to popular music. When he arrived, so-called “real” R&B was a slippery definition to pin down, and things were changing rapidly. The first No. 1 song on Billboard’s Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs of 2010 was “I Invented Sex” by Trey Songz featuring Drake. It was the autumn of Usher and Alicia Keys. Many of the sonic trends — the increasing hip-hop influence, EDM’s move toward the center of pop, the budding acoustic novelty of singer-songwriters — were tugging R&B in different directions. Beyoncé’s high-octane “Run the World (Girls)” and Rihanna’s “We Found Love,” produced by Calvin Harris, were inescapable.

Miguel has felt the ways in which his sound has been marginalized or not given space to expand in the popular imagination. “I’m not even going to mince words. I’m gonna keep it a buck,” he says. “I came up in a time where the industry was very different. And the promo department at the label was very antiquated. What I was doing and the artist that I knew that I was, there was no real space for that at the time.”

How the 21-year-old artist figured out the secret to life.

His voice has always been as undeniable and original as it is nimble — you know it’s Miguel when you hear him. Whether on “Remember Me” from Disney’s “Coco,” the various bangers from Miguel’s four “Art Dealer Chic” EPs, or “Leaves” from “Wildheart”: “As a singer, he’s incredible. Regardless of a lot of different musical iterations, that’s always been steadfast,” says D’Leau, a friend of nearly 20 years and producer on the new project, who met Miguel at the now defunct Temple Bar in Santa Monica. “That’s the purest part of him. Whether he’s on some R&B s— today, next time rock s—, almost some industrial s—.”

D’Leau, who served as Miguel’s music director for four years and worked on “Number 9” from the album featuring Lil Yachty, says there’s something different about the mental space Miguel is inhabiting: He has relinquished the need for delusional control. He has learned to trust. Miguel wrote 90% of the album, and self-produced 75%, as he does with all of his music, but there was a noticeable willingness to see where the music could go if he just allowed the collaborative process to do its thing. Most of it was about not shrinking away from what showed up emotionally, but rubbing up against it and seeing what it sounded like. Miguel describes it as “a wrestling with the conscious brain and getting it out of the way. … The real process — and the real work — is there.”

Sometimes that means leaving the door open for the eroticism that he has explored in the past in songs like “P— Is Mine” from “Kaleidoscope Dream” or “FLESH” from “Wildheart.” He doesn’t deny the energy if it comes knocking. In “Give It To Me,” a single that dropped in April, he sings of “giving you violent peace”: “You been locked down / I got the key, yeah / Lil’ devil, set you free.” In “The Killing,” off the new album, he sings in Spanish and English about obsession, the object of his affection being “wrist-bound, face down, ass up.” Asked if there are any specific things he needs around to do his work, he jokes: “I need a couple switchblades. I need some women in some thongs.”

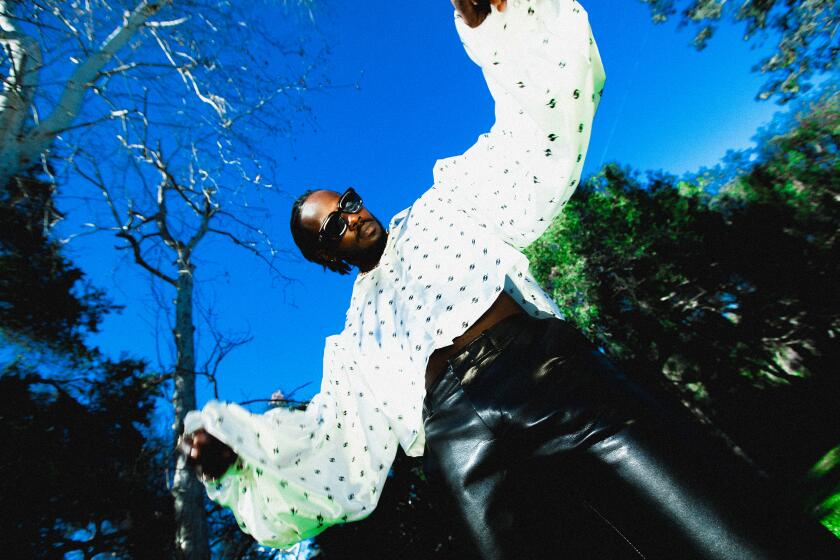

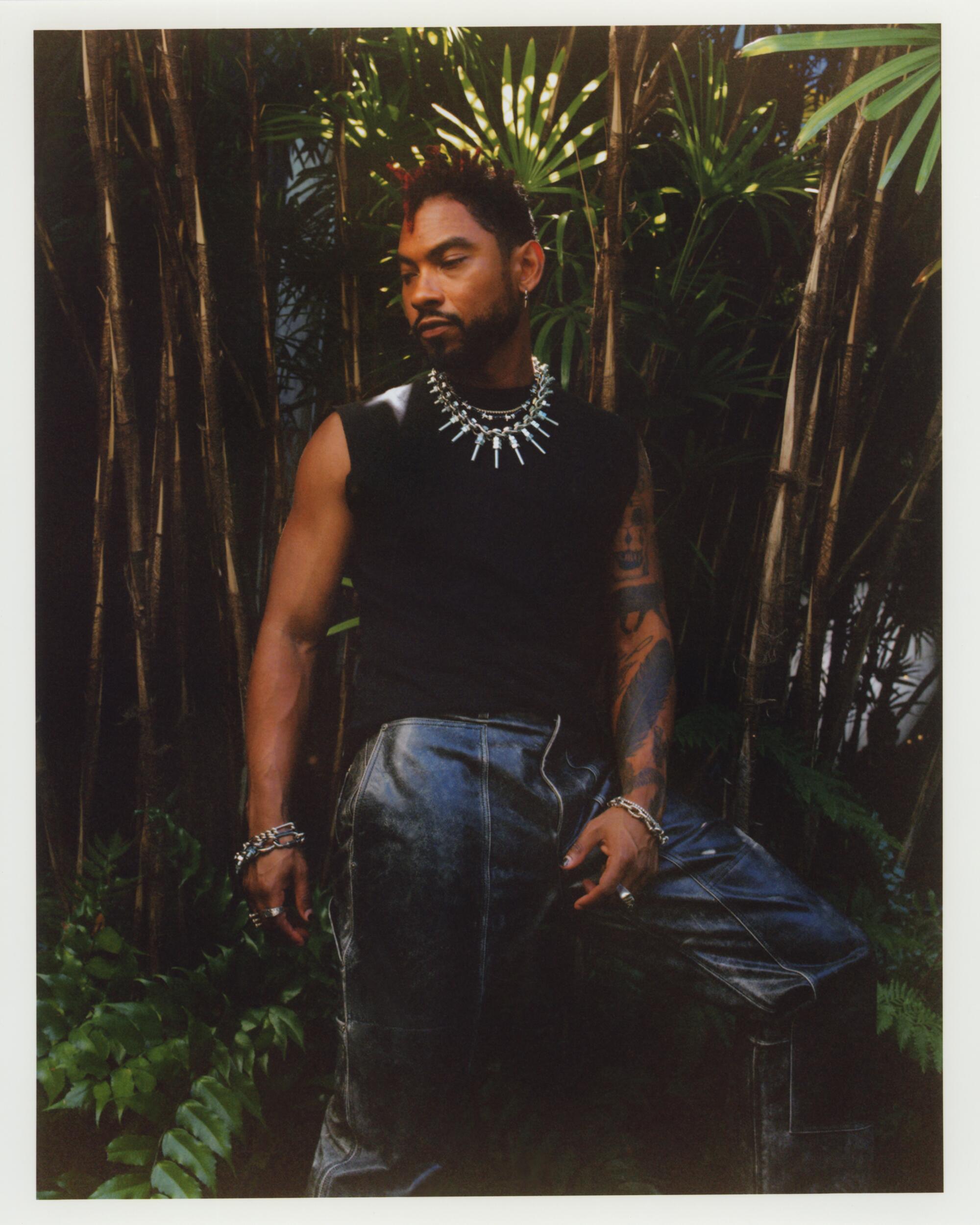

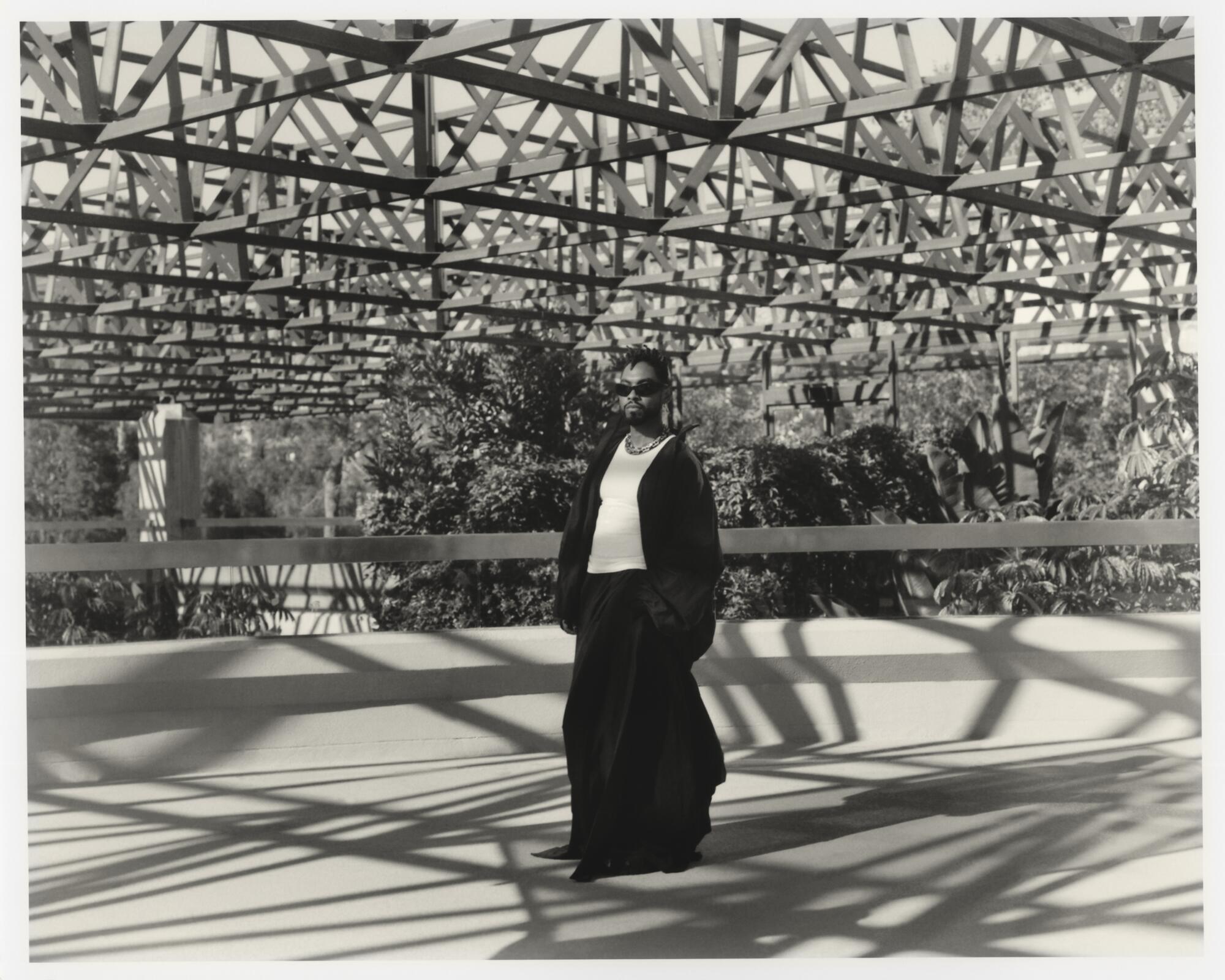

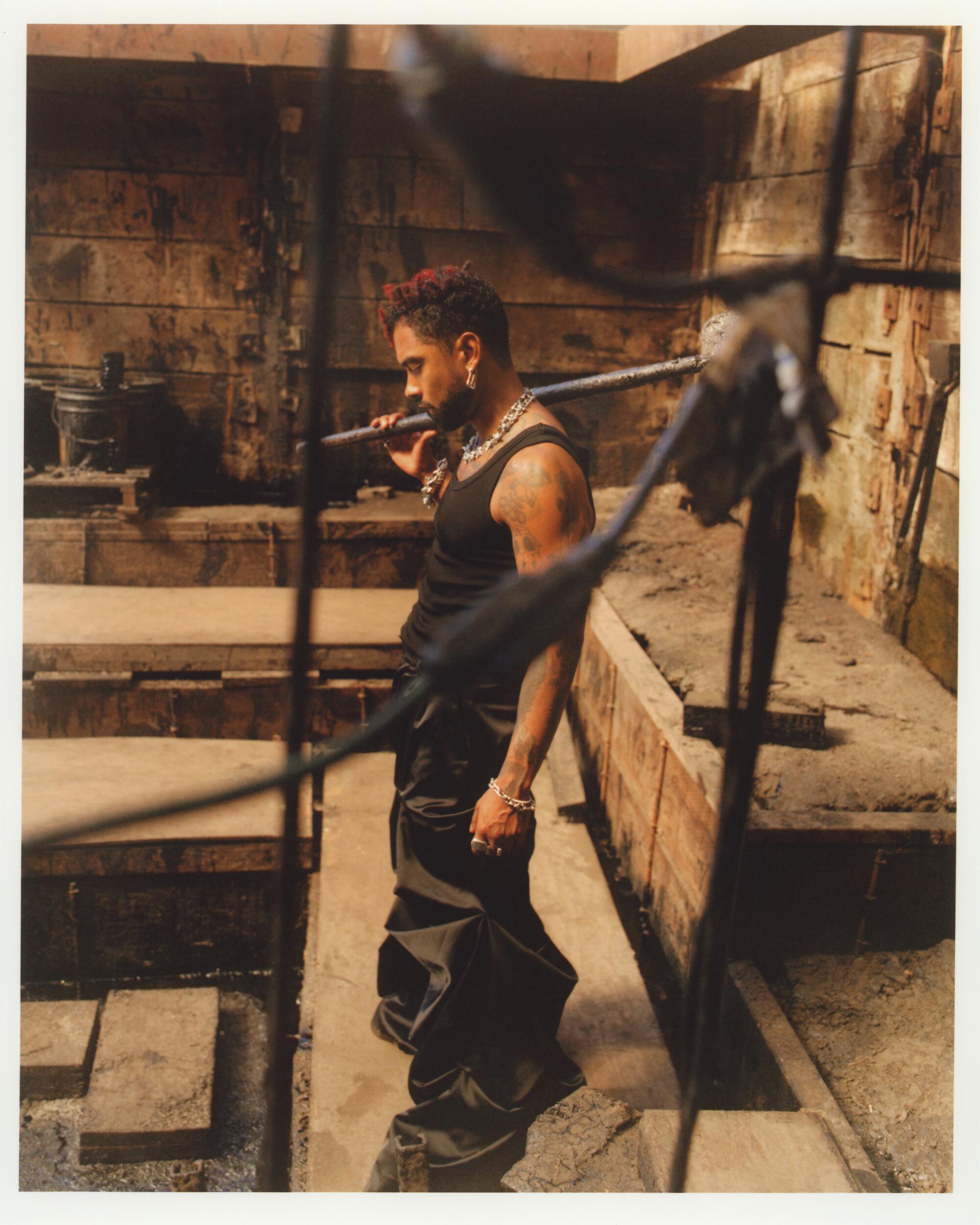

When I meet Miguel at the Cara Hotel in July, he’s wearing Y2K-inspired Balenciaga sunglasses, with dip-dyed red locks and chipped black nails. He has a silver briefcase next to him, and he won’t say what’s inside. Miguel’s personal style right now feels like a reflection of where he is mentally. “I love edges and I love curves,” he says. “I want to feel dangerous, and I also want to be supremely comfortable.” For the last few years, the singer has only been getting deeper into a look that might be described as goth casual: a lot of silver jewelry, mostly black, Balenciaga, leather. He just got back from Paris fashion week, where he watched Pharrell’s debut show as Louis Vuitton’s creative director and walked the Marine Serre show in a glossy black suit and shirt.

He tells me this is his first sustained period of being alone since he was a teenager. He’s been trying to force himself to try new things, to employ the Zen Buddhist concept of beginner’s mind in the hopes that it might be able to rewire his brain. In doing so, Miguel is trying to build an identity for what is clearly a new epoch in his life. It has been weird, he says. He’s been falling down YouTube rabbit holes on quantum jumping. He now legally owns five guns that he felt drawn to as a means of self-protection and a deep mistrust of human beings that was triggered after seeing George Floyd killed: “It changed me.” He can also laugh about things he’s been through that previously might have him to feel some type of way.

DJ Quik discusses legacy, L.A. music, Death Row records

One moment happened 10 years ago. Back then, he had only two albums under his belt and was still wearing skinny suits. But an ill-fated leap over the crowd at the Billboard Music Awards that year — where, during a particularly feverish performance of “Adorn,” Miguel attempted to crowd surf over a cluster of people and landed crotch-first on one woman and kicked the other one in the head — felt like the end of the world. “I was such a different person at the time and it meant so much more to me — it was massive,” he says. He was wearing customized Yves Saint Laurent Chelsea boots. “I should have worn Jordans.”

And while theorizing that the outcome could have been different with alternative footwear makes him laugh, he knows that it was part of being a risk taker. “Listen, I will go for it — that’s who I am,” he says. “Sometimes you go for it and it just doesn’t work out. And that was one time it did not work out.”

Everything feels deep when you’re 27 (especially an incident that gets immortalized in memes for years to come and two years later gets you sued). And Miguel was at a place in his life where, two months fresh off the win of his Grammy, he felt like he owed something — an explanation, an apology — to everyone. He thinks less about the fall and more about ascension these days — about how to see obstacles and find his way through.

Back at the climbing gym, Miguel observes as his instructor shows him some possible tricks that might be able to help him get to the top. She makes it looks easy. He’s impressed by her ability to scale the wall like a dexterous koala. He quotes a Charles Bukowski line he often cites to her: “To do a dangerous thing with style is what I call art.” When it’s his turn, he rests his left foot on a foothold, his left hand and right hand on a diagonal from each other, but his right foot is dangling. This is where he’s been getting tripped up, forgetting, at a slant in the sky, that there is another foothold only a few inches from him that is going to be crucial to get to the next step. While there is a sense of tension, there seems to be no fear.

This is also where he stands mentally: Having experienced the most spiritual growth of his life in the last year, he has reached a place where he is more dedicated to the process of making work than the anticipation of how it will be received. (“I’m f—ing 37. I don’t have the energy to be nervous anymore.”) He is embracing the novelty of being solo. He is stretching far beyond the expectations people have placed on him. Mostly, he is moving without trepidation.

He considers some of the wisdom from earlier in the day. In bouldering, there are several essential truisms one should remember. Looking down before trying to hit the next step is critical — what is behind us that could get us to where we’re going? The other is trust of self. As Miguel dangles 15 feet in the sky, he glances down, and suddenly a light goes off: His right foot makes contact with the forgotten foothold and he launches toward the top. Problem solved.

Producer: Siya Bahal

Grooming: Amber Amos

Tailoring: Ryosuke Igarashi

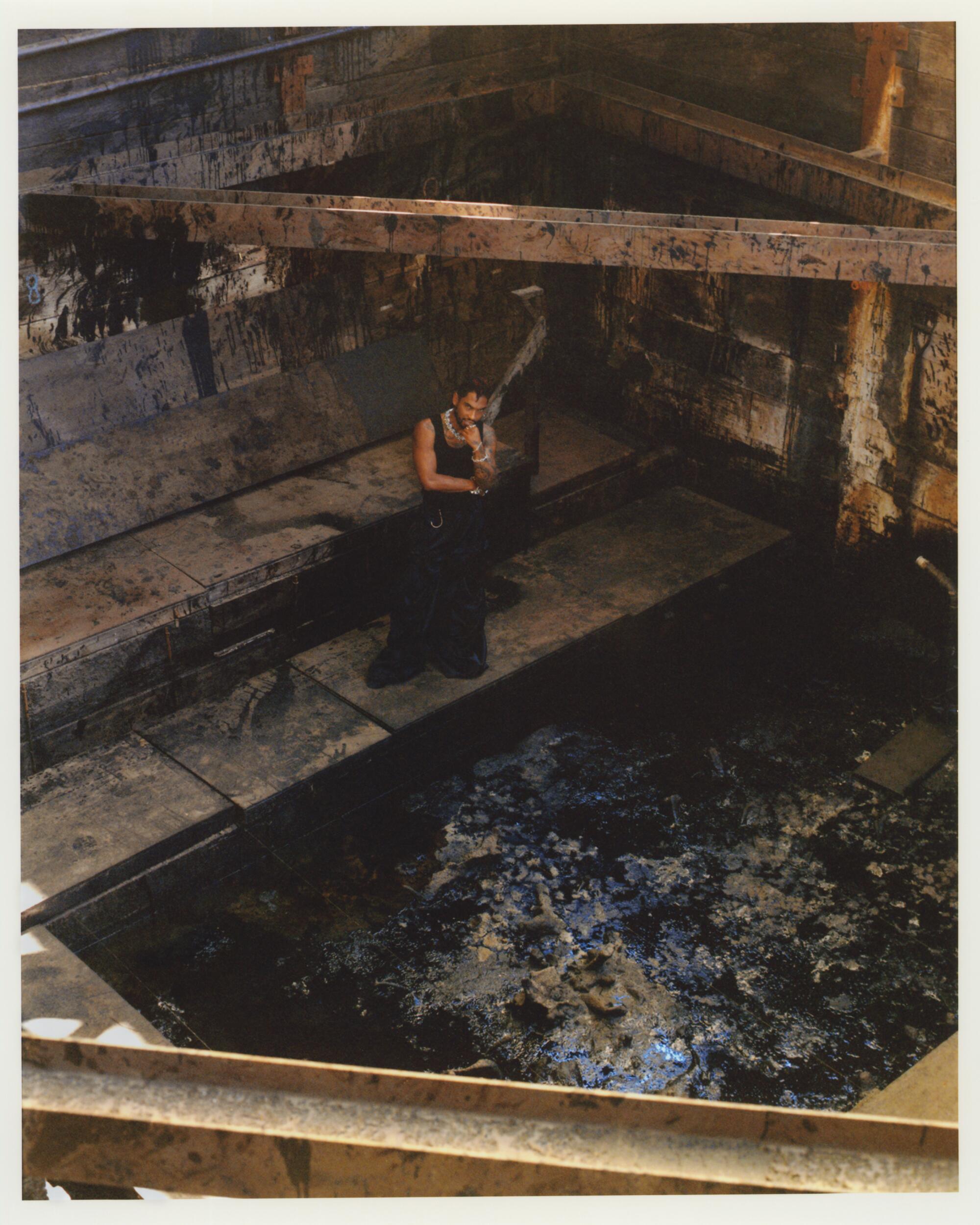

Location: La Brea Tar Pits