- Share via

This story is part of Image issue 18, “Mission,” an anthology of fantastic voyages — from L.A. to the world and back to the epicenter. Read the whole issue here.

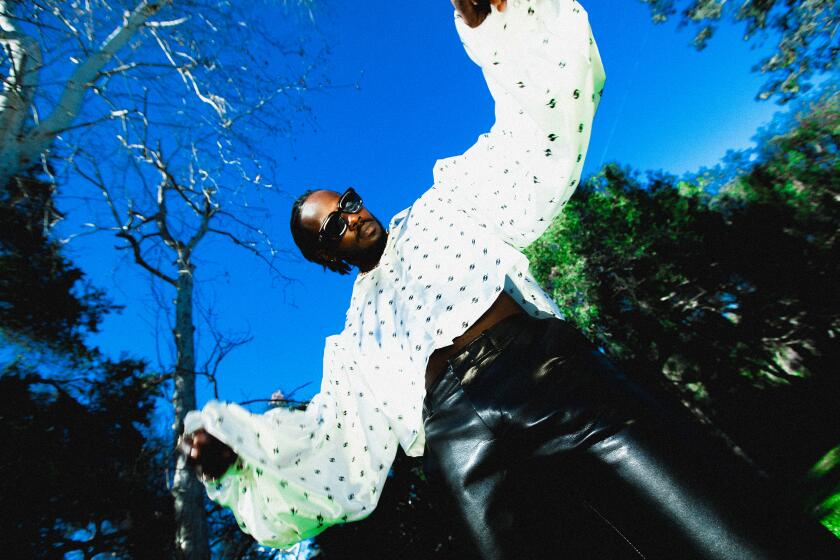

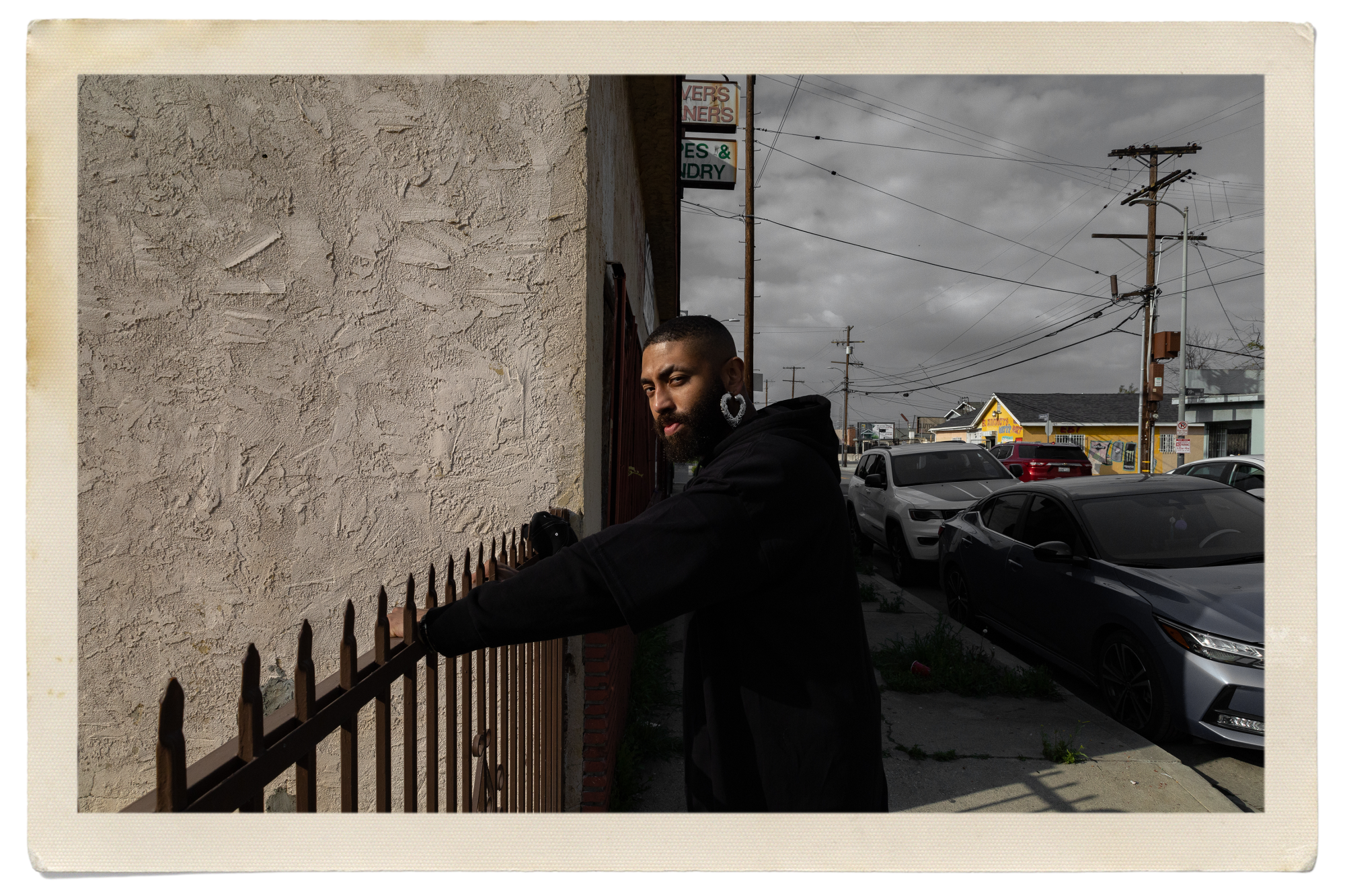

Walking down Compton Avenue and Century Boulevard, you feel a movement that is hard to place. A massive tree is at the intersection, its roots gnarled and twisting. A group of teens strolls by, excitedly recapping some private story. Two friends catch up in the parking lot near the tree. When artist Rush Davis arrives, dressed in black, the alchemical sign for Mercury shaved into the back of his head, he too seems to be moved by the cadences of this intersection, becoming another element of its bustling energy.

Davis — a singer, producer, DJ and creative director whose style traverses house, techno, R&B and more — grew up on Compton, in the second house on the block, right next to a laundromat. He has been down these streets many times. It is an environment awash in memories. He points to a church on the other side of Compton Avenue. “I was baptized there.” Born in Louisiana, Davis moved to Watts when he was 7, living with his extended family, including his grandmother. Davis, who is Black and Mexican, credits his family’s wide taste in music as an early influence on his own style.

“Feel the pressure, embrace the lesson / Be confident, be confident,” Davis sings on one song from “Transmission,” his 2021 collaborative album with producer Kingdom. These lines seem to infuse everything he does, whether it’s serving as a creative director for artists like serpentwithfeet or producing his own tech-drenched R&B reveries. Throughout his projects, Davis brings a sense of play and risk that honors the experimental spirit of the L.A. queer communities that shaped him. For Davis, creativity feeds off this willingness to be open and vulnerable with others. His desire to connect is felt in his crystalline voice on songs like “Love Is Blood,” which bends and snaps his lyrics toward new horizons of sound and emotion. His music pushes us toward other worlds, ones that embrace what Davis calls “the nuances of things.”

With a new EP and outlook on life, the L.A. artist is reaching toward his truest self.

Allison Noelle Conner: Why is the intersection of Compton and Century meaningful to you?

Rush Davis: Compton and Century is my heart. Many generations of my family grew up here at 9917 Compton Ave. My grandmother worked at this laundromat [next door]. This was the only consistency I had growing up. My parents moved around a lot, and then at 15, I got kicked out for being gay. So I’ve lived all over Southern California. But this was the only place that was home. This was the only anchor I could keep coming back to.

ANC: How did this location shape your interest in art and music?

RD: I come from a really big family. My great-great-grandmother had 20 kids. At any given time, there were anywhere from 10 to 15 kids in the house. I’ve been obsessed with perspective since I was a kid, so music was the biggest insight to people’s minds and emotions and what they were going through. I could tell by the certain music people would play what was going on with them. And that’s really where it started. Because everybody in my family is into music, we connected over music and there was always music playing. Whether it was my grandmother, playing [things like] Paquita La Del Barrio and the Isley Brothers, or my mom, who was really into hip-hop. It was all these different colors to paint with. It was always around.

ANC: You were also exposed to different music at Mustache Mondays. Could you talk about why those parties were a turning point for you?

RD: Mustache was the first place I went to where the true “other” was celebrated and platformed.

Before I found Mustache, I was going to clubs in West Hollywood. Those were predominantly white spaces that celebrated the white form in a lot of ways. And I didn’t see myself anywhere. Then, when I did see myself — say, for instance, when they had a Black night on a Sunday — when I would be in that space, I was like, I still don’t really fit in here. Because the way I grew up, I’m into house, I’m into tech, I’m into gangsta rap, I’m into all of that.

When I saw the people that were getting platformed [at Mustache] I was like, “Oh, whoa, this is home.” It was the first time I ever felt that way in nightlife. I used to walk out of this house, go straight down that way, make a left on 103rd Street, take the train, and go all the way to downtown L.A., hop off over there, walk down 4th to La Cita [on Hill Street]. This was my path.

The L.A. artist taps into the ways in which God shows up, and how to honor that in real time.

ANC: Mustache stopped in 2018. Do you still feel that time is influencing what you do now?

RD: Absolutely. You are what you eat. I believe that completely. In terms of my DJ style, and the type of music I produce, I was definitely fostered by listening to resident DJs like Josh Peace, Total Freedom, Kingdom, Asmara and Daniel from [the duo] Nguzunguzu. When I would hear a crazy ass blend of a Mariah Carey record over some crazy tribal-like, industrial tech type s—, I was like, “OK, whoa. This is the music I want to hear.” Because it’s borrowing from everywhere. But it’s fractal and kaleidoscoped into all these different vibrations that really speak to me. I try to carry that on when I play.

Most places I go to can be very genre specific. They either want to hear hip-hop or tech or house. Or they want to hear R&B. But for me, it’s like, “Nah, you’re gonna get what I feel, right? And we’re gonna go on that journey together. And hopefully [you’ll] leave a little bit more exposed.”

ANC: You’re part of the House of Xtravaganza. How did ballroom culture open up your sense of who you are as an artist?

RD: In short, language. It gave me language. I didn’t have an understanding of who I was because there weren’t clear examples in the public or media. It wasn’t until I went to a ballroom and I saw the category “Realness With a Twist,” I saw thug-looking n— come out, you know, get their 10s for ‘realness,’ then come back out voguing. I was just like, “Oh, s—. That’s me.” You know, that was the first time I ever saw that.

ANC: How old were you?

RD: I was 16. I first started going to the Arena [club] in Hollywood. That was when I first got exposed to ballroom. Around that time, I met some people from the [House of Prodigy, an international ballroom house founded in 2002 and based in Philadelphia], and they brought me shopping with them, to get ready for a ball. And one of them was a sex siren and another one was drag. This is the first time I was ever out in public with gay people. We were in Santee Alley downtown. My homie Sammy was trying on thongs. And I was like, “Oh, my God. I’m just fully out in the world, in daylight.”

ANC: What’s your relationship to ballroom now?

The queer, Latinx songstress San Cha tells Suzy Exposito how she achieved enlightenment by learning to create art from a divine place.

RD: I stopped walking balls when I was like 24, 25. I started focusing on music heavily because I realized that in our house alone, there were so many artists. And I realized the best thing I could bring to the house was everything that I am. And what I am more than anything, outside of the ballroom, is music. I make music. I try to give my sisters and my brothers from the scene really good music.

ANC: You released two albums with Kingdom last year. Did Compton and Century play a part in the creative process at all?

RD: Me and Kingdom’s relationship goes back to Mustache. In 2019, he sent me a pack of beats. And one of the beats he sent was for “Love as Blood,” [a single from the 2021 album, “Transmission”]. I was walking from the liquor store, and I just started bawling because I was thinking that this is my friend and my friend made this beat, and this is literally one of the craziest things I’ve ever heard.

To touch on how [Compton and Century] weaves into all this, what this place gave me was an openness to reach out and a boldness to let people know where my heart is and where I stand. And from that boldness, I was able to tell my friend, “Hey, look, I know we’ve been working together for years, but I think we should do a collaboration project because these past few tracks you sent over, it’s feeling like a thing.”

This place is character development like no other. This place gave me antennas. This place gave me a sharpness and a nimbleness. It taught me how to move through the world, to ask for the things I want and claim the things I know are mine.

ANC: You’ve also worked with musicians and artists Dawn Richard, serpentwithfeet, Shaun Ross, among others. Could you describe your approach to collaboration?

RD: The collaborative process is how you bring worlds together. It’s how you turn one room into many rooms, you know, it’s how you turn an apartment into a mansion. That’s the thing about collaboration. It’s a bridge for me.

Also, I think the crux of my career has been collaboration. And I call it a crux, a cross, because it has revealed me. I don’t think I would have been in any of the places that I’ve been without having artists champion me and allow me to step in and help them steer their vision or give them insight or language for what they were trying to do. And that goes for many different forms of collaboration, not just on the music side but also on the creative direction side, on the directing side. All those things are aspects of collaboration for me.

Not much documentation exists about the voice of the barrio. So artist Gary Garay dug deep in the crates to fill the void.

ANC: What does your community mean to you?

RD: It’s interdependence. For me, the most powerful position to be in is in the space of mutual need. I need you and you need me, and that’s a good feeling. It’s a great feeling to know if I need [something], I know who to call. And to know that there’s not this feeling of a side-eye or anything, but that we’re both feeding each other. That’s really what our community thrives off of. Like the Mustache family. There are so many powerhouses, in terms of perspectives and tastes and reach and resources, that when we come together, anything is possible.

ANC: What are you looking forward to?

RD: I’m actually working on my first [solo] album; I’ve been working on it for a while. Before I put that out, there’s going to be a slew of singles with a bunch of different artists that I love to create with.

And then the biggest thing is, I want to spread energy around the world. The most important focus for me right now is getting out into the world and DJing and performing in front of as many people as possible. I just need people to feel it.

Allison Noelle Conner is an arts and culture writer based in Los Angeles. Her writing has appeared in Artsy, Carla, East of Borneo, Hyperallergic, KCET Artbound and elsewhere. Currently, she is the editorial fellow at X-tra Contemporary Art Journal.