- Share via

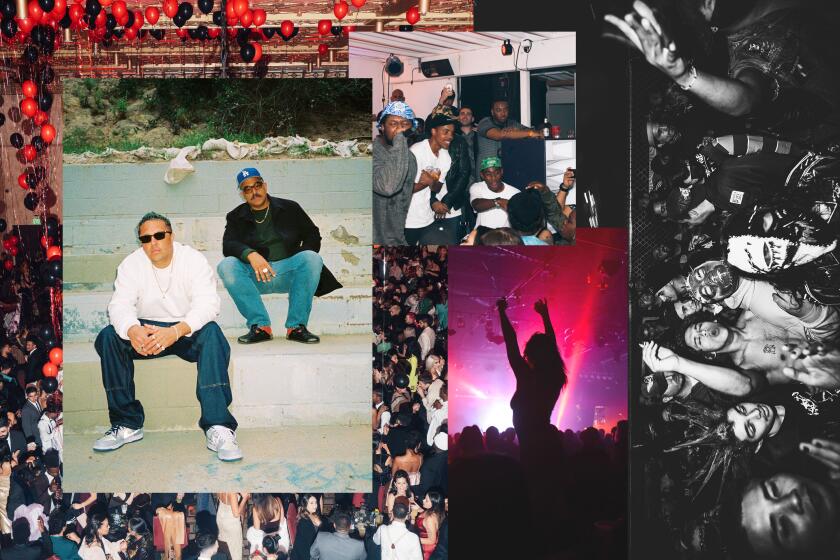

This story is part of Image issue 9, “Function” a sonic and visual reminder that there ain’t no party like an L.A. party. Read the full issue here.

Growing up Japanese American in Los Angeles is like a scavenger hunt to find your kin, histories and stories. You have to first wade through the history of the Second World War incarceration and plunder to discover that even less documentation exists about our community beyond these traumas. Artist Alan Nakagawa is a conduit for these joyful stories. For decades he has been rethinking how archives and oral histories are used. He unearths and unpacks forgotten histories through meticulous research and his expansive, multidisciplinary artistic practice. As an oral historian and sound artist, he is interested in what the past and future sound like — he’s curious and patient, generous and meticulous, a true practitioner of paying it forward.

It’s no wonder institutions like the Smithsonian, Japanese American National Museum and CSU Japanese American Digitization Project are partnering with Alan — he is a connective tissue, one who locates, anchors. He mends together disparate experiences to strengthen the tapestry of the whole. “I’m constantly thinking about time as a multi-existence reality,” he told me.

Alan is also a mentor, friend. My work as an artist, academic and organizer has been influenced by his generosity of mind. Working outside of the mainstream commercial gallery economy, Alan has created an alternative career model for artists that doesn’t include selling objects. He has taught us how to be a partner in civic and community improvement, and how artists can work with institutions to disrupt and alter the way they serve the communities they exist in.

We met while riding bikes, exchanging family stories about being an artist and growing up JA (Japanese American) in Mid-City. Since then, a few times a year he invites me over to his studio to hang out. Our conversations are always two hours longer than expected and include some kind of unique meal with a layered story at every bite. During our most recent hang, he served me a homemade lemon tart and cup of tea in a ceramic mug made by terra-cotta clay artist Wayne Perry. Always giving. Always Alan.

Devon Tsuno: I remember my father telling me when he first moved into this neighborhood — Koreatown, Mid-City — there were a lot of Japanese American folks. But now, I think most people in Los Angeles don’t really think of this area as Japanese or Japanese American.

Alan Nakagawa: You’re talking about the ’60s and ’70s. I was born in ’64. That moment was sort of the apex of Japanese people moving into this general area — from here to Crenshaw, what is now Martin Luther King [Jr. Boulevard]. Maybe even into Leimert Park, but not quite Leimert Park. Where all the shops are. Leimert Park certainly from Rodeo — [now] Obama — to Martin Luther King and Crenshaw, that area used to be all Japanese. And there’s still a lot of Japanese people who live there. Elizabeth Ito, the amazing animator. A lot of those houses — around Crenshaw, Martin Luther King, Obama — still have the Japanese bonsai-looking plants in front, even though the people who occupy the houses are no longer Japanese American. They, for one reason or another, have embraced the Japanese landscape. Those are remnants — clues — of my childhood.

We never said “Mid-City.” We would always say “Midtown.” Nobody calls it Midtown anymore. That’s not even on the map. There used to be a lot of Japanese families. In fact, the famous actor Mako, one of the founders of East West Players. He did many roles in his multidecade career. He did the voice of the rat, father, teacher in the original “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles” — the movie, not the animation. He used to live right across the street, down the block. When I was growing up, that was a big deal to have an actual Hollywood actor in the same neighborhood.

There used to be this green truck that would show up once a week. Just a regular van that you could actually walk up into. It had refrigerated counters and cabinets. And it sold Japanese food. This is before any of the Japanese markets.

DT: Like an ice cream truck?

AN: It was like an ice cream truck but get rid of the ice cream and put Japanese food.

DT: When you bring up the grocery truck, I was wondering if there was any community-building for Japanese folk in a space like that?

AN: For the regulars, there was probably a sense of community.

DT: Your family had a restaurant, Beni Basha, really close to here. How did that fit within the ethos of Koreatown and Mid-City as most people know it?

More from The Function

Jason Parham talks to DJ Quik about his legacy

Born X Raised takes you inside the most epic ragers in L.A.

Julissa James dives into the subconscious of indie-pop prodigy Hana Vu

The homies let us know what makes an L.A. party an L.A. party

Gary “Ganas” Garay searches for the forgotten voice of the barrio, Jonny Chingas

AN: When it gets brought up that my family owned that restaurant, it’s usually met with very, very fond memories. There were several Japanese restaurants. But I believe ours was one of the most popular ones. We actually got write-ups. Not write-ups in the L.A. Times; back then we had the Herald Examiner, Japanese magazines and the local Japanese paper.

DT: I think that a lot of these stories you’re telling me are really important stories about the cultural fabric of Los Angeles, about the people here, about all this history. But when we think of what’s in an archive and what’s normally valued, you don’t learn about the green truck selling Japanese food. That’s information that isn’t documented.

AN: It’s not. I would like to document that somehow.

DT: Can you talk a little bit about your general approach to archiving?

Producers, promoters musicians, artists, DJs and others share their favorite L.A. party anthems, plus the memories surrounding them and their thoughts on what makes a party hit.

AN: Let’s start with growing up in this community. The community I grew up in was more Japanese than it was Japanese American. There were Japanese Americans, obviously — many of them were born here; some of them were in the camps — but most of my family’s friends were Japanese immigrants. They came here right after World War II. So there’s a richness that I constantly tap into that‘s like a flame that I try to keep alive in my life. It’s everything from the language to the food to friends and family in Japan.

My art training started with Shizue Yamashiro. She happened to come to Los Angeles with her husband. She’s part of this Abstract Expressionist group of Tokyo. And I guess she put an ad in the Rafu Shimpo and said, “I’m starting art school for kids.” I start when I’m like 9, and it’s her apartment on Keniston Avenue, near L.A. High. Every Saturday my mom would drive me there. We started with oil pastels. Pentel oil pastels.

DT: Wow! My grandma used to give me those oil pastels. I didn’t know that was a thing.

AN: I’m bringing her up because — I wasn’t aware of it at that moment — in hindsight, it was really important to have a Japanese mentor. She’s a professional painter. She shows, she teaches, she’s respected amongst the community. And then she often talks about her community — like, here’s so-and-so from Japan.

As I get older, she starts to realize, Oh, this guy might actually want to become an artist. So she says, “You should go to Otis because my friend Mike Kanemitsu teaches there. And he’s really well respected.” I applied for Otis and got in.

DT: When did you start there?

AN: I started in 1982. But Mike was not there anymore. Mike had retired. I was like, Mike doesn’t teach here anymore! And then my friend invited me to a dinner at Mike Kanemitsu’s. His son, Paul Kanemitsu. He was good friends [with] — that’s where I met — Gajin Fujita. They were kids. They were in high school doing spray-can art. That’s why eventually, Collage Ensemble Inc. publishes that video [in 1997]: “L.A. Hip Hop Video Volume One.” Because of Paul and Gajin.

DT: I’m still waiting to see that.

AN: It’s very short, like 30 minutes. But the who’s who of that time of spray-can artists are all there. I think the most important thing about that video is Carmelo Alvarez. We interviewed him and he talks about Radiotron. Do you know about Radiotron?

DT: No. Tell us about Radiotron.

AN: In the early ’80s, right when I’m at Otis, Radiotron is opened by Carmelo and his friends across the street. Kind of near where Chouinard used to be. It was a big building with a huge basement. Carmelo’s friend either owned the building or managed the building. And he was like, “Carmelo, I got this empty space. You want to do something with it?” He says, “Can I start a youth center?” And the youth center turns out to be Radiotron.

During that time, hip-hop starts to creep into the culture. And Proposition 13 had been passed maybe four or five, six years before. By that time, all the muscle that Proposition 13 pushed is already part of the culture: the lack of services for kids, all of the after-school programs at the public libraries are all gone. And then kids start to latch into breakdancing. One kid — out of hundreds of thousands of kids breakdancing — cracked their neck, maybe severely. The City Council passes an anti-breakdancing thing for LAUSD. Like no one could do breakdancing on school property anymore. There’s all these anti-youth things happening. So when Carmelo opens Radiotron, it’s one of the only places — or perhaps the only place — where you could learn how to pop, spray-can, break beats. It’s completely avant-garde at that point. It’s really when it’s all starting to bubble up to the popular surface. And in our little video Carmelo maps it out. There’s a really young Laurence Fishburne — he’s a bouncer at one of these hip-hop places. This is something you never hear about.

“I’m constantly thinking about time as a multi-existence reality.”

— Alan Nakagawa

DT: When you’re telling me this story about how the L.A. City Council police the solidarity between our two communities through these urban forms of creative expression, music and art and dancing, it’s disheartening. But it also makes a lot of sense — those types of things are still happening today. Politicians and police are definitely still finding ways to police us and to keep these type of energies outside of institutions like LAUSD.

AN: I mean, what’s the difference between that and the sign at public parks, where they say no skateboarding? The bigger message is no kids allowed, youth don’t count.

DT: It’s cool to learn about cultural organizing back then. When you tell me these stories, I’m like, that’s why it’s like that. But I think we should talk about the archiving part too.

Buy a copy of Function

It’s true what they say: ain’t no party like an L.A. party. Image magazine is back with Issue 9, the first issue of 2022.

Shop the L.A. Times Store

AN: OK. You want to talk about archiving? Having mentors who look like you; being in situations where it’s more multiethnic, for lack of a better term; the sort of inclusivity that has to happen if you’re going to get access to broad knowledge — having that base allows you to bring it to the next step. And so the next step is like, I know the stories of all my mentors. And so when I do something, it’s connected to their story. So there’s this idea that it’s not just me at this moment. I don’t think I could ever be an existentialist because I’m constantly thinking about time, as a multi-existence reality. Because it’s played such a part in my artmaking in my life, I think I’ve gravitated toward situations where the art is about history, or the art is about hidden history. That’s really important to me.

Whenever I give a workshop about oral history, I always say, “I am not interested in interviewing anybody who’s already been interviewed.” Then I go the next step and I say, “I actually hate interviewing people who are used to being interviewed.” Because their answers are usually canned. There’s nothing more frustrating as an oral historian than to get a canned answer to a question. My joy is when I discover something with somebody — discovering it together is the most tasty thing, the most creative moment.

I always go back to the one I did with Mike Winter, who’s an amazing composer, co-founder of the wulf. from CalArts. He did his performance, the crew left, and then he and I did an oral history session. About a week after that, he emailed me and he said, “Oh, my God! I’m still thinking about the interview. This one thing we talked about, I’ve never told anybody that. I never realized that had such an impact in my artmaking practice.” That’s what you want. You want that discovery, that level of discovery. There’s no point in interviewing people who’ve already been interviewed. I shouldn’t be so black-and-white about that. But as an oral historian it’s more interesting to find those moments. If you’re lucky, you actually empower the person you’re interviewing, because they find out more about themselves. And they anchor themselves to not just history but also their history. Whenever someone says, “Oh, no, you don’t want to interview me. I don’t have anything to say,” that’s probably the first person you want to interview.

DT: As an artist and as an oral historian, how do those things connect?

AN: Let me step back and say, I am not an archivist. I know archivists. I’ve met them. We are very different. Our motives are very different. And our needs are very different. Our intentions are slightly similar. But that’s about it. We’re definitely trained completely different. So I would never call myself an archivist. I’m an artist who uses archives. There’s a difference.

Now that I have had this fairly privileged life of training, I’m at that point where I want to celebrate certain things. When I discover an archive, when I discover history, or stories that I think are important — just like what you just said, “Oh, I didn’t know about the green truck.” I mean, the green truck is not going to change the world. But it anchors us — you and I as Japanese Americans — just that much more in our neighborhood. And that’s power.

Devon Tsuno is a multidisciplinary artist from L.A. He is an assistant professor of art at California State University Dominguez Hills, where he founded and co-directs the CSUDH PRAXIS art engagement program. He is represented by Residency Art Gallery in Inglewood and is a co-founder of J-Town Action と Solidarity. His spray paint and acrylic paintings, art books, community projects and installations focus on native versus non-native plants, water, labor, public space and Japanese American history. @devontsunostudio