- Share via

This story is part of our issue on Remembrance, a time-traveling journey through the L.A. experience — past, present and future. See the full package here.

... All this month I’ve

gone in search of the right cross, the punch

which had I mastered it forty years ago

might have saved me from the worst.

— PHILIP LEVINE, “THE RIGHT CROSS”

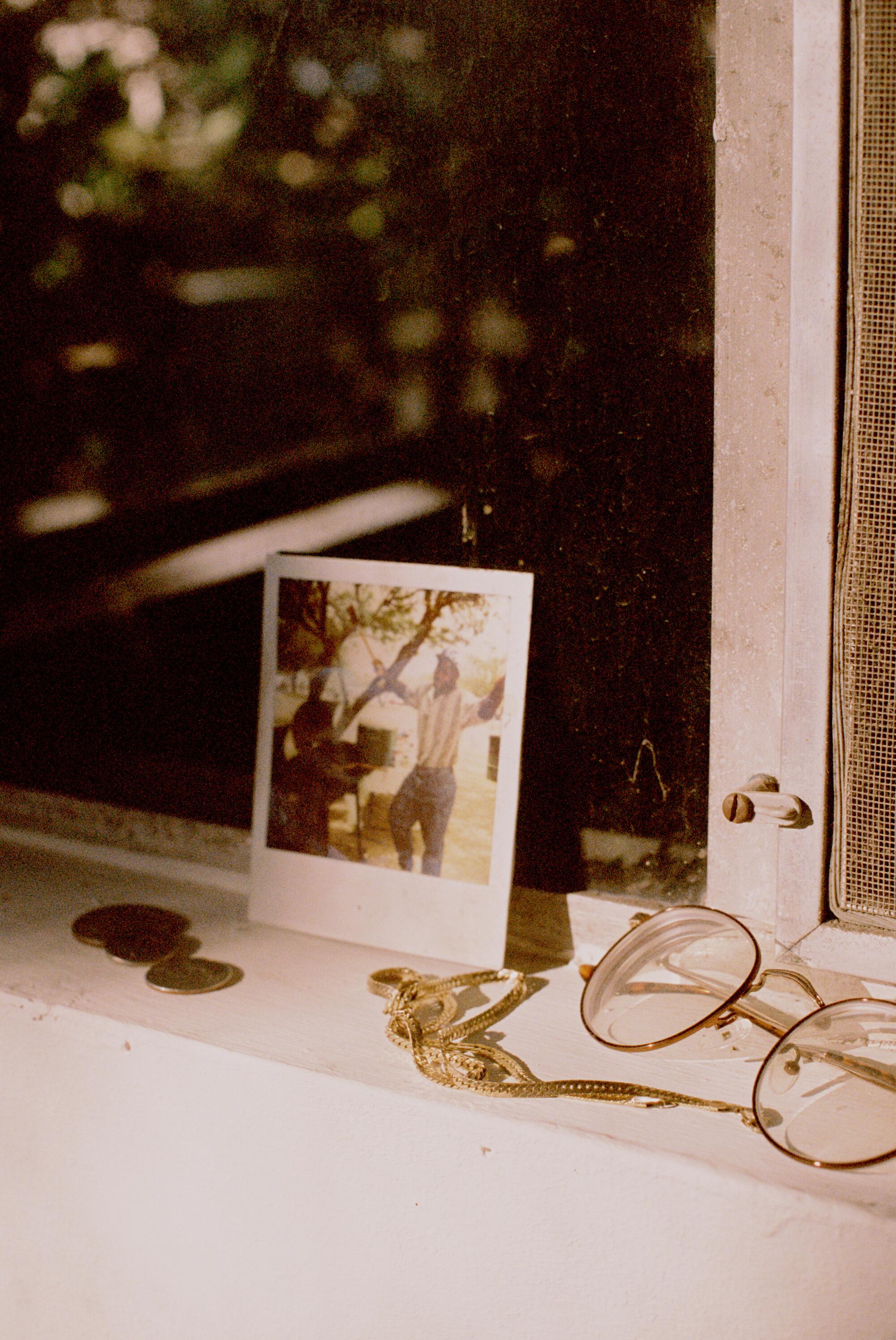

Today I found myself standing at the window, half in a dream, my hand at my neck, fingers searching absently for a cross I’d lost more than a year ago. This keeps happening; muscle memory. I’d worn and worried that cross back and forth on its chain for some two decades. Over time, I added two other gold chains, both of them gifts, but the cross I’d found, on the street, and managed to keep for 20 years. This is significant because I’m not a finder, I’m a loser. A chronic loser. A term I discovered only a couple of days ago, listening to the writer Adam Phillips give a talk on an essay by Anna Freud. A chronic loser constantly misplaces everything — watches, phones, keys, wallets, gloves, hats, sunglasses, eyeglasses. Sometimes they are recovered, mostly they are not. From what I understand, this is a symptom of altered libidinal processes; something misfiring in the deep, where desires are formed, making attachment difficult. Am I reenacting some infantile drama of neglect? Perhaps, who knows. But this made sense to me: In our attachments, whether to objects or others, there exists a continual fluctuation of our energies. We wish to possess, to be possessed, and to be relieved of our possessions all at once. The hoarder solves the problem of value and attachment by holding on. The chronic loser lets it all go. Not only do I routinely misplace everyday items but essentials as well; I’ve lost more than one passport, my birth certificate, Social Security card, numerous licenses, an entire library worth of books. None of these things were lost together, mind you, not all at once, in a fire, but one by one, piecemeal. I once left a laptop on a train, which contained the only copy of a manuscript I’d been working on for years. But never in all that time did I lose any of my chains, or my gold cross. Until one day, I did.

Only when the cross went missing did I even realize I’d held on to it. I hadn’t been careful, or clinging, or conscious of the value and meaning I’d bestowed. I simply never took it off. Now that it was gone, now that my fingers habitually reached up to play with it, and found absence instead, I came to feel the cross helped me to think, and daydream. I realized, too, how ridiculous this was; I’d never considered myself a fetishist, but as it turns out, I’ve got a thing for chains.

My father was a man who both did, and did not, wear chains. I must have been around 8 years old when he found work which, for various reasons, involved him accentuating his “roots,” by which I mean, it was necessary and expected of him to perform a kind of ghetto authenticity; to speak Spanish and Spanglish and jive with the older generations and a less poetic, more vulgar contemporary slang with the young ones; to embody the intimidation and charm of a gangster. His work car, which my brothers and I loved to sneak inside, had tinted windows and was pimped, as we said at the time. My father was not an actual gangster. In his home life, and in our white working-class town, he was aspirational, busy elevating his station, keeping up with the neighbors. He left the house and returned dressed like all the other dads. We rarely saw him in his work costume. Only on the rarest of occasions, for reasons unknown to us, would he break out the flash: the diamond stud earring, the gold chains, the gold cross, the medallions, the gold watch. (When alone in the house, I used to hunt for this jewelry, unsuccessfully. Eventually, I gave up, assuming it must all be kept in the lockbox under the bed, next to his gun.) He’d sag his jeans, and we’d imitate his strut. “Put some stank on it,” he’d say, and we’d try and mostly fail. The persona that floated up to the surface in those moments was uncanny, this other, gangster father, drawn from both stereotype and some mysterious essence he kept hidden from us. Upstate, I was used to everyone projecting cool onto my father, no matter how corny he might act, due simply to his Brooklyn accent and brown skin; but in those moments of transformation — in the flash of the flash — an actual, almost tangible coolness radiated, emanated from inside.

This story is part of our issue on Remembrance, a time-traveling journey through the L.A. experience — past, present and future.

My father was a proud man, and moody. He could be sentimental, loving, hilarious, but he could also explode into violence. My mother explained this had to with the prejudice and indignities of poverty he’d dealt with in childhood. Explaining away the “bad father” and redirecting us toward the “good enough father” was one of my mother’s covert responsibilities. Yet whatever or whomever flashed in these moments, when he wore the charms and called forth this other persona, with both self-mockery and reverence, this trickster figure, hard and cool — well, I did not want this man explained away. I wanted him to stay. And to my child mind it seemed the charm of the shadow father had everything to do with all that bling, with the charms themselves, the most mystical and magical of all, which I was not allowed to wear, or handle, being the crucifix.

Then two, maybe three years later, something happened both mundane and terrible, which altered my relationship to this form of ostentatious, hardened masculinity. Here’s the memory, present tense: We drive down from our home in the boondocks six hours south, making the pilgrimage to the three-bedroom Brooklyn apartment where my aunt and uncle and abuela and five cousins all live. Other tíos and cousins are there when we arrive, and more shuffle in behind us. It’s crowded, loud, the air thick — people still smoked indoors back then. I’m forced through hellos, reintroductions, prods to speak up; I’m shy. On the living room floor the younger cousins press up close to the television, watching cartoons, which they turn louder and louder to battle the noise. Commercials play for toys and sugar cereals. I want to join the little ones, though I’m too old to do so unselfconsciously, so I inch closer and closer, when in walks a young man I’ve never seen before. He’s beautiful. Apart from the uncles I know, in Brooklyn there are always new men, second cousins, half-siblings of half-siblings, somebody’s boyfriend, who are introduced as “uncle” so-and-so. I don’t remember this uncle’s name or relation, only that I never saw him before, and I never saw him again after that day. He is beautiful. The soft luster of his skin only accentuated by his rather severe nose and brow. Everything is crisp: his fade, the lines shaved into his eyebrows; jewelry glints all around him, a diamond stud earring, chains, a gold watch worn loose. So beautiful the men are unafraid to acknowledge the fact, as they do now, whistling through their teeth and naming him pretty boy. He is probably only a teenager, but he very coolly makes the rounds of handshakes, daps, and benedictions. I stare, nakedly, as he unzips and removes his jacket. Underneath is a T-shirt printed with a cartoon rabbit, whom I recognize as the mascot of the kids cereal, Trix.

Silly Faggot, the shirt reads. Dix are for chix.

I don’t gauge any other person’s reaction, though it’s safe to assume some laugh and some chastise. This is the very early ’90s. What do I know then? I know that the hatred of faggots has to do with AIDS, and in a deep and unformed way I know that the hatred of faggots has also to do with me; I know it is time for me to leave the world of cartoons and sugar cereals, and I am embarrassed by the fact that I am not ready, that I keep looking backward. I know that it feels dangerous, now, to look at this uncle, but still, I want to. I force my gaze into the middle space, below his eyes and above his message, where a crucifix hangs — and it’s an exact replica of the one my father keeps hidden away somewhere in the house. That’s the point of fixation, where the memory short circuits, overloaded by the sudden double awareness of something burning in me, and a new depth to the ugliness burning out there, in the world. The memory ends.

How do we survive our own ambivalence? One way is to fetishize. Perhaps the chains, and especially the crucifix, became totems, able to neutrally absorb both hatred and desire. Perhaps in their glimmer and weight I saw a reflection of all that I wanted, and all that I feared. I don’t know. I certainly didn’t think any of that at the time. My parents divorced, and I lost my father, a gradual process that was pretty complete by the age of 18; I was doing everything I could to shake my mother. That Wildean quip comes to mind: “To lose one parent may be regarded as misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness.” I was careless with my life and their care for me, and things came to a head in a dramatic rupture, until finally I left for the city, where I was very much alone, and very broke, and then one day I was mugged.

Another memory: I’m walking down some Chelsea block with a friend, heading home from a club called the Tunnel. This would have been September 1998, coming on 5 in the morning and still very dark. The kid has a knife. Other club-leavers mill around, though no one intervenes. The kid has a knife, but he’s shorter and probably younger than my friend and I. We must have looked like easy marks, vulnerable, newbies to the city, 18 and piss drunk. We laugh, partly out of a kind of nervous terror, but also because we have nothing to offer up. I turn my pockets inside out, my friend opens her purse and pulls out various objects, a lipstick, a wad of tissue, and just keeps repeating, “Look, I have nothing. We have nothing.” Neither of us have credit cards, or even wallets or phones. (No one carried phones in those days, at least no one like us.) Even our IDs are fake, we’ve left our real ones at home. We’d had just enough cash for the cover charge and had spent the night downing the dregs of others’ abandoned drinks. The club kids ignored us, they were all so sophisticated in their debauchery; we were bumpkins. “Bumpkins but not for long!” we had vowed, yelling into the night, stumbling down the sidewalk, into the tip of the knife. I don’t remember the mugger’s reaction, I don’t remember how we got out of it. The memory ends with the image of my friend squatting, crapulous, and dumping her purse on the sidewalk. “I have nothing. We have nothing,” she says. And it’s true.

A couple of days later, I found the gold chain with the gold cross on the sidewalk, in a kind of reverse mugging, a gifting; the city, it seemed, might make or unmake, possess and dispossess at will, but would never leave me alone. At the time, scrawny as I was, my uniform consisted entirely of printed secondhand T-shirts from the boys’ section, usually with messages about Little League or summer camp or, ironically, D.A.R.E., and I began to wear them inside out, which I believed made me look more mature, and better displayed my gold necklace. I never took off the cross, not to shower, and certainly not when — as finally, finally, began to happen — men picked me up in bars, and brought me home for sex.

The very first line of one of my short stories — the first piece for which I was paid real money — begins with the main character, a young hustler, finding a golden chain on the ground. I was 30 years old when I sold that story and I used the entirety of the money to buy a designer suit, Prada. I wanted something extravagant and utilitarian; something that would help me transition into adulthood; something that would last. I lost the suit within a week. That year, for my birthday, my boyfriend bought me a silver feather necklace. (The necklace in the short story had been a feather, not a cross, though gold.) It had to be gold, it’s always had to be gold, but of course I couldn’t tell him that. I lost it.

But the loss I’ve been trying to figure out is the loss of the gold cross. So here’s a final memory: I’m 38 now, my man and I are on vacation in Berlin, staying in a hotel room with too many mirrors, two of which face one another on the bias. Walking in one afternoon, I’m startled by my own reflection, only from an angle I’ve never seen before. By this time, along with the gold chains, I’ve added other adornments, everything plated, gold wire rim glasses, and an inexpensive gold watch, worn loose. Recently, billowy short-sleeve button-up shirts have come back in style, and the one I’m wearing looks very much like the guayaberas worn by the older relatives. My forearms are tattooed.

“Jesus,” I say. “For a second I thought one of my uncles was in the room.”

“What, you mean in your reflection?”

I lean into the mirror, looking at the doubled image, turning and inspecting as one does in the barber’s chair. “The back of my head is … messed up.”

“No comment,” my man says, moving past me. He falls down into the bed, and is soon napping peacefully.

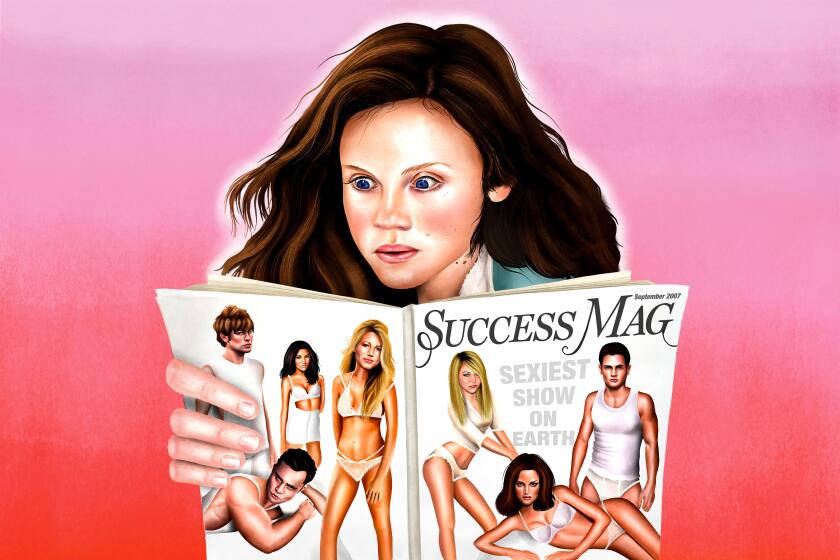

I thought I remembered why I didn’t get cast in “Gossip Girl.” But the truth was much more complicated.

Later that night we’re walking from one gay bar to another, drunk for sure, but not too messy, swerving a bit, talking in English, probably louder than we realize. Alone on a wide, brightly lit block, we stop, both of us looking at one phone, to make sure we’re headed in the right direction. When I next look up, two young guys stand before us, not two feet away, as if they had appeared from our shadows. They both offer greetings and smiles, ask us where we are from — the U.S., England — and we ask them in return. Another country, they say, originally, but they live in Germany now, in another city. English is clearly a third, maybe fourth, language; we don’t push for clarification.

Somehow, we make small talk, one is cute and the other just impossibly sexy. The cute one does all the talking, presses up close, flirts, and very shortly suggests we take them back to our hotel. We laugh. The sexy one is quiet; he seems to be largely just indulging his friend. He absently lifts his shirt and runs a hand across his body, up to his chest, down, tucks the thumb of his other hand into the waistline of his jeans. His body is more than a little distracting. I feel the shorter one kiss my neck and politely pull away. All the while a conversation is going on, the short one asking us questions, flirting, lightly fondling, and finally seeming to give up. He asks for directions to the bar we had just come from, which we show them on our phone. We part laughing, the four of us. We have no idea what they wanted. We have a hard time believing they actually wanted to sleep with us, especially the hot one; standard protocol would have been to just join us for a drink first, before proposing some kind of group hookup. I suggest maybe the short one is on ecstasy, or something, and his friend’s just along for the ride, he seemed sober. Certainly, more sober than we are. Whatever they were after, they took our rejection well.

It isn’t until we arrive at the next bar and order drinks that my man realizes all the money is gone from his wallet. Nothing else, no cards, just the cash. I have my cash — I always carry cash in my front pocket, and instinctively keep my hand on it when any stranger approaches (especially in gay bars and cruising spots) — but the gold chain with the gold cross is missing from around my neck. It’s all so clear in retrospect, the front man, standing slightly aloof, teasingly lifting his shirt and running that thumb along his waistband at porn-slow speed, while the other one, the cutpurse, worked us over.

“At least they were nice about it all,” my man says. We laugh and marvel at the dexterity, the Dickensian nimbleness of his fingers, this other, better, sense of digital theft. There seems something quaint and decent and forthright, and relatively harmless, about a good old-fashioned hug-and-mug. At that moment I don’t mourn the cross, I don’t think about how much time and meaning I’ve invested; instead, I feel something more beguiling, a kind of giddiness, relief.

“Really,” I say, “I was asking for it, with all these damn chains on.”

“You know,” my man says, “he looked like you.”

“The sexy one?”

“No,” he laughs. “The little one. Like you, but smaller, pocketsize. A mini-you.”

We drink, then head homeward, lighter. When I stumble, he reaches out to balance me, like Dorothy does for Scarecrow in “The Wiz.” I sing the number, Don’t you carry nothing that might be a load, but can’t get him to join in. The mirrored hotel is farther than remembered, or maybe we’re lost, but I’m following now, in silence. I’m trying to remember a line from a book, something triggered by an answer the little one had given to our questions. Then it comes to me, Hartley: The past is a foreign country … but I’m too blurred to remember the other half. I’m thinking about mini-me, how much he would have liked to caress the uncle, who was not really an uncle, the beautiful man in the Trix t-shirt, to kiss his neck, to slowly and carefully unclasp the chain, to slip off the crucifix, palm it, and ease away to the sound of laughter.

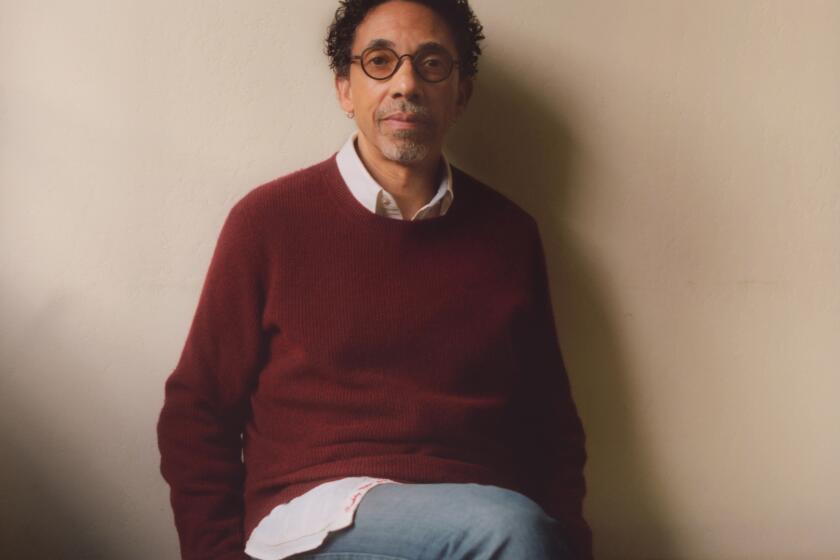

Justin Torres is author of the novel “We the Animals” and assistant professor of English at UCLA.