- Share via

We all know tiki bars and their dozens of classic fruity drinks have provided an escape for generations of Californians. But have you ever stopped to consider tiki bar food?

It has its own backstory. Pupu platters, coconut shrimp and other deep-fried delicacies once graced menus of tiki restaurants. But very few places still serve the crunchy and sticky bites that used to be standard alongside all the tangy tropical drinks.

At a recent happy hour at Trader Vic’s in Emeryville — one of the country’s original tiki bars — I finally had such appetizers: crab rangoon, chicken satay, spring rolls and “Chinese bbq” ribs. It got me thinking about where tiki food came from, where it went and how to re-create it at home, so you can control the quality of ingredients and hone — or start practicing — your deep-frying skills.

From classic tiki haunts to new speakeasies, these are the best tiki bars and Polynesian-inspired restaurants in San Diego, Orange County, Los Angeles and Ventura.

A couple months ago, some friends invited me out to Palm Springs smack dab in the middle of one of the hottest weeks on record. It felt like a hot hair dryer was directed squarely at our faces. We ventured into the Tonga Hut, a Palm Springs institution that still serves tiki food, as well as classic and new tiki cocktails, but we were too late to order the pupu platter, which comes with coconut shrimp, pot stickers and egg rolls. So we nursed our disappointment with drinks the color of white, blue or peach — one was served in a coconut with a shot of liquor flaming over the top — and decorated with paper umbrellas, pineapple wedges and bright red cherries. We played Jenga longer than any of us planned.

That’s the draw of tiki bars: No matter what state you find yourself in, by the time you sit down and sip a tiki drink, you’ll be in a much better mood.

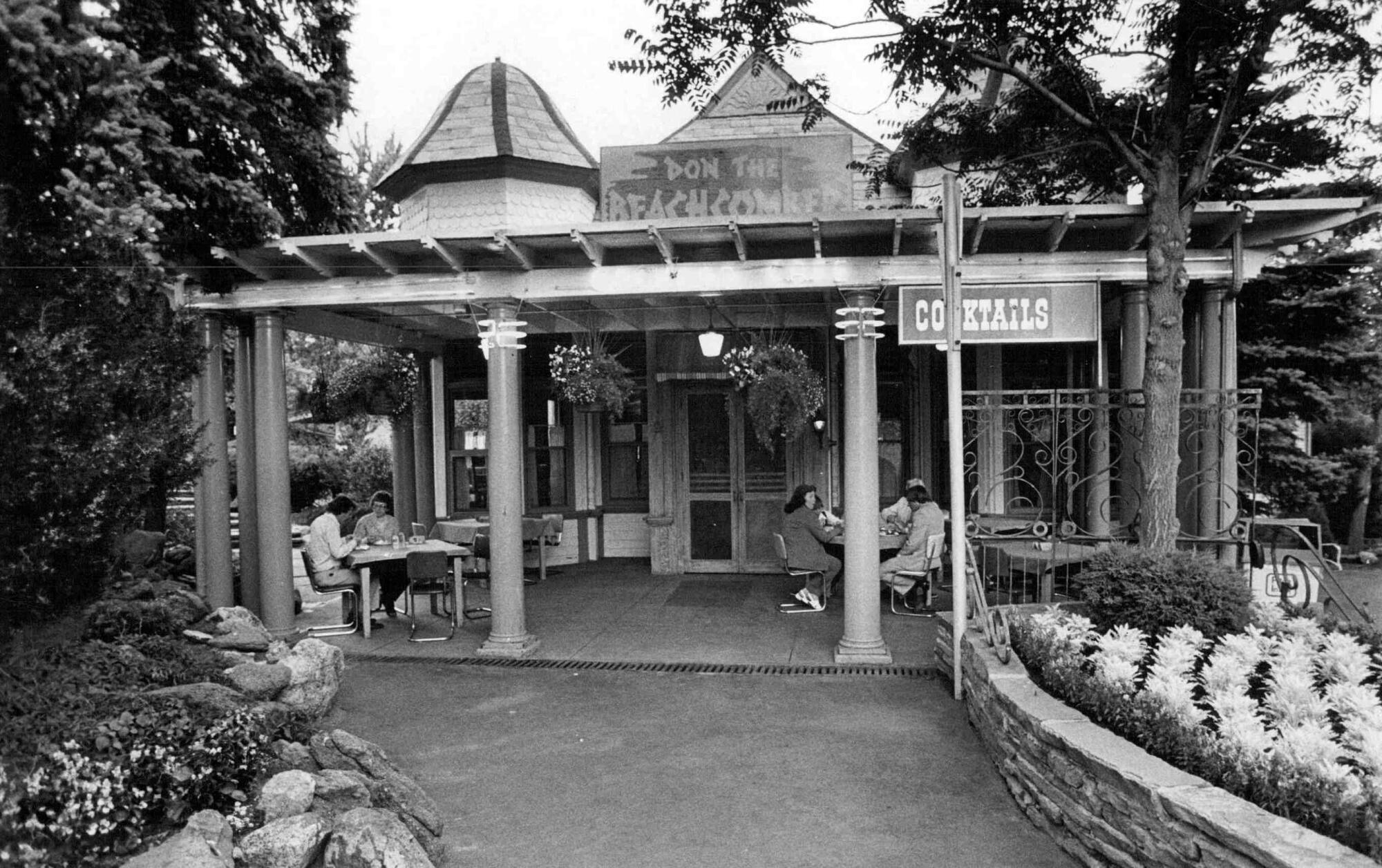

It’s one of my favorite pastimes since moving to L.A., the birthplace of the tiki bar/restaurant, where the original Don the Beachcomber (then called Don’s Beachcomber) opened in Hollywood in 1933. Tiki bars proliferated across Southern California, some of my favorites being the Tonga Hut in North Hollywood (which claims to be the oldest still operating in L.A. but does not serve food), Tiki Ti in Silver Lake and the Bamboo Club in Long Beach, which serves some Hawaiian and Southeast Asian-influenced food but not the original tiki standards.

In Tasting Notes, flaming tiki drinks

These bars still provide an escape for people when even the local dive or cocktail lounge can feel too much like the real life you need a break from.

And though I love these bars for their drinks alone, they haven’t aged well, politically speaking. Some consider the tiki bar phenomenon a racist reminder of our country’s fetishization of Asian cultures. Others see it as a crude dream world created by profiteers who exploited sacred iconography in order to sell the notion of paradise.

A case also has been made that tiki, like Disney, is an American pop invention — a pure fantasy that has stuck around and become a mainstay of Southern California culture.

The tiki boom took off after World War II with soldiers returning from the South Pacific, and Americans became fascinated with all things Hawaiian when in 1959 the islands became a U.S. state.

Tiki is a fantastical conglomeration of virtually every culture that exists in the tropics, pulling mostly from Polynesian cultures of the central and southern Pacific Ocean. Tiki bars boiled them down to totem poles, replicas of the Easter Island stone heads known as moai, volcanoes and coconuts that conveyed a mystical tropical paradise — while glossing over colonialism — to Americans newly able to drink post-Prohibition and looking for a respite from life during the Great Depression.

The tiki bar’s heyday came and went over the end of the 20th century. Yet tiki refuses to die.

What appealed to white patrons in the mid-20th century looking for entertaining distraction, mining Pacific Islander culture for a cheap thrill, now has a new audience of people of all backgrounds. For many, tiki bars are more vintage California than anything actually or ostensibly Pacific Islander in origin.

But while the decor and vibe of old-school tiki bars was a pure fantasy, the food that was once served in them was not. The food came from a real place with its own culinary legacy, and was then flowered up to go with the drinks served alongside it, until it barely resembled its source material.

Almond paste adds moisture and flavor to a dense cake that bakes atop a layer of fragrant cut pineapple, from a deli container for extra convenience.

But unlike tiki drinks, which have been updated with fresh juices, less sugar and more high-quality rums and booze, the food either stagnated or nearly vanished completely. Where menus used to be filled with pupu platters and coconut-crusted nibbles, now they list hamburgers, chicken tenders, fried calamari and other staples of sports bars and pubs.

But just as tiki drinks, and the culture, can be revisited, dissected and reassembled in a new way, so, too, can the food that used to be served with them.

When I first sought out answers to questions about the tiki food that everyone remembers, I immediately thought of Hawaii because the term “pupu” comes from native Hawaiian, meaning “small bites.” In his book “Cook Real Hawai’i” (Clarkson Potter, 2021), Sheldon Simeon states, “For [Hawaiian] locals, it implies a style of eating that is communal and never formal.” It is essentially what we’d call hors d’oeuvres or tapas or “small plates” today.

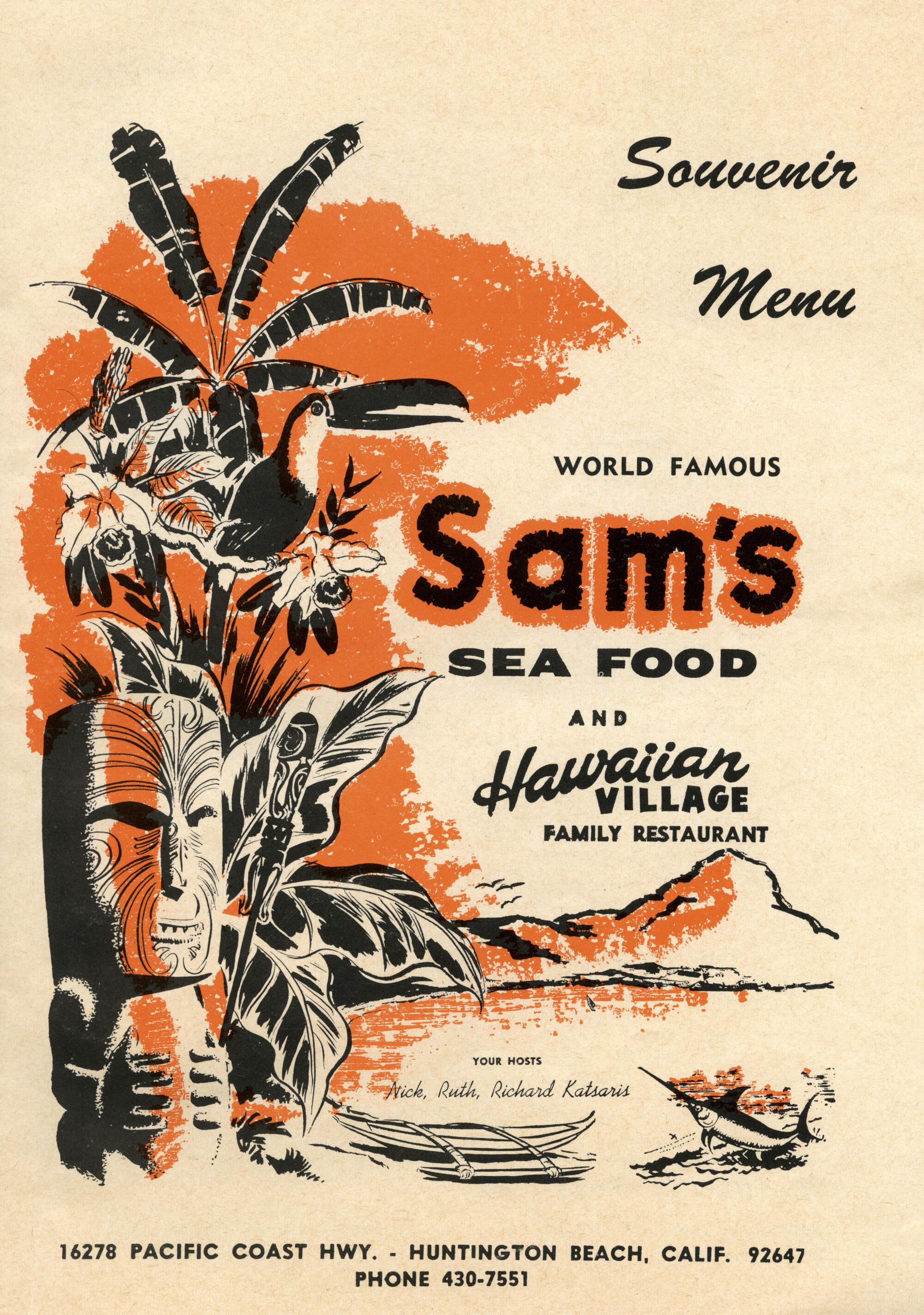

But tiki food is more Chinese than Hawaiian. In “Beachbum Berry’s Taboo Table: Tiki Cuisine From Polynesian Restaurants of Yore” (Club Tiki Press, 2013), Jeff Berry says Don the Beachcomber hired a Chinese cook who made the food he always did, and then Don rechristened it with Polynesian names to appeal to his audience.

Vic Bergeron — a.k.a. “Trader Vic,” who started his own chain of tiki restaurants in 1934 — served the food of Joe Young, his Chinese cook, with his tiki beverages.

Chinese chefs created what would become tiki cuisine, their original dishes subjected to various bastardizations and tweaks. Ironically, Chinese restaurants of the era, seeing the popularity of their food take off in Polynesian/tiki spots, adopted some tiki decor and drinks to cash in on the food they were already serving.

Tiki food became a mishmash of “international” and “fusion” dishes — a mix of Chinese, Asian Pacific and Hawaiian food to match with tropical cocktails — even though those drinks were made with Caribbean and Central and South American ingredients.

In “Trader Vic’s Pacific Island Cookbook” (Doubleday & Co., 1968), Bergeron opined that “certain Chinese tidbits seem to have an affinity for cocktails.” He served crab rangoon, barbecued pork and fried shrimp, as well as battered-and-fried oysters, egg rolls and rumaki, chicken livers paired with water chestnuts then bound with bacon. This type of deep-fried, heavily sauced food was standard fare with drinks in tiki bars.

The practice of serving them fell away, though you can still eat many of the classics at Trader Vic’s in Emeryville — the rich, crispy-crunchy, sweet-sauced appetizers to balance the tart-fruity tropical drinks. And with a resurgence of tiki bars has come new menus featuring some tiki dishes.

Make your own tiki party food

While I love experiencing these foods in their natural habitat, so to speak, I also want to re-create them at home, where I can exercise as much care in making them as I do for tiki drinks. It also allows me an opportunity to deep-fry, which, when done in small batches for a small group of people, is exceedingly more fun than you’d think and puts a smile on your guests’ faces.

For the crab rangoon, the original wonton-like dumplings — attributed to Bergeron, but likely also with collaboration from Young — used fresh crab and cream cheese, a novel ingredient of the time, flavored with A-1 Original steak sauce and, specifically, Lingham’s hot sauce, a Malaysian condiment that is spicier and less sweet than other Asian-style chile sauces.

Though crab rangoon served today often calls for imitation crab meat and sugar, I chose to stick with the original recipe, but flavored more boldly with the sauces than many recipes of the time suggest. I add sliced scallions to give the filling some lightness and freshness.

To balance the crunchy, cheesy rangoon, plum sauce usually is served alongside, but store-bought versions pale in comparison to homemade. It’s easier to make than you might think: Chop up some fresh plums and simmer them with sugar, vinegar and spices, and in about 15 minutes, you’ve got a bright and fruity condiment for the fried crab-and-cheese parcels.

Fried shrimp are another staple of the tiki appetizer platter, and though you might expect the typical coconut shrimp, they’re nowhere to be found on the Trader Vic’s menu. In fact, the fried shrimp served there today are coated in breadcrumbs.

A clue to how we ended up with coconut-coated shrimp likely lies in “Trader Vic’s Pacific Island Cookbook,” where one of the first recipes Bergeron includes is for “Coco Shrimp.” The name for the dish isn’t explained, but it details a wild process of frying dried rice noodles until crunchy, then breaking them up to coat the shrimp before frying again. I tried making them and immediately got the “coco” connection. Once the rice vermicelli noodles were fried, they became light and brittle and broke into many small, shredded-coconut-like strands.

Maybe the fried noodles were Bergeron’s, or Young’s, way of approximating the texture of shredded coconut that they couldn’t procure stateside? Though dried coconut has been used in American cooking since the mid-1800s, records are spotty about when sweetened shredded coconut, specifically, began being packaged and sold. Likely, it was post-World War II, so it’s feasible Bergeron and Young couldn’t find it — if they were looking for it — in Southern California in the late 1930s.

Or the name “coco” was a mistranslation of another word that sounded fun and whimsical to Bergeron, and then over time “coco” was thought to mean “coconut”? And that’s how we ended up with coconut shrimp today?

My bet is on the latter.

In any case, the original recipe called for coating peeled and deveined shrimp in beaten egg and then a mixture of the crushed, fried rice noodles combined with flour, salt and pepper and MSG. I found that a double coating of both egg and the noodle mixture created a sufficiently crunchy coating for the shrimp. You can serve them with a sweet chile sauce as they do at Trader Vic’s, but I prefer Bergeron’s suggestion: cocktail sauce mixed with prepared horseradish.

The last of the trifecta of tiki hors d’oeuvres is sticky-sweet, pineapple-flavored pork. Both ribs and pork tenderloin are found in tiki recipe books. To avoid having to deal with the time-consuming process of cooking ribs, I opt for tenderloin, which has the added benefit of acting as either appetizer or as a main course if you decide to compose a full meal for your tiki party.

Roasting pork tenderloin takes only a dozen or so minutes at high temperature, which is just long enough to bring together a bubbling and fragrant barbecue-like sauce to glaze and serve it with. I make a sauce based on ketchup that’s cut with pineapple juice, rum, soy sauce and hot sauce.

Brush the sauce on the pork tenderloin in the last few minutes of roasting. The rest is served as a dipping sauce on the side. You can cut the meat into thin slices for appetizers or thicker slices to serve with rice and steamed greens for dinner.

While the pork is roasting, you can drop a few of the crab rangoon packets in a small pot of bubbling oil, followed by the crunchy shrimp. I’ve developed both fried recipes to use one quart of vegetable oil, which easily fits into a medium saucepan that’s ideal for frying half a dozen of each item at a time. Working with this level of oil keeps things smaller and easier to handle, which is why deep-frying can be so fun for small — maximum six people — dinner parties.

Once the pork is done and sliced, the hot-from-the-fryer rangoon dumplings and crispy shrimp can make their way onto a serving platter with their sauces, and you can set out the spread for your guests.

It’s an approachable but fun route to tiki food that maintains the appeal of its whimsical and oddball nature but makes it tasty too. At the very least, it provides a night of tropical escapism for your friends and provides plenty of fodder for lively dinner conversation.

Get the recipes:

Rice Noodle-Crusted 'Coco' Fried Shrimp

Crab Rangoon with Plum Sauce

Sweet-and-Sour Pork Tenderloin

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.