- Share via

Climate change is transforming the character of the West’s hottest periods — making them more frequent, more persistent and more lethal.

For almost all of human history, heat waves have been driven by natural variability — or the tendency of weather patterns to veer occasionally from their typical patterns. Now, however, the accumulation of greenhouse gases due to the burning of fossil fuels is increasing the likelihood and severity of such extreme heat events.

Although California and the American West will continue to experience cool days and periods of heavy snowpack, scientists say the long-term trend is for the planet to grow hotter with the continued burning of fossil fuels. Since 1880, the global average temperature has increased by about 2 degrees.

How is climate change affecting the length and duration of heat waves? How will rising temperatures affect people and ecosystems? How much hotter is it expected to be if current emissions continue unabated?

A powerful high-pressure ridge will bring unusually hot temperatures to the Golden State by the middle of this week, before spreading into the Pacific Northwest.

Here’s what the experts say:

How do we know that the planet is warming?

The temperature readings in Earth’s atmosphere and its oceans are monitored by thousands of weather stations, buoys and ships around the world. Scientists use this data to calculate a global average temperature.

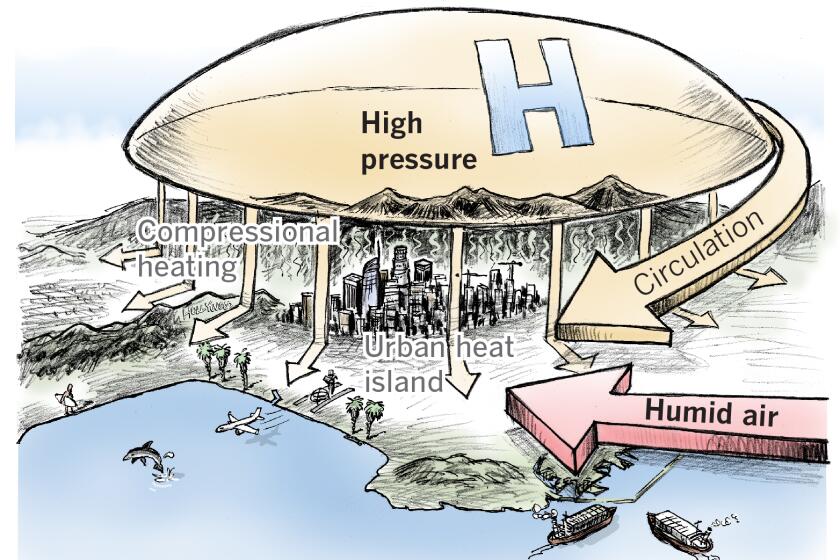

California’s worst heat waves arrive in a one-two punch — high temperatures combined with humid air from Baja.

“We know that the planet is warming because all these groups are independently documenting a clear, long-term increase in our global average temperature,” said Kristina Dahl, principal climate scientist with the Union of Concerned Scientists, a national nonprofit organization.

“It’s a trend that can’t be explained by any natural causes, such as changes in volcanic eruptions or solar radiation,” she said. “Human emissions of carbon dioxide and methane, two known, potent heat-trapping gases, very clearly explain the trend we’ve seen.”

Nineteen of the 20 hottest years on record have occurred since 2000, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The year 2023 was the planet’s warmest on record so far. In July, Phoenix recorded 31 consecutive days of temperatures of 110 degrees or higher — the hottest month on record for any U.S. city.

In 2021, an anomalous and extreme heat wave in the Pacific Northwest killed hundreds of people and an estimated 1 billion sea creatures off the coast of British Columbia. A study of that event found that such heat waves could become 20 times more likely if current carbon emissions continue.

Read all of our coverage about how California is neglecting the climate threat posed by extreme heat.

How much hotter is it expected to be if current emissions continue unabated?

Scientists use a range of potential future emissions scenarios to try to discern how emissions choices will affect all aspects of our climate, Dahl said. Here’s a sampling of what those scenarios show:

- If emissions continue at current levels until about 2050, then start falling thereafter, global temperatures would warm by nearly 5 degrees by the end of the century. This is what the Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change considers a “middle-of-the-road scenario.”

- With the current policies in place, we’d experience a similar amount of warming — in the range of 4.3 to 5 degrees — unless those policies are strengthened significantly. California aims to achieve carbon-neutrality by 2045, while the nation as a whole is aiming for 2050. Other countries have longer targets, such as China, which is aiming for 2060.

- In a worst-case scenario, in which our heat-trapping emissions triple by about 2075, the planet would experience about 8 degrees of warming. This is unlikely, as it implies higher emissions than the path we’re on.

How is climate change affecting the length and duration of heat waves?

For much of the U.S., extreme heat events have been increasing in frequency since the mid-1960s, and the number of high temperature records has been outpacing the number of low temperature records since the mid-1980s.

“While there’s no one definition of what constitutes a ‘heat wave,’ we know that cities throughout the U.S. and around the world have been experiencing more intense and longer-lasting heat waves over the last 60 years,” Dahl said. “If we look globally, the number of days with heatwaves has nearly doubled since the 1980s. During that time, heat waves have also increased in duration.”

Extreme heat waves such as the one that hit the Pacific Northwest last year may be 20 times more likely to occur if carbon emissions are not reduced.

What are the potential consequences of rising temperatures for people and ecosystems?

Extreme heat is one of the deadliest effects of climate change. Each year, extreme heat kills more Americans than any other climate-fueled hazard, including hurricanes, floods and wildfires, but it gets far less attention because it kills so quietly.

A 2021 Times investigation found that California has chronically undercounted the death toll from extreme heat, which disproportionately harms poor people, elderly people and others who are vulnerable.

High temperatures can affect the human body in many ways. Heat can cause dehydration, dizziness and headaches, and can worsen underlying health problems such as cardiovascular disease. Health trackers typically show spikes in deaths related to heart problems during and in the days immediately following heat waves.

A blistering California heat wave in September 2022 killed 395 people, according to state health officials.

California chronically undercounts the death toll from extreme heat, which disproportionately harms the poor, the elderly and others who are vulnerable.

During Phoenix’s record heat in the summer of 2023, emergency rooms also saw increases in people suffering from pavement burns, as concrete can reach 170 degrees or hotter amid high air temperatures. Officials said many burn patients may have passed out on the pavement due to dehydration, intoxication or other factors that lengthened their exposure and complicated their treatment.

People who work outdoors or otherwise lack air conditioning are particularly at risk of heat-related illness and death during an extreme heat event. California has established heat standards for outdoor workers, but has not yet done the same for indoor workers.

Aside from the health risks, “more frequent, more severe extreme heat also shapes the way we live and experience the world around us, from whether we can enjoy a visit to a national park to whether it’s safe to walk a few blocks to get an ice cream cone,” Dahl said.

That includes effects on ecosystems.

For example, warming temperatures have enabled pests such as bark beetles to survive through the winter and expand their range, which has decimated Western forests. Avery Hill, a postdoctoral researcher at the California Academy of Sciences, noted that for every 1.8 degrees of additional global warming, up to 40% more trees could die from beetle infestations.

Warming temperatures are also implicated in drying out vegetation, which can contribute to larger, faster and more frequent wildfires.

What’s more, forests that don’t recover from severe fires can shift into different ecosystems entirely, which not only affects the range of plants and animals in the area, but can also affect the larger food web, Dahl said.

Global surface temperatures last month were 2.25 degrees above the 20th century average of 60.1 degrees, surpassing the record set in August 2016.

It’s been warm before. Isn’t the planet always changing?

Earth’s climate has always changed and it will continue to change as a result of things like changes in the shape of our orbit around the sun, Dahl said. However, the changes documented over the last 150 years or so are unprecedented.

There is now more carbon dioxide in our atmosphere than at any point in the last 2 million years, she said. Sea levels have risen more quickly over the last century than in any prior century for the last 3,000 years. Glaciers — and the critical freshwater they contain — are retreating at a faster pace than during any period in over 2,000 years.

“The source of these changes is very clear: It is us. We are changing our climate because of our thirst for fossil fuels and the energy they provide,” Dahl said.

From a geological perspective, one could argue that because humans are part of the planet, these changes are natural, or that we shouldn’t do anything to fix our changing climate.

“But the reality is that humans have never lived through this kind of change before,” Dahl said, “and if we want to alleviate the suffering of people, plants and animals that are experiencing this change most acutely, we will have to wean ourselves off of fossil fuels, and sooner rather than later.”