What put Hurricane Hilary on a collision course with California?

- Share via

For as long as meteorologists can recall, California has been protected from the wrath of hurricanes by three robust natural defenders:

The first is a frigid ocean current that flows down the Pacific Coast, robbing storms of their strength-building tropical heat.

The second is a prevailing east-to-west wind pattern that serves to shoo angry storms out to sea before they can collide with the mainland.

And the third is atmospheric subsidence — a downward flow of air over California that squishes storms before they can form, and also contributes to the state’s moody marine layer.

For at least the last 165 years, these conditions have kept California hurricane-free, experts say.

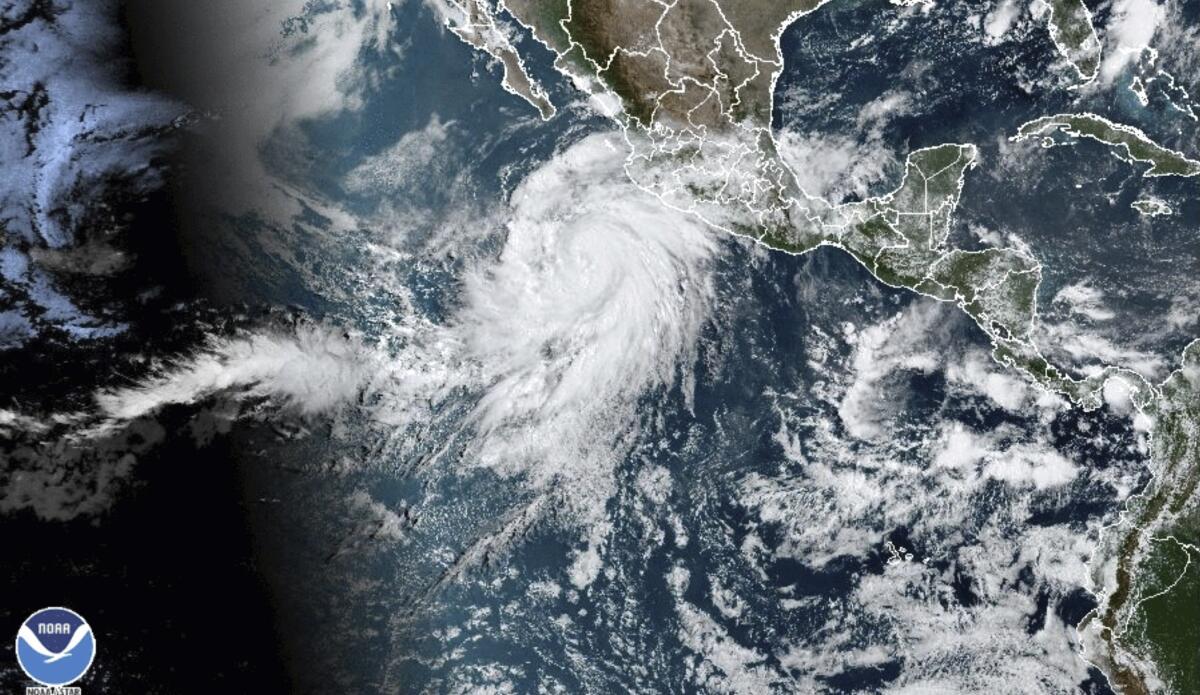

This year, however, an unusual set of weather patterns and warm Pacific Ocean waters have short-circuited these normally reliable safeguards and allowed Hurricane Hilary to make its hell-for-leather dash for Southern California.

Although meteorologists predict that Hilary will weaken to a tropical storm by the time it arrives, the circumstances that have allowed it to get this far are exceedingly rare.

The extraordinary situation has prompted the National Hurricane Center to issue its first-ever tropical storm watch for the region this weekend, while the National Weather Service has announced flood watch advisories from Santa Barbara to Flagstaff, Ariz.

In the Southland, a region where any measurable rain in August is a rarity, some areas could be inundated by a year’s worth of precipitation in a matter of days, especially in the inland valleys and deserts.

“It’s probably going to take some people by surprise, because most people don’t even bother to check the weather in August in Southern California,” said Daniel Swain, a UCLA climate scientist. “So the impacts could be elevated, because this is coming so much out of left field relative to the typical August conditions, and that may reduce people’s level of vigilance.”

California is familiar with natural disasters. The state witnesses more than 4,000 wildfires and about three major earthquakes a year, and major flooding and mudslides each winter. But the possible arrival of a hurricane or tropical storm in California is yet another marker of how unprecedented climate conditions have reshaped what residents can expect, in an astonishingly short period of time.

Wildfires in Canada and Hawaii. Hurricane Hilary set to strike California. Scientists have warned about worse storms and more frequent fires for years.

In the southeastern U.S., several hurricanes form each year in the warm waters of the Atlantic, where currents move tepid water from south to north. On the West Coast, ocean currents carry water from north to south, bringing colder water from Alaska to California, which typically acts as a deterrent to tropical storms.

“Very warm ocean water is essentially hurricane fuel,” Swain said. “So you generally need water temperatures getting up toward around 80 degrees or warmer on a sustained basis. The all-time record, high temperature at Scripps Pier [in San Diego] is right at 80 degrees, so we’re almost always well below this temperature threshold the ocean would be required to generate or sustain a tropical cyclone.”

But globally, July set a record for the highest monthly ocean surface temperature in NOAA’s 174-year history. And specifically, ocean temperatures off the coast of Baja California are higher than normal, due to the warming effects of El Niño and the proliferation of fossil fuel emissions.

“Over the last 40 years, climate change has made hurricanes more powerful, both in terms of wind speed and the amount of water they deliver as rain,” said Kristy Dahl, principal climate scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists, a nonprofit advocacy group based in Massachusetts. “To see a storm of this magnitude in this part of the world — and at this time of year — is highly unusual.”

Hurricane Hilary is likely to make landfall in Los Angeles as a tropical storm, bringing heavy rains and potential flooding. Here’s what you can do now to prepare, and how to stay safe when the storm arrives.

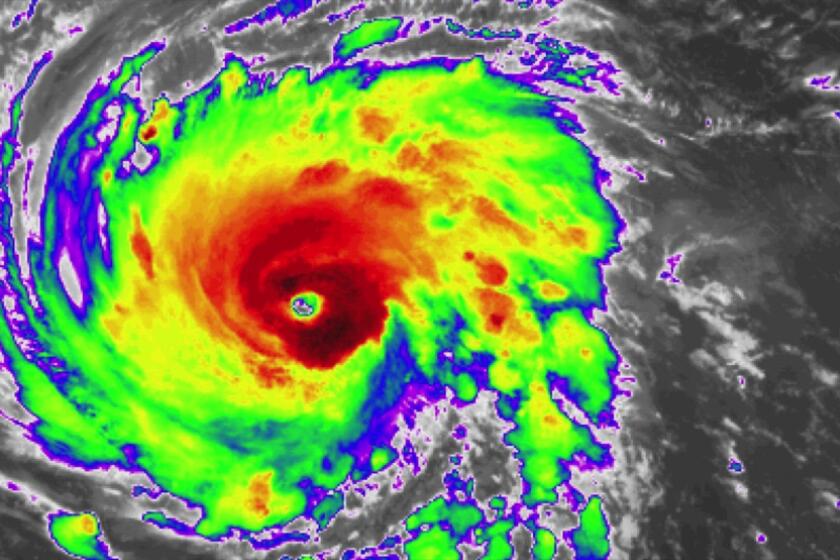

By Friday afternoon, energy from these steamy waters had boosted Hilary to a Category 4 hurricane with 145-mph winds, but it weakened Saturday to a Category 3 hurricane with winds under 130 mph. Though experts had anticipated the storm would lose strength as it encountered colder waters closer to California, they do not expect it to diminish into a tropical depression or fragmented storm cells as it typically would.

“It simply isn’t going to have time to completely fall apart before it gets here,” Swain said.

But warmer waters are not the only factor. Some of the strongest hurricanes on record have formed in the Pacific, including Hurricane Patricia, a Category 5 storm that rocked southwestern Mexico in October 2015.

Typically, these storms are blown away from California, shunted out to sea by prevailing easterly winds. But that is not the case with Hilary. Due to a pair of unique atmospheric conditions, those east-to-west winds have vanished.

These conditions include a very unusual ridge of high pressure building over the central United States — a weather pattern that could bring extreme heat to that area. The other factor is an unusually persistent trough of low pressure off the West Coast. In between these two regions, winds are now blowing from south to north, experts say.

“That is helping to direct this tropical system right up into Southern California,” said Jayme Laber, a hydrologist with the National Weather Service in Oxnard.

The consequences for Southern California are serious. The average rainfall in the month of August is less than 1/10 inch, and Hilary is expected to bring 2 to 4 inches to much of the region. Even higher precipitation is forecast for the San Gabriel and San Bernardino mountains.

In Los Angeles, the Department of Water and Power said its reservoirs have the capacity to handle floodwaters, but noted that crews were still monitoring them. Workers were also clearing vegetation and other potential blockages near storm drains in preparation for the deluge.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has also activated its Reservoir Operations Center and will be monitoring water levels and flows throughout the weekend, said Dena O’Dell, public affairs chief for the corps’ Los Angeles district.

The Army Corps is also working with law enforcement agencies and advocates for unhoused people to help move them out of basins and river areas that are used to help with flood risk management.

“This is not a time for people to be in those areas,” O’Dell said. “It becomes a life safety issue, especially because this is so rare for SoCal. It is not a time to be recreating in these areas, not a time to be living in these areas. We’re not trying to panic people, but we do want to make sure that they’re safe.”

Also Friday, workers were building sand berms on many Los Angeles-area beaches in hopes of creating a bulwark against increasing waves. Long Beach officials distributed sandbags at fire stations and a lifeguard post as the city prepared for storm surges that typically only occur in the winter.

Hurricane Hilary is a reminder to sign up for services that alert you when storms, extreme heat, earthquakes, tsunamis or fires threaten or hit an area.

Perhaps one of the few benefits of Hilary’s visit will be its effect on the threat of wildfires.

The moisture is expected to diminish Southern California’s fire risk for several weeks — effectively ending the traditional summer fire season, according to Jonathan O’Brien, a meteorologist with the National Interagency Fire Center’s Predictive Services in Riverside.

Worldwide, climate scientists say the strongest storms are becoming more intense as the atmosphere warms. A warmer world may have stronger hurricanes, though there’s still debate about how it might influence the frequency of tropical cyclones.

“Broadly speaking, as the climate warms, sea surface and ocean temperatures generally tend to get warmer, and that adds more fuel to intensify tropical cyclones,” said Jane Baldwin, assistant professor of earth sciences at UC Irvine. “So having Hurricane Hilary, as a relatively intense storm, develop is consistent with the fact that we expect more intense tropical cyclones to be more likely with climate change.”

Before this week, Baldwin, who came to California from New York’s Columbia University two years ago, thought her days of exploring hurricanes were behind her after she left the East Coast. But she now expects this to jump-start new research on tropical storms in the West.

“It’s certainly unusual for any tropical storm to take the path that Hilary has — much less one that’s this intense,” Baldwin said.

The last tropical storm to make landfall in the region occurred in September 1939 in Long Beach, when an unnamed storm brought 65-mph wind gusts and drenched the region in more than 5 inches of rain over three days. Ninety-three people died in flooding and at sea, while the storm caused around $2 million in damage to shoreline structures, power lines and crops.

The only tropical cyclone packing hurricane-force winds to make landfall in California is believed to have hit San Diego in October 1858 — an event meteorologists learned about through newspaper archives and historical anecdotes.

“I think what it really highlights is that it’s not physically impossible,” said Swain. “But it is very rare for a full-fledged tropical storm or hurricane to actually make landfall in Southern California.”