- Share via

HOLTVILLE, Calif. — Just north of the California-Mexico border, the All-American Canal cuts across 80 miles of barren, dune-swept desert. Up to 200 feet wide and 20 feet deep, the canal delivers the single largest share of Colorado River water to the fertile farmlands of the Imperial Valley.

It’s more water than what Los Angeles, Phoenix and Las Vegas get combined, and it’s used to grow lettuce, broccoli, carrots and spinach, as well as hay to supply beef and dairy operations, wheat, melons, lemons and other crops.

Since its founding in 1911, the Imperial Irrigation District has held some of the most senior water rights on the river, and it is among the last in line to take cuts. Its water rights, which date to 1901, support the local farm economy and sustain a substantial portion of the nation’s food supply.

But as the Colorado’s largest reservoir declines closer to “dead pool” levels, politicians and water managers in other states are calling on the IID to make cuts beyond the 250,000 acre-feet, or about 9%, that the agency has pledged to make starting this year. They say that the dire state of Lake Mead warrants larger cuts, and that much of the reductions will need to come from agriculture because roughly 80% of the river’s water is used for farming — a large portion of it for alfalfa and other thirsty crops.

The demands have struck an anxious chord among Imperial Valley growers, who say their way of life could be threatened and the country’s food security is at stake. There are about 400 farms in the Imperial Valley, and together with nearby farmlands around Yuma, Ariz., they produce most of the country’s winter vegetables.

Farmers say they understand the crisis is serious and that everyone needs to use less water from the river. But many are adamant that they hope to avoid leaving fields dry and fallow, which they say would harm the economy and food production. They say they are willing to shift to more water-efficient irrigation systems to free up water and boost reservoir levels, so long as they are paid enough to help foot the bill.

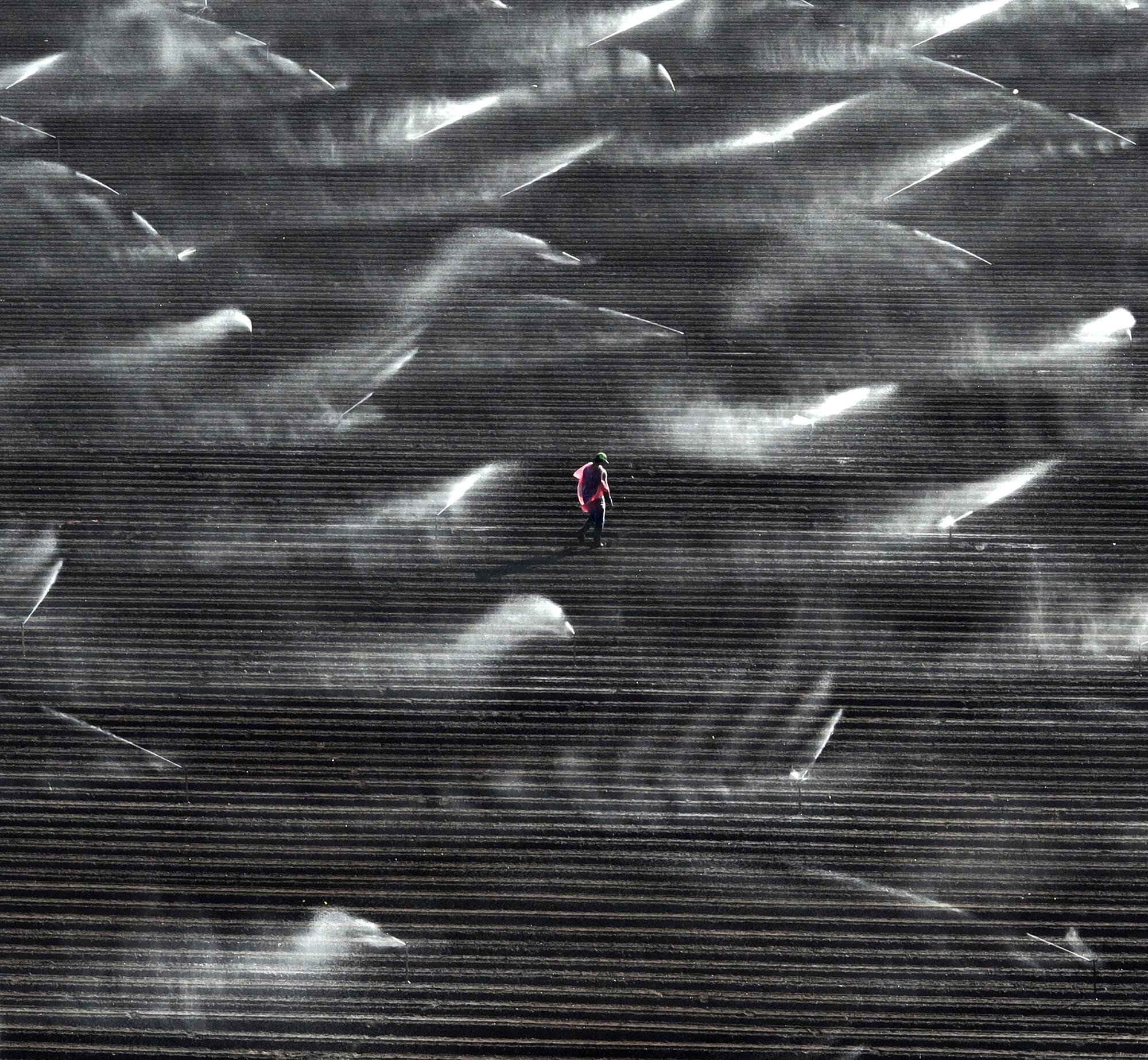

Some growers have already been installing water-saving sprinklers on their fields, aiming to stretch the available water further and prepare for drier times.

“The Colorado River system is in dire straits,” said Ben Abatti III, a 28-year-old farmer. “We know we’re going to have to save water.”

Beside him, sprinklers sprayed a field of newly planted basil, the spray glowing in the sun. The sprinklers use less water than the usual practice of opening canal gates and letting the water flow in to flood fields.

Abatti estimates that assembling the network of pipes on a field can reduce a row crop’s water consumption by 10% to 25%. The sprinklers can also help boost crop yields. But they are expensive, he said, costing about $4,000 per acre to buy or about $400 per acre to rent for a season.

Colorado River in Crisis is a series of stories, videos and podcasts in which Los Angeles Times journalists travel throughout the river’s watershed, from the headwaters in the Rocky Mountains to the river’s dry delta in Mexico.

Installing more sprinklers and other water-efficient irrigation systems would enable the valley’s farmers to significantly reduce water usage while maintaining crop production, Abatti said. He said he hopes farmers will receive financial help so they can scale up conservation while continuing to farm.

The Bureau of Reclamation is offering $4 billion in drought mitigation funding, including money to pay growers who temporarily forgo some of their water.

Farmers and IID officials have said they prefer to prioritize improving water efficiency rather than leaving farmland dry. The district could conserve by lining more of its earthen canals with concrete to keep water from seeping into the ground, and by building other infrastructure to reduce spillage.

But some of the district’s board members have acknowledged that some land-fallowing will probably be necessary, at least temporarily.

“We don’t want to take land out of production,” Abatti said. “Here in the Imperial Valley, fallowing would be an absolute last resort.”

He and his family, who rent much of their land, are growing hay, sugar beets, cilantro, parsley, basil and wheat.

Abatti is a third-generation farmer who works with his father, mother and brother. He started driving a tractor with his father when he was 8.

“It’s kind of just in my blood,” he said. “And I’d love to keep doing this.”

But he and other farmers say they’re increasingly concerned about the risks of a worst-case scenario. And some criticize the federal government for not imposing larger cuts throughout the region sooner to head off a potential disaster.

If Lake Mead were to hit “dead pool” levels, that would cut off the flow to California, Nevada and Mexico, including the only supply of water for nine cities and about 500,000 acres of farmland in the Imperial Valley. In such a scenario, Abatti said, farm fields would turn to dust, people would be forced to move, and Americans would see food shortages and higher prices at grocery stores.

“There’s already a rent crisis, a housing crisis. You know, wait till the food crisis,” Abatti said.

Drought and global warming have transformed the Colorado River, making some sections unrecognizable to those who have spent decades on the river.

He and other growers say they see an urgent need to reduce water use throughout the Southwest, and they’re bracing for larger cuts.

Andrew Leimgruber, a fourth-generation farmer, said he is disappointed with how federal officials have handled the situation as the reservoirs have dropped.

“Unfortunately, I believe mismanagement led us to this point,” Leimgruber said.

“Because they’ve continued to kick the can down the road, now we’re getting to crisis levels. I think it would have been much easier to manage and mitigate the problem earlier on,” Leimgruber said. “We should have been making cuts quicker. I believe we need to be making more cuts than we are now. And it’s going to cause pain.”

As he spoke, workers were laying out the metal pieces of an overhead sprinkler system to irrigate a field of organic greens. The scent of freshly tilled soil filled the air.

“I believe that the burden is going to have to ultimately be shared by all and that some major changes need to happen,” Leimgruber said. “But it can’t just always be off the backs of agriculture.”

Leimgruber said he is putting in four new water-saving irrigation systems. He and other growers can still do more to conserve, he said, “but a lot of us think anything over 20% in reduction would have huge impacts.”

Over the last two decades, the Imperial Irrigation District has significantly scaled back water use. Under a 2003 water transfer deal, the district began selling water to Southern California cities, reducing its annual usage from 3.1 million acre-feet to about 2.6 million acre-feet.

Those savings have been achieved partly through a program in which growers propose plans for conserving on their farms and receive payments from the district. In the deal’s initial years, the district also paid farmers to leave some fields dry, but land-fallowing was controversial and was phased out.

Some landowners have converted thousands of acres of farmlands to solar panels, allowing the water to be used elsewhere.

But farmers say they don’t want to fallow much land because they’ve seen how drying up fields affects the whole farm economy, from laborers to sellers of seeds and supplies.

Stephen Benson, a farmer and former IID board member, said the question should be how to redouble conservation efforts while keeping farms going.

“We have implemented drip. We’ve implemented sprinklers on crops that have never used those systems. And the reality is we can conserve water, but the cost is so high,” Benson said. “There needs to be a set of incentives.”

Some researchers have suggested that because alfalfa and other cattle-feed crops consume a large share of the river, an effective way of dramatically reducing water use would be to leave some of these lands dry on a rotating basis or seasonally.

In the last year, though, alfalfa prices reached record highs. And some farmers say it makes sense to keep growing hay because it’s lucrative.

Another major issue is the shrinking Salton Sea, which is fed by agricultural runoff. The water transfer deal has accelerated the lake’s decline. Its ecosystem has been deteriorating, and its retreating shorelines spew dust into communities where people already suffer from asthma at high rates.

The Imperial Irrigation District’s managers demanded federal money to support environmental projects at the lake as a key condition for participating in cuts. And the Biden administration responded with a plan to provide $250 million to accelerate the construction of wetlands along the retreating shores to provide habitat for birds and help control dust.

California uses more Colorado River water than any other state. And some officials from other states have been pushing for California’s big water users, including the IID, to agree to larger reductions.

In contrast to the Imperial Valley’s senior water rights, Arizona’s cities rely on junior rights that are vulnerable to cuts. This year, Arizona is already being forced to take 21% less water from the river.

Tom Buschatzke, director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources, has said the water-rights priority system is the “single biggest thing that is making discussions among the states extremely difficult.”

“Higher-priority water users are saying it should be the lower-priority water users that should do this,” Buschatzke said. “But at the end of the day, if the system crashes, and no water’s coming out of either lake, your priority and your piece of paper doesn’t mean a thing.”

The priority system, he said, is “creating an outcome in which it’s much harder to collaboratively find a path forward.”

Former Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt and others have suggested it’s time to revamp the 1922 Colorado River Compact, which divided the water among the seven states, to include measures for apportioning reductions.

Water managers from Nevada and other states have urged the federal government to start accounting for evaporation losses from reservoirs and canals in the river’s Lower Basin, which could translate into major reductions for California.

Some farmers in Imperial County say that they’re willing to help reduce water use but that the system for dealing with shortages is laid out in the law of the river. They point out that the water-rights system requires those with junior water rights, such as Arizona’s cities, to take the largest cuts first.

“The rules are the rules,” said John Hawk, a farmer and Imperial County supervisor who lives in Holtville. “Follow the rules and let’s all make cuts. And it’ll be heavier cuts in Arizona than it will be here in California.”

Hawk grows lettuce, onions, parsley, wheat and hay. His father worked on the construction of the All-American Canal in the 1930s, using a mule team to pull a grader.

Hawk said he would be willing to cut water use by giving up a wheat crop and temporarily fallowing some land — if he receives compensation.

“We want to do our part,” Hawk said. “All of us need to learn to live with less. And, you know, the West is arid. I mean, this is liquid gold.”

The Colorado River is approaching a breaking point, its over-tapped reservoirs dropping. Years of drying have taken a toll at the river’s source in the Rockies.

Some farmers say they fear that powerful city water agencies could try to target the Imperial Valley’s water as the shortage worsens.

“We do not know what’s going to happen with the water,” said Luis Velez, a 21-year-old farmer.

Velez, who started his company at 19, has been growing alfalfa, Bermuda grass, wheat and onions. But during part of last year, the shortage prompted the IID to impose a water limit on each farm under its so-called equitable distribution plan.

To stay under his allocation, Velez decided not to plant one 30-acre field of onions.

“This is a very high-producing field,” Velez said, standing on the bare, hardened dirt. “I decided not to plant anything this year, because just of the uncertainty that growers are experiencing. I do not know if I’m going to be able to finish out this crop, if we’ll have enough water.”

Velez said he’s also dealing with rising costs for fertilizer, fuel and other supplies. And he feels uncertain about the future.

“Honestly, I’m scared,” Velez said. “I don’t know if I’ll be here in the next 10 years farming, just due to the water issues.”

Velez said he hopes to continue farming.

“We love doing what we do,” he said. “But we feel threatened.”