Climate change is looming. But America has lost 600,000 clean energy jobs

- Share via

The United States shed more than half a million clean energy jobs in March and April, a new report says, reversing years of growth in an industry that has helped reduce lung-damaging air pollution and the emissions responsible for climate change.

Clean energy employment has fallen by 17% since the coronavirus brought much of daily life to a screeching halt, according to unemployment data analyzed by BW Research and published Wednesday by advocacy group Environmental Entrepreneurs. The numbers are especially grim in California, where 105,000 clean energy workers have lost their jobs, more than any other state.

Los Angeles County lost nearly 15,000 clean energy jobs in April alone, 2 ½ times as many as any other U.S. county.

“These are higher numbers than expected, and we were expecting bad numbers,” said Greg Wetstone, president of the American Council on Renewable Energy, a trade group. “It’s painful to see three years of growth essentially wiped out in a single month.”

The 594,300 nationwide unemployment claims span a wide range of job types, including rooftop solar installers, wind turbine technicians and factory workers who build electric vehicles, Energy Star appliances and high-efficiency air conditioning systems.

Around 70% of the newly unemployed people worked in energy-efficiency jobs, which have been hit particularly hard because the installation of new lighting and appliances often involves workers going into homes — a scary prospect during a pandemic.

Environmental factors including deforestation, air pollution and urbanization contribute to the severity of pandemics like COVID-19. Experts warn that if we continue to destroy the environment, future pandemics could become more common.

Your guide to our clean energy future

Get our Boiling Point newsletter for the latest on the power sector, water wars and more — and what they mean for California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Despite the sudden nosedive, advocates say the clean energy sector can play a key role in economic recovery efforts.

Before the arrival of COVID-19, nearly 3.4 million Americans worked in clean energy — three times the workforce of the U.S. fossil fuel industry, according to Environmental Entrepreneurs. The Bureau of Labor Statistics projected last year that the country’s two fastest growing jobs over the next decade would be solar panel installer and wind turbine technician.

“The pieces remain in place,” Wetstone said. “Our product, wind and solar power, is very cost-effective.”

The federal government has offered little support for renewable energy thus far. In a tweet last month, President Trump said that his administration would “never let the great U.S. Oil & Gas Industry down” and that he had instructed top officials “to formulate a plan which will make funds available so that these very important companies and jobs will be secured long into the future!”

Trump’s approach to recovery ignores the climate crisis, which is driven largely by the burning of coal, oil and natural gas, and which is already contributing to worsening wildfires, droughts, floods and sea level rise in California and across the country.

Outside the White House, the pandemic has unleashed a torrent of proposals for how policymakers might use public dollars to boost employment in the clean energy sector and ensure the transition away from planet-warming fossil fuels is not derailed.

The Washington-based International Monetary Fund released a paper last month calling on national governments to “support green, rather than brown, activities” as they craft recovery plans and to make any support for fossil fuel companies “conditional on making progress on climate.” The IMF stressed that climate crises “may look remote but can strike quickly,” just like the pandemic; that preparedness takes years; and that “the cost of preparing is dwarfed by the cost of not preparing.”

“What we do now will not only reshape our economies and societies, it will also reshape humanity’s future on this planet,” IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva said last month. “Coming out of one crisis need not be a prelude to getting into another.”

Welcome to the first edition of Boiling Point, a newsletter about climate change, energy and the environment in the American West.

In California, policymakers are taking that idea to heart.

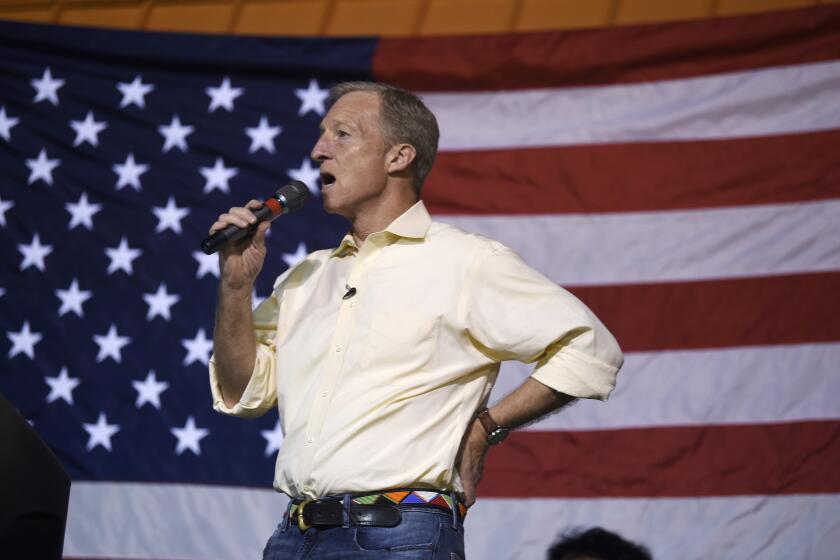

Gov. Gavin Newsom appointed Tom Steyer, a billionaire former hedge fund manager turned climate change activist, to co-chair his Task Force on Business and Jobs Recovery. Twenty state lawmakers signed a letter last month to Steyer and Newsom’s chief of staff, Ann O’Leary, urging the governor’s office to consider recovery investments that prioritize “clean economy job creation.”

“We know the clean economy — transportation, housing, energy, water, manufacturing, waste, and natural and working lands — is one of the most cost-effective, resilient job creation sectors economy-wide,” the letter reads.

State Sen. Henry Stern (D-Canoga Park), who wrote the letter, is helping develop a detailed proposal for what those investments might look like. In an interview, he listed several areas that could be targeted, including renewable energy facilities such as solar and wind farms, infrastructure to support electric vehicles and water recycling projects to drought-proof Southern California.

“There’s a number of sectors that are hurting right now that we think could give a good return on investment,” Stern said.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Subscribe to the Los Angeles Times.

Gov. Gavin Newsom tapped Steyer to help craft California’e economic response to the COVID-19 pandemic. He discusses some of his task force’s goals.

He also said it’s important not to draw too much on California’s general fund, because the state faces an estimated $54-billion budget deficit. Other options for policymakers include borrowing money or speeding up the distribution of previously allocated dollars.

Stern is already the coauthor of a $5.5-billion bond measure focused on wildfire prevention, safe drinking water and hardening the coastline against sea level rise. He also suggested lawmakers could require utility companies to purchase more renewable energy than is already required under state law, thus creating more jobs building solar farms, wind farms and other facilities.

Lawmakers could also prompt the Public Utilities Commission to more quickly distribute $1.2 billion in incentives for rooftop solar panels and batteries, which could help Californians keep the lights on during fire-prevention power outages this year.

“We may need to make regulatory changes to get those kinds of dollars out the door,” Stern said.

At the federal level, a coalition of local governments, utilities and auto companies — led by the Los Angeles Cleantech Incubator — is pushing a stimulus plan that calls for $150 billion in federal investment to support to support electric cars and public transit.

The plan includes $25 billion in tax credits and other incentives for buyers and manufacturers of clean vehicles; $85 billion for grid upgrades to support chargers for electric cars, trucks and buses; and $12.5 billion for workforce development and job training.

Gasoline-powered cars and trucks are California’s largest source of climate-changing emissions and the primary cause of Los Angeles’ infamous, lung-damaging smog. Stay-at-home orders and spring rains brought cleaner air and a crisper skyline to the L.A. area in March. But air pollution returned to unhealthy levels for much of April, and traffic is already starting to pick back up.

Cleaning up the transportation sector is especially important given the emerging research suggesting that breathing dirty air makes people more likely to die of COVID-19, said Matt Petersen, president of the Los Angeles Cleantech Incubator.

Clean vehicles are also a proven job creator, he said, with companies including BYD, Proterra and Tesla operating manufacturing plants in California and most major automakers planning to invest billions of dollars in cars and trucks that don’t use gasoline.

The proposed federal stimulus “will create hundreds of thousands of jobs, restart the economy and accelerate growth, support entrepreneurs and the innovation economy, reduce air pollution, and protect vulnerable populations,” Petersen wrote in April.

In a national poll last month, the left-leaning firm Navigator Research found that 76% of registered voters support “investing in the creation of energy efficient infrastructure and the jobs to transition to clean energy.” Support was at 66% among Republicans.

Still, the Republican-controlled U.S. Senate is unlikely to make clean energy stimulus a priority. The same goes for Trump, whose administration has unwound dozens of regulations designed to limit fossil fuels or support renewable power.

Solar and wind energy companies are holding out hope for some federal support.

The U.S. Treasury Department indicated last week that it will extend the “safe harbor” deadline for wind farm projects, giving developers an additional year to finish construction without losing full eligibility for federal production tax credits. Renewable energy trade groups have asked Congress to provide additional relief by allowing solar and wind companies to take advantage of tax credits even if they can’t get tax equity financing, as lawmakers did in 2009 during the height of the Great Recession.

Congress approved $90 billion for clean energy during the Great Recession, providing a model for how lawmakers might boost the economy amid COVID-19.

Supporters of more sweeping climate and clean energy policies, such as the Green New Deal, are thinking bigger.

Hundreds of nonprofits have signed on to the Five Principles of Just COVID-19 Relief and Stimulus, a set of proposals prepared by groups including Greenpeace, the Sierra Club, the Sunrise Movement and the Service Employees International Union.

The document calls for public investments to “replace lead pipes, expand wind and solar power, build clean and affordable public transit, weatherize our buildings, build and repair public housing, manufacture more clean energy goods, restore our wetlands and forests, expand public services that support climate resilience, and support regenerative agriculture led by family farmers.”

“The response to one existential crisis must not fuel another,” the document reads.