Taking an Uber or Lyft pollutes more than driving, California finds. Next stop: Regulations

- Share via

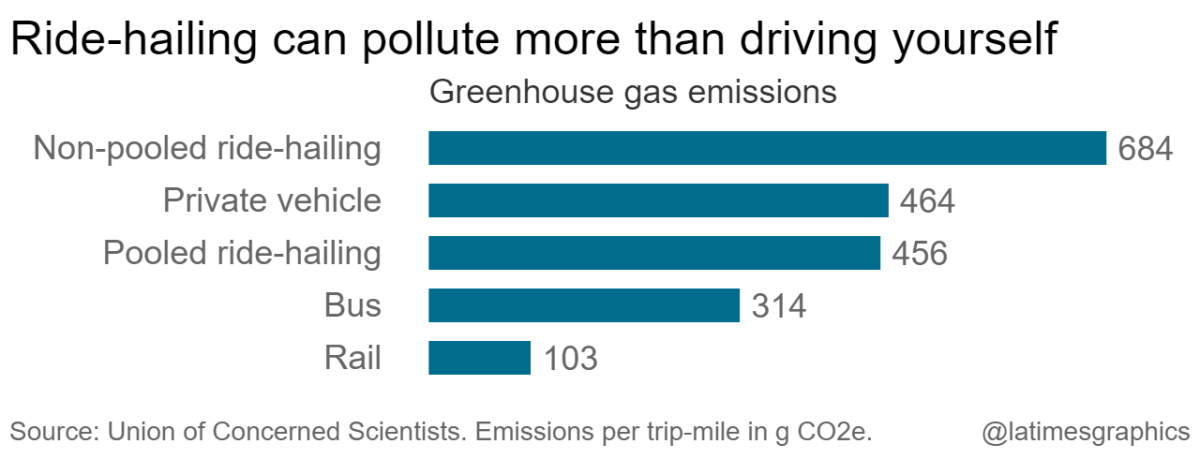

Behind the tap-of-your-phone convenience of hailing an Uber or Lyft lies an inconvenient truth: Such rides generate more carbon emissions than simply driving yourself.

The increased pollution comes primarily from “deadheading,” that is, drivers traveling to pick up a passenger or cruising the streets while waiting for a ride request. Deadheading accounts for about 40% of the miles logged by Uber and Lyft vehicles in California, according to recent analysis by state air quality regulators.

“That means that for a one-mile trip, on average there’s about another 0.7 miles of driving around to deliver that trip,” said Don Anair, clean vehicles program research director for the Union of Concerned Scientists, an environmental group that recently released its own report backing up some of the state’s findings. “People don’t see that. They only see the vehicle pull up and they take their trip.”

But the status quo may not hold for long. The California Air Resources Board is now developing the world’s first regulations to reduce the climate impacts of ride hailing. The rules, expected by year’s end, seek to rein in traffic and pollution from an industry that has quickly risen to overtake taxis, in large part by avoiding regulation to begin with.

There are more than 600,000 ride-hail vehicles in California, and they emit about 50% more greenhouse gas emissions per passenger mile traveled than an average car statewide, according to an analysis released by air quality officials in December.

The Union of Concerned Scientists study, however, concluded that ride hailing is even worse for the climate than air quality officials found. That’s because riders aren’t only taking Uber or Lyft instead of their own private vehicles, they’re taking them when they otherwise would have used lower-carbon options such as public transit, biking or walking.

When you factor in displacement of cleaner transportation, a typical ride-hail trip is about 70% more polluting than the average trip it replaces, the group’s analysis found.

Ride-hail companies have the ability to reduce their emissions by providing subsidies to help drivers buy or lease electric cars, for example. But Uber and Lyft are already under pressure from investors to stem hefty losses that have raised questions about their business model. If they convert quickly to electric cars, it could drive up costs for hailing a ride — a prospect that worries some customers.

“Uber’s not going to pay. So they’ll pass it down to us,” said Mukaila Kazeem, 36, of Long Beach, who occasionally uses Uber or Lyft to get to the airport or concerts at the Hollywood Bowl. “There’s no way to regulate, or fix this, without someone paying more.”

The move to regulate ride hailing is a result of Senate Bill 1014, the 2018 law that requires California regulators to impose rules to reduce the industry’s greenhouse gas emissions.

“We’re trying to be leaders in stopping the climate crisis,” said state Sen. Nancy Skinner (D-Berkeley), who authored the legislation. “Having these convenient cars belching out fossil-fuel fumes is not helping us.”

Skinner’s bill was initially drafted with a statewide goal of transitioning the ride-hail fleet to 100% zero-emission vehicles by 2029, but that language was removed by state lawmakers. That leaves it to state regulators to formulate the targets.

That’s OK because it provides flexibility, Skinner said. “Maybe the original goal they set for ride-hailing companies is lower than I had in mind, but if they increase it over time, will still achieve the objective.”

The Air Resources Board’s emissions estimates, based on detailed, confidential data Lyft and Uber provided under the law, showed the 640,000 ride-hail vehicles operating in California in 2018 released only a small fraction of the state’s carbon emissions, accounting for about 1% of vehicle miles and greenhouse gas emissions from light-duty vehicles.

Regulators said they are nonetheless concerned about increased pollution from an industry that has grown exponentially since Uber introduced the service in 2010. Less than 1% of the miles traveled are electric, or zero emission, the air board’s analysis found.

The Air Resources Board staff plans to bring the rules to the 16-member panel toward the end of this year.

Starting in 2023, the state would begin imposing increasingly stringent pollution standards, along with the requirement that the percentage of number of miles driven in electric vehicles grows over time. The approach will also include measures to encourage better integration with public transit and increased use of pooled rides — two strategies that experts say can push carbon emissions from ride-hail trips lower than private cars.

“This is a really groundbreaking regulation,” Air Resources Board Chair Mary Nichols said at a public meeting in January. “And it’s part of our multi-pronged strategy to reduce emissions from passenger transportation.”

Slashing transportation pollution remains one of California’s most vexing climate challenges. The sector is the state’s largest source of planet-warming emissions, accounting for about 40% of the statewide total, and and that output has been rising the last few years. Passenger vehicles make up the bulk, contributing about 28% of the state’s total greenhouse gas emissions.

Even with growing numbers of electric vehicles, California will not reach its goal of cutting greenhouse gases 40% below 1990 levels by 2030 without reducing vehicle miles traveled.

Environmental groups such as the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Sierra Club are urging the Air Resources Board to draft ride-hail rules that achieve the same goal initially sought in the legislation, including a target that achieves 100% electrification by 2030.

At the January hearing, Austin Heyworth, Uber’s senior manager of public policy for California, said the company supports the regulation.

“We remain a small portion of [vehicle miles traveled] and light-duty emissions, but we’re up to the challenge, as an industry, of having this applied to us first,” Heyworth said.

Lyft spokeswoman Campbell Matthews said in a statement that the company “is striving to make every ride 100% electric over time” and is also encouraging use of shared rides and public transit in conjunction with ride hailing.

Nicole Moore, a healthcare worker who lives in the San Gabriel Valley and works about 20 hours a week driving her plug-in hybrid for Lyft, said low occupancy is a big obstacle to increasing driver earnings and easing pollution.

“There’s nights where I drive down a busy boulevard in L.A. and more than three-quarters of the cars have Uber or Lyft stickers on them. I’ve counted them,” Moore said. The result, she added, is congestion, carbon emissions and drivers “not able to make a good living.”

Moore is a member of the organizing committee of Los Angeles-based Rideshare Drivers United, which is advocating for restrictions on the industry, including emissions standards and caps on the number of new vehicles joining the fleet.

“We’re lucky if we have 40% occupancy, so that means 60% of the time our app is on we don’t have anybody in the car,” Moore said. She said she wants to be part of the solution, “but as drivers we have almost no control over what’s happening. ... The responsibility for this rests with the companies.”

Research since about 2016 has shown that ride hailing is fueling some of the increase in driving and congestion, most notably in busy urban centers.

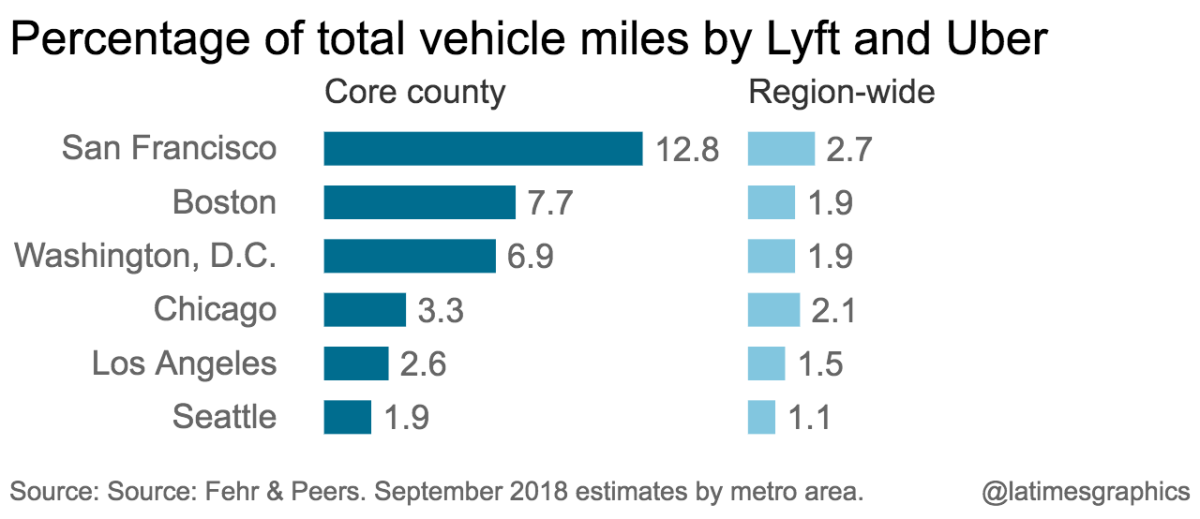

An analysis of six U.S. metro areas last year by the consulting firm Fehr & Peers, commissioned by Uber and Lyft, found that while ride hailing makes up only about 2% of miles driven overall, that percentage can be much higher in the urban core. In San Francisco, the analysis found that about 13% of vehicle miles were generated by Uber and Lyft.

Taxis also log a lot of deadheading miles, but they have long faced an array of local and environmental restrictions. In Los Angeles, they are are subject to model-year restrictions that bar older, more polluting vehicles.

And starting in July, L.A.’s Department of Transportation will prohibit solely gas-powered taxis from joining the fleet, allowing only clean-air models like hybrids or electric cars.

In California, ride-hail services are under the jurisdiction of the state Public Utilities Commission, and local governments are barred from regulating them.

In recent comments, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti has said the city has some power to regulate ride-hail companies and is looking at ways to force them to use electric vehicles.

“The mayor’s office is already at the table with ride-hailing companies like Uber and Lyft, as well as charging providers, to work on electrifying ride-hailing vehicles, and we’re advocating for regulatory reforms at the state level,” Harrison Wollman, a spokesman for Garcetti, said in an email.

Other U.S. cities have moved to address the traffic impacts of Uber and Lyft. Chicago imposed a tax on trips downtown to encourage pooled rides and public transit, and New York has capped the number of ride-hail vehicles in an effort to ease congestion.

“Ours is the first one that is an environmental performance metric,” said Joshua Cunningham, chief of the state Air Resources Board’s Advanced Clean Cars Branch. “We think that this approach is more comprehensive.”

Washington state could follow suit. A bill in that state’s Legislature would launch similar programs to cut carbon emissions from ride hailing.

There are some indications that the industry’s pollution could be dialed back without too much difficulty. The state’s analysis shows vehicles in the ride-hailing fleet, as a whole, are already are more efficient that the statewide average, with a higher percentage of newer, more fuel-efficient cars and hybrids.

When Uber and Lyft trips are pooled, made in electric vehicles or combined with public transit, their carbon emissions dip below that of typical private vehicle trips, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists.

That means the biggest benefit would come from electrification and increasing pooled rides, said Anair of the Union of Concerned Scientists. He commended the ride-hail companies for launching some pilot projects aimed at getting more electric vehicles into their fleet, but says such initiatives have not been done on nearly a large enough scale.

“To get on track, it’s really going to take a concerted effort and investment,” Anair said.