They’re knee deep in the climate trenches. Here’s what gives them hope

- Share via

This is the Nov. 24, 2022, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

You’re probably just as tired of reading dire climate change news as I am of writing it.

So this week — when we’re all doing our best to practice gratitude and remind ourselves of the good things in life, and eat some delicious food — let’s try something different: Let’s talk hope.

Last year on Thanksgiving, I asked my L.A. Times colleagues who write about environmental calamity what gives them hope. This year, I reached out to nine people who work on environmental issues or who otherwise deal with the climate crisis in their professional lives. I asked them what makes them optimistic, what keeps them going.

Here’s what they had to say.

Kim Delfino, founder and president, Earth Advocacy

Working to protect biodiversity — all creatures great and small — in the face of climate change can be daunting.

But I remain hopeful because I work in a state where we are leading by doing, and everyday people are striving for that better future. California has set important goals to grow clean energy, reverse the extinction crisis and protect our lands and waters for the benefit of all. We are the first state to implement a plan to protect 30% of our lands and waters by 2030, as part of a global effort to conserve biodiversity and build climate resilience.

Achieving California’s ambitious goals is an enormous challenge. But scientists, lawyers, organizers, legislators and their staff, government leaders, academics, students and so many others get up each day thinking about how to do better, be better and make the changes we need to tackle these tough problems.

It is not difficult to be optimistic when you work with people who see the challenges ahead and persevere because they know that a better future will happen only through hard work, dedication, and (to steal a line from a colleague) endless pressure, endlessly applied.

Chris Dickerson, co-founder, Players for the Planet

If Michael Jordan, Leo Messi, Serena Williams, Tiger Woods, Tom Brady and Wayne Gretzky put together a comprehensive report on how to play their sports, it would fly off the shelves. Yet we discount top scientists when they file their climate reports.

I spoke at the United Nations when I played for the Cincinnati Reds, before the 2009 climate conference. Thirteen years later, millions of lives have been sacrificed by continued corporate greed and irresponsibility.

Athletes around the world have told me stories about how the climate is changing all around them. They’re experiencing warming water, lack of rainfall, more extreme weather, early melting of ice/snowpack and increasing temperatures. So I know we’re too late to solve the climate crisis. But I am determined. I am optimistic about the power of sport.

Sport is a great unifier, transcending political, cultural, religious and socioeconomic barriers. It can wield a uniquely powerful influence, providing leadership in sustainable practices and demonstrating a nonpolitical commitment to environmental protection. Sport also has the ability to leverage its power by demanding action from its corporate sponsors.

Teams, leagues and professional athletes must hold themselves to a higher set of values and responsibilities.

Peter Gleick, co-founder and president emeritus, Pacific Institute

There is a difference between having hope and being hopeful.

I’ve always been an optimist — it is what has let me continue to work on issues of climate change, water resources and resource conflicts for more than 40 years. I’m hopeful that, over time, we — the world — will act on the clear and definitive information about the threats posed by global climate change, inequities and resource mismanagement and depletion.

I see signs that the world is beginning to act (though faster is always better). I also hope that it rains this year in the Western U.S., that our progress in moving to more sustainable water management continues and accelerates, and that the voices of delay and denial are drowned out by the voices of science, reason and action.

Mark Hertsgaard, executive director, Covering Climate Now

Hope is a choice. It is a verb. It is not simply a feeling but a decision about how to live one’s life.

With climate change, hope is usually framed as a question about the future. I find hope in the past.

As a journalist, I’ve interviewed such giants of hope as Vaclav Havel, who helped bring democracy to the former Soviet Union. I visited Robben Island, where Nelson Mandela was imprisoned for many years before South Africa’s apartheid regime was forced to free him. My latest book investigates slavery in the American South.

A strictly rational person would have seen no hope that totalitarianism, apartheid or slavery would ever fall. But fall they did because Havel, Mandela and thousands of others chose hope over despair — not because they knew they would win, but because choosing hope was the only way they might win.

Every one of us can make that same choice today about the climate emergency. Young people are leading the way. That is hope in action.

Julian Brave NoiseCat, writer and filmmaker

Last week, I was invited by First Lady Jill Biden to the White House. In grand rooms decorated with portraits of U.S. presidents and American Indian chiefs, a couple of hundred Indigenous people gathered for the first White House celebration of Native American Heritage Month.

“Indigenous peoples are at the decision-making table,” Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American Cabinet secretary, said in her remarks to attendees. “And we’re not going back!”

I was the first to publicly suggest Haaland should be nominated for her role. As a writer, I had the opportunity to profile her and to help make the case for her historic appointment. Haaland now leads a department that manages one-fifth of the nation’s landmass and vast reserves of natural resources, as well as government-to-government relationships with more than 570 federally recognized tribes.

The fact that Thanksgiving and Native American Heritage Month both fall in November has long felt like a cruel irony. The pilgrims took a lot over the last 400 years. But these days I’m bullish on the possibility that we just might get back what was ours.

Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, assistant professor, University of New Hampshire

I’m a theoretical astro/physicist who grew up in smoggy 1980s East L.A., right next to the 10 Freeway. My part of El Sereno, broken off from the rest by industrial train tracks, had no parks within reasonable walking or biking distance.

Across the U.S., kids like me are taught to hope for the opportunity to escape our communities. Today, I imagine other possibilities: for kids like me to have everything they need, right where they are. That is why I am pleased to follow the work of the Atlanta Forest Defenders, who are protecting the largest tree canopy in any major U.S. city.

The Atlanta Police Department plans to desecrate Weelaunee Forest with a new training facility. So far, a cross-community coalition of Indigenous people, Black people and other prison abolitionists and environmental protectors has succeeded in stopping the project. They articulate themselves as “an autonomous movement for the future of South Atlanta.” To me, they are hope.

Terry Tempest Williams, environmental writer and activist

Each morning when I watch the sun rise in Utah’s red rock desert and illuminate Adobe Mesa, I see a fresh day before me. And the setting sun that sinks behind Porcupine Rim creates an encore light on Castleton Tower that is swoon-worthy. I am alive with gratitude.

What happens in between dawn and dusk is something deeper than hope. For me, it has everything to do with how we choose to engage with a world on fire. Meeting fire with fire is one strategy. Find your fire — what you are passionate about — and create a backburn to meet the encroaching flames. Where they dance is where the sparks of change are born. Earth vows take root in the clearing.

Aura Vasquez, community organizer, former L.A. Department of Water and Power commissioner

In my neighborhood, children don’t get to play in parks. Instead, families set up kiddie pools between cars so their kids can cool down on hot weekends and summer days. Many can see their school across the street, vacant and unused, behind locked gates.

Children struggle to find green spaces in Mid-City and most low-income L.A. neighborhoods. Most city parks are far from home and often require crossing major thoroughfares. During the pandemic, not having a park or playground hurt children’s physical and mental health even more. With high real estate costs, demand to increase apartment stock and lack of appetite to build parks, some residents have begun to give up on any demand for green spaces.

That’s why a group of neighbors and I started Ready to Help Mutual Aid Community Network. We organized to pressure city officials, demanding they allow school playgrounds to open as parks on evenings and weekends, and offer new outdoor and beautification programs.

There’s a lot of work left to do, but our pilot program at Alta Loma Elementary School led to 20 other community school parks opening their gates. And that gives me so much hope.

V. John White, executive director, Center for Energy Efficiency and Renewable Technologies

As we prepare for the Thanksgiving holiday, I choose to be optimistic and grateful for our recent progress on climate action, and the strong leadership of President Biden and his superb climate team.

I believe the Inflation Reduction Act is a game-changer for the economics of clean energy and climate action. The 10-year extension of tax credits for clean energy, storage and other technologies is crucial, especially when combined with the authority given to federal agencies to partner with states and utilities to build new transmission lines.

I am also grateful for the continuing leadership of California. Despite recent setbacks with delayed retirement of old dirty gas plants and continuing reliance on dirty diesel backup, California knows what it needs to do to build out the infrastructure of clean energy, storage, distributed solar and fuel cells, expand energy efficiency and demand response, and hopefully retire the oldest, least-efficient gas plants in environmental justice communities such as Oxnard.

Most of all, I am optimistic about the passion and commitment of young Generation Z and millennial voters to transform the political landscape and accelerate climate action in time to stave off the worsening effects of global warming.

**

And yes, we’ve still got our normal news roundup below — the good and the bad, the ugly and the beautiful. But if you can, try to keep some perspective. All is not lost.

Happy Thanksgiving, however you might celebrate.

Here’s what’s happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

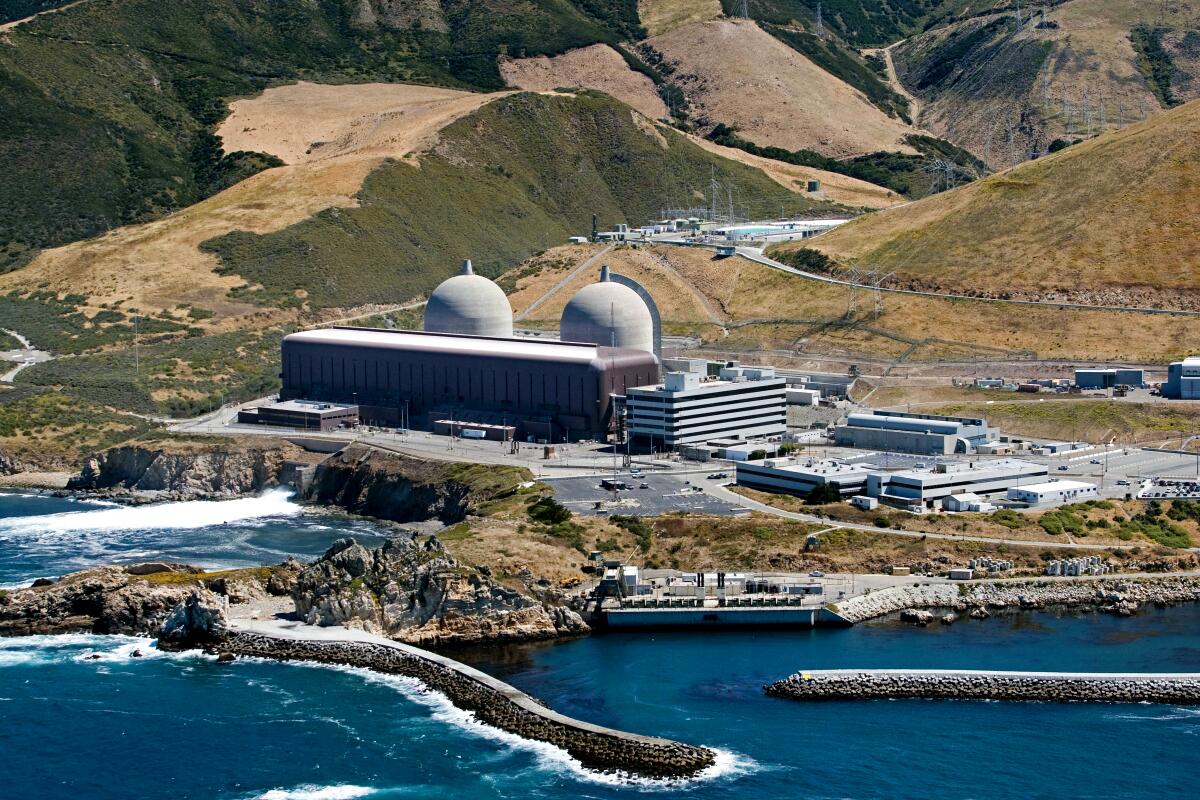

The Biden administration is dishing out $1.1 billion to rescue California’s last nuclear power plant. The money will help Pacific Gas & Electric keep operating the Diablo Canyon plant through 2030, five years past the facility’s current planned closing date — assuming PG&E can get its federal license renewed and secure a bunch of state approvals, as I reported for The Times. Whether Diablo Canyon is a badly needed climate solution that will help California keep the lights on or a radioactive disaster waiting to happen is, as always, the subject of intense debate. In other nuclear news, New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham is urging President Biden to block a proposed nuclear waste storage site in her state, per Adrian Hedden of the Carlsbad Current-Argus.

It’s official: The Klamath River dams are coming down. Four dams along the California-Oregon border will be demolished at a cost of $500 million, marking the largest dam removal project in U.S. history. Here’s the story from my colleague Hayley Smith, who writes that federal regulators approved the long-awaited demolition to restore a free-flowing river for salmon and other fish valued by Indigenous tribes and commercial fisherfolk. In other dam news, a $2.5-billion plan for the first new large reservoir in the San Francisco Bay Area in 20 years could be dead, as a key supporter of the proposed Pacheco Dam lost reelection at Santa Clara Valley Water District. Details here from Paul Rogers of the Mercury News.

California got lucky not to have a much more destructive fire season in 2022 — but forest thinning and prescribed burns are starting to help too. Hayley Smith wrote about what went right this year — and what went wrong, including the deaths of nine people, six more than last year though far fewer acres burned. In other wildfire news, the U.S. Forest Service knew for decades that the small Sierra Nevada community of Grizzly Flats could be destroyed by flames — but the agency didn’t get far on its plan to protect the town, and then it was too late. Members of Congress are demanding answers after an investigation by Scott Rodd for CapRadio and the California Newsroom.

Climbing Mt. Kilimanjaro is still an epic experience — but it’s not what it once was. The Times’ Jack Dolan summited Africa’s highest peak and wrote about the startling dearth of ice and snow, as global warming melts Kilimanjaro’s iconic glaciers.

WATER IN THE WEST

California officials approved another seawater desalination plant — despite significant environmental justice concerns. The Times’ Rosanna Xia wrote about the Coastal Commission’s 8-2 vote in favor of an investor-owned water utility’s Monterey Bay desalination project, and why residents of Marina — a low-income town where many speak little English — are still fighting to block the facility. “First it was land, now water,” Marina resident Monica Tran Kim said. “It’s a historical repeat of people in power taking what’s valuable from a community that they don’t see as deserving — from a community that is vulnerable.”

Scientists are discovering hidden underground rivers in California’s Central Valley where it’s way easier to recharge depleted groundwater aquifers. My colleague Ian James wrote about the super cool technique being used to uncover these “paleovalleys,” which involves flying helicopters equipped with electromagnetic imaging systems. As farms and cities drain the Central Valley’s groundwater — and as climate change intensifies the state’s swings between drought and flood — it will be increasingly important to identify these sites, where floodwaters can be be funneled to recharge aquifers. That banked water would be especially valuable for years like this one, when the Central Valley is so dry that the state will harvest its smallest rice crop in more than 40 years, as James reports.

Thirty urban water suppliers from Santa Monica to Denver have reached an important agreement: Decorative grass has got to go. Those agencies have committed to a nonbinding list of water-saving actions, Ian James writes, including removing 30% of “nonfunctional” grass and replacing it with “drought- and climate-resilient landscaping, while maintaining vital urban landscapes and tree canopies.” Here’s hoping they follow through. Elsewhere in the Colorado River Basin, the small Arizona city of Page has nowhere near the $46 million needed to protect its water supply as Lake Powell storage falls, KUNC’s Alex Hager reports — despite being located literally along the banks of the massive reservoir.

GIVING THANKS FOR WILDLIFE

Desert tortoises have been protected under the California Endangered Species Act for three decades — yet populations continue to decline. L.A. Times reporter Louis Sahagún and photographer Irfan Khan trekked out into the Mojave to find out why, and what’s being done to save the tortoise. They visited a nature preserve where biologists are tracking tortoise movements and a sewage treatment plant where a biologist works to scare away ravens with lasers. Yes, lasers. If you want to see the scientists in action, check out this thought-provoking and occasionally hilarious video by Jackeline Luna and Maggie Beidelman.

The U.S. has long guaranteed Pacific Northwest tribes their traditional fishing rights — but those rights are diminished by dangerous chemicals and metals in salmon and other fish, and government agencies aren’t even testing for those contaminants. So Oregon Public Broadcasting and ProPublica did their own testing and found worrisomely high levels of mercury and PCBs, which can cause serious long-term health problems. (Story by OPB’s Tony Schick and ProPublica’s Maya Miller.) In other Indigenous water news, High Country News and Grist wrote about how Western tribes are fighting to claim their long-promised rights to Colorado River water — in part by compiling crucial data that federal surveys have long ignored.

The Trump administration ended a long-running study process for reintroducing grizzly bears to the North Cascades. Now the Biden administration is getting the process started again. “This is a first step toward bringing balance back to the ecosystem,” said Don Striker, superintendent of North Cascades National Park, as reported by the Washington Post’s Justine McDaniel. Elsewhere in the West, the Biden administration is protecting the lesser prairie chicken under the Endangered Species Act, long a priority of conservation groups — but with special provisions that will allow agriculture, livestock grazing and controlled burns to continue killing the endangered birds, per Scott Streater of E&E News.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

To make up for environmental damage from solar farms in the California desert, developer Avantus has purchased and permanently retired grazing rights across 215,000 acres of federal land in Kern County. Details here from John Cox of the Bakersfield Californian, who notes that some ranchers are troubled to see so much land set aside for conservation. It’s a unique attempt to accelerate the much-needed renewable energy buildout while protecting wildlife habitat, with Kern County’s planning director calling it “another example of trying to rebalance all these priorities.”

Montana’s largest wind farm is up and running, and sending electricity to Washington state. By the time it’s fully built out next year, the plant will have 750 megawatts of capacity and supply Portland too, Tom Lutey reports for the Billings Gazette. The wind farm is helping to replace Montana’s Colstrip coal plant, which is moving toward possible closure in 2025. In Utah, meanwhile, the Biden administration is defending a Trump-era plan that would allow continued haze pollution from two other coal plants, both of them owned by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Energy. Here’s the story from Sean Reilly of E&E News.

Two microgrid suburbs are being built in California’s Inland Empire, with homes featuring solar panels on roofs, batteries in garages, induction stoves, heat pumps and smart electrical panels. There’s also a big community battery — and, crucially, the ability to “island” the neighborhoods from the larger power grid, meaning they can keep the lights on even when there’s a large-scale power outage in the region, as Todd Woody reports in a fascinating story for Bloomberg. This is what the grid of the future looks like — a lot more big solar and wind farms, almost certainly, but also communities creating their own clean energy ecosystems.

ONE MORE THING

If you’re wondering where California’s energy comes from — or if you want to see me explain climate solutions using a pumpkin pie — have we got the video for you! Thanks much to my colleagues Jessica Q. Chen and Maggie Beidelman for producing this fun and smart Instagram reel in which I show off my lousy pie-slicing skills and nerd out about energy data.

You can also watch the video on YouTube.

ACTUALLY, JUST ONE MORE

Remember all those viral stories about the National Park Service warning people not to lick Sonoran desert toads in an attempt to get high? Well, it turns out that Facebook post from the park service — shared on Halloween — was actually a joke. Thanks very much to the Colorado Sun’s Jason Blevins for confirming, and for validating my instinct that something wasn’t quite right.

OK, that’s enough. Enjoy Thanksgiving, everybody.

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, or previous ones, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues. For more climate and environment news, follow me on Twitter @Sammy_Roth.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.