Every election is a climate election. The midterms were no exception

- Share via

This is the Nov. 10, 2022, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

The last time Democrats tried to pass a major climate bill in Congress, it was so unpopular that a Democratic Senate candidate in West Virginia — a guy by the name of Joe Manchin III — ran a TV ad where he literally shot a hole through the bill.

That was 12 years ago. A lot has changed about climate politics since then.

Democrats finally passed sweeping climate legislation, with Manchin throwing his support behind the Inflation Reduction Act and President Biden signing the bill in August. But despite that vote coming less than three months before the midterm elections, climate change did not play a significant role in most congressional campaigns. Across the country, just 15% of ads mentioned energy or the environment in September, rising slightly to 18% in October, according to a Wesleyan Media Project analysis.

That lack of climate focus is almost certainly a sign that aggressive steps to tackle global warming aren’t as controversial as they used to be. A Pew Research Center survey in May found 58% of Americans thought the federal government was doing too little to combat the climate crisis. Among Democrats, that number was 82%. Even among young Republicans (ages 18-29), 47% said the Biden administration wasn’t doing enough on climate.

“The fact that Republicans were not running against climate change, I think was the single most telling thing in this election,” said Edward Maibach, director of George Mason University’s Center for Climate Change Communication.

On the flip side, Maibach thinks Democrats nationwide largely missed an opportunity to campaign on their climate achievements. Rather than highlight popular clean energy spending in the Inflation Reduction Act — including financial incentives for technologies that can save people money, such as rooftop solar panels, electric cars and electric heat pumps — many Democrats “ran scared,” Maibach said, playing defense against Republican attacks on issues such as inflation, gas prices and crime.

“The team that should have gotten the memo about running on climate doesn’t seem to have gotten the memo,” he said.

Even if he’s right, climate still isn’t nearly as important to the electorate as the science tells us it ought to be.

YouGov tracking polls over the last year have found about 10% of registered voters list climate and the environment as their most important issue, with the numbers typically only a few percentage points higher among voters under 30. In an Associated Press exit poll, just 8% of midterm voters named global warming as the most important issue facing the county.

Meanwhile, “climate hazards and cascading climate impacts are disrupting essential societal systems in every part of the country,” according to a draft of the latest National Climate Assessment, released by federal scientists this week. “Communities that are already overburdened experience harmful impacts first and worst, exacerbating existing inequalities.”

That’s certainly true in California, where bigger and more destructive fires, increasingly intense swings between drought and flood, ever-deadlier heat waves and the steadily encroaching Pacific Ocean have become unavoidable facts of life.

And yet, even here, climate is just one of many competing priorities. Voters soundly rejected Proposition 30, which would have raised taxes on the wealthy to pay for tens of billions of dollars’ worth of electric car subsidies and charging stations.

Jamal Raad, executive director of climate advocacy group Evergreen Action, sees reasons for optimism.

He pointed to several governor races as signs that climate is a winning issue. In the Upper Midwest, incumbent Democrats who campaigned on policies to slash greenhouse gas pollution defeated Republican challengers, with Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer highlighting her work to bring electric vehicle battery manufacturing to the state, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz rolling out his climate strategy a week before early voting began and Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers releasing the state’s first clean energy plan.

Democrats also took control of statehouses in Michigan and Minnesota. And in Maryland and Massachusetts, voters replaced moderate Republicans with Democrats from whom clean energy advocates expect big things.

With decent odds that at least one chamber of Congress is controlled by Republicans — votes are still being counted in many key races — state-level climate action will be especially important, Raad said. In part, that’s because it will be up to state officials to apply for much of the $370 billion in climate and clean energy funds made available through Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act — and then figure out how to distribute the money to the communities that need it most.

“That just got a lot easier with solid state leadership being elected across the country,” Raad said.

In Nevada, incumbent Gov. Steve Sisolak, a Democrat and renewable energy supporter, was running several points behind Trump-backed Republican Joe Lombardo as vote counting continued Wednesday. And in Oregon, a blue state, Democratic gubernatorial candidate Dina Koten barely fended off Republican Christine Drazan, who had pledged to “tear up” a key climate policy.

Still, Raad marveled at how much the conversation has changed nationally since Manchin’s gun-toting TV ad back in 2010.

“We have more work to do on its salience as a political issue. No doubt about it. But it’s pretty remarkable how much the politics around climate have changed,” he said. “Democrats used their political capital on [climate] legislation and did not pay a price for it in the midterms. In fact, many of them leaned into their clean energy leadership.”

In California, a longtime leader on reducing emissions, the early election returns were a mixed bag.

Mary Creasman, chief executive of California Environmental Voters, told me she was “heartbroken” by the defeat of Proposition 30, which she said “would have been the biggest thing California had ever done on climate.” At the same time, she was heartened that none of her advocacy group’s “priority” candidates for state Legislature and Congress had lost — at least not yet. As of Wednesday afternoon, few of those 18 races had been called, and many of them were close.

Is that a sign of climate hope or an indication that even liberal California has a long way to go? The answer might be “both.” Many of those priority races, Creasman said, featured moderate Democrats backed by Big Oil money going up against liberals with smaller campaign war chests. It’s a reminder of the oil industry’s continued political influence in the Golden State.

“I spend all my time fighting moderate Democrats, as a climate-focused organization,” Creasman said.

One of those weak-on-climate moderates — at least in Creasman’s view — is Bob Hertzberg, the state senator who several years ago helped block a bill that would have banned oil and gas drilling near homes and schools. (He later supported a successful version of the bill backed by Gov. Gavin Newsom.) Hertzberg ran for Los Angeles County supervisor against Creasman’s preferred candidate, West Hollywood City Councilmember Lindsey Horvath, and he held a narrow lead Wednesday.

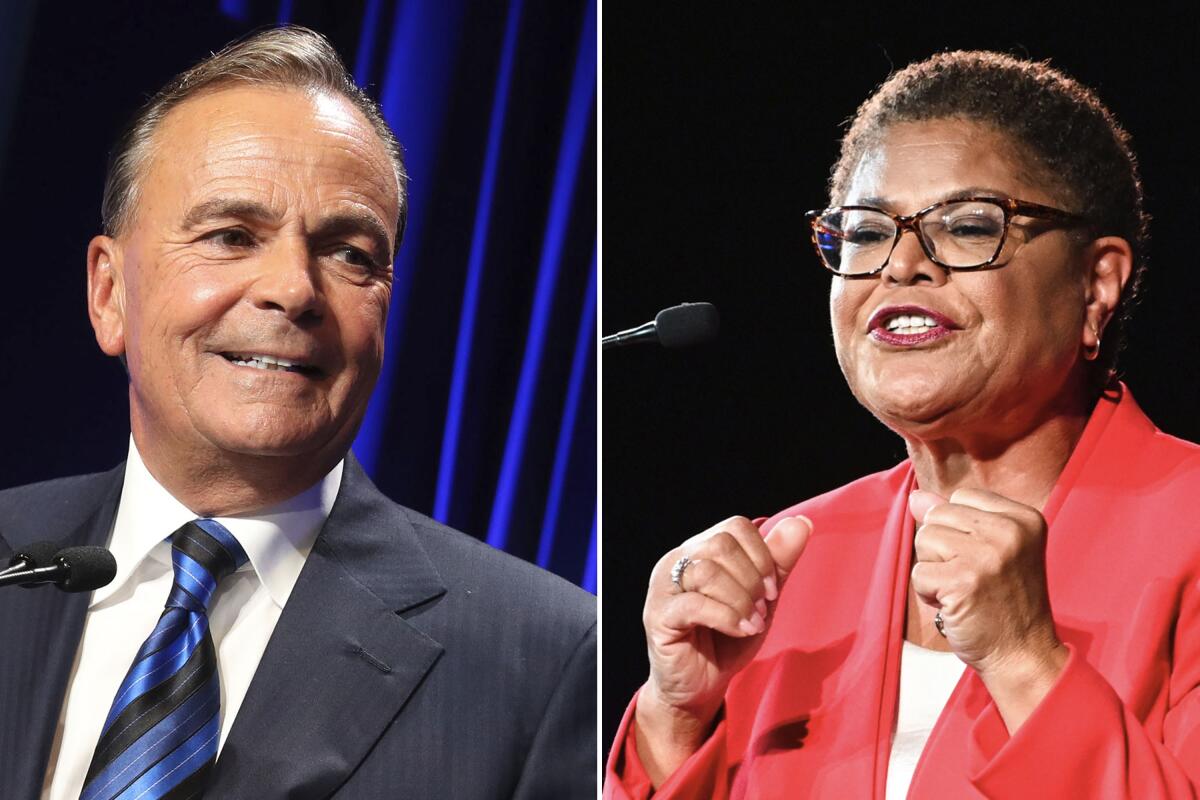

Also holding a narrow lead: Rick Caruso, the billionaire real estate developer running for L.A. mayor against U.S. Rep. Karen Bass. Caruso belatedly released a climate plan in September after months of criticism from activists, although his campaign didn’t grant my repeated requests to interview him about it. Clean energy advocates strongly favored Bass.

Whatever happens in those races, California has a long way to go on cutting pollution from cars, trucks and power plants.

“We are not meeting our climate goals,” Creasman said. “We have to quadruple our rate of carbon emissions reductions.”

I’ll have a full roundup on climate-relevant election results up and down the ballot across the West next week, after more votes have been counted. In the meantime, I’ll be watching to see what happens in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, where global leaders have converged this month for the latest United Nations climate conference. Biden is expected to tell the world that U.S. progress on climate will not be turned back following the midterm elections, even if Republicans win the House, Senate or both.

Is Biden right? Only time will tell.

But with more climate legislation unlikely in Congress the next two years either way, activists are looking to the White House to keep up momentum. The Environmental Protection Agency is drafting rules to limit air, water and climate pollution, although it’s fallen behind on many of them, activists say. And there are other ways the Biden administration could promote renewable energy, help homes replace gas heaters with electric heat pumps and require companies to disclose more about their emissions.

Biden could also block fossil fuel projects, such as ConocoPhillips’ $8-billion Willow oil drilling plan on public lands in Alaska, which needs a federal construction permit. Then there are pipelines, and natural gas export terminals such as the one Sempra Energy of San Diego is reportedly planning to build along the Gulf Coast. An analysis last year from advocacy group Oil Change International found Biden could prevent 400 coal plants’ worth of emissions by blocking two dozen proposed pipelines and export terminals.

So there’s a lot to talk about between now and the next national election, in November 2024 — at which point we’ll be nearly halfway through a decade in which scientists say global climate pollution needs to be cut nearly in half.

It’s a tall order. But it’s also the reality we live in. Maybe our politics will eventually catch up.

On that note, here’s what’s happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

The Supreme Court will consider overturning the Navajo Nation’s newly declared right to more water from the Colorado River. The high court is taking up the case at the urging of the Biden administration, the state of Arizona and Southern California’s biggest water agency, as The Times’ David G. Savage reports. If Southern California officials trying to take water away from the Navajo Nation surprises you — well, welcome to the fast-drying West. In related news, the Colorado Sun’s Chris Outcalt writes that groundwater levels in the Colorado River Basin are falling much faster than water levels at Lake Mead and Lake Powell — and groundwater pumping is contributing about as much to sea level rise as melting ice sheets, which, wow.

Washington state will require electric heat pumps in all newly built homes. Details here from Kip Hill at the Spokesman-Review. It’s a significant blow for the natural gas industry, which has been fighting to maintain its market share as activists push for climate-friendly heat pumps to replace planet-warming gas heaters. California hasn’t yet banned gas heaters (or stoves) in new homes, but Los Angeles is moving in that direction, as I reported in May. Looking across the country, companies including Airbnb, Lyft and Redfin are part of a new campaign to educate American homes about the electrification and energy-efficiency financing available to them through President Biden’s climate bill, per Alison F. Takemura at Canary Media.

A decision from California officials on rooftop solar incentives could be coming soon. The state’s Public Utilities Commission just announced it will hold oral arguments on the solar “net metering” program next week, as Rob Nikolewski reports for the San Diego Union-Tribune, and advocates on both side of the debate are taking that to mean a proposed decision is imminent. To catch up, see my piece from last year on the arguments for and against slashing payments to homes that go solar.

WATER IN THE WEST

Los Angeles is suing Owens Valley air pollution regulators, in the latest dispute stemming from L.A.’s deceitful campaign to dry up Owens Lake and take its water more than a century ago. The L.A. Department of Water and Power is accusing Owens Valley regulators of illegally ordering the city to tamp down dust particles blowing off a particular spot on the dry lakebed and attempting to fine the city $21 million for refusing to comply, The Times’ Louis Sahagún reports. Regardless of how this dispute plays out, Angelenos will be paying for dust control at Owens Lake for a long time — even if we stop taking so much water from it, which would benefit everybody. Speaking of using less water, L.A. residents consumed record-low amounts this summer, my colleague Dorany Pineda reports. And the city has just started offering $5 per square foot for residents to tear out grass lawns and replace them with drought-tolerant plants, up from $3 previously. Jon Healey has details on how to apply for the funds.

Drought is driving renewed interest in seawater desalination along the California coast — even though concerns about high costs and harm to marine life haven’t gone away. Here’s the story from my colleague Hayley Smith, who writes that new technologies and construction practices could limit environmental damage at least somewhat, and that other water sources are getting more expensive as the West gets drier. Desalination is also a hot topic on the Gulf Coast — including Corpus Christi, Texas, where Inside Climate News’ Dylan Baddour reports that officials have promised to invest in desalination to supply a plastics manufacturing plant being built by ExxonMobil, as well as other new industrial facilities — even as the city runs low on water.

The Sacramento Bee’s got an eye-opening investigation on the failure of California’s underfunded, understaffed regulators to police water diversions from the state’s major rivers — or even measure how much water is being taken out. The Bee’s story paints a picture of “a state regulatory system dramatically unprepared to address chronic water shortages and an ecosystem collapse,” as reporters Ryan Sabalow and Dale Kasler write. The regulatory agency in question is the State Water Resources Control Board. It’ll be interesting to see if lawmakers take these findings seriously and give the water board more funding.

ON OUR PUBLIC LANDS

After decades of battles between real estate developers and conservationists, the Trust for Public Land has acquired a gorgeous stretch of Southern California coastline north of Point Mugu. It’s got panoramic views of dolphins, sea lions and gray whales about an hour’s drive from Los Angeles, and will become part of the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, as The Times’ Louis Sahagún writes. He notes that the land is part of the Chumash people’s ancestral homeland.

“With tribal communities and other people of color, we want to ensure that everybody actually sees themselves in the parks.” So says National Park Service Director Chuck Sams, in a fascinating conversation with B. ‘Toastie’ Oaster at High Country News. They discuss incorporating Indigenous histories and land management practices into America’s national parks, and how the park service is responding to reports revealing a long history of sexual and racial harassment by employees.

All of Yosemite National Park’s glaciers, and Yellowstone’s ice patches, will be gone by 2050 — even if we somehow limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, according to a new UNESCO report. Details here from the Washington Post’s Rick Noack, if you can stomach them. The Yellowstone River, meanwhile, is considered the longest free-flowing river in the Lower 48 — even though it’s been straightjacketed by rock barriers holding its main channel in place. After this summer’s floods, property owners rebuilding along the river may make the problem worse, per Nick Mott at High Country News.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

In its largest grant ever to benefit a Native American tribe, California awarded $31 million to support construction of a long-duration energy storage system in San Diego County, with no lithium involved. The storage system will use zinc hybrid cathode batteries and help the Viejas Band of Kumeyaay Indians keep the lights on at its casino and other facilities during power outages — including intentional blackouts meant to prevent wildfire ignitions, as the San Diego Union-Tribune’s Rob Nikolewski reports. Batteries are already playing a crucial role on the California electric grid, with state officials reporting that 3.5 gigawatts of new storage helped avert rolling blackouts during the early-September heat wave, per Utility Dive’s Ethan Howland.

For the first time since strengthening its oil and gas regulations in 2019, Colorado rejected a drilling plan in a suburban community. But is it a sign the regulations are working, or not doing nearly enough? And will other states follow suit? I enjoyed this in-depth story by Mike Soraghan for E&E News. In other fossil fuel industry happenings, the San Francisco Chronicle’s Claire Hao writes that it’s difficult for the public to find out which California oil refineries are operating on any given day, and why some might be down for maintenance — and thus why gasoline prices might be going through the roof.

Four of the 10 most contaminated coal ash sites in the country are owned by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, and are likely polluting groundwater in Western states, a new analysis finds. Here’s the story from James Bruggers at Inside Climate News, based on an analysis by the Environmental Integrity Project and Earthjustice.

ONE MORE THING

In last week’s newsletter, I wrote about how few TV shows and films even mention the climate crisis, based on new research out of USC. By total coincidence, a few days later I watched a 15-year-old episode of my favorite show, “Scrubs,” in which global warming is a central plot point. The Season 7 episode, “My Inconvenient Truth,” features a viewing of Al Gore’s famous climate documentary, one character giving another character a hybrid car as a gift and extensive plugs for carpooling and recycling.

Do we need more television like this? Yes, yes we do.

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, or previous ones, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues. For more climate and environment news, follow me on Twitter @Sammy_Roth.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.