Solar and wind farms can hurt the environment. A new study offers solutions

- Share via

This is the Oct. 6, 2022, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

Let’s say we can solve the climate crisis. We can build all the clean energy infrastructure we need to replace fossil fuels over the next 30 years, and we can do it without triggering blackouts or causing electricity costs to rise too much.

Assuming that’s possible — would you be willing to pay 3% more on your energy bills to protect the natural world?

I didn’t pluck that number out of thin air. It comes from a new study by the Nature Conservancy, an environmental advocacy group, finding the American West can generate enough renewable power to tackle climate change even if some of its most ecologically valuable landscapes are placed off-limits to solar and wind farms — without causing costs to spiral out of control.

It’s an optimistic outlook — and a potent reminder of one of the biggest obstacles to renewable energy.

Yes, solar and wind have become just about the cheapest sources of new electricity on the market. And, yes, they were expanding rapidly even before President Biden signed a landmark climate bill in August that should supercharge their growth.

But finding places to build all the clean energy we’ll need to limit global warming isn’t getting any easier.

As developers flood rural communities and remote landscapes with proposals for solar fields and wind turbines, they often face intense opposition from conservationists dedicated to protecting habitat for migratory birds, sage grouse and desert tortoises — and from local residents who see industrial energy infrastructure as a threat to their small-town way of life.

That kind of opposition could slow or block clean energy development, resulting in climate catastrophe.

All of which brings us back to the Nature Conservancy study, which is currently finishing up peer review.

The study took an expansive look at the long-term clean energy needs of 11 Western states — including the charging needs of tens of millions of electric cars — and the land available to produce that clean energy. After running a series of gigantic models, the authors concluded that powering the West could require 26 million acres — an area roughly half the size of Utah.

But that finding assumed the only places off-limits to solar and wind farms were areas already protected by law, such as national parks and wildlife refuges. So the Nature Conservancy ran the models again, this time blocking renewable energy development in many other areas — including wetlands, critical habitat for endangered species and other lands identified by Nature Conservancy scientists as valuable for wildlife and humans, such as migration corridors and the best agricultural soils.

This time, the models spat out substantially different results. Under those limits, the West could meet its clean power needs with just 21 million acres of solar, wind and other zero-carbon resources. The overall cost would be $268 billion through 2050 — just 3% higher than the estimated $260-billion price tag without the additional land constraints.

Nicole Hill, the Nature Conservancy’s project manager, told me she was “genuinely surprised” the cost difference was so small. It’s a big deal, she said, because it means voters and politicians don’t have to choose between climate action and biodiversity.

“There is plenty of land to do this work,” she said.

The study mapped out several strategies for getting from 26 million acres down to 21 million.

One of them is building fewer wind farms in the West’s windiest states, particularly Wyoming, and more solar farms in the sunny desert Southwest. Wind farms require a lot more land area to produce the same amount of power, in part because wind turbines need to be spaced far apart. Solar farms have a smaller overall footprint by comparison.

The windiest spots also tend to be far from major population centers. Solar farms can be built closer to big cities with the biggest energy needs, including Los Angeles and Phoenix, meaning they require fewer miles of habitat-disrupting power lines.

Another key strategy: building more solar panels and wind turbines on agricultural land.

The Nature Conservancy reached a similar conclusion in a California-specific study a few years ago. The basic idea is that hundreds of millions of acres in the West have already been plowed and generally torn up, and it makes more sense to convert some of those lands to renewable energy than to pave over undisturbed habitat — especially in farm belts such as California’s San Joaquin Valley, where climate-fueled megadrought is leaving less water available for irrigating fields of crops.

Of course, reality is more complicated than a bunch of computer models. Agriculture is the economic cornerstone for many rural communities, not to mention the source of the food we eat. Across the country, small-town residents have rallied to protest proposed solar projects in particular, since those facilities often — but don’t always — preclude farming.

The Nature Conservancy took those concerns into account, excluding federally designated “prime farmland” from the modeling alongside valuable habitat. That left plenty of lower-quality agricultural areas for development, the authors said.

“Not all irrigated lands are created equal,” said Nels Johnson, the Nature Conservancy’s North America energy program director. “Some are on marginal soils, and they’re producing really low-value crops, while others are on really high-value soils.”

This kind of ecologically friendly energy strategy could have benefits beyond protecting wildlife.

For instance, developers who seek to build in less sensitive spots might be able to get government permits more quickly while reducing the likelihood of lawsuits. An earlier Nature Conservancy study, focused on California, found that solar farms proposed for lands with lower biodiversity got permitted nearly three times faster, helping accelerate the clean energy transition.

The key to making this all work in practice is collaboration and planning, the Nature Conservancy says. Western states must work together to map out where clean energy should be built and which lands should be protected, much like California did with the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan, Johnson told me.

“When you get a more collaborative approach to planning, you get fewer lawsuits, less conflict,” he said. “When people get a chance to help define what the future looks like, they’re much less likely to be resistant.”

Still, it’s just about impossible to build a solar or wind farm — or any other clean energy project — without at least some opposition. Collaboration and planning can go a long way, but they’ll never avert every land-use conflict.

It’s also important to acknowledge the tradeoffs inherent to the Nature Conservancy’s vision. If companies build fewer wind farms in Wyoming and more solar farms in California, it could be good for golden eagles and other birds flying through Wyoming — and bad for California desert species such as fringe-toed lizards and bighorn sheep.

“There’s no totally free lunch when it comes to deploying the level of infrastructure that we’re talking about,” Johnson said.

Still, there are ways to limit the damage. The more solar installations get built on lands already degraded by human activity — such as abandoned mines, Superfund sites, landfills and railroad corridors — the less pristine desert will be needed.

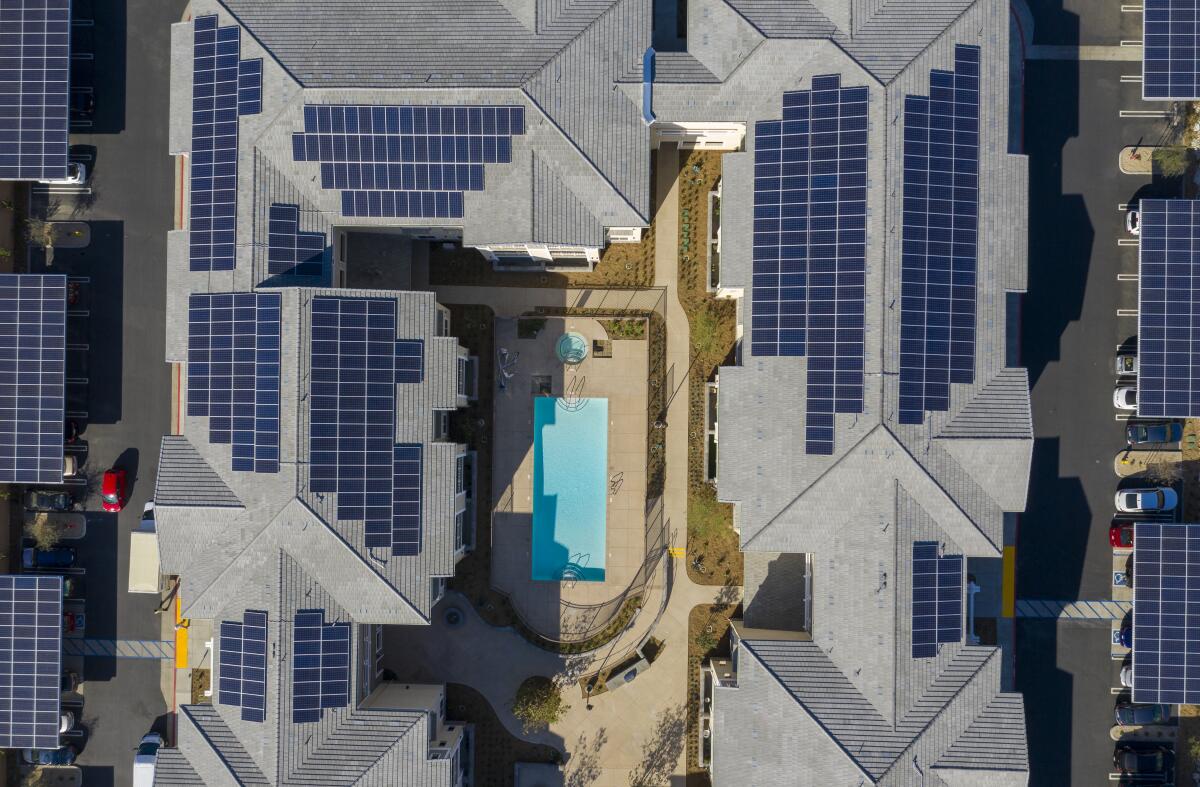

Solar panels on rooftops, warehouses and parking lots can also limit the need for desert development. The Nature Conservancy’s study assumes 35% of the West’s overall rooftop solar potential will actually get installed by 2050 — an ambitious target, although some rooftop solar supporters might argue we can do even better.

“Every megawatt [of rooftop] is one less megawatt we’re fighting over in an agricultural area or a natural area,” Johnson said.

Again, reality is more complicated than a computer model, especially once politics and economic self-interest come into play. Just see the many times unionized electrical workers have lobbied against rooftop solar in California because most rooftop solar companies are nonunion shops, and those union workers want to create more jobs for themselves building large solar farms.

Historical factors could also make it harder to balance climate action and conservation.

Dustin Mulvaney, an environmental studies professor at San Jose State University who has collaborated previously with the Nature Conservancy, told me he was encouraged by the new study’s findings. But he also pointed to the reality that solar and wind energy developers are constantly looking to build projects on public lands, including some of the highest-quality habitat left in the West — despite the opposition they often face from conservationists, and the seemingly not-so-high costs of building elsewhere.

One possible reason, Mulvaney said, is the existence of long-distance power lines that previously carried coal power to L.A. and other cities. Many of those lines were built across public lands — and now they have spare capacity as coal plants shut down.

Tapping into those lines is often the cheapest way for solar and wind developers to ship electricity to urban customers — as long as they build projects close enough to connect. In other words, as long as they build on the surrounding public lands.

“It opens up all these conflicts along these pathways,” Mulvaney said.

Mulvaney is hopeful the Nature Conservancy study will help chart a more sustainable future. He said the research could be especially useful for finding consensus on where to build new power lines — one of the most difficult and controversial aspects of the clean energy transition. The Nature Conservancy estimates a need for 6,259 miles of new power-line corridors.

That’s a lot of power lines. Then again, the U.S. did manage to build nearly 50,000 miles of interstate highways.

I’ll be continuing to cover climate change, clean energy and land use as part of our Repowering the West series. As always, please subscribe to The Times to support our work. And if you’ve got any questions, send me an email. I’ll do my best to reply.

On that note, here’s what else is happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

Remember from 2013 through 2015, when California had its three driest years on record? Well, that record didn’t last long. The “water year” came to an end Sept. 30, and officials say the state’s last three cycles around the sun were its driest since recordkeeping began in 1896, my colleague Hayley Smith reports. And while homes and farms alike have been forced to conserve, the lack of water has had its harshest consequences on California’s rivers and streams, and on the fish and other wildlife they support, Smith writes. If you’re a Los Angeles resident looking for more ways to cut back, and you live in a single-family home, you can now buy a device that tracks your water use in real time for just $24, a steep discount, Alexandra E. Petri writes. And if you’re looking for additional relief from high water bills, tough luck — CalMatters reporter Rachel Becker notes on Twitter that Gov. Gavin Newsom “vetoed a bill to establish a water rate assistance program, citing no identified funding source.”

The challenges of transitioning from fossil fuels to clean energy could help determine which party controls Congress the next two years. That’s especially true in a crucial House of Representatives district straddling Orange and San Diego counties, where high gas prices, last year’s oil spill and California’s electric-vehicle ambitions have become key issues as Republican Brian Maryott tries to unseat Democratic incumbent Mike Levin, The Times’ Seema Mehta reports. If you hadn’t noticed, gas prices are absurd in California right now, hitting a record $6.49 a gallon in Los Angeles this week as oil refinery outages reduced supply, Grace Toohey writes. And speaking of the Orange County oil spill, the undersea pipeline at fault could be operational again by early next year, Christopher Goffard reports.

Will scientists be able to save California’s forests from going up in smoke? They’ve got the tools, but time is short, and it will cost a lot of money. That’s the takeaway from this illuminating story by my colleague Alex Wigglesworth, with graphics and illustrations by Paul Duginksi and Szu Yu Chen, showing how prescribed burns and careful thinning can create healthier forests more resilient to wildfire, drought and bark beetle infestation. Even in a best-case scenario, though, the Golden State’s beloved forests will see dramatic change as the planet continues to heat up. The Times’ Doug Smith describes some of those changes in a beautiful first-person piece about his lifelong relationship with the Sierra Nevada. “That’s the thing about the Sierra — and perhaps about getting older. Things evolve, sometimes deteriorate. But some things won’t change in my lifetime and many lifetimes ahead, and there’s comfort in that,” he writes.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

The small Navajo Nation community of Westwater is finally getting electricity after decades of waiting — and running water could be next, in part due to millions of dollars in federal COVID-19 relief funds. Details here from Shannon Mullane at the Colorado Sun. Yes, it’s probably pretty hard for most of us to imagine living without power in the United States, but it’s a real problem for certain low-income communities, especially communities of color — even here in Los Angeles, where some activists say the Department of Water and Power should permanently end utility shutoffs for residents who can’t afford to pay their bills, as Erin Stone reports for LAist. On the other end of the economic spectrum, people living in mega-mansions can run up monthly electric bills into the tens of thousands of dollars. My colleague Jack Flemming explains how that’s even possible.

Pacific Gas & Electric says it’s selling a 49.9% stake in its power plants (except the Diablo Canyon nuclear plant) to help finance wildfire safety and clean energy projects. Here’s the story from Reuters on PG&E’s latest shift in strategy, as the beleaguered company tries to stop sparking deadly fires and invest in the power-grid upgrades California will need to replace gasoline-fueled cars with electric vehicles. In other PG&E news, former executives agreed to a $117-million settlement over deadly fires in 2017 and 2018, after being sued by a victim trust that claimed the blazes were a direct result of the former executives’ actions, Nathan Solis reports.

“As battery storage matures in real time, its social license depends on its ability to fail without hurting people.” So writes Canary Media’s Julian Spector, in a fascinating story about what Tesla and other energy storage companies are doing to stop the battery fires that have plagued the nation’s largest complex of lithium-ion batteries, along California’s Central Coast at Moss Landing. The most recent fire was just two weeks ago. So far, the fires haven’t been especially dangerous — unlike a 2019 incident in Arizona that sent four emergency responders to the hospital — but they’re a serious growing pain the energy industry will need to figure out.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

Gov. Gavin Newsom has broken with the California Democratic Party and many environmentalists to oppose Proposition 30, which would raise taxes on the wealthy to fund electric car chargers and wildfire resilience. L.A. Times columnist George Skelton applauded Newsom’s stance, writing that Proposition 30 “would embroider California’s reputation as a far-left state drawn to tax hikes rather than setting spending priorities.” (A new poll co-sponsored by The Times shows 49% support for the ballot measure, with 37% opposed and 14% undecided.) Newsom is also calling on lawmakers to impose a “windfall tax” on the oil industry, blaming the recent rise in gas prices in part on “oil company extortion,” Jonah Valdez reports. At the same time, the governor vetoed a bill that would have aligned state transportation funding with climate change goals — meaning, as my colleague Liam Dillon notes on Twitter, that “all the major legislation that aimed to limit freeway expansion in California this year failed.”

In her first day on the bench, Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson led the questioning in a consequential case to determine the scope of the Clean Water Act. The justices are expected to rule on whether the law protects thousands of intermittent streams, arroyos, wetlands, marshes and other waterways, with huge implications for Western water supplies and ecosystems, Jonathan Thompson writes for High Country News. If the high court limits the Clean Water Act’s scope, up to 66% of California’s streams and rivers — and 94% of Arizona’s — could be removed from federal oversight, Thompson notes. The Times’ David G. Savage watched the arguments before the conservative-leaning court and writes that it’s unclear how the justices will rule.

More than 10% of the Colorado River’s water is lost to evaporation, seepage and other factors each year — but due to a “historical quirk,” the Lower Basin states of California, Arizona and Nevada don’t have to count evaporative losses against their water allocations. With the Colorado River in crisis, the federal government is finally telling those states to prepare for significant cuts to account for evaporation, KUNC’s Luke Runyon reports. Elsewhere on the Colorado, California’s independent Salton Sea panel finally has recommendations for how to support the dying lake. The panel advised against importing water from Mexico’s Sea of Cortez but supported the idea of building a large desalination plant to filter the increasingly salty lake water. More details here from the The Times’ Ian James.

AROUND THE WEST

The world’s most promising research into “enhanced” geothermal energy is happening outside Milford, Utah. The Salt Lake Tribune’s Tim Fitzpatrick wrote about the University of Utah’s federally funded FORGE lab, which is trying to make round-the-clock, climate-friendly geothermal power from deep beneath the ground easier to access in more places by adapting fracking technology from the oil and gas industry. Geothermal energy is already produced in large quantities at California’s Salton Sea, where companies are now trying to produce lithium for energy storage systems as well, as I’ve reported previously. But at least one lithium effort hit a roadblock earlier this year, when the federal government rescinded a grant to Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Energy, as Reuters’ Ernest Scheyder reports. The hot, corrosive Salton Sea geothermal brine continues to be hellishly difficult for companies to handle.

A New Mexico coal plant that once powered Disneyland closed this week, bringing the American West one step closer to ending its reliance on the dirtiest fossil fuel. New Mexico Political Report’s Hannah Grover talked with longtime employees of San Juan Generating Station about what they’ll do next, and the difficulty of finding jobs as steady or as high-paying as the ones they’ve worked for decades. She also explored the long history of clean air activists trying to block the plant’s construction and ultimately get it shut down. For a broader rundown of Western coal plant closures — and a list of which plants still don’t have retirement dates — see my story from earlier this year.

The first-ever video has been captured of a mountain lion preying on a wild burro in Death Valley National Park. My colleague Grace Toohey has the story, including some nuanced discussion of the role invasive burros play in the park.

ONE MORE THING

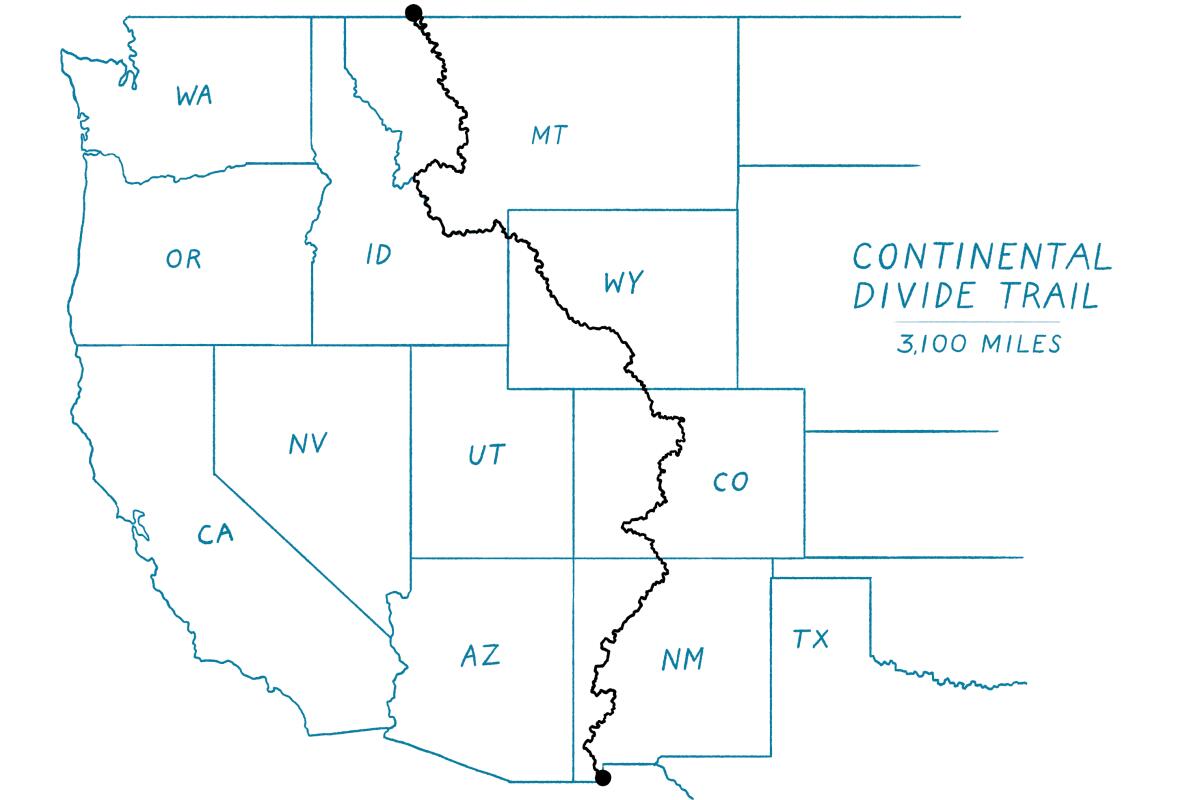

Journalists typically aren’t supposed to take public stances on legislation and policy proposals. But with the 50th anniversary of the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail coming up, there’s bipartisan legislation in Congress that would direct federal agencies to actually finish building it. As an avid hiker who’s spent a bunch of time reporting along the Continental Divide, this one sounds pretty good to me.

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, or previous ones, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues. For more climate and environment news, follow me on Twitter @Sammy_Roth.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.