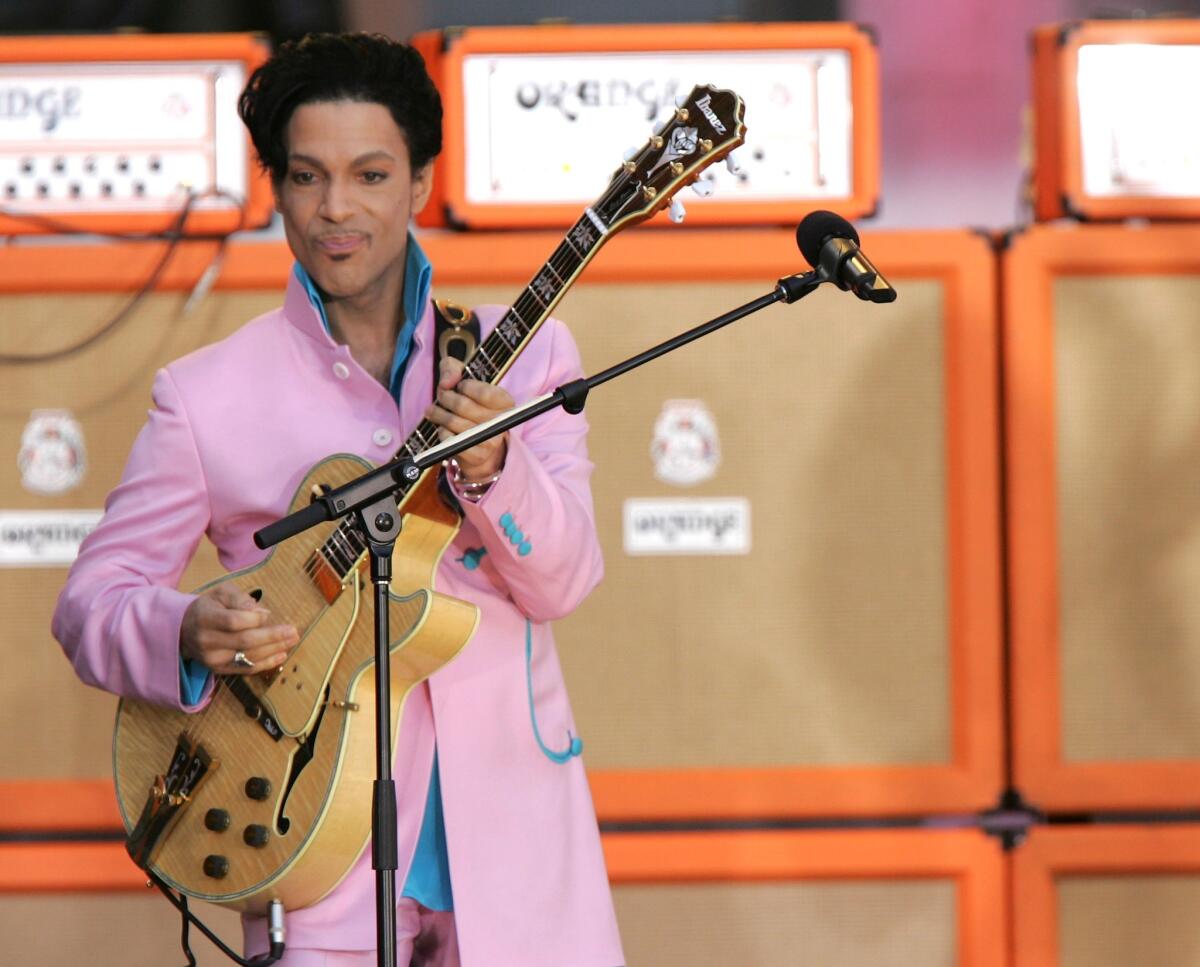

What today’s artists learned from Prince’s approach to the industry

- Share via

Prince’s relationship with the music industry can be summed up in a quote he gave to Rolling Stone in 1996: “If you don’t own your masters, your master owns you.”

It’s a volatile remark about self-determination in the music business (though not Prince’s most barbed -- he once protested his contract at Warner Music by writing “Slave” on his face). But it’s also just good advice that any young musician should pay heed to, especially in an Internet-decimated environment for making money on recordings.

Prince was a streaming skeptic before it was fashionable, yet also a born futurist, a pioneer of giving away free music and creating new distribution systems under his purview. He almost never settled for less than total control of his music in the marketplace, and when he didn’t get it he fought risky public battles for it. Artists today owe him a profound debt for that.

In the current climate, Prince’s near-wholesale shunning of streaming services (and his camp’s itchy takedown-notice trigger finger for unauthorized bootlegs) seems almost soothsaying. As anyone who tried to memorialize him on the Internet on Thursday discovered, it’s nearly impossible to find embeddable, authorized Prince songs on most popular services like Spotify and YouTube.

This was by design. Prince famously declared in 2010 that “the Internet is over” as a hope for revenue-generation in music. “Tell me a musician who’s got rich off digital sales. Apple’s doing pretty good though, right?”

Of course, he eventually signed onto Tidal, perhaps out of faith that its big coterie of musician-owners represented a counterweight to larger tech and music biz demands and paltry royalties. The service’s fortunes have ebbed and flowed based on which friends of Jay-Z have released new albums, but if 2016 has proved anything, it’s that Tidal’s catalog of exclusives suddenly looks ever-more essential.

Without Prince’s precedent-setting skepticism, artists like Taylor Swift and Adele might have been less inclined to take stands against Spotify, whom they saw as cannibalizing sales and paid streams with their ad-supported service.

Other artists like Justin Bieber and Kygo have, of course, used free streaming to huge effect in furthering their careers (and even Prince eventually uploaded one-off singles to Spotify and YouTube). But Prince at least helped establish an option of saying no.

Prince had been down that road before when the stakes were maybe even higher. He saw his fight with Warner Music in profoundly racialized terms, a grim fact of the music business that stretches back as long as white executives have recorded black artists. He wasn’t just trying to negotiate a better contract -- he framed the whole discussion in terms of freedom and his own artistic agency.

In the early ‘90s, he changed his name to an androgynous symbol in order to signal a fundamental severance from an identity he saw as a wholly owned commodity of Warner. Anyone following the “Free Kesha” fight will recognize some similar undertones.

When he finally extricated himself from Warner and established NPG Records (a replacement for his Paisley Park imprint at Warner), he seemed to relish rubbing it in their faces, signing one-off album deals with many of its biggest rivals (EMI, Arista, Columbia, Universal), though he did eventually return to Warner in 2014).

Even at his new labels, he couldn’t resist undermining them. His most famous contrarian-release stunt came when he packaged 2007’s “Planet Earth” in 2 million copies of the British newspaper Mail On Sunday.

BMG yanked the album from its British release, but the gesture was clear -- Prince would release music how and when he wanted to, because when he gave it away it was on his terms. Bands like Radiohead and Nine Inch Nails got the early credit for pioneering album giveaways in the post-mp3 era, but Prince’s name belongs on that ledger as well.

This track record makes it seem like Prince was a resistance fighter against capitalism and modernity, but he was far from it. He was one of the first acts to allow fans to buy albums right from the source, via the Internet, all the way back in 1997 for “Crystal Ball.” His NPG music club (and later LotusFlow3r) was one of the first subscription-based digital music services, bundling his records and concert ticket sales into a catch-all Prince portal.

It’s impractical to imagine every artist maintaining a site like that, but for one with a super-devoted following, massive output of material and a consistent live draw, it made a lot of sense, and proved the concept that musicians can set the terms of how they engage their audience (and customers) online.

Not all of it worked. Prince’s output never dropped off, but the individual impact of his late-career, alternative-model records never matched his Warner-era monuments. Sometime his catalog-policing caused unnecessary collateral damage, as in the famous Lenz vs. Universal case, in which a mother was given a takedown notice for a video of her baby dancing to “Let’s Go Crazy.”

However, what Prince was fighting for, most crucially, was the right to own the mechanisms for how his music entered the world.

“People think I’m a crazy fool for writing ‘slave’ on my face,” he said in that same 1996 interview. “But if I can’t do what I want to do, what am I? When you stop a man from dreaming, he becomes a slave.”

Follow @AugustBrown for breaking music news.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.