Artist Julian Schnabel explores Van Gogh on film and in a new museum show

- Share via

“I think you need to walk around the show and just see how you feel,” says artist and filmmaker Julian Schnabel as he explains his new exhibition, “Orsay Through the Eyes of Julian Schnabel,” which opened Oct. 10 at the Musée D’Orsay in Paris. It’s the 31-year-old museum’s first show by a contemporary artist, and presents an unusual perspective on notable artists like Vincent Van Gogh and Édouard Manet. Schnabel is all about searching for feelings in the moment, particularly in his upcoming film “At Eternity’s Gate,” which takes an impressionistic look at Van Gogh’s tumultuous final years.

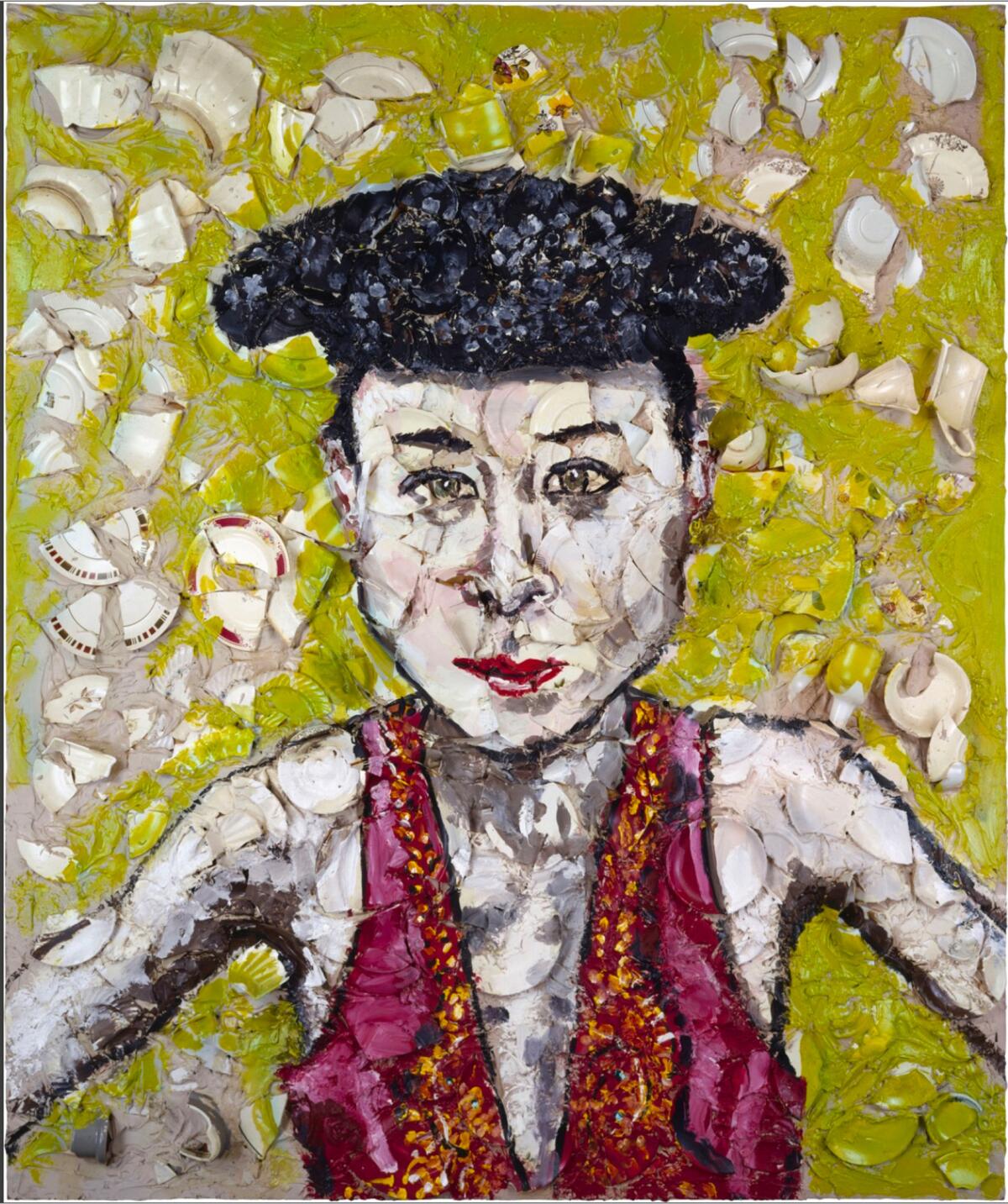

Housed in two rooms on the second floor of the museum, the exhibition creates a visual dialogue between classic and contemporary. In the first room, which has vaulted ceilings that evoke a cathedral, the paintings are hung at various levels, some in the eye line of the viewer and some towering from above. The vertical nature of the installation adds to the church-like atmosphere, offering an almost fresco-like aesthetic that amplifies the intensity of the works. The focal point is Van Gogh’s “Self-Portrait,” painted in 1889, the year before his death. The piece is one of the museum’s most popular pieces and Schnabel has juxtaposed it on the same wall with his 1987 work “Tina in a Matador Hat,” which was created from paint and broken plates.

“If you look at the painting and you look at how all these marks are like waves of energy as they go around his shirt, and the way all the colors seems almost monochromatic with different versions of blue and green, it’s reverberating,” Schnabel says, leaning in toward the Van Gogh. “It’s very interesting because what he did is he painted and showed the autonomy of all the marks. If you get up close you can see each mark of the painting and when you get back, with distance, the painting forms a face. His approach was really radical at the time and people couldn’t really understand what he was doing. If you look at that painting and this painting and you see the way the plates are vibrating around [Tina] as if energy, as if they were being broken or exploding, these paintings speak to each other.”

Why Van Gogh now? Schnabel, who is being documented continuously by Benoît Delhomme, the French cinematographer who shot “At Eternity’s Gate” and who now follows the director with his camera through the museum’s rooms during this interview, wanted to prove that not everything had been said about the Dutch artist, played in the film by Willem Dafoe.

“Everybody thinks they know everything about him so it’s impossible to make a movie about him — I don’t like any of the movies ever made about him,” says the Oscar-nominated director, who previously has made films about painter Jean-Michel Basquiat, poet Reinaldo Arenas (“Before Night Falls”) and Elle magazine editor Jean-Dominique Bauby, whose stroke resulted in the locked-in syndrome so vividly enacted by Mathieu Amalric in “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly.”

“I don’t like any of the movies ever made about him. It’s the same reason as why would I even make an attempt to show things with my paintings or teach anybody anything? Why would I even think I could do that? Who knows what that impulse is to want to show something? But Van Gogh says in the movie that he’d like to give his human brothers hope and consolation.”

Van Gogh is not necessarily the primary subject of the exhibition, although he resonates throughout, as does Paul Gauguin, portrayed in the film by Oscar Isaac. Schnabel created the exhibition in collaboration with Donatien Grau, project leader for the president of the Musées d'Orsay et de l'Orangerie, as well as Louise Kugelberg, who wrote and edited the movie alongside Schnabel. “We got this idea that maybe it would be interesting if I showed the way I see the museum,” Schnabel says. “Museums are not mausoleums. They think of different ways of creating perspectives so people can look at paintings in a fresh way. And, in fact, the museum is very much alive.”

The artist was given liberty to select works from the museum’s permanent collection, and by presenting these pieces in tandem Schnabel offers a new lens through which to view the museum. “What happens is that most people just look at the images in paintings — they don’t look at how they made the painting,” the director notes. “This show is about how to paint and people’s approach to painting.”

In one corner, Schnabel has paired Claude Monet’s “The Turkeys,” a lesser known work from 1877 that reveals its subjects through large dabs of paint, with his own “Rose Painting (Near Van Gogh’s Grave) XVII,” another work made with broken plates. While most of Schnabel’s paintings are several decades old, this one was painted last year and has never previously been displayed in a gallery. “When you get up close it looks like a mess,” he notes of his own work. “And when you get up close to this one,” he says of Monet’s painting, “it doesn’t look like a turkey; it looks like some paint. The point is you get back and you can see it. It’s about perception [and] about spatial color.”

Gauguin’s “Les Alyscamps” and Manet’s “Lady With Fans (Portrait of Nina De Callais)” bookend Schnabel’s “Portrait of Tatiana Lisovskaia as the Duquesa de Alba II,” which he finger-painted in 2014. These combinations create moments throughout the two galleries, which is exactly what Schnabel hopes to do with his art.

“The fact is that there’s no difference between my attitude towards making a painting and making a movie,” he says. “You get to look at the paintings and see how you feel, or you get to look at the accumulative scenes of a movie and then you walk out of a movie and see how you feel. When I wrote the structure of this movie it came from me looking at some paintings with [co-screenwriter] Jean-Claude Carrière thinking, ‘Let’s walk up to each painting and get a feeling about it.’ It wasn’t as didactic as that, but you walk up to each painting and get a feeling. At the end you have 15 feelings and you walk out.”

Schnabel painted many of the Van Gogh works that appear in “At Eternity’s Gate” (Dafoe also painted on-screen), and the director centers much of the film, which opens Nov. 16, on the idea that Van Gogh worked very quickly, wanting his paintings to be articulated in one gesture.

“What the show is about is looking at something,” Schnabel says. “[In the film] I wanted to show that when you get up close to those images they just look like paint. I was showing a way of how to look at Van Gogh’s paintings.”

And does Schnabel himself work that quickly? He shrugs. “Do I paint in one clear gesture?” the director asks. “You can see it.” He nods around the gallery and replies, “You need to look at the paintings.”

“Orsay Through the Eyes of Julian Schnabel”

Where: Musée d'Orsay, 1, Rue de la Légion d'Honneur, Paris

When: Through Jan. 6. Closed Mondays.

Info: musee-orsay.fr

“At Eternity’s Gate”

Rated: PG-13

Running time: 1 hour, 50 minutes

Opens: Nov. 16

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.