Review: The ‘Maverick Modernist’ you don’t know but should: Peter Krasnow at the Laguna Art Museum

- Share via

In 1929, photographer Edward Weston made a portrait of his friend Peter Krasnow, 43, a painter and sculptor whose studio in Atwater Village was not far from Weston’s own in the Glendale area then known as Tropico.

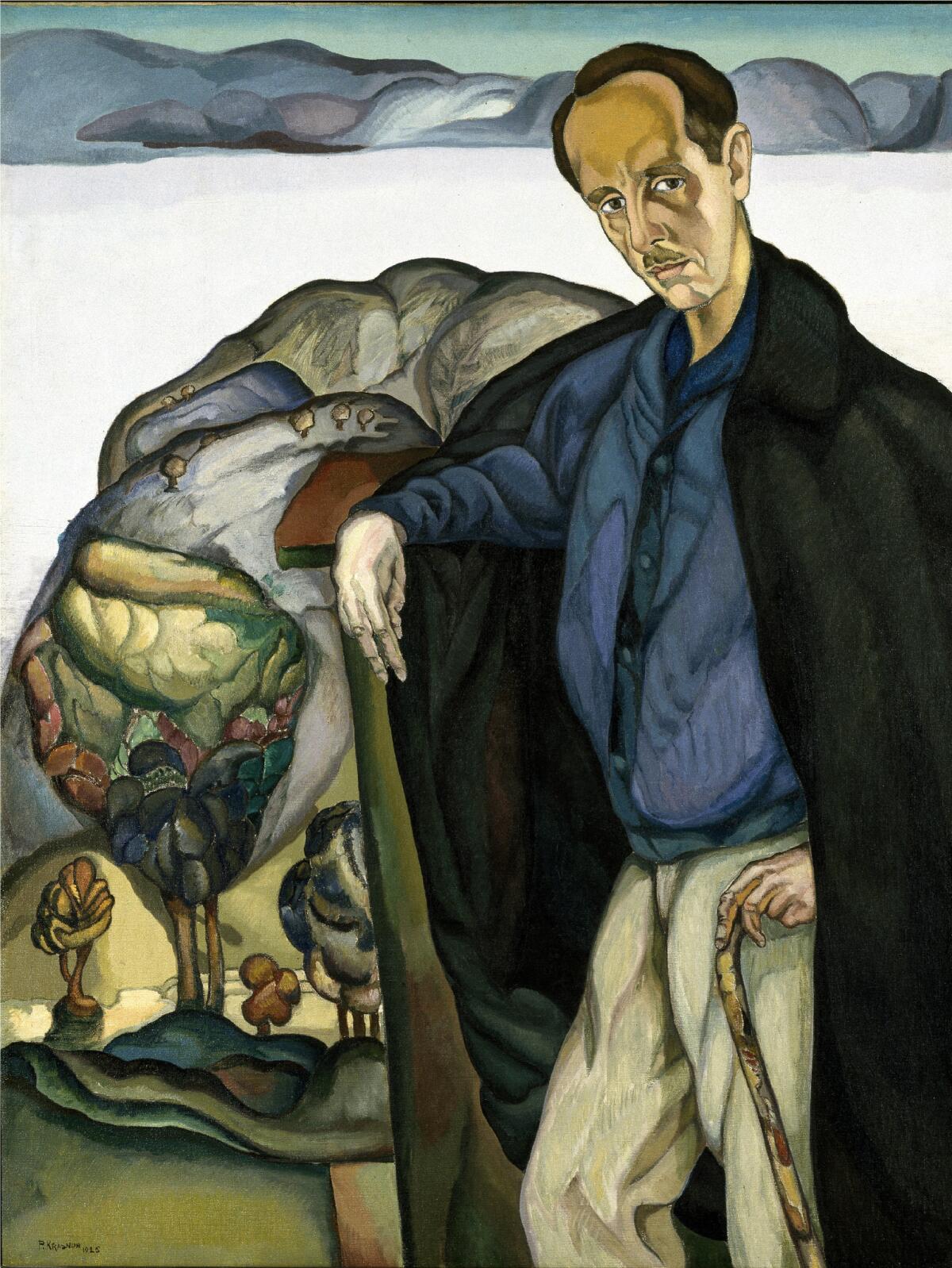

Krasnow had painted his portrait a few years earlier, portraying the camera artist as a kind of techno-wizard shrouded in a dramatic cape, positioned before a flat, stylized modern landscape in the style of Weston’s close and influential friend, painter Henrietta Shore. Weston returned the favor: His picture goes to the heart of Krasnow’s thinking as an artist.

The portrait hangs at the entry to “Peter Krasnow: Maverick Modernist,” a modest yet thoroughly engaging retrospective exhibition at the Laguna Art Museum. Krasnow, seated on a low rock, is set against a hill, the absence of a horizon flattening the pictorial perspective.

Dressed in what appears to be an equestrian outfit complete with buckled leather shin guards, Krasnow’s figure fills the frame. He’s a man of action now restrained, resting his head in his right hand, elbow balanced on his knee.

Krasnow’s pose is world-weary, melancholic. (Does the 1929 date, shuddering harbinger of boom-and-bust economic collapse, have anything to do with it?) Yet the artist’s prominently positioned hands, marked by gracefully elongated fingers, speak a kind of pictorial sign language.

One hand reaches across to steady the other, which is raised to his brow to shield one eye in shadowed darkness while letting the other gaze out into the world. Weston shows a bleak Krasnow looking simultaneously outward and inward, one eye cast on the visible world and the other on his unseen inner being. The exquisite photograph evokes a Modernist impulse, which animated his friend’s art.

“Peter Krasnow: Maverick Modernist” is the second show this season to unfold the career of a significant Los Angeles artist who is underknown. (The other was February’s “Helen Lundeberg: A Retrospective.”) Organized by guest curator Michael Duncan and accompanied by a fine catalog with essays by Duncan and art historian Susan Ehrlich, it represents the continuing relevance of a laudable mission for the small seaside museum.

And Laguna is singularly equipped for the Krasnow task. The artist was notoriously hesitant to sell his work, preferring to remain aloof from art’s commercial hurly-burly. In 2000, his estate made a bequest to LAM of 147 paintings, 57 sculptures and around 600 works on paper.

The gift included an undisclosed sum of money to prepare an exhibition and catalog. The current show, which also draws on other Krasnow works from the LAM collection as well as loans, has finally accomplished the task.

Underknown barely begins to describe Krasnow.

Since his death at 92 in 1979, a few years after retrospectives at the Municipal Art Gallery in Barnsdall Park and the Skirball Museum, his work has been largely invisible, save for periodic shows at the stalwart Tobey C. Moss Gallery in Hollywood. (Most were in the 1980s.) As with his art market aversion, that’s partly the way Krasnow wanted it. Time and again throughout his life, he turned away whenever acclaim or success came to call.

Most dramatically, following a very well received 1931 museum exhibition at San Francisco’s Palace of the Legion of Honor, Krasnow and his wife, Rose, promptly closed their L.A. house and decamped to a small farming village in rural France, where they lived on a shoestring for the next three years. It’s as if he was certain that no one would be able to find him there.

The Laguna show is loosely organized according to these breaks in the artist’s trajectory, breaks that were typically accompanied by a shift in his work. Returning from France to Los Angeles, for instance, Krasnow mostly stopped painting to focus on carving totemic wooden sculptures.

Their abstract shape is partly dictated by the tree’s natural growth pattern and partly by the artist’s piecing together of multiple blocks of wood. The formal dialogue between nature and culture passed from his paintings, such as the Weston portrait, into sculptures that bear no visual resemblance.

The sculptures are sometimes likened to Brancusi’s work. For both artists, the sculpture and its base are inseparable, their considered forms physically connecting art to the world. They perform a precarious balancing act between symbolic figurative associations and abstraction derived from the inherent qualities of materials in space.

But Krasnow’s sculptures are more like vertical puzzles. Individual sculptural units are carefully carved, then stacked and locked together as they reach upward from the ground. A distinctly spiritual dimension marks the union of material naturalism and figurative allusion.

A shift in his art came again when World War II darkened the globe — and it includes a surprise.

The new work, which evolved over the next 30 years, is driven by fierce color. Krasnow returned to painting, feeling he had done all he could with carved wood sculpture. His bright pastels and vivid candy hues — pink, turquoise, violet, baby blue, lime — are finally unlike anything in art before.

The new paintings didn’t continue the focused portraits or bleak Social Realist subjects of working class and immigrant strife that he had made before. Instead, patterned abstraction was the new motif — often geometric, sometimes derived from symbolic sources such as the Hebrew alphabet and occasionally alluding to nature.

Like the organic forms in Krasnow’s sculptures, the abstract shapes in his paintings lock together in a unified, balanced whole. And pure color — straight from the tube, unmixed and unblended — is everywhere, creating exuberant, even celebratory rhythms.

Given the trauma of the war years, the eruption of such colorful exuberance seems counterintuitive. Which may be the point: In the face of death, rejoice in life.

The abstractions recall elements of Kandinsky’s late paintings of the 1930s and early 1940s. Krasnow would have known the work through his friendship with Galka Scheyer, the émigré German American art dealer who promoted Kandinsky’s work in Los Angeles. It’s as if he picked up a spiritual thread and wove it through blazing California light.

Yet perhaps the most direct connection is with Krasnow’s own early work. Born and raised in small-town Ukraine, he fled the murderous pogroms that flourished in the years around the Russian Revolution, landing in America in 1907. (His birth name was Feivish Reisberg, randomly changed by the immigration office.) He bounced around from Boston to Chicago to New York, before heading to L.A.

In the show’s first room, a formal 1919 wedding portrait sets a festively attired woman before a richly patterned Eastern European or Central Asian textile, perhaps a hand-embroidered suzani. Imagine the picture without the figure, just the patterned network of circles, squares and organic shapes of the cloth. Krasnow’s vibrant abstract paintings from the final decades of his life offer up those traditional patterns of celebratory ritual — revised, remade and reinvented in a thoroughly modern idiom.

------------

“Peter Krasnow: Maverick Modernist”

Where: Laguna Art Museum, 307 Cliff Drive, Laguna Beach

When: Through Sept. 25. Closed Wednesdays.

Info: (949) 494-8971, www.lagunaartmuseum.org

Twitter: @KnightLAT

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.