Critic’s Notebook: Hollywood & Highland censors sculpture in response to Weinstein scandal

- Share via

In the tumultuous aftermath of the

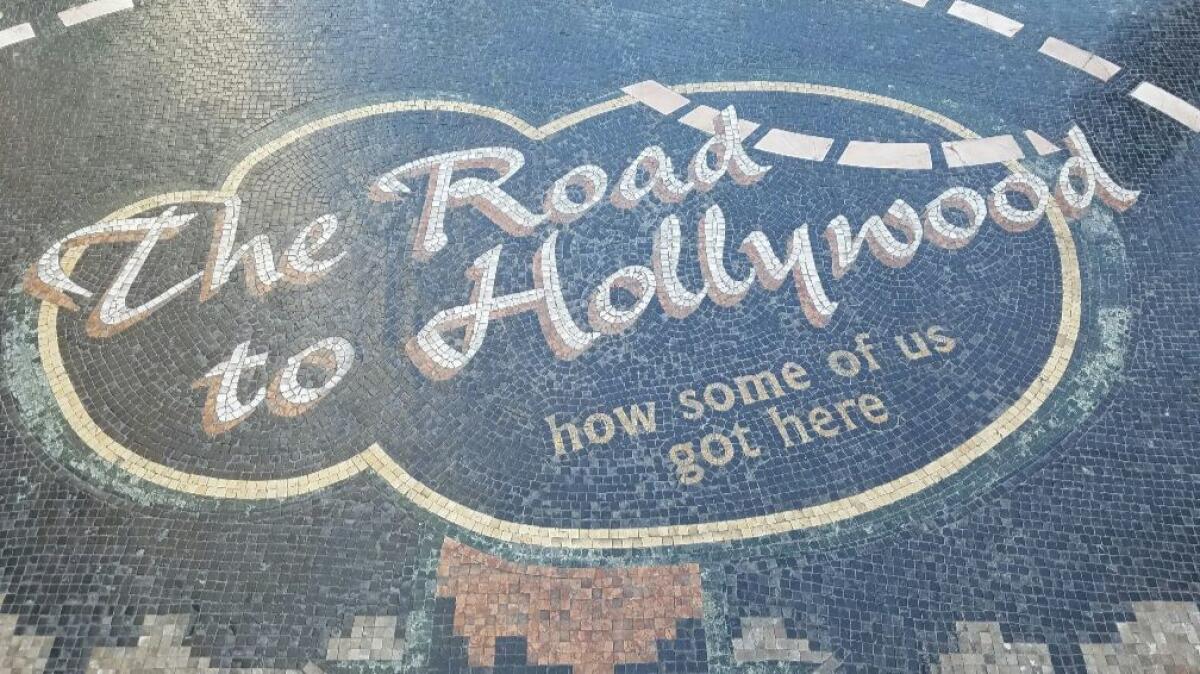

The piece is a fiberglass sculpture of a daybed, the pinnacle of “The Road to Hollywood,” a large and complex installation by artist Erika Rothenberg. It was removed Thursday from its perch at Hollywood & Highland, the shopping mall adjacent to the theater where the Academy Awards are handed out.

In the eyes of some, an innocuous daybed became a casting couch.

The removal follows accusations against Weinstein of sexual harassment and assault of women during his more than 30 years as a producer in Hollywood. In one week, the Weinstein scandal converted a benign scultpure into a radioactive symbol.

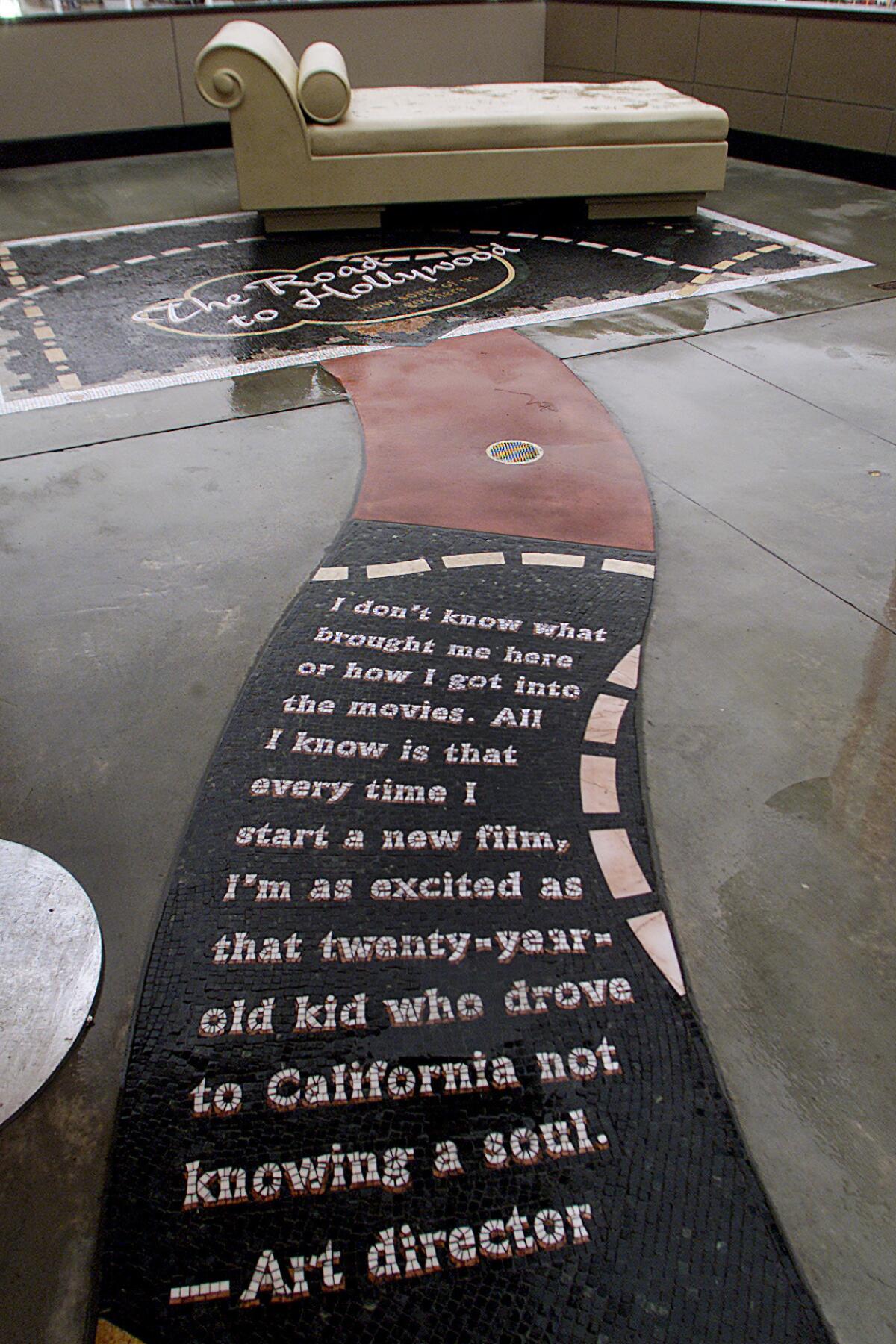

The massive fiberglass daybed was intended as a place for tourists from around the world to stretch out and ponder the artist’s always poignant, sometimes comic, finally sobering take on the Hollywood dream. Fifty narrative mosaic-texts are embedded in a “red carpet” in the pavement that begins on Hollywood Boulevard, climbs the stairs, and winds through the mall. Each mosaic tells a succinct story of why an anonymous actor, studio hand or other worker in the industry chose to leave their home and head west.

The mosaics record their dreams. Plainly, none dreamed of being raped.

The concrete path, which morphs into film stock at the top of the stairs, passes through the mall’s Gates of Babylon and out to a rear terrace, backed by sweeping views to the Hollywood sign in the distant hills. There stood the daybed, site of thousands of tourists’ photographs snapped over the last 16 years.

On Thursday, Rothenberg’s daybed sculpture was dragged into an adjacent hallway (it’s heavy, originally requiring a crane to install), deposited next to a soda machine and wrapped in a blue tarp.

The legality of the censorship is questionable. The Visual Artists Rights Act of 1990, although seldom invoked, is designed to prevent “any intentional distortion, mutilation or other modification” of a work of art. The federal law followed passage of the similar 1979 California Art Preservation Act.

Seven years ago, Los Angeles painter Kent Twitchell won a $1.1-million settlement from the federal government and the YWCA of Greater Los Angeles, among other defendants, under VARA. His 70-foot mural-portrait of fellow artist Ed Ruscha, which adorned the side of a downtown building, had been painted over.

In response to an inquiry, Hollywood & Highland management issued a statement saying that “in light of current events we have deemed this component of ‘The Road to Hollywood’ to be insensitive and it has been removed from public display.”

“I get it,” said Rothenberg, reached by telephone, of the false claim newly pinned on her sculpture. Rothenberg was not consulted by the mall’s management company that censored the piece, and she is unhappy about the decision. But she knows that context, which always confers meaning on art, is malleable and a public context can change.

“Abuse by the powerful is real,” she said. “They’re the enemy. And not just in Hollywood.”

One might say the same about the abuse of censorship. The sculpture was completed in 2001, commissioned through the city’s Community Redevelopment Agency, which no longer exists, for the original owners of the shopping complex. Hollywood & Highland was designed to help jump start redevelopment after decades of neighborhood decline.

Today, Hollywood is booming, and it attracts a steady stream of visitors. A nervous corporation, worried about its business, is no surprise.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

More unexpected, and in certain respects more disappointing, is the applause that censorship has garnered in some corners of social media and the internet. It’s a testament to how our new digital mob-ocracy operates.

TripSavvy, an internet travel guide, blithely features a photograph of the daybed under the inflammatory headline “Casting Couch.” A reader of Shakesville, a self-described progressive feminist blog, called attention to the newly dubbed "casting couch statue in Hollywood,” accompanied by a claim that at least one local tour guide makes “smirking, smarmy comments” about the sculpture to customers.

The blogger, tagging the blog post under “rape culture,” demanded “Get rid of it. Now,” after telephoning Hollywood & Highland management — twice.

On Facebook, an urban fan site called Hidden Los Angeles linked to the misguided Shakesville post, prompting a short flurry of disagreements over the meaning of “The Road to Hollywood” and whether the daybed should stay. On Twitter, a local filmmaker entered the fray, making a farfetched comparison between the daybed and a Confederate Civil War monument, as if both glorify criminals.

In reality, so-called Confederate monuments are Jim Crow monuments, erected 50 and 100 years after the Civil War to intimidate African Americans while giving comfort and civic support to 20th century white supremacists. That’s why they should be taken down and delivered into history museums.

Also in reality, “The Road to Hollywood” is a narrative work of art that compiles actual stories of men and women drawn to Southern California from across the country throughout the 20th century by the siren call of a chance for a different life. It tells myriad stories of their dreams. The title, embedded not once but twice in the pavement, even explains: “How some of us got here.”

FULL COVERAGE: The Harvey Weinstein scandal »

To accept the mistaken claim about the daybed is to accept the preposterous idea that some made the journey in order to suffer the nightmare of sex abuse. The sculpture of a daybed by Rothenberg — herself a well known and committed feminist artist — was not made to represent a casting couch. The daybed is a place to daydream.

That the Hollywood context has dramatically shifted in recent days is akin to the sordid recent events in Charlottesville, Va., which lit the fuse under a long-simmering reconsideration of Jim Crow monuments. The difference, of course, is that the latter exposed what the sculptures actually are, while the other has shined a spotlight on a pervasive social calamity that exists not only in Hollywood but far beyond the entertainment industry.

The Weinstein disgrace arrives in the wake of the Bill Cosby scandal. It is further magnified by its apparent mirror reflection of the words, “when you’re a star, [women] let you do it. You can do anything,” uttered by a celebrity game show host who now occupies the White House after garnering 62,984,825 votes from fellow Americans, male and female, apparently unconcerned with such malignancy.

The iconoclastic applause for censorship is also disturbing. The awful distress that fuels it, as Rothenberg fully appreciates, is understandable. But censorship creates a false illusion of power exerted in the face of seemingly intractable powerlessness. The swift removal of a benign sculpture, which ruins a great work of art, has the ironic effect of putting serious protesters of systemic rape culture on the same side as corporate managers most concerned with protecting the bottom line.

The final mosaic text in “The Road to Hollywood” installation, just before a visitor arrives at the big daybed, is written in the knowing voice of an art director. “I don’t know what brought me here or how I got into the movies,” it says. “All I know is that every time I start a new film, I’m as excited as the 20-year-old kid who drove to California not knowing a soul.”

Not knowing a soul. The observation, emblematic of the artist’s acute rhetorical gifts, can be read two ways, the second one “Day of the Locust” and Nathanael West-style. Rothenberg’s great, prescient work of art nails the soulless Hollywood of Weinstein, Cosby, Trump and scores of those who came before. Its tragic censorship must not stand.

More Times arts news and reviews at latimes.com/arts.

Twitter: @KnightLAT

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.