Commentary: The Arts District’s first-ever skyscrapers would be unlike any other development in L.A.

- Share via

To paraphrase Ronald Reagan by way of Basel, Switzerland, it’s morning again in the Arts District.

At least that’s the upbeat sales pitch suggested by the name of a massive mixed-use development proposed for downtown L.A.’s booming Arts District by the Swiss architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron.

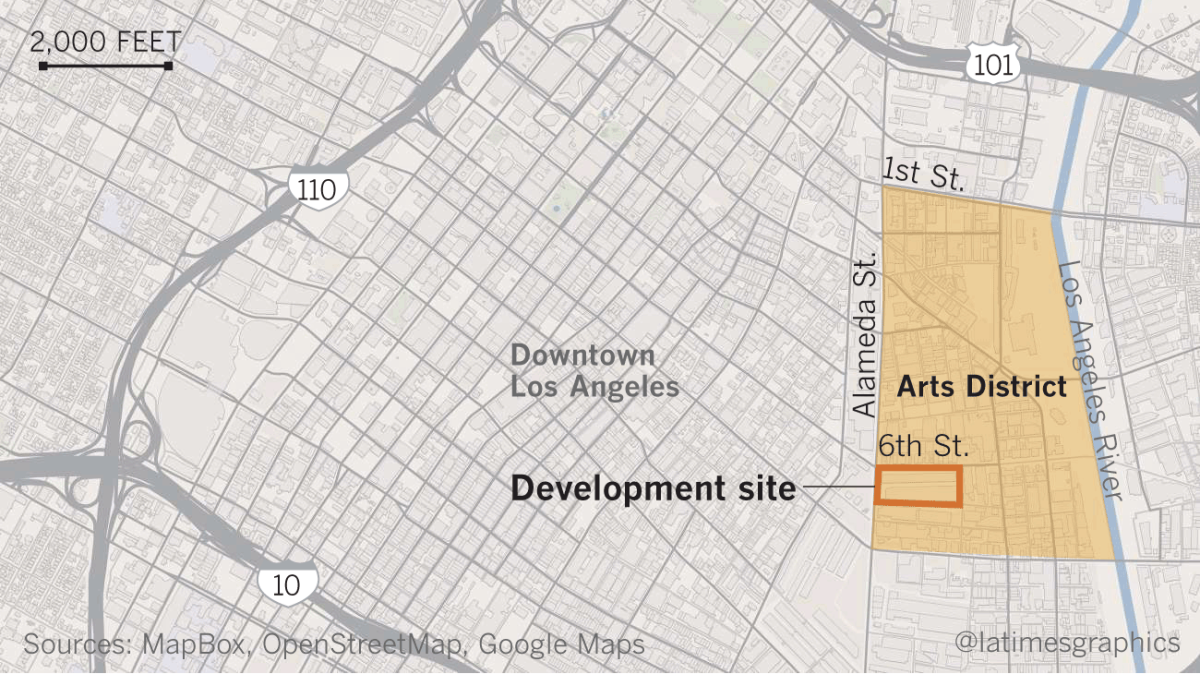

Called 6AM — for its location along 6th Street between Alameda and Mill streets — the project includes 1.96 million square feet of residential space as well as shops, offices, a pair of hotels, room for a charter school and parking, most of it underground, for more than 3,400 cars.

Produced with the Irvine-based developer SunCal and covering 14.5 acres, the complex would be crowned with a pair of 58-story towers along Alameda. Each topping 700 feet, these would be the first skyscrapers in the largely low-rise Arts District.

Given debates about the pace and scale of development now roiling Los Angeles in general and the Arts District in particular, the proposal, which De Meuron and SunCal chief executive Bruce Elieff pitched Friday to Deputy Mayor Raymond Chan and other city officials in advance of filing preliminary plans next week, is likely to be a lightning rod for controversy. In height as well as bulk it would dwarf its neighbors, and the project would require a zone change and general-plan amendment from the city.

The developers certainly seem to be anticipating some blowback. Renderings released to The Times this week show an aerial view of the towers as almost ghostly forms and seen from only one angle: looking northwest, allowing them to blend in with the Bunker Hill skyline. Glimpsed from any other direction they would stand out from the surrounding architecture in a much starker way.

Overall, the design is thoughtful in its response to its site — and more broadly in the way it adds to the conversation in Los Angeles about the role of vertical architecture. What’s more, there is no large architecture firm in the world doing work as consistently adventurous or deft as Herzog & de Meuron, whose American projects of note include the Perez Art Museum Miami, the De Young Museum in San Francisco and a forthcoming condo tower on Leonard Street in Manhattan.

Even the anti-development activists who see every tall building in Los Angeles as a giveaway to moneyed interests or a threat to the existing character of the city may find something to admire here.

We'd be wise to hold on to some skepticism, though. We’re seeing the design for 6AM at its earliest and most optimistic — in its rosy-fingered-dawn phase. It is now as much a master plan proposal as an architectural one. What it’ll look like in the harsh light of day, once it’s been through the full, punishing planning and construction process, is something else altogether.

Huge projects like these that fill every inch of an urban megablock — Frank Gehry’s serially delayed Grand Avenue design for Related Cos. also falls into this category — are tricky to humanize and enliven for even the most talented of architects.

The marriage between Herzog & de Meuron and SunCal, which mostly builds master-planned communities with names like Meadowlark Estates, the Orchards and Plum Canyon, is hardly a natural one. AC Martin, as 6AM’s executive architect, has had to play marriage counselor, filling a role that Gensler, which has since dropped out, took on in an earlier stage. For legal reasons Herzog & de Meuron’s official title on the project is “design consultant.”

The architects haven’t done themselves any favors by going public with a proposal that at this point is lopsided in its attention to detail, far more developed at street level than in its towers, which remain cipher-like. The proposal calls for stacked parking right along the sidewalk on Alameda, an oddly anti-urban gesture, though SunCal and Herzog & de Meuron insist that those spaces could be converted to shops, offices or lofts as demand for parking falls over time.

The most striking and unusual feature of the 6AM design is the stark contrast it sets up between its vertical and horizontal sections. There is no in between, no mid-rise portion or transitional gesture.

The towers, which the architects call “needles,” aim for transparency and even a kind of delicacy, setting themselves apart from the reflective glass boxes that with their thick torsos dominate Bunker Hill. They feature condominiums (likely to average in the neighborhood of $1,000 per square foot, or $1 million for a 1,000-square-foot unit) set into a concrete frame with deep, shade-giving overhangs, sizable terraces and wide bands of glass.

The low-rise section at their feet offers a crowded, bazaar-like maze of shops, restaurants, offices and apartments. It also would be framed largely in concrete, a refreshing departure from the typical mid-rise apartment blocks in Los Angeles, which are almost always built of wood and as a result severely limited in architectural personality.

This part of the design is a densely, carefully stacked architectural composition, with some echoes of Herzog & de Meuron’s 1111 Lincoln Road in Miami, a parking structure whose open frame is filled on several levels with shops.

A horizontal band runs along the length of the 6AM design at 40 feet above the sidewalk, matching the height of nearby buildings. Below this concrete line — which the architects describe as the “table” — are two or three levels of retail and cultural space, dubbed the “fabric,” thickly planted and laced with pedestrian corridors open to the public. (The landscape design is by Mia Lehrer + Associates.) Above the table are a series of “fingers” — bar buildings running north-south and holding apartments and creative office space.

The result would be unlike anything recently completed in Los Angeles — muscular, intricate and porous all at once — although the way the renderings of the project depict murals decorating the concrete suggest Herzog & de Meuron have spent some time looking at the nearby Hauser, Wirth & Schimmel gallery complex. There are also hints in the design of the towers of AC Martin’s 1965 Department of Water and Power building at the crest of Bunker Hill.

In urban terms, Herzog & de Meuron and SunCal play up the intersection of 6th and Alameda as a crossroads with growing significance. Alameda is a key north-south corridor, with the potential to be as important to the eastern side of downtown as Figueroa Street is to the west. It also marks the hard western edge of the Arts District.

Sixth Street, meanwhile, is poised to become a more prominent east-west axis once the new 6th Street Viaduct — a dramatic $450-million design by Michael Maltzan and HNTB — is completed over the Los Angeles River in 2019.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

In its optimism about the emerging Los Angeles, a denser and more vertical city than the postwar one, the 6AM proposal is not so different from the argument made by Maltzan in his design for the nearby One Santa Fe residential block, a design long and low enough to resemble an ocean liner. In both cases the architecture is less a reflection of current conditions on the ground than a bet on the maturation of a new Los Angeles that is more comfortable with density.

Towering development is proposed for L.A.'s Arts District: an 'opportunity for density'>>

The materials Herzog & de Meuron prepared for city officials include a diagram showing the 6AM project as the center of an emerging node for high-rise development, joining existing pockets of vertical architecture in Century City, along the Miracle Mile, in Koreatown and on Bunker Hill.

Though it remains in a conceptual phase, the design has already been through several iterations since SunCal bought the site (which is now covered with warehouse buildings) last year for a reported $130 million. The concrete columns marching around the exterior were skinnier and less muscular in earlier versions. At a certain point the architects considered scattering a series of towers across the site instead of corralling them along the Alameda Street edge.

The changes have improved the proposal, though some obvious risks remain. The biggest is that SunCal, after entitling a large-scale development on the site and securing permission from the city to build, then decides to switch architects or water down the design.

A bigger question is whether this sort of megablock development, so much more intensely built up than the buildings around it, will feel less like an extension of the neighborhood than a contrived stage set for sophisticated urban life, a high-design Swiss spin on a Rick Caruso outdoor mall.

Twitter: @HawthorneLAT

ALSO

D.C.'s new African American museum is a bold challenge to traditional Washington architecture

From UC Davis to the National Mall: Key architecture projects this fall

At Sandy Hook Elementary, a new campus and a new start at site of horror

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.