‘Hamilton,’ the movie? Why screen adaptions of stage musicals take so, so, so long

- Share via

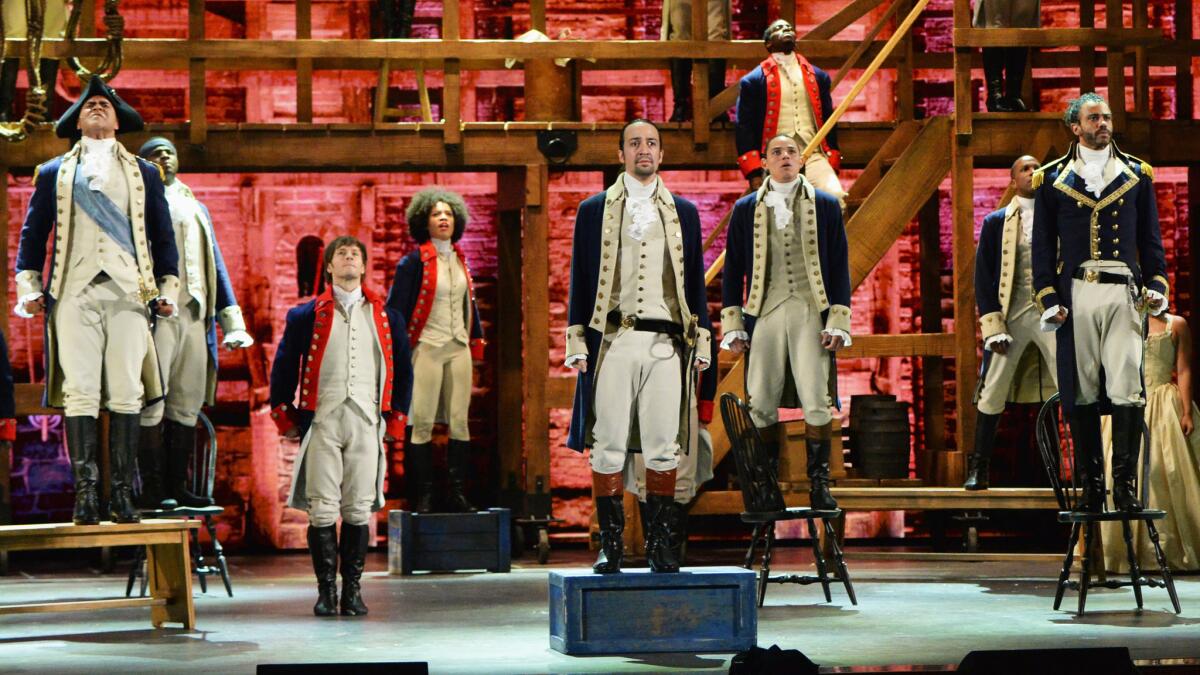

Reporting from NEW YORK — Lin-Manuel Miranda’s “Hamilton” has made history in numerous ways, injecting energy into the musical, populating the stage with people of color and bringing young audiences to a middle-aged Broadway.

But there’s one barrier in which the 11-time Tony winner is unlikely to make a dent: the lag between hit show and Hollywood film.

“I think the show will end up on screen without a doubt,” star and Tony winner Leslie Odom Jr. said at a Tonys after-party Sunday night. “I just think it will be like 10 years from now.”

As with so many big Tony winners before it, “Hamilton” will take a circuitous path to the multiplex, if it gets there at all. In the last decade, more best musical winners have come from films (three) than have been turned into films (one).

No “Hamilton” rights have yet been sold, and at least one film producer told The Times that when they sought to have a conversation about them, the show’s team politely said thanks but no thanks, at least for now.

Musicals are enjoying a mini-vogue in Hollywood, whether it’s original animated pieces like “Frozen” or live telecasts of classics such as “The Wiz” and “Grease.” So why have new Broadway works not been part of this resurgence?

To a large degree it’s because theatrical producers are reluctant to cannibalize sales of hit shows. “Hamilton” is raking in eye-popping numbers on Broadway, nearly $2 million per week. With a national “Hamilton” tour on its way (it arrives in Los Angeles next year), and with possible foreign engagements to come, producers are in no rush to kill the golden goose.

“ ‘Hamilton’ is a show that will make more than ‘Star Wars.’ Why do they have any incentive to try to be like ‘Star Wars’?” asked one Broadway producer who declined to be identified because they were speaking about a rival production.

‘Hamilton’ is a show that will make more than ‘Star Wars.’ Why do they have any incentive to try to be like ‘Star Wars’?

The cautionary tale is “War Horse,” the West End smash whose film adaptation came out in 2011 — the same year the show opened on Broadway . The production ran only about a year more after the movie opened, and many point to the film as the culprit. Why lay down a few hundred bucks on Broadway, consumers reason, when Netflix comes so much cheaper?

Audiences are also less likely to embrace a movie until the original (and often more urgent) theatrical version has receded from memory. The evidence? Some of the most successful modern movie musicals (“Chicago,” “Dreamgirls”) came a quarter-century or more after their Broadway openings. Toss in all of Hollywood’s usual development friction and creative disagreements, and you have a recipe for a lot of waiting.

This larger reluctance plays out in particular ways with “Hamilton,” whose principals have their own reason to be gun-shy.

Miranda has expressed skepticism about cinematic adaptations; if he has Hollywood ambitions, it’s as an original composer or actor — “Star Wars,” a new “Mary Poppins.” (He will work with Harvey Weinstein on another attempt to get his 2008 best musical winner “In the Heights” off the ground and on to a set. Weinstein, who was making the Tony afterparty rounds Sunday night, is keen for another adaptation of a stage hit a la “Chicago.”)

Meanwhile, “Hamilton” producer Jeffrey Seller has his own uneven experience to draw from. Seller was also the man behind “Rent,” the mid-’90s Broadway sensation that in fact helped turn Miranda on to the possibilities of theater. The film came out nearly a decade after the show opened, and still it was a commercial and critical disappointment.

Indeed, capturing the energy of a live show on-screen is an imposing challenge. For every “Chicago,” there are five misfires. “Jersey Boys,” one of the few recent best musical winners to become a film, was a flop, even in the hands of Clint Eastwood and much of the Broadway cast. Ditto for “The Producers,” which retained much of the stage talent behind and in front of the camera when it came out four years later, to a great eye-roll. And let’s not even get into “Rock of Ages” or a “A Chorus Line.”

Years ago in the Hollywood development world, new bits about the film version of “Wicked” arrived with the regularity of an eight-o’clock curtain. “Producer Marc Platt had made new hires, the project had new energy, a movie was imminent” — a journalist heard it all. And still a film waits. “Wicked” has simply been too big a hit in too many places for anyone to rush. Star Idina Menzel, the original Elphaba, has taken to joking that so many years have passed that she couldn’t star in the movie even if she wanted to — unless it was, you know, as the Wizard.

That doesn’t mean Hollywood and Broadway don’t maintain strong ties. It just happens in the other direction. Some of the biggest musical hits or Tony nominees in recent years have come from film, including best musical winners “Once,” “Kinky Boots,” “The Producers” and the 2016 breakout “Waitress.” But the challenges for “Hamilton” will remain in the stage realm.

Indeed, with the show’s Tony triumphs in the bag and its one-year Broadway anniversary approaching, the question will be how to keep the momentum going. Some of that, as recent media speculation has had it, is due to the possible departure of Miranda and other principal cast.

But some of it is also about a show finding a niche. Many of the longest-running productions on Broadway tend to locate a consumer sweet spot. “Jersey Boys” has the people in the New York suburbs. “Wicked” has teenage girls. “The Book of Mormon” has comedy-seeking tourists.

“Hamilton” has a cool factor. But to sell out for years, past a point when it’s novel and when many of the principals have moved on, a show needs to lock down an audience that will come out reliably and repeatedly. In this way, Broadway actually has a lot in common with Hollywood. Finding a target demographic is never easy.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.