Labor strikes, racial violence, class divides: ‘Ragtime’ in Pasadena feels ripped from today’s headlines

- Share via

As Pasadena Playhouse revives “Ragtime,” the theater’s leader wonders whether he’ll receive letters from viewers who believe the piece has been altered.

The 1996 show is based on E.L. Doctorow’s 1975 bestseller, which looks back to the dawn of the 20th century, yet Playhouse producing artistic director Danny Feldman notes that it’s “squarely on the nose about immigration and women’s rights and hints of the Black Lives Matter movement.”

Also: deepening economic divides, labor strikes, sensation-driven news, racially targeted violence and socially aware young people demanding change.

“We’re not changing a word in that show,” Feldman says, “but it feels like it was written for today.”

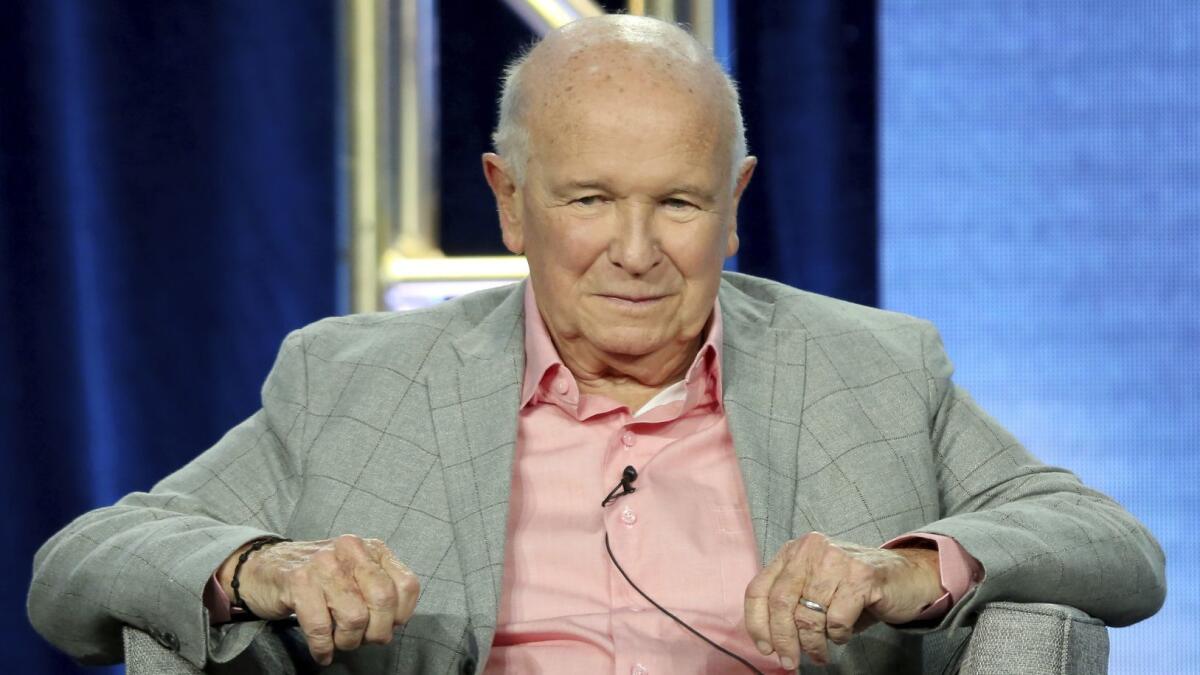

Ticking through the topics, Terrence McNally, the four-time Tony Award winner who wrote the script, marvels, “I’m sure there’s 10 we’re not even thinking of right now.” Had he tried to incorporate everything in the novel, he says, “it would be about a 12-hour musical.”

It’s a big show in every way. The Playhouse is employing 21 actors and 16 orchestra members, among more than 100 theater artists involved in creating the show. The budget is more than $1 million, Feldman says.

“This show is a landmark moment for the Playhouse,” he says, “a big, bold musical that is directly speaking to the community.”

REVIEW: A stunning “Ragtime” revival at Pasadena Playhouse »

In charge of staging the show at the 648-seat theater was David Lee, an Emmy-winning co-creator, writer and frequent director of “Frasier” whose previous Playhouse directing projects included “Can-Can” and “110 in the Shade.”

For theatergoers who saw “Ragtime” at Los Angeles’ Shubert Theatre, where it played from June 1997 to April 1998, one noticeable difference will be the Playhouse’s framing device.

Lee envisions the story unpacking itself from premature storage in a history museum’s dusty warehouse. Metaphorically, “that’s what we do with our past in this country,” Lee says, “but with some regularity the past decides it wants to be heard again. These ghosts that have been packed away are rather insistent about having their story retold. Many of the characters literally come out of crates.”

“Ragtime” teamed McNally — known for such plays as “Master Class” and “Love! Valour! Compassion!” — with lyricist Lynn Ahrens and composer Stephen Flaherty, whose scores include “Once on This Island.”

The show was created by former theatrical producer Livent Inc., which introduced the piece in its hometown, Toronto, then brought the show to L.A. While still playing here, the show opened on Broadway in January 1998 and ran for two years. lt was nominated for 13 Tony Awards, winning four, including book and score.

When there’s acrimony between different kinds of people ... the show just steps forward and has a few things to say.

— Lyricist Lynn Ahrens

Lee, who is 68, says he saw the original L.A. presentation about 10 times. Feldman, who was in high school at the time, lost count of his visits. From West Hills, “I drove to the Shubert Theatre and bought rush tickets,” the 39-year-old says. “I thought it was one of the most incredible things I had ever seen in my life.

“I’m so taken by it,” Feldman continues, because “it’s about America at a moment of extraordinary change and trying to figure out who we are as a country.” The early-1900s characters, he says, are “good people, who are broken in some way, trying to do good, trying to come together.”

Rigid social and ethnic demarcations begin to bend when the matriarch of a wealthy white family in New Rochelle, N.Y., provides shelter to an African American washerwoman who is scared and alone after giving birth. The baby’s father, a brilliant ragtime piano player, becomes a regular visitor too. Meanwhile, the family keeps crossing paths with a Latvian Jewish immigrant widower and his young daughter.

Tying the story together is the metaphor of ragtime music.

“Ragtime was just coming into its own,” Lee says, “and it was the shock of the new. Damn that Doctorow. He found this perfect metaphor.”

Composer Flaherty explains ragtime’s structure this way: Steady, marching notes played by the left hand represent the order of the piece, while the right hand uses syncopated rhythms to go against the order. The name’s derivation may come from “ragged time, meaning something that’s ripped apart. And so much of the action of the show is about ripping against structure, ripping against the old guard, trying to wrestle forward — and at the same time trying to coexist with that structure.”

Ahrens, the lyricist, adds: “You could use the left hand as a metaphor for John Philip Sousa and the music of white society at the time, and the right hand is the mischievous, syncopated rhythms of the new black America.”

The score gives each population its own voice, Flaherty says. The wealthy white family sings polite parlor songs. The Latvian immigrant sounds like Eastern Europe’s shtetls. The piano player conveys the rambunctious energy of ragtime, the sound toward which all the others begin to bend. Sonically as well as visually, the show becomes a melting pot.

Some reviews in the late 1990s labeled the show a period piece, which surprised Ahrens. But the story is “always going to resonate, probably some times more so than other times,” she says. “When times are hard, when there’s acrimony between different kinds of people, when there are crimes of violence because of racism or religious persecution ... the show just steps forward and has a few things to say.”

A flashpoint occurs after the piano player, driving a shiny Ford Model T, attracts the attention of a racist firehouse crew whose station he passes repeatedly on the way to visit his nascent family. Returning from an outing one day, the family is blocked by the crew, which angrily destroys the vehicle. Justice is sought, but none is forthcoming. As tensions escalate, black people die at police hands.

“We did not sit down to write a musical about racism,” McNally says, “but, clearly, racism is at the core of the America experience, and it’s at the core of this story … racism at its most brutal and terrifying.” He quotes the title of a key song, “Till We Reach That Day” — shorthand for a time “when, fundamentally, all men and women are created equal. And we’re not even close to that yet.”

That doesn’t mean that the show is dire, however. Quite the opposite: It continually bends toward uplift.

“There are big tunes, big chorus numbers,” says Lee, who staged the show with choreographer Mark Esposito and music director Darryl Archibald. “There’s spectacle, there are a couple of traditional vaudeville numbers, so in that sense I think audiences will find it extremely accessible. But the bottom line: What makes anything successful are interesting characters and compelling relationships. And that’s what this show has by the gross.”

As much as Lee admired the musical, “it always seemed out of reach,” he says. “I hadn’t thought about how it could be revived in a viable way, because it’s just such an enormous show.”

The original production had a cast of 48 and orchestra of 28, but in a recent flurry of productions, the show has been re-explored with reduced cast, orchestra and designs. “Suddenly, people have discovered not only its political relevance,” Ahrens says, “but the fact that it can be done on a bare stage.”

Feldman and Lee checked out some of those presentations but hesitated to reduce quite so much.

“We both wanted soaring,” Feldman says. So they aimed for big but not gargantuan, shrinking the ensemble but trying not to diminishing the show’s effectiveness.

The Playhouse’s budget for “Ragtime” is roughly double that of either of last season’s large-scale productions of “Our Town” or “King Charles III,” Feldman says. The Playhouse had to raise hundreds of thousands extra, he says, securing grants as well as targeted donations.

He sees “Ragtime” as a way for the Playhouse to engage with broader audiences, continuing the diverse programming of his two seasons as producing artistic director. Shows such as Culture Clash’s “Bordertown Now” and Karen Zacarias’ “Native Gardens,” as well as a blended hearing-deaf production of “Our Town,” have started dialogues and drawn new audiences.

“If you look at the seasons and the artists that we work with, I’m very proud of the diversity,” Feldman says.

“Ragtime” is ultimately about crossing divides and finding unity, redirecting a painful past toward a hopeful future. “But you can’t get there,” Lee says, “with having all these various groups stay separate. It is the mixing of them that leads you to the prospect of hope.”

Feldman believes that attaching the message to music — which “speaks another language that you can’t put into words” — makes it that much more potent. “Musicals have a special power,” he says, “a superpower.”

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

‘Ragtime’

Where: Pasadena Playhouse, 39 S. El Molino Ave.

When: 8 p.m. Tuesdays-Fridays, 2 and 8 p.m. Saturdays, 2 and 7 p.m. Sundays; ends March 9

Tickets: $25-$129

Info: (626) 356-7529, PasadenaPlayhouse.org

UPDATES:

3 p.m. Feb. 15: The ticket information at the bottom of this article was updated with an extended closing date of March 9.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.