Is August Wilson the ‘Shakespeare of our time’? Cast and crew of ‘Ma Rainey’ say you can hear it

- Share via

It’s break time in rehearsals at the Music Center Annex in downtown L.A., and director Phylicia Rashad and actors Lillias White and Keith David exude familial warmth and ebullience as they unpack the musicality of August Wilson’s “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” — not just the blues of singer Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, but the poetry, purpose and lyricism of Wilson’s dialogue.

“I found his language is very musical, but particularly in this play,” said White, who portrays the irascible Rainey. As an actor, “if you stick to what he’s written and stay in the moment, you feel the rhythm and you hear the music in it.”

The revival of Wilson’s powerful, raucous drama is raising the roof at the Mark Taper Forum, where the play, currently in previews, opens Sept. 11. This groundbreaking work, set in Chicago during a highly charged 1927 recording session, features stirring musical numbers including Rainey’s eponymous signature tune. But the playwright, who earned the Pulitzer Prize and the Tony Award in 1987 for “Fences,” was also known to infuse his dialogue with the language and attitude of blues songs, creating a whole different kind of musical effect.

To wit: “What you all say don’t count with me. You understand? Ma listens to her heart. Ma listens to the voice inside her. That’s what counts with Ma,” Rainey says.

“These guys are rich, full, incredible human beings — and thinking human beings, colorful not only in their use of language but the way in which they think and communicate, both with each other and out in the world,” David said.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Veteran film, TV and theater actor David plays Slow Drag, one of the four vibrantly drawn members of Ma’s contentious backup band.

“There is a rhythm in this language that if you betray, you won’t find the truth of,” he said of the distinct cadence of Wilson’s words. “It’s inherent in the language.”

In that way, the actor considers Wilson “the Shakespeare of our time.”

Rashad, the stage director and actress best known for her role as Clair Huxtable on TV’s “The Cosby Show,” noted that if you pay close attention to the entire Wilson canon — his decade-by-decade “Century Cycle” of plays, which includes “Ma Rainey” — and you listen to the rhythm of the speech, “you hear very close connections to African rhythms and you hear how in subsequent decades it begins to shift and change. So when you get to ‘Radio Golf’ [the last play of the Cycle set in the 1990s], the rhythms are very, very different.” Her point: In the end, these innate rhythms have largely disappeared.

Wilson’s concerns about loss of identity are reflected in the battle between Rainey and her fiery band member Levee (Jason Dirden), who wants to jazz up what he deems the singer’s “old jug-band” style of blues.

Wilson wrote about how the play’s title song “is being shifted and changed and how the soul and the essence of it is being bled out,” Rashad said, adding: “August has themes that run through his plays, and [here] he’s talking about the importance of knowing your own self, knowing who you are inside.”

Rashad has become a go-to interpreter of Wilson’s work. She starred in productions of his “Gem of the Ocean” at the Taper in 2003 and the following year on Broadway (earning a Tony nomination), and she directed the play in 2007 at Seattle Repertory Theatre. In 2013, Rashad helmed “Fences” at the Long Wharf Theater in New Haven, Conn., and Wilson’s “Joe Turner’s Come and Gone” at the Taper. The latter production featured “Ma Rainey” collaborators David, White and Glynn Turman, who plays bandmate Toledo in the current production of Wilson’s work.

“He writes about specific time, specific people and specific circumstances,” Rashad said. “And because he is a humanist, there is a universality in all of his writings.”

There also remains a timeliness to Wilson’s works. This may feel especially true of “Ma Rainey,” which premiered on Broadway in 1984. The play involves racism, artistic passion and the longtime exploitation of black recording artists by white managers and music producers.

“We have issues that we as a black people are constantly dealing with in this country,” Rashad said. “Certainly things have changed since Ma Rainey’s time, but we still have a significant amount of activity that is unhealthy not just for black Americans but for white Americans.”

Rashad continued: “We’re being dumbed down by TV and reality shows, libraries are closing, people are not reading and finding out about each other. We’re not learning about who we are and who we were and where we came from. As a result, we have the same kinds of problems and issues that we’re dealing with as you see happening in this play.”

David agreed. “I find it kind of prophetic of August to hit this subject that is ongoing. There’s something sad that we’re still talking about exploitation on a grand level. But it should be brought up. It’ll never change if we don’t talk about it.”

The play also explores the role of women in society and in business. The real Ma Rainey, a.k.a. the Mother of the Blues, recorded almost 100 songs in five years, worked with Louis Armstrong and mentored singer Bessie Smith, whose fame would arguably eclipse Rainey’s.

The trailblazing Rainey was also reportedly bisexual, an “open secret” touched on in Wilson’s play via the singer’s close relationship with a member of her entourage, a young woman named Dussie Mae (Nija Okoro).

Rainey was nothing if not authentic.

“People loved her because she gave it to them raw and real,” White said of her character’s song stylings. And she didn’t take any grief from anyone “because she knew her power.”

For an actor, finding an accessible point of entry to humanize a character as frank, feisty and unapologetic as Rainey could be a daunting task.

White, who won a Tony in 1997 for “The Life,” revealed that she drew from Rainey as well as from another blues great, Dinah Washington, to fashion the part.

“Dinah was very similar in her boldness and her truth and her ability to take care of business,” White said.

The actress said she also pulled from her mother, who was direct. “She told you the truth until it made your eyes sting,” White said. “Took your breath away sometimes.”

David, who can be seen in the new OWN series “Greenleaf,” noted a few personal parallels with the bass-playing Slow Drag, a laid-back pragmatist who gained his nickname at a dance contest. “I have learned how to move through the world and pick my battles,” David said. Using some language that can’t be printed here, he said sometimes you have to put up with a lot of nonsense just to keep other nonsense from happening. He added with a chuckle, “I especially appreciate that now, in my elder statesmanhood.”

Throughout the play, Slow Drag and his fellow bandmates — haunted trumpeter Levee, philosophical pianist Toledo, God-fearing trombonist and guitar player Cutler (Damon Gupton) — banter, debate and argue, each bringing his own perspective to questions of prejudice, African American identity and heritage, the almighty dollar and, pivotally, shoes.

As these musicians tell it like it is, they employ a liberal use of the N-word.

If the loaded language startles or discomforts some theatergoers, Rashad said, as an audience member and individual “you deal with that, you make your decision.”

The director added that Wilson is “capturing people through their speech and through the way people use speech. He’s not giving political or social commentary to the word, nor is he criticizing the use of a word. He’s just showing you how people talk.”

------------

“Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom”

Where: Mark Taper Forum, 135 N. Grand Ave., L.A.

When: In previews now. Opens Sept. 11. Ends Oct. 16.

Tickets: $25-$85 (subject to change).

Info: (213) 628-2772, www.CenterTheatreGroup.org

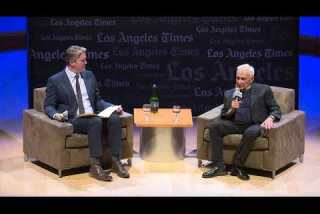

Los Angeles Times Ideas Exchange: Christopher Hawthorne in conversation with Frank Gehry

Frank Gehry’s thoughts on the Broad? Watch his hilarious groan

Watch Frank Gehry in conversation with architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne

Why Frank Gehry never showed up to work for Richard Neutra

Frank Gehry recalls Rudolph Schindler style: Rough, raw and unpredictable

How Frank Gehry defended his Santa Monica home against a critical neighbor

Frank Gehry wants the L.A. River Revitalization project to help the neighboring communities

Frank Gehry’s approach to the L.A. River – a lot of collaborators

Follow The Times’ arts team @culturemonster.

ALSO

Dynamic cast propels tale of two step-siblings across three decades

Frida Kahlo meets John Coltrane in electric dance homage

In this ‘Next to Normal,’ the message is loud but not clear

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.