Why ‘The Good Fight’ is the Trump era’s best political drama: It understood liberals

- Share via

The great American TV shows about politics — which should now include Paramount+ legal drama “The Good Fight,” whose finale airs Thursday — tend to focus on liberals rather than conservatives. In scripted TV, the real partisan divide is where those liberals fall on the earnest-to-cynical spectrum.

NBC’s “Parks and Recreation” and “The West Wing” were aspirational at heart, promoting the view that competent people of good will can defeat political inertia to make the world a better place. It takes endless stamina and almost inhuman optimism to get a city park built in Pawnee, Ind., but bureaucrat Leslie Knope (Amy Poehler) ultimately outmaneuvers her libertarian boss and the public-comment saboteurs who had other plans. President Bartlet (Martin Sheen) had it relatively easy in the orderly Washington imagined by series creator Aaron Sorkin; Barlet and his staffers could simply deploy the powers of logic, persuasion and personal virtue to win over — or at least embarrass — their conservative opponents.

For the record:

8:40 a.m. Nov. 10, 2022An earlier version of this article identified the NBC show “Parks and Recreation” as “Parks and Reaction.”

Netflix’s “House of Cards” and HBO’s “Veep” and “The Wire” held far darker views of political life in America, where the winners are the Machiavellians who can best manipulate public power for personal gain. Congressman Frank Underwood (Kevin Spacey) was a compelling dramatic character because he could play the political game so capably; Vice President Selina Meyer (Julia Louis-Dreyfus) was a compelling comedic character because she couldn’t.

David Simon’s sweeping “The Wire” was bleakest of all, chronicling a rotten system rather than the rotten people working it. “Everybody stays friends, everybody gets paid, and everybody’s got a f— future,” Det. Jimmy McNulty (Dominic West) protests after prosecutors hesitate to confront a corrupt but well-connected defense attorney.

As the series ends, ‘The Good Fight’ star opens up about going from No. 2 to No. 1 on the call sheet and the family wounds she confronted through acting.

“The Good Fight,” which premiered in 2017, became one of our most introspective political shows of the post-Trump era by veering between these poles of idealism and cynicism, wavering as to whether the series’ predominantly progressive lawyers might take the high road or the low. A spinoff of “The Good Wife” — and set, like its predecessor, in one of Chicago’s top law firms — “The Good Fight” regularly indulged in the trusty legal procedural format of ripped-from-the-headlines cases. But it did so in the service of its true obsession: exploring the crisis of self-confidence unleashed in liberals by the shocking 2016 election of Donald Trump.

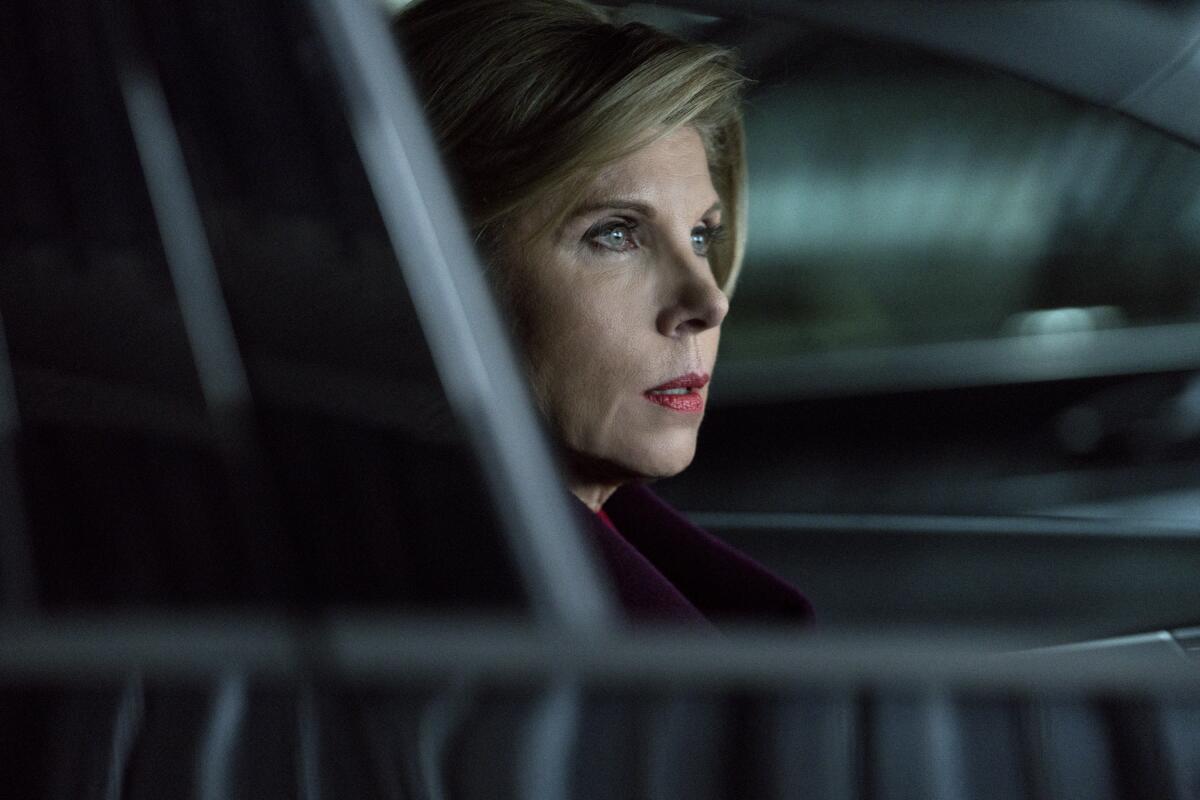

The show’s central character, Diane Lockhart, played in a magnetic performance by Christine Baranski, is a polished legal mind and a suave operator of glass-office politics. She’s capable of meeting nearly any crisis with little more reaction than a lizardlike slow blink — except when she starts to suspect that democracy and the rule of law have started to crumble under the onslaught of right-wing nationalism. Lockhart, willing to put country over family, repeatedly betrays the trust of her doting husband, a National Rifle Assn. activist (Gary Cole). But deep down, Lockhart barely knows what to cling to apart from her patriotism. She spends much of the series on hallucinogens.

The philosophical (and sensory) ambiguity at the center of “The Good Fight” is often played for laughs; to its credit, the series is tremendously funny, enlivened by guest-appearance chaos agents like conniving Democratic party boss Eli Gold (Alan Cumming). But creators Michelle and Robert King‘s deployment of surrealism was also an effective technique for illustrating liberals’ utter loss of control, in multiple senses of that word, after the rise of Trump, his transformation of the Supreme Court and his supporters’ violent sack of the U.S. Capitol building on Jan. 6, 2021. It’s the kind of show where the ghosts of Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Frederick Douglass appear to characters experiencing crises of conscience (or cognition).

Hyped-up political violence is practically part of “The Good Fight” set. Mobs with deliberately vague alliances thrash in the streets below the firm’s offices, whose windows get shot out by small-arms fire from the latest would-be assassin. In their day jobs, the firm’s progressive lawyers might coo to an unqualified judicial appointee in one scene and dodge emboldened white nationalists in another.

On the side, multiple characters join insurrectionary organizations that are willing to do what the Democratic Party or the legal system won’t. Visual motifs from the real-life 2017 “Unite the Right” rally of white nationalists recur throughout the series, a khaki-and-tiki-torch reminder of the barbarian armies lurking on the frontiers of liberal tolerance. It’s not a subtle show. But these are not subtle times.

“The Good Fight” was never that interested in Trumpism itself, whose Republican avatars appear onscreen mostly as cartoonish foils to the show’s anxious and befuddled progressives. In one familiar trope of “The Good Fight” season finales, high-powered lawyers gather in a corner office, gaze out the firm’s window, and take stock of the right-wing upheaval that sees liberal professionals and institutions as enemies that need to be swept aside. “Everybody running around out there, doing God knows what,” partner Adrian Boseman (Delroy Lindo) mused at the end of Season 1, then offering a note of reassurance: “The only constant is the law.”

“Do you still believe that?” Lockhart asks Boseman an anarchic season later — this time drawing a notably hesitant “yes” in reply. “What does it matter if we’re a country of laws if the laws aren’t just?” asks a third partner, Liz Reddick (Audra McDonald). By Season 3, despair had all but set in. The only thing left for a democracy-loving lawyer to cling onto was “love,” Lockhart tells a now-despondent Boseman. And “hope.”

Robert and Michelle King, the pair behind ‘The Good Fight,’ aren’t aiming for Shakespeare. But they’ve made the audacity of immediacy into high art.

But “The Good Fight” was too sly and incisive to cling long to these sorts of pieties. The series, which sometimes veered into manic adventures involving the mythical Trump “pee tape” or the jailhouse death of financier-predator Jeffrey Epstein, was always at its most bracing when skewering the all-to-real hypocrisies and contradictions straining liberal institutions from the inside. The firm was founded by Reddick’s father, a civil-rights legend who, after death, is discovered to have been a sexual predator; Reddick investigates but covers up the findings. The arrival of white attorneys like Lockhart, who help boost the firm’s business, instigates an identity crisis as well as a pay equity insurrection among the firm’s left-wing staff. Lockhart, a proud feminist, struggles with the suggestion that she should put her career on the back burner for the sake of avoiding the political awkwardness of becoming a white leader of a Black firm.

And although that firm prides itself on do-gooderism, it also likes raking in nice profits — even if it means protecting unsavory but wealthy clients. In one of the series’ most righteous betrayals, Lockhart’s estranged mentee Maia Rindell (Rose Leslie) sues and charges that the firm is skimming 60% from its clients’ awards in Chicago police brutality cases. “Why come after us?” Lockhart asks, presuming a personal vendetta. “Because you’ve done wrong,” Maia responds, noting that the firm was making more money than its exploited clients. “You had a conflict of interest, and yet all the while, you were patting yourself on the back, thinking you were fighting the good fight.” Ouch.

For most of the series, “The Good Fight” doesn’t provide the answers as to how liberals should respond when their beliefs and their way of life come under threat. The wannabe heroes hoping to change the whole world — or who carry on the fight just to drown out some emptiness inside — risk toiling in aimless misery, or worse, inflicting pain on those closest to them. But in the end, “The Good Fight” keeps the faith. If the world changes for the better, the show suggests, it will come millimeter by millimeter, in exhausting, infuriating, messily human increments.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.