The contentious presidential campaign was filled with accusations of elitism and bias by the media -- from the news to entertainment. Many supporters of Donald J. Trump saw his victory as a repudiation of the so-called liberal elite.

So as 2017 begins, we ask: Is Hollywood representing all Americans? Are Hollywood values out of sync with American values?

It’s the start of a conversation we’ll have all year with Hollywood’s creators, consumers and observers. Most of all, we want to hear from you. Is Hollywood out of touch with your America? Here’s what our critics and writers have to say:

- Blame the movies? KENNETH TURAN on potent Hollywood visions that helped elect Trump

- TV’s affluent bubble: MARY McNAMARA on Hollywood’s reluctance to deal with class issues

- Fear of the powerful woman: JUSTIN CHANG on working women and men still behaving badly

- Realistic or cliche?: JEFFREY FLEISHMAN on film’s working-class men and women

- Building distrust: LORRAINE ALI on destructive TV portrayals of Muslims and how TV can help fix things

- Video games to politics: TODD MARTENS on how Gamergate trolls helped set Trump’s political attack playbook

- No ‘Middle’ ground: MEREDITH BLAKE on TV’s working-class hero, ‘The Middle’

- Bracing for backlash: TRE’VELL ANDERSON on LGBT Hollywood’s vow to keep fighting

- Still angry: MARC BERNARDIN on ‘This Is Us,’ a rare TV view of simmering rage in a black professional

- Arts fighter: MARK SWED says maybe Sylvester Stallone wasn’t such a bad idea for the NEA after all

- Rap pirates: Run the Jewels’ Killer Mike and El-P get political with RANDALL ROBERTS

- Standing Rock legacy: CAROLINA A. MIRANDA on the pipeline protest that could be the future of dissent

- Cuba unplugged: RANDY LEWIS on a music scene that grew up in isolation

- Voice of protest: Conor Oberst talks with AUGUST BROWN about music’s power

- The provocateur: CAROLYN KELLOGG on Milo Yiannopoulos’ $250,000 book advance

- Survival kit: JOHN SCALZI’s 10-point plan for making art in the Trump era

- Share via

There are few platforms bigger than Oscar night. Will A-list actors use it to talk Trump?

WHEN EMMA STONE, DENZEL WASHINGTON, Ryan Gosling and the rest of this year’s Academy Award nominees get ready for the big night, they will reckon with the perennial questions that have faced every Oscar nominee for time immemorial: what to wear, who to bring as a date, who to thank if they win.

But this year, there will be a potentially vexing new question as well: what, if anything, to say about Donald Trump.

If last year’s awards season chatter was dominated by the roiling #OscarsSoWhite controversy, the elephant in the room this year has been the ascent to the presidency of a man whose candidacy few in Hollywood supported and whose victory even fewer saw coming.

At every turn — on red carpets and late-night talk-show couches, at film festivals, premieres and awards shows, on social media platforms and in protest rallies — many across the liberal-leaning industry are wrestling with how to speak publicly about a president they may bitterly oppose and a political landscape that seems to have radically changed overnight.

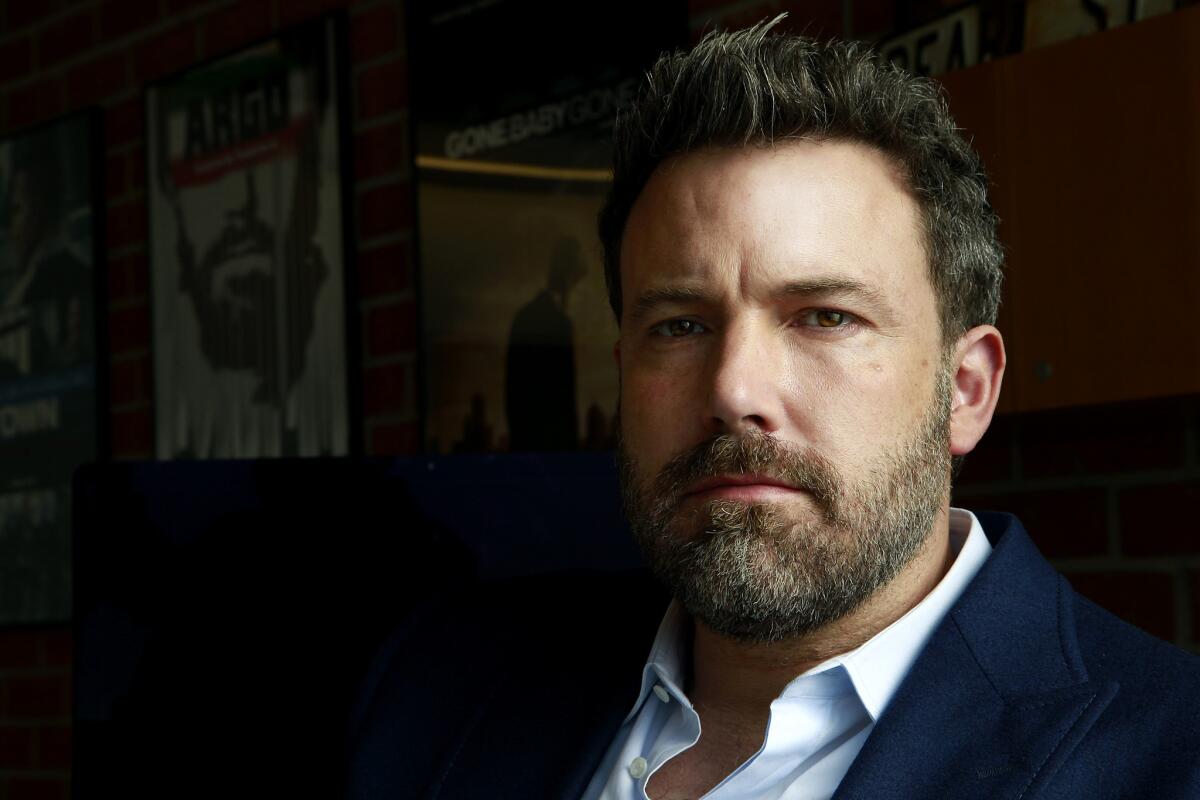

“If you’re in the radius of the earthquake, you absorb the shock of it and then you try to orient yourself and figure out what this new world looks like,” actor and director Ben Affleck, who supported Hillary Clinton, told The Times last month. “I definitely went through that with the Trump election. I was surprised. I thought she was going to win like everybody else. Everyone was totally wrong and you go, ‘How does that happen?’”

Some in Hollywood have embraced the chance to stake out full-throated opposition to Trump, establishing a new beachhead in the latest flare-up of the culture wars that had largely quieted during the Obama years. That Trump drew fire for his comments on women and minorities throughout the campaign has, for many, changed the calculus of celebrity activism, making speaking out a moral imperative.

But sharing one’s political opinions while, say, accepting a gold-plated statue has always been tricky business under the best circumstances. (Ask Vanessa Redgrave. Or Marlon Brando, who famously sent Native American rights activist Sacheen Littlefeather in his place in 1973.) And in this climate of rancor and deep division, it can reap an especially fierce blowback.

While some feel compelled to use their public platform as a means of political resistance, no matter the potential consequences to their career, others believe it can be counterproductive, reinforcing the notion that Hollywood lives in its own self-satisfied bubble.

Last Sunday, after millions marched in protests around the world — including stars such as Scarlett Johansson, America Ferrera, Janelle Monae and Madonna — Trump amplified this notion, tweeting “Celebs hurt cause badly.”

It took this horrific moment of darkness to wake us the f--- up.

— Madonna

The fact that Trump is himself, in many ways, a creature of the entertainment industry, able to leverage his own celebrity and skills as a showman, makes him that much more formidable an adversary.

There are those, such as filmmaker Ava DuVernay, who believe that the best way to resist the new president is to simply concentrate on creating work that reflects their own values.

“I refuse to spend the next four years living in that man’s head,” DuVernay told The Times recently at an event in Los Angeles celebrating her Oscar-nominated documentary about race and the criminal justice system, “13th.”

“One day it’s Meryl Streep, the next it’s [Rep.] John Lewis,” said the filmmaker, who also directed the 2014 civil rights drama “Selma.” “If I spend my time focusing on that spectacle of distraction, it will diminish me. What I need to do is to live fully, move forward and make the art that I want to make.”

Not that that will stop awards show hosts from going after Trump — for them, the president is simply too big and juicy a target to resist. Jimmy Fallon called out Trump recently at the Golden Globes, and Jimmy Kimmel, this year’s Oscar host, laid into him when he hosted the Emmys in September, blaming “The Apprentice” producer Mark Burnett for helping launch Trump. (“Thanks to Mark Burnett, we don’t have to watch reality shows anymore, because we’re living in one,” Kimmel quipped.)

But it’s one thing for a late-night talk show host or comedian to go after Trump and quite another for A-list actors to openly wear their politics on their sleeves.

“The country is pretty divided down the line, so you’re going to run the risk of there being a public outcry if you’re in a campaign for anything, whether it’s dogcatcher or an Oscar,” said one publicist who has worked on numerous Oscar campaigns and declined to speak on the record because of the sensitivity of the issue. “A lot of these people want to avoid controversy of any kind in the press. If you’re asked what you think about the current political situation, you’ve got to weigh what it means in Hollywood versus what it means in the rest of the country.”

That divide was starkly revealed earlier this month when Streep took the stage at the Golden Globes ceremony to deliver an impassioned speech decrying what she called Trump’s tendency to “bully others.” Though Streep’s words were met with cheers from the crowd in attendance — not to mention many viewers watching at home — numerous conservative commentators and supporters of Trump quickly dismissed the actress as an out-of-touch Hollywood elitist.

The next day, Trump himself blasted Streep on Twitter as “one of the most over-rated actresses in Hollywood” and “a Hillary flunky who lost big.”

On the flip side, Nicole Kidman drew fire recently when, in a recent BBC interview about her new movie “Lion,” she said of Trump: “He’s now elected and we, as a country, need to support whoever’s the president because that’s what the country’s based on.” After her comments sparked outrage among some on the left, Kidman clarified in a subsequent interview that she had been simply “trying to stress that I believe in democracy and the American Constitution.”

For public-relations reps responsible for helping celebrities nurture and maintain their images, advising clients on how to navigate the minefield of this new political reality can be difficult.

“It’s a personal decision,” one publicist said of stars expressing their views on Trump. “But would I recommend it? Of course not. At this point, with social media being as venomous as it is and trolls being who they are, I don’t think you can basically be safe with your opinions anymore. It’s a dangerous time. … Even Meryl Streep and George Clooney want to work. They don’t want to be considered liabilities.”

Actress Zoe Saldana told an Agence France-Presse interviewer earlier this month she believes that Hollywood unwittingly helped to elect Trump by alienating a large swath of Americans. “We got cocky and became arrogant and we also became bullies,” she said. “We were trying to single out a man for all these things he was doing wrong ... and that created empathy in a big group of people in America that felt bad for him and that are believing in his promises.”

Director Peter Berg, who helmed the recent ripped-from-the-headlines films “Deepwater Horizon” and “Patriots Day,” argues that Hollywood is too often out of touch with the type of people who supported Trump who, broadly speaking, live in what the industry considers flyover country.

“‘American Sniper’ made almost $400 million — do you think anyone saw that coming? A movie about an extremely conservative Republican Navy SEAL who kept a record of how many Taliban he killed?” Berg said in an interview with The Times last month, referencing director Clint Eastwood’s runaway 2014 hit.

That said, Berg said he personally makes an effort to steer clear of overt politics in his work and outside of it. “I accept that Trump won the presidency and I’m going to deal with it, and I would have accepted if Hillary won,” he said. “Guys that I know, we’re too busy working to get involved in this. We’re making stuff. I’ve got work to do.”

Some minority actors and filmmakers in particular lament that they are asked to address questions of race and politics disproportionately compared with their white counterparts — especially this year, as Trump’s rise has heightened tensions around issues of diversity and discrimination.

“Fences” star Viola Davis said that because the film, which is adapted from August Wilson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play, has an almost entirely African American cast, people often try to make race its central subject as opposed to broader issues of family dynamics and working-class struggle that the film explores.

While Davis doesn’t shy away from talking about politics, she argues that those larger conversations often become problematic when they’re reduced to sound bites or hashtags.

“I’m just not a political statement,” Davis said. “I’m messy too. I fall short all the time. I’m a human being. And a lot of times I feel that’s the best message I can put out there.”

For her part, DuVernay hasn’t done many interviews to promote “13th,” believing that the documentary speaks for itself. She wants people to have their own conversations about the film, unfiltered as much as possible by her personal political views.

“Take it for what it is,” DuVernay said. “I said my piece, and now I’m going to keep on living and keep on trying to survive in an environment that is so toxic. Everyone has to find their way forward. I’m not saying that my way is anyone else’s way. My way is going to be telling stories that amplify the parts of humanity that I think we should be celebrating and saluting.”

Though in the past he has been one of the industry’s most outspoken liberal voices, Affleck said he personally has lost some of his appetite for politics. “I’ve grown leery of being involved in politics too much,” he said. “I’ve found that it’s kind of a sleazy game, mostly about raising money. I’ve come away feeling more depressed about the world than when I got involved to begin with.”

Still, as Hollywood tries to figure out its place in the new Trumpian era, he said it’s important to stay engaged, whatever form that engagement takes.

“You have to have a good relationship with the audience,” he said. “You have to be mindful of the audience. As a filmmaker, you don’t want to be out of touch with what’s going on in the world. That’s actually the worst thing that can happen to you.”

The fact is, as the Women’s March last weekend made clear, resistance to Trump has become something of a crusade for many on the left.

And while it remains to be seen how politically charged this year’s Oscars ceremony will become, there are few platforms bigger than the Academy Awards stage from which to send a message.

One thing seems safe to predict: Come Oscar night, if “Hamilton” creator and star Lin-Manuel Miranda — a best song nominee for the film “Moana” — has the chance to share his political point of view with an audience of millions, he’s not throwing away his shot.

- Share via

Is Hollywood out of touch with American values? Join Mary McNamara, Marc Bernardin, Lorraine Ali and Justin Chang

- Share via

A decade after protesting Bush’s election, Conor Oberst wonders what Trump means for art

THE DAY AFTER THE 2016 ELECTION, Conor Oberst called his old friend Michael Stipe from R.E.M. for condolence.

“He’s someone I look up to as a voice of reason,” Oberst said. “He was torn up about it all, but good to talk to. He said that now’s the time to find more resolve than ever to donate to Planned Parenthood and all the institutions that we’re going to have to rely on.”

The two had performed, with Bruce Springsteen, on the Vote for Change tour in 2004, hoping to rally support for John Kerry’s ultimately unsuccessful presidential campaign. That was the last time the singer-songwriter felt so despondent about American politics. Until November, that is.

“I think this [election] is worse. But I felt more freaked out in ’04. Maybe because I was younger and less cynical.”

— Conor Oberst

“I think this [election] is worse,” Oberst said of the election of Donald Trump as president. “But I felt more freaked out in ’04. Maybe because I was younger and less cynical.”

People like to joke that at least the protest music will be good in the Trump era. Right now, though, it’s hard to imagine that anyone much feels like dancing. But for fans around the 36-year-old Oberst’s age, listening to his older music now can stir up those same feelings of being young, outraged and despondent about politics. His new music might be even more harrowing.

Is Hollywood out of touch with your America? Tell us >>

Bright Eyes’ 2005 album “I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning” was lauded for its ten 10 songs of immaculate, articulate folk-rock that will probably stand as Oberst’s lasting achievement. It had moments of shuddering fury, but for many fans, it brought a quiet dignity to what felt like total helplessness in the face of an election loss. They were afraid that that the Iraq war would never end, that gay marriage was impossible, that America had re-elected (by an even greater margin than before) a president who to many seemed like a distillation of America’s darkest tendencies.

I went go to see Oberst last month at the Immanuel Presbyterian Church in Koreatown. He played a few solo dates to support his new album, “Ruminations,” which has earned comparisons to Springsteen’s “Nebraska” for being a minimalist, almost demo-quality recording that nonetheless captures a bleak mood of its own. It’s spare and harrowing in a way we haven’t heard from Oberst since he was a quivery 19-year-old, spinning gothic folk tales from his frigid corner of the Midwest.

But mostly, I went to that show because Oberst’s voice had walked me through my last bout of dark thoughts after a presidential election, and for the first time in a long time, I felt like I needed it again.

Oberst had one of the few good protest songs of the George W. Bush era. I still remember seeing him Oberst perform “When the President Talks to God” in an outsize cowboy hat on “The Tonight Show With Jay Leno,” in an outsize cowboy hat, and thinking that somewhere, an FBI file was being hastily assembled.

“At the time, we felt like we had to do something,” Obsert said. “I was nervous when we did the [stage] blocking, and started to freak out. I was just wearing a hoodie, and I thought, ‘No, I need a cowboy suit, something to hide inside where if you were just flipping through the channels in the South, you’d think, “Hmm, he looks like a nice lad.” ’ ”

But even in protest, his music at the time of “Wide Awake” was graceful. It was richer and more personal than much more overtly protest music usually rarely is. It wasn’t just railing at bad policy; it was ten 10 vignettes of feeling utterly lost and packing up and moving to a place where you felt more wanted.

For me, that was L.A. For Oberst, it was New York. and To this day, few records better capture the transcendence and loneliness that comes from being young and packing up and starting anew. Flasks on the subway after dark; protest marches that did nothing but meant everything; a dawning of how big and terrifying the world was, but also how rare and valuable your refuges were in the midst of it all.’ve seen the future, brother. It is murder.”

Music is unique because it can get behind enemy lines and affect people. Some kid in Utah can get his hands on a Clash record and be introduced to whole new ideas, and that’s still a powerful thing.

— Conor Oberst

“Music is unique because it can get behind enemy lines and affect people,” Oberst said. “Some kid in Utah can get his hands on a Clash record and be introduced to whole new ideas, and that’s still a powerful thing.”

At the Koreatown show, hearing Oberst’s voice singing “Lua” again, in the dead silence in of an actual sanctuary, was both a great comfort and almost a cruel joke. All that work of the last eight years to make the world more just, and now we’re back right back here again.

Even before all this, Oberst had had a very rough few years, dealing with a since-retracted accusation of sexual assault and a brain cyst.

I don’t know what the new era of protest music will sound like. I know it will be black, it will be Latino, it will be Muslim and indigenous and it will be done by women and members of the LGBT community. These are the people with much to lose in Trump’s America, and they should be listened to with moral authority now.

The best artists making protest music today — Beyoncé, Kendrick Lamar — use the personal to catalyze the political. Insisting on the validity of your life and emotions in the face of it is an act of bravery.

“I don’t know what Trump means for art,” Oberst said, “but art does thrive in adversarial times, so hopefully, people will continue that.”

Stumbling out of that church after the show, I was reminded by Oberst’s performance, I was reminded that protest music isn’t necessarily about affecting change or fixing things. Making music at all can be an act of defiance, if just to say that you existed and felt this way at one a specific time, in spite of every reason to despair and stay quiet.

“Go listen to ‘The Future’ by Leonard Cohen,” Oberst said. “It sums up the dark side of my perspective and it pretty much envisions Trump’s America: ‘Give me crack and anal ... sex, take the only tree that’s left… I’ve seen the future, brother. It is murder.”

Twitter: @AugustBrown

- Share via

Art, celebrity and how Standing Rock will shape protest in the Trump years

EARLY IN APRIL, a time when the frigid North Dakota plain is still quilted with snow, several dozen Native American men and women set out on horseback for a 25-mile ceremonial ride from the Standing Rock Sioux tribal headquarters in Fort Yates to the confluence of the Missouri and Cannonball rivers.

There they set up a small encampment of tepees on a site known by Native Americans as Sacred Stone. The camp was a protest against an encroaching crude oil channel, the Dakota Access pipeline, whose placement underneath the Missouri River threatened a key waterway and Sioux burial grounds.

At that moment, it might have strained the imagination to believe that nine months later, the camp would not only still be active but that it also would have become a full-fledged cultural touchstone.

Is Hollywood out of touch with your America? Tell us >>

Standing Rock has galvanized thousands of Native people from all over the continent — along with thousands of non-Native supporters. It has introduced phrases such as “mni wiconi” (Lakota for “water is life”) into the popular parlance. And it succeeded, at least for the short term, in its mission — to persuade the Army Corps of Engineers to block a permit for the pipeline.

No matter what ultimately happens with the pipeline, Standing Rock has also demonstrated the vital role of culture in protest and the direction that protest might take in the future over other issues.

At its core, the Standing Rock protest has been a Native American one, with Native iconography, language, ritual and architecture. But beyond Native communities, it’s also a cultural encounter that has provided fresh ways of thinking about everything from the contours of the landscape to the nature of protest.

Standing Rock, says Nato Thompson, artistic director at the New York-based arts nonprofit Creative Time, “represents an important kind of learning curve.”

Recent social movements in the U.S., such as the anti-globalization protests of the 1990s and the Occupy Wall Street movement that began in 2011, championed issues of economic inequity that are still part of the national conversation. But these movements were far less adept at contending with the ethnic and racial issues that intersected with that concern.

Coming on the heels of the Black Lives Matter movement, Standing Rock has been different, says Thompson. “There was a profound wrestling with race and culture as it applies to class,” he says.

And that could inform the types of protest actions we see in the coming months and years.

“The dominant social movement is going to be a pushback against the [Donald] Trump administration,” Thompson says. “It will be extremely galvanizing across a broad spectrum. So I think the issues of Standing Rock — centered around prayer, around humility, around landedness — could be part of a larger movement across America.”

Since summer, a cross-section of cultural figures, from painters to photographers to musicians to actors, have been involved in Standing Rock — as activists, supporters and artists.

Artist Guadalupe Rosales, known for creating the Chicano youth archive “Veteranas and Rucas” (currently on view at Los Angeles’ Vincent Price Art Museum), ferried winter supplies to North Dakota in her truck. Melissa Govea, of the Los Angeles collective Ni Santas, helped fabricate protest signs at an art tent in one of the camps. The punk/hip-hop L.A. band Aztlan Underground played a concert at the Red Warrior camp over Thanksgiving as a way of lifting morale.

Actress Shailene Woodley has supported Standing Rock since August, through public appearances and by making a number of trips to the area to participate in some of the actions. In October, Woodley made headlines when she was arrested with more than two dozen other people during an attempt to blockade the pipeline route. This was the moment many beyond the Native and protest communities first became aware of Standing Rock.

Artists in the U.S. can play a marginal role in political life, so their gestures are often treated sensationally or skeptically by the press. (Sample headline: “Shailene Woodley Knows She’s Not Saving the World.”) But this type of involvement is hardly new.

Actress Jane Fonda, who has a lifetime of activism under her belt, has publicly supported the #defundDAPL (Defund the Dakota Access pipeline) cause on social media, has donated shelters and bison meat to camp kitchens and flew to North Dakota in late November to help serve Thanksgiving meals. In December, she withdrew her funds from Wells Fargo as an expression of public protest, since the bank has invested in the pipeline project.

“Throughout history, actors have stood up to power,” Fonda told The Times at a December Standing Rock event held at the Depart Foundation, an arts space in West Hollywood. “Artists in general, through their writing, through their plays, through their acting, through their art — it’s very natural for artists to be standing with Standing Rock.”

At its core, the Standing Rock protest has been a Native American one, with Native iconography, language, ritual and architecture.

More significantly, artists of all races and ethnicities were on hand to take part in an unprecedented cultural event — a large gathering of Native Americans that required non-Natives to adapt to the Native way of doing things.

“It’s a whole different reality out there,” says Andrea Bowers, a Los Angeles-based artist whose work has explored issues of solidarity and protest. “It’s a different set of rules. It’s based on Native prayer and spirituality, and there’s a different hierarchy of power, so it’s necessary to just step back and be in service.”

Susanna Battin, another Los Angeles-based artist, whose work often engages issues of water and landscape, had a similar experience during her November visit.

“The media coverage has been about the conflict and confrontation,” she says. “But this was a historic cultural moment — the collaboration, the listening, the breaking down of colonial misconceptions, the style of leadership that we in middle class white America just haven’t experienced.”

Outsiders, in fact, were given an information packet that outlined the ground rules when they arrived. Among these: “Follow indigenous leadership,” “understand this moment in the context of settler colonialism,” “never attend a ceremony without being expressly invited.”

“This is our culture,” says Cannupa Hanska Luger, a New Mexico-based artist who was born on the Standing Rock Reservation and has participated in the protests since they began. “This is why we say this is not a protest, why we are ‘water protectors.’ We’re not just in protest of a pipeline. What we are trying to do is maintain a cultural practice.

“Our original bible, that comes down from on high, it is the land. We tell stories about magical characters that are bound to the landscape. Why is that stone red? There is a story. So where everyone else sees a pipeline and ‘progress,’ what we see is someone going through our bible and editing things without any care, ripping a line straight through that story.”

The Native-focused culture of Standing Rock is part of what drew hundreds of indigenous people from all over.

“That was the motivator for me to go,” says Raven Chacon, an Albuquerque-based artist who is an enrolled member of the Navajo Nation — and part of the contemporary arts collective Postcommodity. “What you saw was truly a global community, but with the majority of them being American Indian people. That was something I’d never seen in my life.”

Standing Rock has been transformative for non-Natives too.

Doug McLean is a longtime environmental activist and photographer who went to Standing Rock on numerous occasions in the summer and fall.

“When I worked at Greenpeace,” he says, “there was the concept that it was founded on which was the Quaker principle of bearing witness. The best journalists and the best artists are the ones who get the most out of the way and are simply a lens.”

Bearing witness is exactly what many of the artists at Standing Rock have done — and it is already filtering into their work.

Luger created dozens of mirrored shields from Masonite and reflective vinyl that were as much protective devices for frontline protestors as they were bright works of sculpture. Bowers took pictures around camp; Battin, of the industrial pipeline architecture penetrating agricultural fields. Chacon, who was inspired by Standing Rock’s sonic qualities, recorded audio of one of the prayer-filled actions.

“What you saw was truly a global community, but with the majority of them being American Indian people. That was something I’d never seen in my life.”

— Raven Chacon, artist

“All of the women in the camp walked onto the bridge, which has been a site of contention,” he says. “About a thousand women walked up there in complete silence. So I was able to capture the sound of a thousand people being completely silent. The only sound you could hear was drones. It was surreal.”

How exactly some of these elements will work their way into art, and, ultimately, the larger culture, remains to be seen. But as with Occupy, which helped inspire a wave of artist-activist movements, some of which are still active, Standing Rock is set to have a cultural butterfly effect.

Molly Larkey is a Los Angeles sculptor who went to Standing Rock over Thanksgiving weekend. During her journey, she collaborated with photographer Jen Rosenstein to create a record of the myriad individuals who attended the protest.

“I’m really interested in that what Standing Rock did was show how things can be different, how culture could be different,” she says. “I’m really interested in how we organize our money, how we can create different kinds of economies.

“It can be things that happen in small ways too. How we relate to each other, for example. At camp, you were encouraged to slow down, be receptive, listen. It reminded you how important those things are.”

“I don’t know anyone whose life wasn’t changed by being there,” says Joel Garcia, co-director of the Boyle Heights arts nonprofit Self-Help Graphics, who traveled to Standing Rock over Thanksgiving with a group of Chicano artists, many of whom observe indigenous traditions as part of their Mexican heritage. “It recalibrates things for sure.”

Bowers, who was at Standing Rock when a group of U.S. military veterans arrived in support of the protest, was moved by the nature of group dynamics motivated by respect.

“To see Native and white vets get into arguments, then have them talk it out, and in the end, I’d see them hug each other — saying, ‘You’re here, you are family now,’ ” she says. “It’s not the way we do things. This was a respect to culture and the process embodied that — everything embodied that.”

- Share via

Run the Jewels talk about writing their latest album with the ‘world crumbling around us’

IN EARLY DECEMBER, while Killer Mike waited in a Hollywood rehearsal space for El-P, his musical partner in the acclaimed rap duo Run the Jewels, the subject of politics and movies came up.

Killer Mike (born Mike Render), who in 2016 channeled his thoughtfully blistering verses on race and class into action by endorsing and campaigning with Sen. Bernie Sanders during the Democratic presidential primaries, had just seen a trailer for the forthcoming “War for the Planet of the Apes.”

He was worried, he said, that the franchise had become “sanitized.”

“It’s like they depoliticized them,” said Killer Mike, contrasting the reboot series with the allegorical first “Apes” films of the late 1960s and ’70s.

“What made movies at that point great — and TV probably until about the early ’80s — was that it was so provocative,” Killer Mike said. “ ‘All in the Family’ was good because it was provocative. I remember ‘The Jeffersons’ episode with the Klansman — George saves his life and he was like, ‘You should have just let me die.’ ”

Is Hollywood out of touch with your America? Tell us >>

Seeing that episode as a kid required that Killer Mike, now 41, “think it through and grow out of your own little bigotry — and still have a good time.”

A similar duality marks “Run the Jewels 3,” Killer Mike and El-P’s decidedly nonsanitized third album, which was surprise-released on Dec. 24. “RTJ3,” a notably dark record with the occasional ray of light, was written and recorded with the divisive presidential campaign as the backdrop, and as both lost close friends.

Tapping at his phone while camped out on a couch, Killer Mike pulled up the “Apes” trailer. As grim theme music played, a menacingly deep-voiced character said, “I did not start this war. I offered you peace. I showed you mercy. But now you’re here to finish us off.”

His eyes lighted up with excitement. “I’m going to one of those fancy movies to see this... where you can buy dinner.”

El-P, his hair still wet from a shower, rolled into the room, casually dropped a joint on the coffee table as he sat down and started talking about writing and recording “Run the Jewels 3” during what Killer Mike called “tumultuous times.”

The dilemma across 2016 lay in how much politics to include in a creative project that began as a way for a pair of middle-aged solo artists to blow off steam and have fun making rap music together.

El-P (Jaime Meline), who didn’t campaign for anyone but supported his partner’s Sanders stumping, acknowledged their competing reflexes: “You see people wanting [artists] to say something when no one is — and then you see people being exhausted by people saying something.”

Mixed into the mess, he added with a cuss, was “having our own ideas of the type of records we would love to make if none of that … was there.” The result, said El-P, were tracks on the album “written almost in despite of the the world crumbling around us.”

“To borrow a phrase from a television show, ‘Winter’s coming,’ ” said Killer Mike. “I felt like that making this entire record. I felt a darkness.”

As with the first two albums, “RTJ3” mixes Killer Mike’s searing insights, from the perspective of a black Atlantan with a cadence to match his acuity, with El-P’s beat production and razor-witted, eloquent couplets as a white Brooklynite whose work as a rapper and producer has earned him underground respect and acclaim.

Across its discography, the team hasn’t avoided hard questions about race, law enforcement and politics — nor have the two shied away from exploring the deeply personal and their love of the kind of hip-hop revelry that defines their favorite albums.

As they started writing in December 2015, El-P said the two didn’t discuss overarching themes or decide to devote themselves to making a political record. Most important, he said, was documenting “the temperament of the last couple of years for us and being friends. Being in it and being affected by the world around us.”

It may be hard to see the playfulness and fun amid the darkness, he added, but that’s a huge part of what they want out of their work. So is “how we are with each other, no matter what’s going on,” El-P said. “We’re still smoking weed and cracking jokes and hanging out with each other and enjoying each other’s company. And that is the foundation of the record.”

But that was apparently easier said than done, because “Run the Jewels 3” opens with a Killer Mike-rapped indictment.

I was campaigning with what I felt like was a good man for good reasons and ... I saw good people doing atrocious things to sabotage that.

— Killer Mike on campaigning for Bernie Sanders

Torn between competing instincts from verse one, Mike sets “Down” in a room with two things before him. “Ballot or bullet, you better use one,” Mike raps as he name-checks three different amendments to the Constitution: “One time for the freedom of speeches / Two time for the right to hold heaters / Just skip to the fifth with the cops in the house / Close your mouth and pray to your Jesus.”

Stumping for Sanders, Killer Mike said, made him increasingly disillusioned as the year wore on.

“This country is going … mad. Let’s just be honest. I was campaigning with what I felt like was a good man for good reasons — and in the middle of that I saw good people doing atrocious things to sabotage that. And that really ... with me,” he said.

“I said a line in there, ‘I’ve seen the devil working behind the curtain and came back with some evidence,’ ” Killer Mike said, quoting a line from the song “2100.” “I saw what the DNC [Democratic National Committee] did, and it affected me in a way that I couldn’t make this record and not be darker on parts — because I felt more cynical.”

In “Talk to Me,” Killer Mike recounts his experience on the campaign trail by name-checking the Arabic word for Satan while seeming to critique Donald Trump: “Went to war with the devil and Shaytan / He wore a bad toupee and a spray tan.”

For his part, El-P has “Jaws” on his brain, but he seems to be talking not just about the shark but also America when he raps, “You’re gonna need a bigger boat, boys — you’re in trouble.”

On the album-closing “A Report to the Shareholders / Kill Your Masters,” he spits judgment on politicians: “Can’t contain the disdain for y’all demons / You talk clean and bomb hospitals / So I speak with the foulest mouth possible / And I drink like a Vulcan losing all faith in the logical.”

Across the hundreds of couplets, “RTJ3” references online surveillance, the police state, Chicago gangland and a power structure that earns profits despite the poverty surrounding them. “Good day from the house of the haunted — get a job, get a house, get a coffin,” El-P raps on “Don’t Get Captured.” “Don’t stray from the path, remain where you at — that maximizes our profit.”

That track begins a three-song suite that pocks the album with grimness, as though a new reality were sinking in. A sample from “The Twilight Zone” opens “Thieves”: “This is not a new world, it is simply an extension of what began in the old one.”

Asked about the darkness, El-P seemed torn. “Certainly, there are points,” he said, but “it doesn’t stay and it’ll never be the foundation of who we are.” Rather, he stressed that the primary goal remained “to just make raw … dope records and see where we can push each other and where our styles intertwine.”

Playfulness, in fact, abounds. In “Call Ticketron,” El-P revels in wordplay as he reassures Run the Jewels listeners that the “last two pirates alive are still yargin’ ” — but are living in a future where “the hovercraft’s cool but the air’s so putrid.”

“Everybody Stay Calm” features the rapper referencing “Willie Wonka”: “Oompa-Loompas, I’ll shoot a tune at ya medullas/ I’m cool as a rule but I’ll scalp a ruler.” El-P even wades into the 2016 meme centered on the spelling of the children’s series “Berenstain Bears.”

The result is a work that reconciles competing reflexes with an approach that El-P described as “a swagger, or way to perceive yourself, in the face of authority and in the face of the majority of the people. A way to have personal power based on an ethos and not based on your position in society.”

Eyeing the joint on the table, Killer Mike suggested taking a smoke break, and the two stood to make their way outside.

But first, El-P had one more thing to say: “If I see a king walking through the streets in all his regalia, I know that if I spit on him, all of the clothes and all the power doesn’t mean a … thing, because in that moment, me and him are the same. Am I right for doing it? I don’t ... know. But I’ll talk about the instinct.”

Twitter: @LilEdit

- Share via

Obama left the NEA vulnerable. Could Sylvester Stallone save it?

WHEN A COLLEAGUE SHARED a British tabloid report that Donald Trump was considering appointing a certain Sylvester Gardenzio Stallone as head of the National Endowment for the Arts we rolled our eyes, speechless.

Stallone has since said he would decline any offer for the top arts spot from Trump. Yet — and I can’t believe I am saying this — Sly Stallone may not have been such a bad idea for the NEA after all.

How fundamentally the world has turned in 2017.

Four years ago, when there was still hope that President Obama might turn out to be an arts leader, I had proposed that for his second term he eliminate the NEA altogether and instead create a Cabinet level department of culture, putting us on par with the rest of the world’s civilized countries. I further suggested as candidates the two most probing, visionary and persuasive artists and public intellectuals I could think of: the director Peter Sellars and Bard College President Leon Botstein.

Is Hollywood out of touch with your America? Tell us >>

There are many in Congress who would gladly eliminate the NEA to save an infinitesimal fraction of the federal budget (less than four-one hundredths of 1%, to be exact), replacing the NEA with nada.

There are many in Congress who would gladly eliminate the NEA to save an infinitesimal fraction of the federal budget (less than four-one hundredths of 1%, to be exact), replacing the NEA with nada. What the agency needs now more than vision is a fighter. A little star power wouldn’t hurt, either. Could Rocky save it?

Obama never promised to be an arts president. What candidate does? (Bernie Sanders did, but he is the only major one in recent memory). Still, there were indications early on that the Obama White House would prove to be a second Camelot, following the example of the arts-embracing Kennedys.

The mood for Obama’s first swearing in was classily set by classical musicians in 2009. Violinist Itzhak Perlman, cellist Yo-Yo Ma, clarinetist Anthony McGill and pianist Gabriella Montero warmed up the dignitaries with John Williams’ “Air and Simple Gifts,” written for the occasion. As with so much in Washington, a phony controversy ensued when it was learned that the quartet instrument-synced, but it was simply too cold to offer “Simple Gifts,” which required nimble fingers on strings and keys. That may have also been the start of giving Obama cold fingers when it came to the arts.

Even so, for their new home the Obamas borrowed from the National Gallery the most sophisticated art that had graced White House walls since Camelot. The first family occasionally showed up at the Kennedy Center or museums. The first lady hosted afternoon gatherings of musicians from different disciplines. We were told that the president was a reader of poetry.

The most promising sign of all was Obama’s unpretentious grace in the company of artists. He said the right things. We took it for granted that he supported the arts and understood their importance for the betterment of society. The vast majority of artists in America felt that Obama was on their side.

So we coasted. The president had to pick his fights, and the NEA, it turned out, was never to be one of them. In 2009, another phony controversy occurred when the far-right website Breitbart News reported that a spokesperson for the Obama administration had reputedly tried to politically influence artists. That pales next to President Reagan personally phoning up theater critic Dan Sullivan at The Times in 1981 to ask that he prop up Reagan’s old Hollywood pal Buddy Ebsen, whose new musical was a flop.

Ultimately, Obama appointed as NEA heads Broadway producer Rocco Landesman in his first term and arts executive Jane Chu in his second. Both proved personable promoters of the arts and the agency, treating their posts more as caretakers rather than visionaries. I used to regularly see a representative from the NEA at the Los Angeles Philharmonic during previous administrations when something particularly novel was presented. No more.

Still, the agency appeared to mean well. Its minuscule budget, always under $150 million a year, got divvied up to museums, performing arts groups, local education agencies and community projects as best it could. Landesman and Chu spent much of their time as arts activists, drumming up business.

But let’s get real. France’s federal arts budget rose last year to more than $4 billion! That’s $575 per person for the arts, as opposed to 45 cents per person in our country.

What this ultimately means is that while Obama valuably helped the mood of the arts in America, he did less for the arts infrastructure. He displayed considerably greater interest in pop culture and sports than in arts advocacy. He handed the Presidential Medal of Freedom to but a handful of noted and deserving artists — including architect Frank Gehry, painter Jasper Johns and Ma — whereas he picked a significantly larger number of Hollywood stars.

Mood, nonetheless, matters, and the vast majority of American artists are now worried about a Trump administration. We’ve heard the reports of the transition team struggling to find willing performers for the inauguration. According to Itay Hod of the Wrap, the Trump team has gone so far as offering ambassadorships to agents who can lasso a star, all to little avail. Operatic crooner Andrea Bocelli backed out, but the 16-year-old operatic crooner wannabe, Jackie Evancho, seems to be in. The Rockettes and Mormon Tabernacle Choir (minus members who are opting out or quitting in protest) thus far fill the insipid bill.

Meanwhile, artists who became complacent under Obama no longer are. President Lyndon Johnson did not decide against running for a second term because of a painting; Richard Nixon (who happened to support the NEA) did not resign as president offended by a symphony. But protest artists the likes of Leonard Bernstein, Bob Dylan, Robert Crumb and many others created a national temperament that helped change governments.

Antagonize the artists, and it may seem as though the world’s turning in 2017 will, in fact, be back to the late 1960s and early 1970s.

- Share via

Realism or cliche? Hollywood struggles to get the working class right

THE WORKING MAN IS BATTERED and bruised, celebrated and misunderstood. He is stoic and brash. He counts his hours and logs his years. He is the best and worst of us, as willing to walk into a coal mine as onto a battlefield. He endures until he breaks or accepts that the promises of manhood glimmered brighter when he was a boy.

The question now is how will Hollywood depict this working man — and working woman — in a culturally divisive era? What are the new narratives in a changing economy and racial strains driven by identity politics? Donald Trump’s election has refocused attention, much like the fall of the U.S. steel industry in the 1970s, on disillusioned and bitter parts of the country shaken by financial decline, foreign competition and addiction.

Is Hollywood out of touch with your America? Tell us >>

The Democratic Party, once the bastion of labor, has been accused of paying less attention to the white working class and focusing more on minorities and youth. Film and television creators are said to be too liberal and out of touch with the values and concerns of the heartland.

Yet as far removed as Hollywood seems from blue-collar realities, movies have for generations played on all manner of working men and women, taking us from steel mills to fishing trawlers, from textile plants to grocery check-out lines, and from one hard-pressed town to the next. Such portrayals cast the working class — from “The Grapes of Wrath” to “Harlan County, USA” — as indivisible from the success and failure of the American dream.

I grew up in a blue collar sentiment, but so often these people are stereotyped and mythologized in film. They come across as cliché.

— Scott Cooper, “Out of the Furnace” director

A number of movies have rendered insightful glimpses of working class and rural America that have risen above region and economic status to encompass the universal. These films have realized that stories — mainly about white, non-college-educated men and women — can veer as easily into stereotype and generalization as movies featuring minorities, transgenders and rock n’ roll bands. Even the best intentioned blue-collar tales can slip from sparse realism into stock masculinity and false redemption.

One of this year’s most evocative movies, “Hell or High Water,” follows two brothers, Toby and Tanner, across a West Texas landscape of foreclosures and ruin after the 2008 recession. The film has the style of an old western. But it is very much about how today’s capitalism is indifferent to families — at least 60% of Americans don’t have college educations — whose shrinking paychecks and diminished options leave them desperate amid fallow fields, pump jacks and frontier justice.

“I think the western is about people in harsh places trying to tame an unfriendly wilderness,” Chris Pine, who played Toby, told The Times. “Because life is defined by struggle, it’s kind of a perfect microcosmic experience to explore that. ‘Here we are, struggling.’ It’s about people persevering and persevering and persevering.”

Director David Mackenzie said the movie “felt to me like a snapshot of a nation.”

The trials, chores, joys, challenges, demons and dangers of the working class have been viewed through many prisms: Marlon Brando standing up to dockworker corruption in “On the Waterfront,” Sally Field fighting for a textile union in “Norma Rae,” Robert DeNiro and Christopher Walken leaving the steel plants of Pittsburgh to fight in Vietnam in “The Deer Hunter,” a labor leader demanding rights for migrant workers in “Cesar Chavez,” George Clooney and his doomed crew chasing fish in the North Atlantic in “The Perfect Storm,” coal miners rising against Pinkertons in bloody battles played out in John Sayles’ “Matewan” and this year’s “Paterson,” featuring Adam Driver as a poet-bus driver.

Such movies have an elegiac dignity at their core, respecting a man or woman’s honor and pride through the lens of their daily toil. A rigorous work ethic has long been one of the nation’s defining traits, deified not only in film but also in literature and music. Much of Bruce Springsteen’s playlist ruminates on accepting the working life with forbearance or escaping it with fuel-injected defiance. And on this plane, notably in movies, the working man is cast against the shadow of coal tipples, smokestacks, blast furnaces or other emblems of industry to suggest his ultimate fate is controlled by others.

“There’s been a lot of talk about the working class and the working man,” said director Kenneth Lonergan, whose “Manchester by the Sea” tells of the lives of a janitor and a fisherman. “But it’s all general. What are they talking about? A lot of people are out there fixing things. There’s a certain amount of sentimentalization when you get to movies.”

The film “Winter’s Bone,” which in large measure introduced Jennifer Lawrence to the world, slips into a sliver of the Ozarks in southwestern Missouri, where crime, clan and retribution trammel over a harsh, if beautiful, land that offers little prosperity. The working men and women here have turned into drug dealers and enforcers whose codes and moralities are challenged by Ree Dolly (Lawrence), a girl trying to save her home and family from the havoc caused by her methamphetamine-cooking father.

We’re a town of 14,000. Lost 1,200 jobs to Mexico in the last three years....That’s a brutal punch. The people I talked to just wanted to shake things up.

— Daniel Woodrell, “Winter’s Bone” author

Based on the novel of the same title by Daniel Woodrell, the film, directed by Debra Granik, is a dark glimpse at an often unnoticed part of the country. Like movies set in Appalachia or the Rust Belt, the story has a palpable sense of place and isolation. Woodrell, who lives in the Missouri region where his family has had roots since 1838, said in a recent interview that “the reason I stayed here so long is that I can walk two blocks and there’s the cemetery where my family is buried. A lot of resonance.”

He knows a number of people who voted for Trump. “We’re a town of 14,000. Lost 1,200 jobs to Mexico in the last three years that literally went to Mexico. That’s a brutal punch,” he said. “The people I talked to just wanted to shake things up. I’m a Democrat but I’m kind of nostalgic for the old Democrats who cared for the working class.”

Woodrell’s novels seek recesses both moral and geographical. They navigate sin, fallibility and the grays that make a life, adding force and richness to regional tales that echo far beyond their boundaries. “When any aspect of life gets focused on, it’d be really easy to make something grotesque if you focus on a narrow slice of it,” he said. “It’s not Mayberry and it’s not all ‘Winter’s Bone’... You try to make it human, respecting characters and taking them seriously. Show it from their point of view, not mine.”

The men in Scott Cooper’s evocatively photographed “Out of the Furnace” are forsaken and hard, living in Braddock, Pa., a steam-streaked steel town of crumbling houses, rail yards, dim taverns and the bones of an industry that once was. Two brothers — Russell (Christian Bale), a mill worker, and Rodney (Casey Affleck), a damaged Iraq war vet — live amid scoured ambitions that turn violent when Rodney takes up street fighting for money. These are men pushed to the brink by circumstance; a shrinking, battered family in a town of ghosts.

“You have to live there to know these people,” said Cooper, who was raised at the edge of the coal fields in Abingdon, Va. “I grew up in a blue collar sentiment but so often these people are stereotyped and mythologized in film. They come across as cliché.” He added that the suspicion and disillusionment in the Rust Belt, Appalachia and other regions “come from an ideological and cultural isolation from the rest of America. These are a group of people who see themselves as outsiders but they were really the backbone of America, especially in the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s. But lost jobs have led to lost pride and vices.”

Those vices have led to years of heroin and prescription drug addiction, early graves and a bitterness toward the government, which many blame for wage stagnation and jobs wiped out by foreign competition. It was this sense of desperation that drew many working class voters to Trump, a rich man who may not be one of them but who has vowed to rattle the establishment. For many, promises had been denied for too long in lands forgotten between New York and Los Angeles. As the working class continues to be redefined by automation and shifting demographics, it is this reality that Washington and Hollywood will be wrestling with for years to come.

“I wanted to treat it as honestly as I could,” Cooper said of his film. “The American dream is dead and it is not really coming back.”

On Twitter: @JeffreyLAT

“Manchester By The Sea” director Kenneth Lonergan talks about collaborating with Casey Affleck on the film, comparing him to a Columbo-like detective who investigates scenes.

- Share via

Rally white men. Demean women. Mock the impact of misogyny. How will Gamergate values play out in Trump’s America?

SEE IF THIS CAMPAIGN TACTIC sounds familiar: Rally white men who feel the world is changing too fast, leverage racial bias for the cause, and demean women along the way.

The strategy belonged to a radical corner of the gaming world that may have provided the winning playbook for the campaign that won the presidential election.

“Gamergate” is the term now used to describe the movement in which Internet trolls attacked high-profile people in the game industry if they attempted to change — or even speak out about — the misogynistic themes of video games. They are the gaming world’s radical right, and they’re fighting back against what they see as the onslaught of politically correct culture.

Now at least one of the people who provided a platform for the movement is headed for the White House.

Is Hollywood out of touch with your America? Tell us >>

Stephen K. Bannon oversaw the far-right Breitbart News, which published numerous articles about Gamergate, before becoming Donald Trump’s campaign chief executive. One report, from 2014, carried this headline: “Feminist bullies tearing the video game industry apart.” Today, Bannon is Trump’s pick for White House chief strategist and senior counselor.

The trajectories of Trump and Gamergate could be practically charted by the same graph — guys (for the most part) that a significant portion of the country didn’t take seriously pandered to humanity’s most base instincts and won. Entertainment and politics are becoming increasingly blurred. The president-elect, for instance, regularly tweets about “Saturday Night Live,” and nearly caused a culture war over “Hamilton.”

Entertainment and politics are becoming increasingly blurred. The president-elect, for instance, regularly tweets about ‘Saturday Night Live,’ and nearly caused a culture war over ‘Hamilton.’

Bannon once spoke favorably of Darth Vader, seemingly comparing himself to the “Star Wars” villain. Spoken like a strategist, or like someone pandering to his fans?

As Paul Booth, an associate professor at Chicago’s DePaul University who studies fan culture, put it: “You can look at the political race as a fan event.”

The term “Gamergate” emerged as a hashtag in mid-August 2014. It described the attacks, particularly on women in the gaming world, by trolls and eventually their de-facto leader Milo Yiannopoulos, who became Gamergate’s Breitbart champion.

The writer electrified his base in much the same way as did the Donald Trump campaign, arguing that the mainstream media and those with progressive thoughts simply failed to understand real gamers. “GamerGate,” he wrote, “has exposed both the feminist campaigners and even some gaming journalists as completely out of touch with the very reasons people play games.”

A sort of “drain the swamp” for the digitally connected.

Female game designers and journalists who spoke out about a more inclusive future for the medium were harassed on social media with threats of physical attacks, rape and death. Their emails were leaked (sound familiar?), and some saw details about their personal lives published online.

“Lock her up,” Trump supporters shouted about Hillary Clinton.

“I hope you die,” Gamergate champions tweeted at Anita Sarkeesian, a prominent cultural critic who critiques games from a feminist perspective.

One developer, Jennifer Hepler, author of “Women in Game Development: Breaking the Glass Level-Cap,” told The Times that she went so far as to install bulletproof glass on her windows after a lengthy online campaign against her. She was singled out for the inclusion of LGBT-friendly characters in a sword-and-sorcery game.

Gamergate advocates argued that gaming journalists were corrupt and were colluding to bring a politically correct makeover to the medium (read: take away our digital guns, treat women as something more than sex objects and cast someone — anyone — other than a white male as the lead protagonist).

Yiannopoulos, who has been banned from Twitter over allegations that he coordinated the sexist and racist harassment of “Ghostbusters” star Leslie Jones, galvanized his believers by claiming that gaming had come under attack by an “army of sociopathic feminist programmers and campaigners.”

Those who bought into his words targeted their ire at female critics who sought to intellectualize the medium. Ultimately, they were only bringing to light gaming’s more regrettable traits: that it has long pandered to a male-focused, gun-obsessed community where women were damsels more often than heroes.

Even Nintendo’s mobile title “Super Mario Run,” the biggest game of this winter, perpetuates the myth that women are to be rescued rather than kick butt.

The biggest, most visible games are still largely created by men for boys. Gamergate ultimately was driven by nostalgia and fear of change.

“Keep politics out of games,” was Gamergate proponents’ rallying cry, but they may as well have been saying, “Make games great again.”

There’s evidence that major developers are listening to their broader audience rather than being bullied by Gamergate, as recent titles such as “Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End,” “Watch Dogs 2” and “Dishonored 2” have touched on mature themes with a wide variety of characters.

Yet Gamergate brings to the fore some uncomfortable facts. The International Game Developers Assn. recently pegged the game industry at about 80% male, and while some surveys note that the game-playing community is close to a 50-50 male-female split, game consoles and gaming computers are still predominantly used by the male gamer.

Geoffrey Zatkin, co-founder of gaming consultancy Electronic Entertainment Design and Research, noted at a gaming event last March that North American gamers in 2015 leaned male 55% to 45%. But on home video game consoles, that number jumps to 60% male. On PCs, it’s even more heavily male at 64%.

For much of the last decade, the biggest game franchises — “Call of Duty” and “Grand Theft Auto” among them — were driven by guns and disparaging views of women and minorities. And unlike the Republican Party, the game industry has done this without lobbying money.

It may as well have been content unwittingly aimed directly at the so-called alt-right community, the loosely defined movement made up of social media-savvy white nationalists that has also attracted neo-Nazis, anti-Semites and misogynists.

Once again, there is a connection to Gamergate.

“The people who promoted Gamergate said they were concerned about journalism ethics,” read a post on PressThink, a site maintained by New York University professor Jay Rosen. “As a professor of journalism with a social media bent, I felt obligated to examine their claims. When I did I discovered nasty troll behavior with a hard edge of misogyny.”

Of course, Gamergaters were simply amplifying the content directed toward them — the rape jokes of “Grand Theft Auto,” the gun-fetishism of nearly every other game and a fantasy vision of the world ruled almost exclusively by white men.

So Hollywood isn’t out of touch with the real — make that conservative — America, after all. The entertainment powerhouses behind the world’s biggest games have directly targeted it. And now the rest of the country — the majority of voters behind the popular vote, if you will — can’t press the jump button to avoid it.

Twitter: @Toddmartens

- Share via

Exploiting fear of Muslims? The far right has nothing on liberal Hollywood

LONG BEFORE DONALD TRUMP campaigned on the promise of banning Muslims from entering the U.S. or creating a registry for those who already live here, there was a master fear monger who made the president-elect’s divisive rhetoric seem like child’s play.

It capitalized upon the terror of 9/11 by portraying most Muslims (even those who are American) as terrorists, cast a suspicious eye toward anyone who looked remotely like Sallah from “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” and pretty much ensured that Westerners would know Islam through only the prism of suicide bombings, religious extremism and oppressed women in burkas.

When it comes to exploiting fear of the other for personal gain, the far right has nothing on liberal Hollywood.

Is Hollywood out of touch with your America? Tell us >>

Television producers, writers, actors and network execs — many of whom have openly criticized ultra-conservative politicians for their intolerant views — have done more to popularize Islamophobia over the last 15 years than all of Trump’s campaign proclamations.

“There has never been liberal Hollywood when it comes to the portrayal of Muslims on TV,” says professor and author Jack Shaheen, who’s been researching the subject since the mid 1970s and served as a cultural consultant on films such as “Three Kings” and “Syriana.” “They’ve reinforced the idea that many Americans now have — that all Muslims are terrorists. They knew they could get away with it because no one was going to protest. They’ve been playing to the balcony, and in doing so, they’ve been getting the ratings.”

That dynamic grew exponentially following the 9/11 attacks: While President George W. Bush delivered dozens of speeches about how ours was not a war against Islam but “a campaign against evil,” network television was busy putting the finishing touches on the series that came to embody TV’s narrative about our war against evil Islam.

Eight weeks after the attacks, Fox released “24,” a series steeped in scheming, swarthy Muslims and the heroic efforts of a very non-swarthy Jack Bauer (Kiefer Sutherland).The series outlasted both of Bush’s terms and spawned an army of like-minded shows.

The next phase in television terrorism drama included Showtime’s “Sleeper Cell,” which arrived with the tagline “Friends. Neighbors. Husbands. Terrorists,” and “Homeland,” where the mere act of a man praying toward Mecca signaled foreboding events. And with a title like “Tyrant,” it was clear that FX’s drama about an American Arab family was no “Cosby Show.”

Even network TV’s good Muslims like Sayid on “Lost” or twins *Nimah and Raina of “Quantico” are defined by a connection to Saddam’s Republican Guard or terror groups.

“It’s like the LGBT community 30 years ago,” says Sue Obeidi, director of the civil rights advocacy group the Muslim Public Affairs Council, Hollywood bureau. “Every time there was a gay character on TV or in film, the story line would be about AIDS. Almost all Muslim story lines up to now are connected to terror. Even if they end up being a good person, it’s often discovered under a cloud of suspicion.”

There is no doubt that homegrown terror attacks in the U.S. — from San Bernardino to Orlando — have helped bolster arguments that art is only reflecting reality. But as University of North Carolina professor Charles Kurzman and David Schanzer, Duke University professor and director of the Triangle Center on Terrorism and Homeland Security, wrote in a 2015 research paper, “Law enforcement agencies in the United States consider anti-government violent extremists, not radicalized Muslims, to be the most severe threat of political violence that they face.”

Television of late has been trying to adjust to a changing world by developing more diverse narratives and investing in more projects by creators and writers of color, including Shonda Rhimes (“Scandal”), Kenya Barris (“blackish”) and Nahnatchka Khan (“Fresh Off the Boat”). But despite the number of shows that have Islamic terror elements in their plots — from “Madam Secretary” to “CSI” — Muslims behind the camera are still rare.

There has never been liberal Hollywood when it comes to the portrayal of Muslims on TV.

— Jack Shaheen, professor and author

That lack of representation was glaringly evident in the fifth season of “Homeland,” when graffiti that read “‘Homeland’ is racist” in Arabic made it into a scene. Artists hired to decorate the wall of the fictional Syrian refugee camp slipped the words in, and there was no one else on set with enough knowledge of the Arab world to catch their subversive message.

“Hollywood is not necessarily biased toward a particular political view, but it is biased toward what does and doesn’t make money,” says author Reza Aslan, who recently co-created an ABC pilot for a comedy about an American Muslim family in the age of Trump. “Since 9/11, the market wanted these almost comic book characterizations of Muslims as the bad guy. But that market has dried up. It’s not interesting anymore. They want different narratives about Muslims and Middle Easterners, and networks are looking for ways to do that.”

Characters who arrived during the seemingly endless presidential campaign of the last year and a half have definitely signaled a shift.

In HBO’s critically lauded “The Night Of,” we met Nasir Khan (Riz Ahmed), an average college student accused of a crime that had nothing to do with terrorism; his journey through the legal system highlighted an institutional prejudice.

Government can protect our rights as citizens, or maybe with Trump it won’t, but it’s really TV and film that changes the way people feel about one another.

— Sue Obeidi, director of the Muslim Public Affairs Council, Hollywood bureau

Aziz Ansari’s Netflix series, “Master of None,” depicts him as a struggling actor who finds himself in all sorts of painfully normal situations — bad dates, flubbed job interviews, disappointing his immigrant parents — situations far too commonplace for TV’s Muslims before him. “If we don’t do it, who else is going to do it?” Ansari said, explaining why he created the show.

Yet in an unforeseen twist, Trump’s election has potentially accelerated the interest in more nuanced story lines involving actors like Ansari.

“Right after the election — I’m talking the day or two days after — we had people in the industry reach out to us: the USA Network, Amazon, Hulu, a major network,” says civil rights advocate Obeidi. “They have directives from their networks to watch for Islamophobic tones. Not that the studios were giving directives for Islamophobic story lines before, but now they’re saying, ‘We need consultants because our studio wants to be careful of certain red lines.’ That’s all new.”

The recent presidential election is such an extraordinary moment in American history, says Aslan, that there’s a new drive among the network and studio executives he’s met with to create a counter narrative to Trump’s.

“They want to make a statement about American ideals and the people who make this country what it is, whether that is focusing on minority groups, African American, Muslims, Jews, or whether it’s just simply presenting a different side of the American story,” Aslan says. “But I can say with absolute confidence the industry has been galvanized by this election.”

And whether you believe it or not, television is the frontline of shaping public perception. Even when it comes to depicting the oh-so-mysterious Muslim.

“It’s pop culture that’s going to change opinions about how people feel about one another,” says Obeidi. “Government can protect our rights as citizens — or maybe now with Trump it won’t — but it’s really TV and film that changes the way people feel about one another.”

On Twitter: @LorraineAli

-----------------------

FOR THE RECORD

*In an earlier version of this story, the “Quantico” character Alex was described as Muslim. The character is not Muslim. The series characters Raina and Nimah are Muslim.

- Share via

‘The Middle’ offers something rare on TV, a candid look at the anxiety of a working family

IN FALL 2009, BARELY A YEAR into the Great Recession, two new family sitcoms aired back-to-back on Wednesday nights: “The Middle” and “Modern Family.”

Filmed in a quasi-mockumentary style, “Modern Family” followed three affluent, interrelated families in suburban Los Angeles, including a gay couple with an adopted daughter from Vietnam. Praised for its diversity, it was instantly anointed the best new sitcom on television, became a ratings smash for ABC and has been nominated for 77 Emmys.

Is Hollywood out of touch with your America? Tell us >>

At least superficially, “The Middle” was less groundbreaking. Created by DeAnn Heline and Eileen Heisler, it centered on the Hecks, an intentionally unremarkable lower-middle-class family living in the small town of Orson, Ind., proud home of the world’s largest polyurethane cow.

Dad Mike (Neil Flynn) is a taciturn quarry manager who later launches a diaper business. Mom Frankie (Patricia Heaton) sells cars — or tries to — before studying to become a dental hygienist. They have three kids who aren’t particularly bright, cool or attractive, epitomized by middle child Sue (played by the exceptional Eden Sher), whose most distinctive trait is her insistence on never giving up, despite being pretty bad at most things she tries.

The series revolves around the Hecks’ near-constant efforts to fix various broken appliances and put (sometimes recently expired) food on the table. It may not have shifted public opinion on same-sex marriage, but in its unassuming way, “The Middle” has been every bit as revelatory as “Modern Family.” Over eight seasons, it has portrayed the economic anxieties of working families with a candor rarely glimpsed on American broadcast television, which has aspiration encoded in its DNA.

Though several of ABC’s family sitcoms deal with class more fleetingly, ‘The Middle’ is arguably the only long-running comedy on broadcast television that puts the subject front and center.

Though several of ABC’s family sitcoms deal with class more fleetingly, “The Middle” is arguably the only long-running comedy on broadcast television that puts the subject front and center. That it also happens to be set in “one of those places you fly over on your way from somewhere to somewhere else,” as Frankie says in the pilot’s opening narration, rather than a cosmopolitan city or well-heeled suburb, makes it a double rarity.

And though “The Middle” is a pleasantly apolitical show, it happens to portray the kind of working-class, Rust Belt voters who in real life helped propel Donald Trump to victory in November. (It also stars Heaton, one of Hollywood’s more prominent conservatives.)

If, as conventional wisdom dictates, the Washington establishment has ignored this demographic for too long, then so has Hollywood — especially television, which has made enormous strides in representations of race and sexuality but still portrays bourgeois, upper-middle-class coastal dwellers as the default norm.

Heline and Heisler began developing the idea for “The Middle” about a decade ago, around the time they were writing “Lipstick Jungle,” a “Sex and the City”-esque dramedy about high-powered New York City women.

As native Midwesterners turned Angelenos, Heline and Heisler longed to do a show about the world in which they grew up, where “when something goes wrong, your neighbor brings you a casserole,” Heline recalled in a recent interview.

After a number of delays, “The Middle” made it to air at a time when virtually everyone in America was feeling the pinch financially. “I think in some ways it helped our show,” Heline said, “because it felt more relevant.”

In the show’s early days, ABC would occasionally give notes along the lines of “try not to make it too depressing,” but Heline and Heisler, who grew up in the Midwest in circumstances similar to the Hecks’, were determined to treat these people with honor.

Refreshingly, “The Middle” neither venerates the Hecks as “real Americans,” nor ridicules them as flyover rubes.

“The Middle” even looks different from most sitcoms. Instead of tasteful Pottery Barn throw pillows and gleaming stainless-steel kitchens, the Hecks’ house is furnished haphazardly, cluttered with neglected piles of mail and laundry. Marie Kondo would most definitely not approve.

While no one would ever mistake “The Middle” for John Steinbeck, its willingness to acknowledge the constant precariousness of the Hecks’ finances makes it quietly revolutionary.

In a standout Season 2 episode called “The Big Chill,” Mike gives Frankie the silent treatment after she accidentally spends $200 on a tube of eye cream and eats up their household budget.

“I’m not mad that you made a mistake. I’m mad because we can’t afford to make a mistake,” Mike eventually explains to his wife. “You think I like it ... that at this point in our lives, we have to have four jobs just to stay poor?”

Now in its eighth season, a time when many long-running sitcoms resort to Cousin Oliver-esque gimmicks in a desperate bid to keep things fresh, “The Middle” continues to find new ways for the Hecks to just barely get by.

In a recent episode, Sue discovers she isn’t enrolled at college because her family failed to file her financial aid paperwork in time. Mike sells his diaper business in order to pay her tuition.

Heline and Heisler cut their teeth on “Roseanne,” TV’s last great blue-collar hit. The experience taught them that authenticity could be funny. “When we created ‘The Middle,’ that’s what we wanted to go back to,” Heline said. “We felt like the networks had abandoned that.”

With a few exceptions — most notably, the work of producer Norman Lear in the 1970s — American television has always been squeamish about acknowledging class because it “goes against the notion of the American dream,” says Anthony Harkins, a professor at Western Kentucky University whose research focuses on pop culture depictions of Middle America. “It doesn’t put you in a buying mood.”

The booming ‘80s ushered in an obsession with yuppies and one-percenters, in shows such as “Dynasty,” “Thirtysomething” and “Diff’rent Strokes.” “The Cosby Show” broke new racial barriers, but money was rarely a concern for the Huxtables.

Then came “Roseanne,” which premiered during the waning days of the Reagan administration in fall 1988. The sitcom about a brash Illinois factory worker, her underemployed husband and their unruly children was one of the top-rated shows on television for most of its nine-season run.

Astonishingly, however, it was never even nominated for a comedy series Emmy. (Then, as now, Television Academy voters preferred shows about affluent urbanites, such as “Murphy Brown” and “Frasier.”)

In the two decades since “Roseanne” went off the air, there have been other shows set in small-town, blue-collar America. But they have tended to be niche shows along the lines of “Friday Night Lights” or “Raising Hope,” championed by critics and other “coastal elites” but ignored by the rest of the country.

“The Middle” has never been a Nielsen blockbuster, but it has been a steady performer for ABC. It now runs almost even with “Modern Family” in the ratings and is regularly cited as one of TV’s most underrated shows. If the TV Academy remains immune to its charms, Heline and Heisler maintain a very Midwestern attitude.

“We’re not the type to demand attention,” Heline said. “We’ll just keep our head down and keep doing what we do.”

Twitter: @MeredithBlake

- Share via

These films capture the real world’s ambivalence to women in power

EARLY ON IN THE GERMAN comedy “Toni Erdmann,” Ines Conradi (Sandra Hüller), a consultant for a Romanian oil giant called Dacoil, goes out with her clients for drinks. When asked about her work, she mentions her role overseeing the company’s imminent outsourcing plan — a faux pas that rattles Dacoil’s chief executive, who peevishly corrects her in front of everyone.