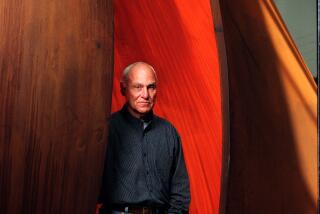

Richard Hunt, renowned sculptor of public art, inspired by the civil rights movement, dies at 88

- Share via

Richard Hunt, a prolific sculptor who was influenced by the civil rights movement and whose public art can be seen across the United States, has died. He was 88.

Hunt died Saturday at his home in his native Chicago , according to a statement on Hunt’s website, which called him “one of the most important sculptors this nation has produced.” No cause of death was listed.

Throughout his career, which spanned 70 years, Hunt completed more than 160 public sculpture commissions across 24 states and Washington, D.C., including well-known works at Howard University, a monument to journalist and civil rights activist Ida B. Wells in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood, completed in 2021, and his sculpture “Book Bird,” which will sit outside the upcoming Obama Presidential Center, also in Chicago.

Steve Roden, a multidisciplinary artist who produced abstract work in painting, sculpture, sound, installation and video, died at home in Pasadena on Wednesday.

“It will be an inspiration for visitors from around the world, and an enduring reminder of a remarkable man,” former President Obama said in a statement Sunday, calling Hunt “one of the finest artists ever to come out of Chicago.”

Hunt had more than 150 solo exhibitions, and his work can be found in more than 100 public museums across the globe. In Los Angeles, his 1975 work “Extended Forms” was acquired by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1980, and his “Why” sits in the Hammer Museum’s Franklin D. Murphy Sculpture Garden on the UCLA campus.

“There are a range of possibilities for art on public buildings or in public places to commemorate, to inspire,” Hunt said last year, referring to his work for the Obama library. “Art can enliven and set certain standards for what’s going on in and around it and within the community.”

Fernando Botero, whose depictions of people and objects in plump, exaggerated forms became emblems of Colombian art around the world, has died. He was 91.

Born Sept. 12, 1935, on Chicago’s South Side, Hunt was 19 when he went to the open-casket funeral of Emmett Till, a Black teenager from Chicago who was brutally killed and lynched in Mississippi by white assailants. Hunt later said the experience in 1955 influenced his artistic work and a commitment to civil rights.

A self-taught welder, Hunt often used found metal materials, such as car bumpers, in his work. Just a few years after Till’s funeral, Hunt gained national recognition when the Museum of Modern Art in New York acquired his sculpture “Arachne.”

Hunt was drawn to abstractions and was influenced by the works of Julio González, Pablo Picasso, David Smith and Alberto Giacometti, as well as his own extensive African art collection.

The investigation into the lynching of Black teenager Emmett Till in Mississippi nearly 70 years ago ended as it began, with a mystery that might never be solved.

Hunt was a graduate of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1968, then-President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed him to the National Council on the Arts. Three years later, he was the first Black sculptor to have a solo retrospective exhibition at MoMa.

A piece Hunt recently completed to honor Till, called “Hero Ascending,” is expected to be installed at Till’s childhood home in Chicago next year.

At times, Hunt would differentiate himself from his Black artistic contemporaries of the 1960s and ’70s who worked to build an overt Black aesthetic. In a 1985 interview with artist, art historian and media personality Richard Love, he described his work as “being symbolic of ideas or themes, but not dealing with subject matter in a very literal way.”

“I’ve tended to be commissioned by people who look at my work as what it is,” he said.

Even so, his abstract style was rooted in his knowledge of a specific subject, especially when dealing with commissioned work around historical figures. In an interview with the Chicago Tribune in 2023, Hunt described his inspiration for a piece as something that “comes forward to me as I’m working on it.”

Director Sam Pollard’s film overflows with the work of top African American visual artists working today.

His biographer, Jon Ott, noted that that inspiration was a product of intense study, including “deep, deep readings.”

“When he was doing the Ida B. Wells, I’d come visit Richard and he’d have a stack of seven different books on Ida B. Wells — lynching, photographs and history,” Ott said. “It’s the same thing with Emmett Till. If you were at his apartment, he’s got a stack of books on Emmett Till and things because he’s working on that piece. He’s in the moment but he has all that history in his head while his hands are touching the metal.”

Although much of his work was commissioned, Hunt said creative independence was always paramount.

“I am interested more than anything else in being a free person,” he once said, according to his website. “To me, that means that I can make what I want to make, regardless of what anyone else thinks I should make.”

Hunt is survived by his daughter, Cecilia, and his sister, Marian.

A private funeral service is planned in Chicago. A public celebration of his life and art will be held next year, according to his website.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.