Details of Emmett Till killing still a mystery as probe ends

- Share via

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. — The investigation into the lynching of Black teenager Emmett Till nearly 70 years ago ended as it began, with a mystery that might never be solved. All these decades later, it’s still not even clear whether the gruesome homicide was the work of a pair of racist brutes or a larger group of conspirators.

Two white men publicly confessed to the slaying after being acquitted by an all-white jury in Mississippi in 1955, but a Justice Department report released last week said at least one more, unnamed person was involved in Till’s abduction. Experts who have studied the case believe others participated, from a half-dozen to more than 14.

The lack of answers to decades-old, nagging questions has created a void for Till’s family. Thelma Wright Edwards, a relative who recalled putting diapers on Till as a child, talked about the emptiness left by the decision to end what will probably be the final investigation into his death.

“Nothing was settled. The case is closed, and we have to go on from here,” she told a news conference in Chicago.

In a sense, the nation as a whole was denied a proper ending to an awful tale because the true story of one of the most infamous hate crimes of the last century may never be known.

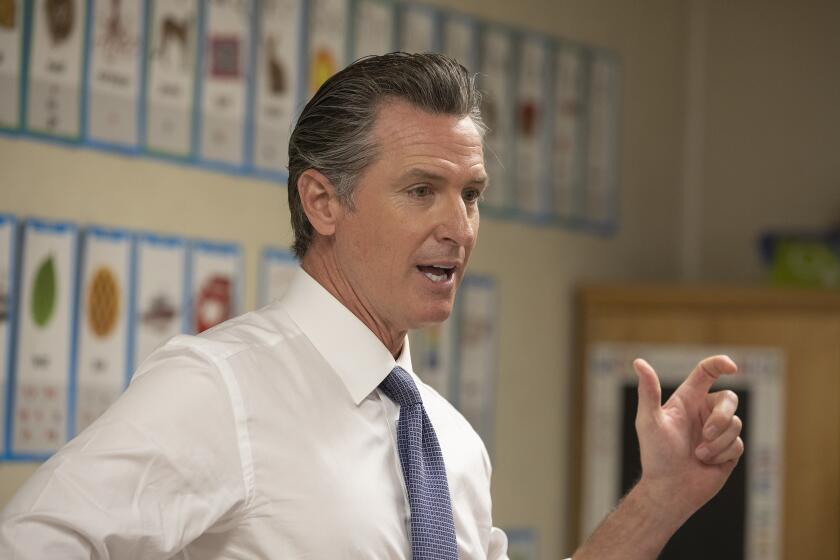

The proposed law would let California citizens sue gun manufacturers, similar to how Texas has made it easier for its residents to sue abortion providers.

“On abstract levels, truth has been lost and justice has been lost. The complexity of what happened has been lost,” said Dave Tell, a professor at the University of Kansas who wrote “Remembering Emmett Till.”

Till, who was 14 and from Chicago, went to Mississippi to visit relatives during the summer of 1955. On Aug. 24, witnesses said he whistled at a white woman in a rural grocery store, a violation of the South’s racist societal codes at the time. In return, he was rousted from bed and abducted from a great-uncle’s home in the predawn hours four days later.

With relatives uncertain over the teen’s whereabouts and fearing the worst, Till’s body — weighted down with a large fan from a cotton gin — was pulled from the Tallahatchie River three days later. Roy Bryant, whose then-wife, Carolyn, was the subject of Till’s alleged whistle, and Roy Bryant’s half brother, J.W. Milam, were charged with murder and on trial before an all-white jury within two weeks.

From the beginning, prosecutors portrayed the lynching as the work of a group, said David Beito, a retired University of Alabama professor and author who researched the case.

“Their official argument was that this beating occurred and that more than two people were involved. They argued a conspiracy, in effect,” Beito said.

Although only Bryant and Milam were charged, Black teenager Willie Reed testified during their trial that he saw a group of white men and Black men in a truck with a person he later realized was Till based upon photos. Till’s great-uncle testified that Bryant and Milam were accompanied by a third person with a voice “lighter” than a man’s when they abducted Till, indicating the possible presence of a woman.

Acquitted of killing Till and no longer in legal jeopardy, Bryant and Milam were paid to do an interview for Look magazine in which they admitted killing Till and suggested they were honor-bound as white Southerners to take vengeance on a disrespectful Black boy who affronted Bryant’s wife.

With the magazine’s wide circulation at the time, the Look article reset the narrative reported in the Black press of a group killing, Tell said.

“For that period of about five months, there was a pretty widespread consensus that there were five white men involved and two African Americans. I feel pretty comfortable saying that,” Tell said. “I think that’s what happened.”

Milam’s relative Leslie Milam bolstered the idea that a group of people was involved in a deathbed confession years later to being involved in the lynching, Beito said. Several Black men were suggested through the years as having helped restrain Till in the back of a truck while their boss and other white men rode in the cab, he said.

“[The Black men] were under duress. They didn’t have a choice,” Tell said.

Keith Beauchamp, a filmmaker who investigated the case for his documentary “The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till,” said as many as 14 white and Black people were involved with the abduction, killing and cleanup.

Through it all, no one else was ever charged, and the narrative of exactly what happened remains murky. One after the other, all possible suspects died, save one.

A Mississippi grand jury declined in 2007 to indict Carolyn Bryant Donham, Bryant’s onetime wife who is now in her 80s. The Justice Department reopened the investigation after a 2017 book quoted Donham as saying she lied when she claimed Till grabbed her, whistled and made sexual advances. But the investigation found no basis to charge her over the author’s claim that she recanted her statements from 1955. Donham denied changing her story, the Justice Department report said.

The Rev. Wheeler Parker Jr., a cousin who was with Till at the store and in the house the night he was abducted, expressed disappointment over the lack of justice and paucity of answers after decades of review. Parker said he heard his cousin whistle, but that was all that happened.

“We can’t bring him back, but we can carry on and let America know we need to know the truth, and that’s what we look for,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.