Review: Two rewarding MOCA permanent collection exhibits map L.A. art — and the museum’s limits

- Share via

In 1976, when he was 30, David Lamelas moved to Los Angeles. Born and raised in Buenos Aires, and educated there at the National Academy of Fine Arts and in London at St. Martin’s School of Art, he knew virtually no one in Southern California. So, once he settled in, he began to invite artists to his Hollywood studio to sit for a portrait drawing, expanding his pool of new acquaintances by word-of-mouth.

Art was the mechanism to build a web of relationships. The result is one fulcrum for “Mapping an Art World: Los Angeles in the 1970s and 1980s,” a show that is one of two rewarding current exhibitions drawn from the celebrated permanent collection at the Museum of Contemporary Art. The two will fill all its galleries until spring.

MOCA has nearly 7,000 works in its collection, and questions multiply around how to organize selections for their display. “Mapping” takes an unusual but engaging route, using social relationships among artists, rather than styles or subjects found in their art.

Those relationships include having once had in common a studio neighborhood (the Westside), gallery representation (Brockman Gallery in Leimert Park), a private collection (Panza), a growing public collection (the Lannan Foundation), school mates and faculty (at CalArts) and more. Each of those gets a gallery where very different works by very different artists cohabit.

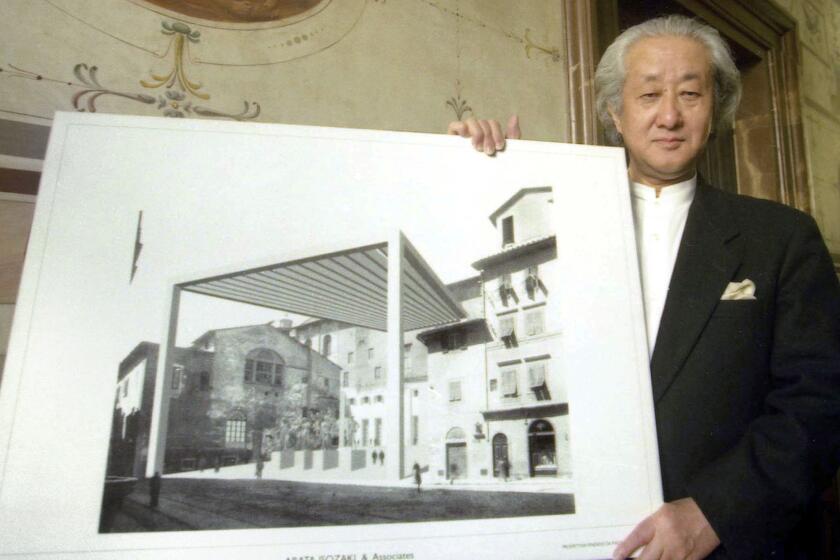

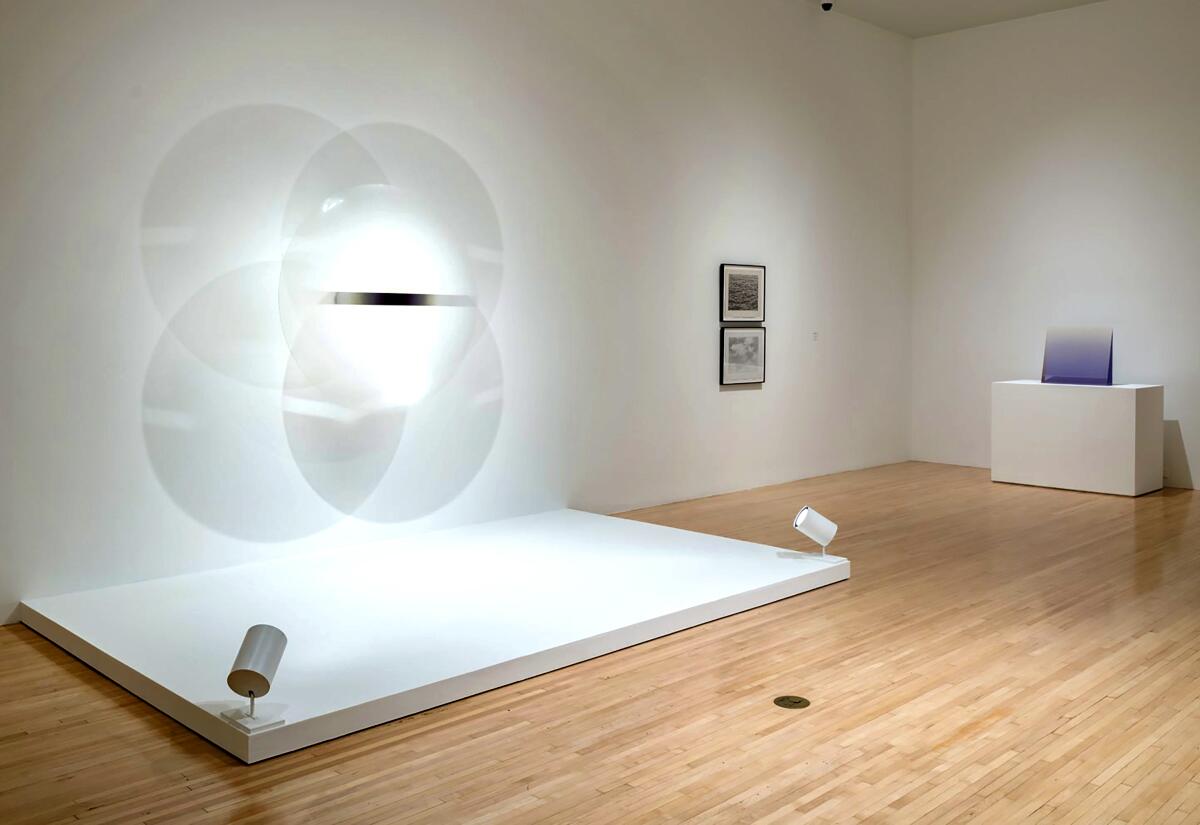

The relationship examples from the period are not comprehensive — other collections and art schools could be charted, for example — but they are effective in evoking the social complexity of art’s private production and public consumption. They lead to the 1979 establishment and 1986 formal opening of MOCA itself. The penultimate gallery displays the Grand Avenue building designs by Japanese architect Arata Isozaki, who died last December at 91, while the survey concludes with work by eight of the 16 influential members of the Artists Advisory Council, including Robert Irwin and Vija Celmins, who helped get the place off the ground.

The architect, who died this week at the age of 91, had to contend with a wildly complicated site — and L.A.’s bare-knuckle patronage.

Lots of great art was made in Los Angeles after the end of World War II. MOCA represented something wholly new: the beginning of L.A. art’s full-scale institutionalization.

An anticipation of that inevitable development flickers in the 1976 Lamelas installation.

Forty drawings are displayed in an organized grid, eight across and five down, like a formal genealogy or maybe a corporate flow chart. All are also cast on the adjacent wall by slides from an old-fashioned whirring projector, one by one. (The slide projector jammed twice during my visit, as technology old or new often does.) Straightforward to the point of being business-like, the quotidian portrait drawings are not what you might call penetrating, stirring or dynamic, and they don’t come close to prompting the usual clichés about an artist revealing a subject’s deeper inner life.

Instead, everything sits on the surface. Each slide of a portrait bust is followed by a title card with the sitter’s name, some now famous and some obscure, plus their place of residence within L.A.’s vast suburban sprawl. A kind of makeshift silent movie crossed with the materials of a school’s lecture hall, it’s more “Dragnet’s” Sgt. Joe Friday — “Just the facts, ma’am” — than the extravagant portrait fictions of Rembrandt and Frida Kahlo or the intense refinement and sophistication of Don Bachardy.

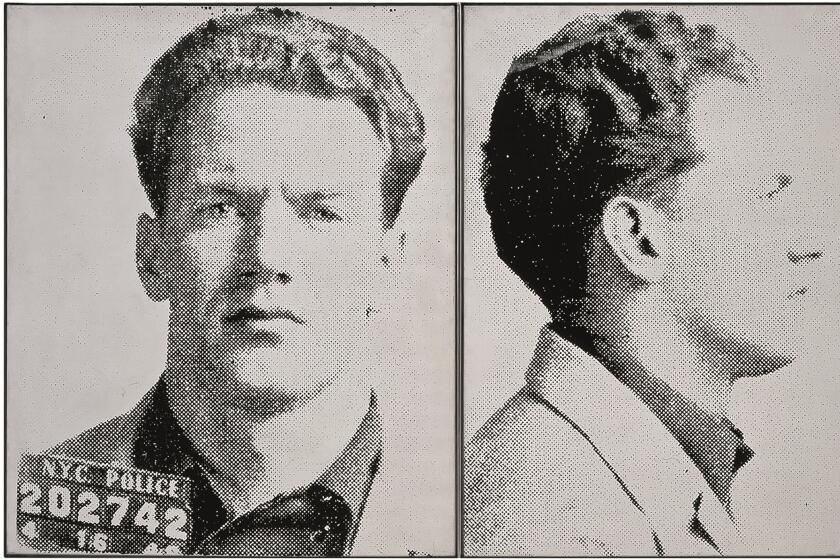

Andy Warhol’s disastrous 1964 mug shot mural was most certainly political, like Donald Trump’s recently released booking photo.

Having your portrait done is a profoundly personal, sometimes uncomfortable experience, as an artist unrelentingly scrutinizes your appearance. Sometimes conversation ensues. What makes the Lamelas display unexpectedly captivating is that it withholds every shred of that personal interaction save for one: looking. Titled “Los Angeles Friends (Larger Than Life),” the installation slyly manages to index relationships, which has the surprising effect of being inviting.

You think, “I could be part of that.”

In a way, that’s the ultimate subject of “Mapping an Art World,” which offers an intriguing curatorial structure for considering the post-1960s emergence of Los Angeles as a profound art center. There’s a modest, nonhierarchical quality to the presentation, and it avoids the usual corny ruminations on L.A. aesthetic clichés like sunshine-and-noir or the Dream Factory.

Object labeling is down to earth and informative, but a few installation missteps have been made. Floor sculptures such as an oozing Lynda Benglis “blob” of poured polyurethane foam or Mike Kelley’s black funerary boxes for burial of childhood stuffed toys should be on very low pedestals to assuage security concerns, not corralled inside clumsy wire stanchions. But those flubs are minor.

The show represents the MOCA debut of chief curator Clara Kim, appointed last year, along with museum colleagues Rebecca Lowery and Emilia Nicholson-Fajardo. The second exhibition, “Long Story Short,” was organized by the museum’s Anna Katz and Paula Kroll.

The trimmed story it tells unfolds slowly — and almost surreptitiously.

The first room houses some of the museum’s greatest knockout treasures, such as the 1949 Jackson Pollock drip painting “Number 1” and Robert Rauschenberg’s 1957 “Factum I” and “Factum II,” the almost-but-not-quite matched set of nearly identical, collaged Expressionist canvases. Enter the second gallery, where rigorous geometric abstract paintings by Bridget Riley, Billy Al Bengston, Jo Baer and Mary Corse and a sculpture by Larry Bell hold sway, and suddenly the prior room’s limitations are framed: There, only one of the 13 works was by a woman, painter Lee Krasner, and only one was by a non-New Yorker, painter Robert Colescott, who was also the only nonwhite artist. Room two expands West and East, to L.A. and Europe.

The third room sets the terms for what will follow. A gallery-filling architectural sculpture transforms a Midwestern “Back Porch With Picnic Table” into a poetic abstraction. Siah Armajani, the Iranian expatriate to Minnesota, who died at 81 in 2020, built a homespun Cubist meditation on confinement and liberation out of windows, doors, benches and stairs. Armajani left Tehran in 1960 in response to intolerably growing human rights restrictions, and his sheltering sculpture, with its juxtaposition of slippery stairs to nowhere, fractured rooms and comforting communal table, gives vernacular physical form to contradictions built into the promises of American democracy.

The next six galleries are constructed from an unequivocal curatorial commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion, featuring a broad array of engaging works by artists who identify as Black, queer, AAPI, white, Latino, straight and more. More than half are works by women, an accurate reflection of working artists in the art world. The exhibition warrant is not touted in any wall texts, either exhorting or self-congratulatory; it’s just done.

This only matters, of course, if the artists and the chosen examples are good. Most are. Take these two.

Zoe Leonard’s blistering 1992 typescript, “I want a president,” is timely and prescient. The text, all typed on a single, fragile, slightly rumpled sheet of onionskin paper, begins, “I want a dyke for president. I want a person with aids for president. I want a fag for vice president and I want someone with no health insurance and I want someone who grew up in a place where the earth is so saturated with toxic waste that they didn’t have a choice about getting leukemia.”

It continues on in that insistent vein of asserting art as an expression of human desire — some socially forbidden, some alienated, some available — for several hundred words. That typewriters were on the way out in 1992 lends an elegiac quality to her fury about life during the enervated presidency of plutocrat George H.W. Bush, as HIV infection became the leading cause of death among young men and in particular Black men.

Across the room, two large and lovely 2014 landscape photographs by Ken Gonzales-Day record trees where two among more than 350 California lynchings, a third of them murdering Latinos, took place between 1850 statehood and 1935. Gonzales-Day’s art is the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. A gnarled and withered tree set against verdant green hills and a lush and leafy one amid parched golden fields both look like paradise. The tension between what you know about these two places and what you see of them conjures an unsettling landscape filled with ghosts.

Social justice is a cultural watchword today. These and other works demonstrate how the subject has been so for generations of artists.

On the way out, four HEPA air purifiers quietly hum just before a lineup of a dozen 1978 portrait photographs shot in East Los Angeles by John Valadez — an archive the artist made amid swirling hysteria over Latino immigration that today simply reflects a prior generation of the city’s current near-majority population. The purifiers are a sly and witty 2020 installation sculpture by Carolyn Lazard. Inside the pristine white cube of the art museum, Lazard’s art is calmly removing unseen pollutants.

A question: Is the selection of artists, especially in “Mapping an Art World,” fully representative of the period’s history? Simple answer: No. Museum permanent collections never are. There are always limits, which always need addressing.

At MOCA, a big one is limited exhibition space. Having enjoyed both shows, I also couldn’t help regretting what remains in collection storage. An obvious example: Despite 11 critically important Rauschenberg combine paintings, a staggering group unrivaled at any museum anywhere in the world, nine are not on view. They haven’t all been shown together for years. Exhibition space for the permanent collection is inadequate.

That deficiency exists elsewhere in institutionalized L.A. The Hammer Museum opened its refurbished building with zero dedicated space for any of its contemporary collection, which numbers 4,000 works. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art is spending upwards of three-quarters of a billion dollars constructing 110,000 square feet of new galleries for an encyclopedic permanent collection, replacing 127,000 square feet in buildings it recently tore down. Storerooms at the Fowler Museum are bulging. And more.

MOCA, which has grown by leaps and bounds in the past four decades, is the same physical size now as it was when the Grand Avenue branch opened its doors in 1986. That’s an acute problem that needs fixing. The two collection exhibitions, both with unusually long runs not ending until March and May of next year, are engrossing; but they also rouse an unfulfilled appetite for something nominally more permanent.

“Mapping an Art World” and "Long Story Short"

Where: MOCA, 250 S. Grand Ave., Los Angeles

When: “Mapping an Art World” through March 10; “Long Story Short” through May 5. 11 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Fridays, 11 a.m.-8 p.m. Thursdays, 11 a.m.-6 p.m Saturdays-Sundays.

Info: (213) 626-6222, moca.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.