Review: Wit and fury merge in Judith Bernstein’s new paintings that scream ‘Snap out of it’

- Share via

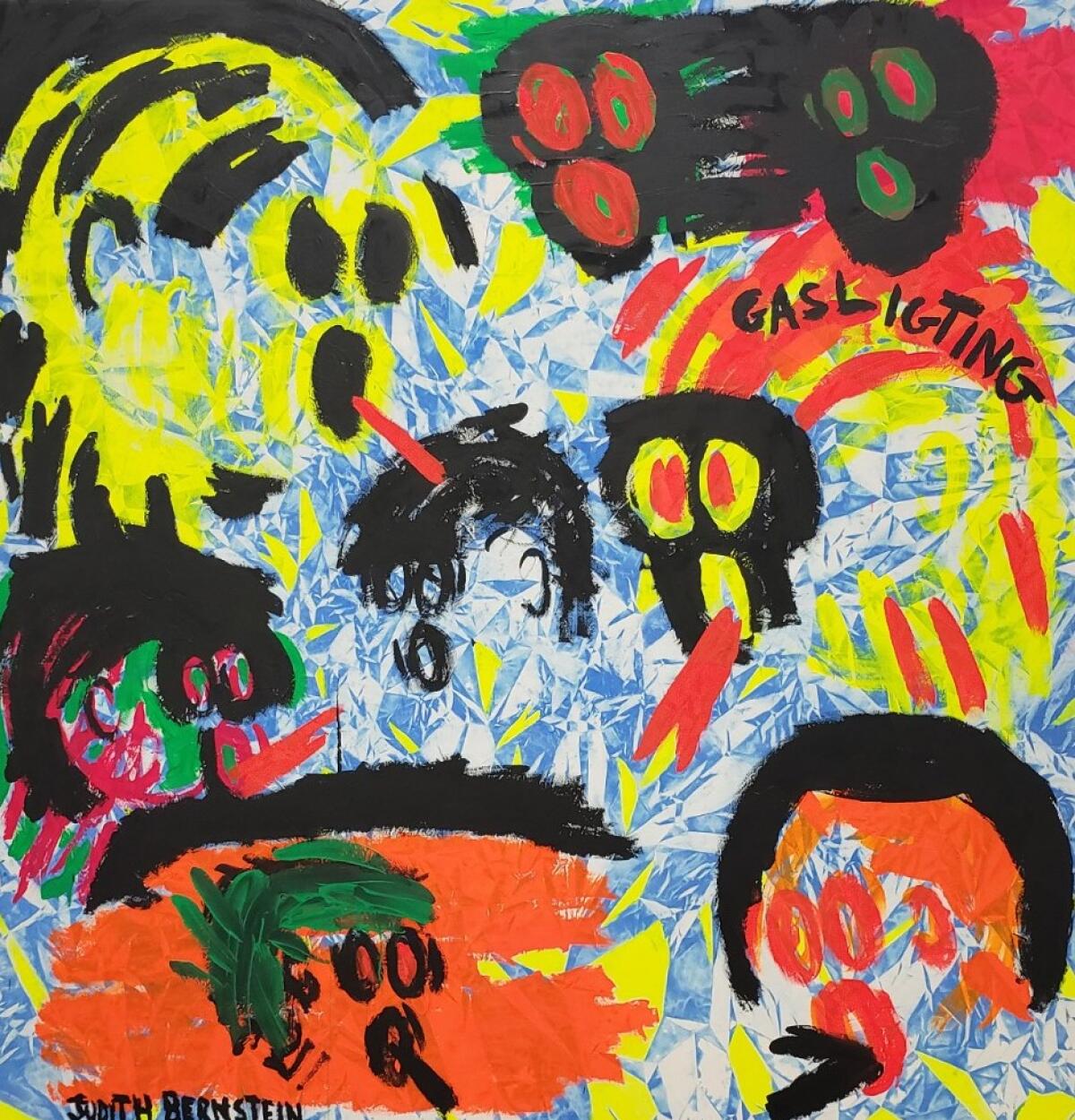

Judith Bernstein’s paintings are yelling again.

Through a theatrical constellation of bursting color, speeding brushwork, dense composition and clashing art-historical insights, the New York-based artist is producing loud, aggressively playful canvases that grab you by the lapels, determined to advance serious purposes. At the Box gallery downtown, six large and eight smaller recent paintings, selected for the occasion by artist Paul McCarthy, extend a series that Bernstein began during the dark days of the Trump administration — unsurprising for an incisive feminist artist, now 80, working during a cruel period of explosive misogyny.

Denmark was in full chaotic collapse in the early 19th century. Why was its art so beautifully serene?

She first gained notice in the early 1970s with monumental drawings that fuse a giant phallus with an enormous round head screw, the gestural energy of brilliantly handled, shaggy charcoal exclaiming furious dissent against Industrial Age patriarchy in no uncertain terms. The blood-red hue of a small, 1974 silkscreen version in vermilion, installed with four drawings in a side gallery, evokes engorgement and violence.

Genitalia are all over the recent paintings, whether flaccid penises drooping over scrotums or volatile vulvae. The latter are Expressionist descendants of Gustave Courbet’s famous, anatomically descriptive “The Origin of the World” (1866), a fragment of a larger painting of a reclining female nude that was apparently cut down by the father of French Realism — or someone else — to focus squarely on her spread legs. Bernstein renders them with vigorous brushwork, the male and female forms more familiar from bathroom graffiti than an art museum.

The word “gasligting” is slathered across several of them, its misspelling intentional. You wonder for a moment, “Is that a flub?” Or is it deliberate and therefore meaningful?

The letters are jammed in among gaping eyes and open mouths of sometimes skull-like heads. Other paintings insert the word “Trumpenschlong” amid the pictorial chaos, decorating the invented but pertinent vulgarity with vivid swastikas. (Bernstein is not subtle.) Others stipulate “We Don’t Owe U a Tomorrow,” insisting that taking control of the present matters most.

Gaslighting is calculated emotional abuse designed to make a person think they are losing their sanity. Bernstein’s simple, clever insertion of linguistic doubt resonates amid the visual noise produced by her fluorescent palette of shrieking red, screaming yellow and bombastic blue. (“Snap out of it,” the paintings virtually yell, like Cher smacking a moonstruck Nicolas Cage.) The color is made even more vivid when set against flat fields of inky blackness, crumpled azure grounds suggestive of 1960s protest era tie-dye or, in one room, heightened by black-light illumination.

The term, of course, derives from “Gaslight,” the 1944 film noir that earned Ingrid Bergman an Oscar for her role as a woman driven mad by her husband, a covert criminal. “Gaslit Nation,” a sharp political podcast hosted by Sarah Kendzior and Andrea Chalupa — scholars on the functioning of authoritarian states, who assert that Trump represented a criminal syndicate posing as a government — made the personal political.

Gaslighting is now part of the conversational lexicon about life today, with women often its immediate receptors.

Bernstein’s paintings give a feminist twist to French art brut — raw art — the work of the mentally ill, children, convicts and primitive artists, which kicked Modernist conventions to the curb in the aftermath of gruesome World War II. With the specter of fascism all around us again, the bellowing confrontation in Bernstein’s work, a combination of wit and outrage, is nothing if not timely.

Judith Bernstein: We Don't Owe U a Tomorrow

Where: The Box, 805 Traction Ave, Los Angeles, CA 90013

When: Through Aug. 12. Closed Sunday-Tuesday

Info: (213) 625-1747, www.theboxla.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.