Architect Robert Mangurian dies — a key member of SCI-Arc’s founding generation

- Share via

Architect Robert Mangurian, an influential scholar and member of a generation of designers who helped establish L.A.’s iconoclastic architecture academy, the Southern California Institute of Architecture, known as SCI-Arc, died on July 5 at the Los Angeles General Medical Center from causes related to cardiac arrest; he was 82.

His death was confirmed by Mary-Ann Ray, his longtime partner in work and in life. The couple served as principals of Studio Works, a small Los Angeles-based design office. Together, they undertook a yearslong study of Villa Adriana, the 2nd-century dwelling of the Emperor Hadrian near Rome, which recorded important information about how an on-site temple employed sunlight during a solstice.

Mangurian and Ray also designed a number of educational structures, including the Rose and Alex Pilibos Armenian School in Hollywood (completed in 2000) and the West Adams Preparatory High School (2007) in Pico-Union. The latter project arranged slender classroom and administrative buildings around open-air courtyards with steps for congregating. The high school, which abuts the 10 Freeway, is in a park-poor area. “We wanted to make a space,” says Ray, “where kids didn’t want to leave.”

Chris ‘Spanto’ Printup, Born X Raised founder and treasured champion of Los Angeles culture, died Wednesday morning after succumbing to injuries sustained in a Sunday car accident. He was 42.

Craig Hodgetts, a friend and former collaborator who helped establish the precursor to Studio Works, a New York-based office called simply Works, recalls Mangurian as a curious intellectual who was as devoted to big-picture concepts as he was to the details of execution.

Among the various projects they worked on together was a Postmodern gallery and living space for art dealer Larry Gagosian in Venice in 1981. The building contained a dramatic circular courtyard with a jagged, wooden staircase that led to the second story, as well as patterned floors fabricated out of marble tile. “Robert himself insisted on helping lay the tiles, so they were precisely the way that they were envisioned to be,” remembers Hodgetts. “Robert had a religious devotion to the role of architecture.”

Mangurian, however, will likely be best remembered for his influential role as an educator — first on the architecture faculty at UCLA in the early 1980s, followed by a decadeslong presence at SCI-Arc, where he served as director of the graduate program from 1987 to 1997. In a 2001 dispatch, former Times architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff describes a professor interested in expanding the boundaries of the field, teaching courses on subjects such as the relationship between architecture and film or architecture and fashion. “They became wildly popular with students,” Ouroussoff wrote, “because they seemed to expand on conventional notions of what architects do.”

Books for the housing future: Henry Grabar on how parking has wrecked cities and Frances Anderton on the residential designs that can help bring them back.

In his architectural newsletter, “The Horizontal Fault,” Peter Martinez Zellner, who taught at SCI-Arc alongside Mangurian and Ray beginning in the late 1990s, describes architectural reviews with “a festive quality” — “suggesting that architectural education is more than just checking off the boxes on a syllabus or mastering software.”

Current SCI-Arc director Hernán Díaz Alonso hailed Mangurian as “a giant, both as an architect and in the formation of SCI-Arc.”

Robert Emerson Mangurian was born in Baltimore on April 15, 1941, the youngest son of George and Margaret Mangurian. Within a decade, the family had relocated to the L.A. area — Glendale — after Robert’s father, an aerospace engineer, took a job at Northrop Corp. As Mangurian once joked with a reporter from an Armenian weekly: “I was the first Armenian to live in Glendale.”

In designs for two schools, a pair of instructors puts lessons into practice.

But the bulk of his youth was spent in Rancho Palos Verdes, where the family settled to be closer to Northrop’s headquarters in Hawthorne.

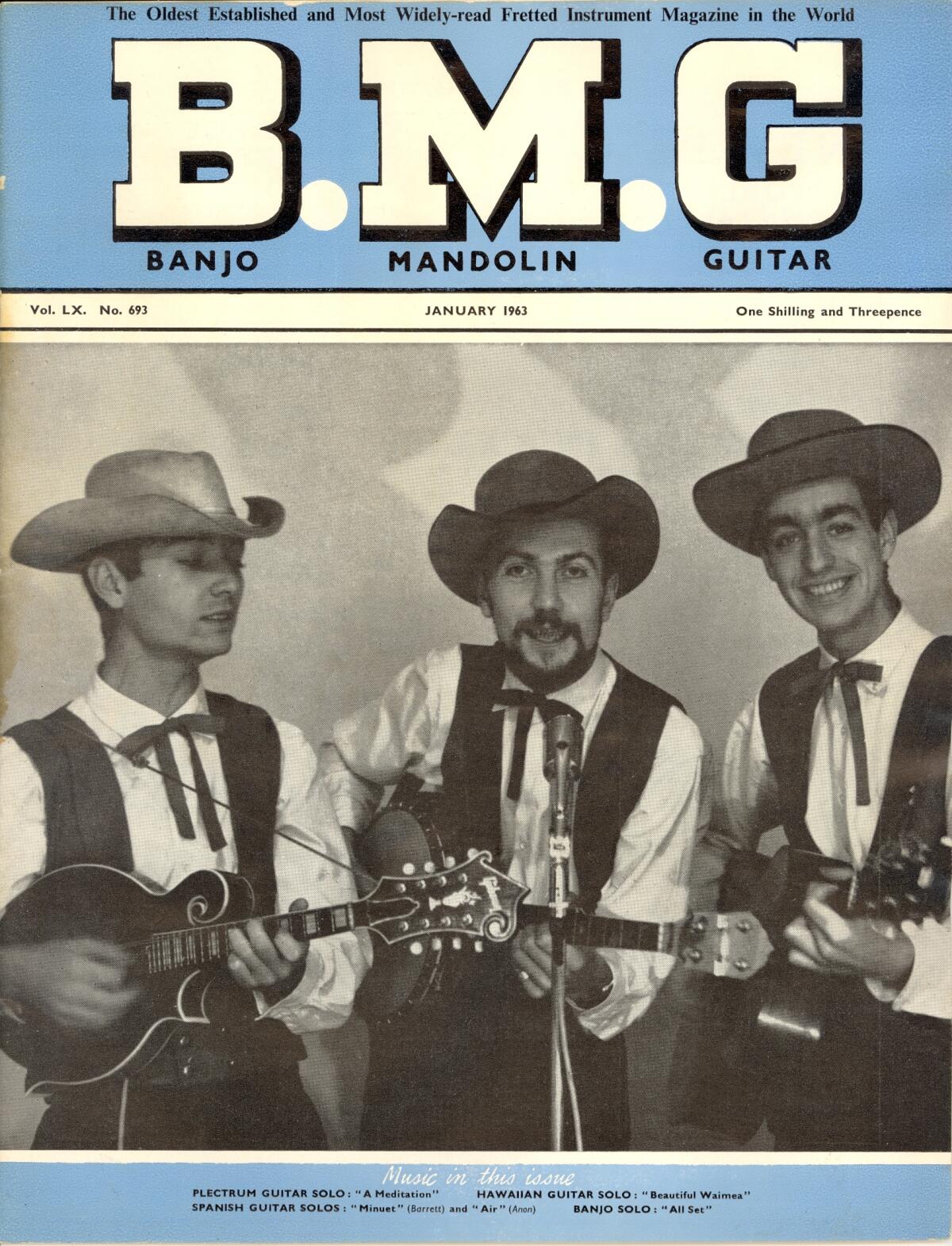

Mangurian’s undergraduate studies took him to Stanford University, but ever restless, he decided, with his brother David, to take time off from school to tool around Europe in a Citroen they acquired for $800. As a mandolin player in a band called the Tennessee Three, he spent several months in England gigging in pubs that had once hosted folk stars like Bob Dylan.

On his return to the United States, Mangurian transferred to UC Berkeley, where he majored in architecture — motivated, he once said, more by an interest in history than in the formal particulars of the field. “I fell into it,” he once said. “I like the history part better.”

After college, a succession of jobs followed. He moved to New York City to work at Conklin & Rossant, the firm that helped plan the city of Reston, Va., and while there he connected with Hodgetts, a Yale University graduate who had established Works with fellow architect Lester Walker and graphic designer Keith Godard. One of their first projects was a neon-illuminated retail storefront for toy manufacturer Creative Playthings — a well-received project that Mangurian helped see to fruition.

Works’ office was located on Union Square, in an office right above Andy Warhol’s Factory studio. Ray says the group would prank Warhol by dangling a blaring radio on a rope outside the artist’s window.

Hodgetts and Mangurian teamed up again in the late 1970s as Studio Works to produce a mixed-use building for a social services agency in Columbus, Ohio.

The architects took the mission to heart, embedding themselves with South Side Settlement staff to understand their needs. As Mangurian told The Times’ John Dreyfuss in 1979, “We got our information from being in the client’s operation.”

Review: ‘Confederacy of Heretics’ a delicate task

The project suffered stops and starts, including a year when Mangurian went off to Italy after winning the Rome Prize in 1976. But the building was ultimately finished in 1980 — complete with an outdoor performance space with a swooping stairway designed by artist Alice Aycock. (Unfortunately, it has since been demolished.)

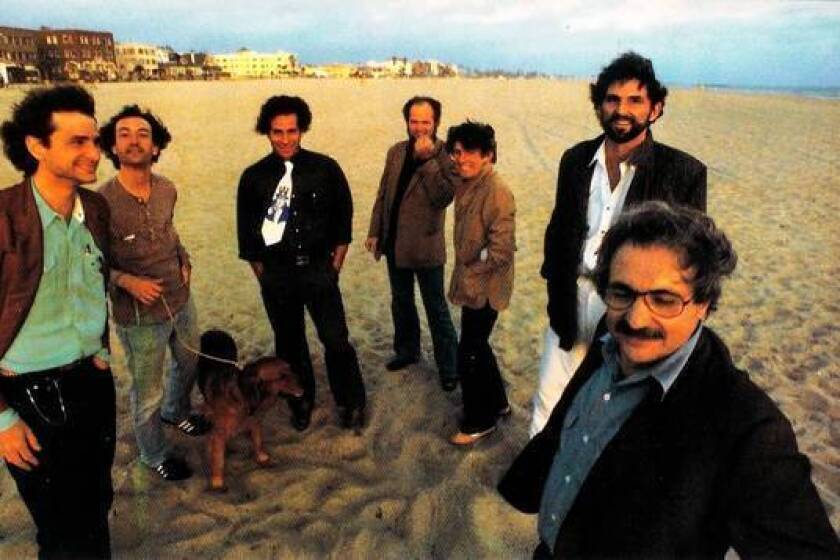

Afterward, the architect returned to Los Angeles to teach at UCLA — and quickly immersed himself in the city’s experimental design scene, where figures such as Thom Mayne, Frank Gehry and Eric Owen Moss were rebelling against the glassy facades of late Modern architecture and offering a more rugged interpretation of Postmodernism than what was emerging from the East Coast. Mangurian, fresh from his travels in Italy, likewise helped bring a fresh vocabulary to the form.

During this time, he once again teamed up with Hodgetts (already living in L.A.) to participate in a now legendary DIY exhibition series titled “Current L.A.: 10 Viewpoints,” which was staged in Mayne’s Venice home. Dreyfuss reviewed the shows at length in The Times, giving the shows — and the architects within them — remarkable prominence.

The partnership of Mangurian and Hodgetts ultimately petered out. Hodgetts got into Hollywood, working on production design, and he later went on to establish the architectural studio Hodgetts + Fung with Hsingming Fung. And Mangurian turned his attention to research and teaching. The two, however, remained lasting friends. “I would always invite Robert to my juries at UCLA and he would invite me to SCI-Arc juries,” says Hodgetts, “and we would continue to meet at this little Mexican restaurant on Rose Avenue.”

SFMOMA acquires a prized capsule from metabolist architect Kisho Kurokawa’s legendary building. Plus

Over the course of his career, Mangurian also collaborated with artists such as Eric Orr, Vito Acconci and Ai Weiwei. In 1985, he and Ray got to know each other when the two began working together on the model for artist James Turrell’s Roden Crater project, a decadeslong effort to turn an extinct Arizona volcano into an observatory. “Turrell,” says Ray, “claims to be our matchmaker.”

Since then, the couple — later joined by co-principal William Anthony Hogan III — collaborated on numerous projects. They established an experimental design lab in China and worked on designs, including their unorthodox plan for the Armenian School in Hollywood: an ark-like structure set on pilotis that Ouroussoff described as containing “a sweet, offbeat quality that is genuinely disarming.”

Music was formative to Mangurian as a young man, and it was present in his final hours.

As the architect lay in his hospital bed, Ray put the Stanley Brothers’ ”Angel Band,” a mournful tune that features a prominent mandolin, on the sound system. “It’s about ascending into heaven,” says Ray. “It was perfect.”

In addition to Ray, Mangurian is survived by his older brother David, as well as his son Tony from an earlier marriage to Paula Stephens. Stephens died in 2005.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.