A wrongful conviction leads to deeply personal art about the ‘broken criminal justice system’

- Share via

The life-altering phone call came unexpectedly. It was August 2012. A Thursday, around 4 p.m.

Sherrill Roland was packing to leave for grad school, where he’d be pursuing an MFA in studio art at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

It was especially warm in his childhood bedroom in Asheville, N.C., and Roland had the whole day to languidly pack. His hard-shell suitcase lay open on the bed. He tossed in T-shirts, jeans, sweatshirts, then tucked a sketchbook and laptop computer into his backpack.

A cellphone ring pierced the silence. Roland didn’t recognize the Washington, D.C., number, but he’d spent time in the area since getting his bachelor’s degree in design in 2009 from the Greensboro school, and he’d taught computer coding to teens at a tech camp in Baltimore. So he knew people in the area. He figured the call was from a friend with a new phone number.

The gravely serious voice on the other end of the line, that of a detective, got right to the point. There was a warrant out for Roland’s arrest. The detective would not say what the charge was, but the alleged crime had taken place in Washington, the officer said, and Roland needed to travel there and turn himself in immediately so he could appear in court. The start of grad school would have to be put on hold.

So too would Roland’s life as he knew it for the next several years. He finished the first year of grad school while awaiting trial in D.C., shouldering the burden of what lay ahead. (He declined to say what he was accused of for privacy reasons.) After the felony charges were reduced to misdemeanors, Roland was given a bench trial, appearing before a judge without a jury, and he was convicted of a crime he said he did not commit. Roland was sentenced to one year and 30 days, of which he served more than 10 months in a 7- by 9-foot cell at the D.C. Central Detention Facility before being exonerated in 2015.

That harrowing experience — the angst-ridden year waiting for his trial, the time spent behind bars and the painful process of acclimating to the second year of grad school afterward, in a world he felt was devoid of trust — provides the basis for the art Roland has produced since.

“A lot of my work, it’s really trying to amplify my experience,” he says. “I assumed I had agency out in this world as a free man that I later realized I didn’t.”

His solo exhibition “Sherrill Roland: do without, do within” opened last week at L.A.’s Tanya Bonakdar Gallery. It’s his second solo show with the gallery — the first was at its New York location last year — and his first art exhibition in Los Angeles. “Do without, do within” features wall sculptures, installations and prints addressing Roland’s personal journey as well as what he refers to, during a walk-through of the exhibition, as a “broken American criminal justice system.”

“I do wish the system as it is could be abolished,” he says. “I’m just trying to place perspective from where I sit and ask why or ponder a deeper resonance of my experience.”

Roland creates art only out of materials he had access to, or saw, while incarcerated. One series in the exhibition, etched acrylic wall sculptures called “Thirsties,” uses Kool-Aid as a primary material; it’s something Roland drank frequently while behind bars. The works look like seemingly happy, candy-colored abstracts employing a smattering of dots between sheets of clear acrylic coated with resin. They could be landscapes of vaguely shaped fruit trees — “fields of dots,” as Roland describes them — in a spectrum of mostly red, orange, yellow and green.

Roland says that he’s colorblind and that the works also take inspiration from a pattern seen in the Ishihara red-green color deficiency vision test. As such, the works speak to vision, identity and trauma.

“Me being seen is almost as rare as me meeting someone who knows what it’s like to be red-green colorblind and an exoneree,” Roland says.

The works are also nods to the character of the Kool-Aid Man, which led to a Marvel comic, along with the story’s evil band of dehydrating Thirsties. Some of the works feature inverted smiles, others elongated, tongue-like swirls.

“I just was taken by all the people who were thirsty in the comic book — without being quenched — mouth open, sweat pouring, very tired, very depleted. I abstracted that,” Roland says. “I’m interested in this idea of seeing desperation, not only within somebody else but also recognizing it within yourself.”

In jail, Roland passed his time writing letters, staring up at a dirty cell window. A series of wall sculptures, “Boneyard,” are vertical diptychs based on brutalist architecture and windows from city jails. They’re made of concrete, cut steel and cotton, the latter referencing “bed sheets, state-issued T-shirts, white socks, white boxers, two of everything,” Roland says. Each frame features rectangular shapes that resemble elongated window panes, with different numerical configurations inside each one. The works resemble domino tiles, a game Roland played while in jail.

“The game is a way of counting numbers and counting time,” Roland says. “And windows [are] a way of counting bodies outside.”

A group of embossed prints incorporates text from a late ’90s Associated Press article from a newspaper in Roland’s hometown about inmate firefighters in California. The prints also use red Kool-Aid as a pigment, giving the paper a smoky, burnt-looking undertone, like a smoldering fire.

“It’s taking this language and trying to consider being in that position, seeking freedom through fighting fire,” Roland says. “What would it take for me to fight fire for my freedom? You put your life on the line.”

The large-scale installation “Conflict Resolution” is particularly effective. The work brings to life an unpleasant memory from Roland’s time in jail. After the HVAC system broke in his housing unit during the muggy heat of a D.C. summer, the guards provided tall standing fans, which blew air through slots in the cell doors. With far fewer fans than cells, inmates were soon fighting over them.

“At night, they locked us in, and right before, some guys would hop out and turn these fans to their door before it shut,” Roland says. “Fighting over the things, they ended up breaking. And the pieces turned into weapons because they had springs, they had screws. Whole swords. Again, it’s about desperation, being without — what does that look like?”

The art piece consists of nearly 5-foot-tall standing fans, swirling at a painstakingly slow pace. Roland serrated the edges of the fan blades, so they look like knives, their shiny chrome edges glinting in the gallery light. He cut slots into the fan head guards. It’s simple but triggers immense frustration.

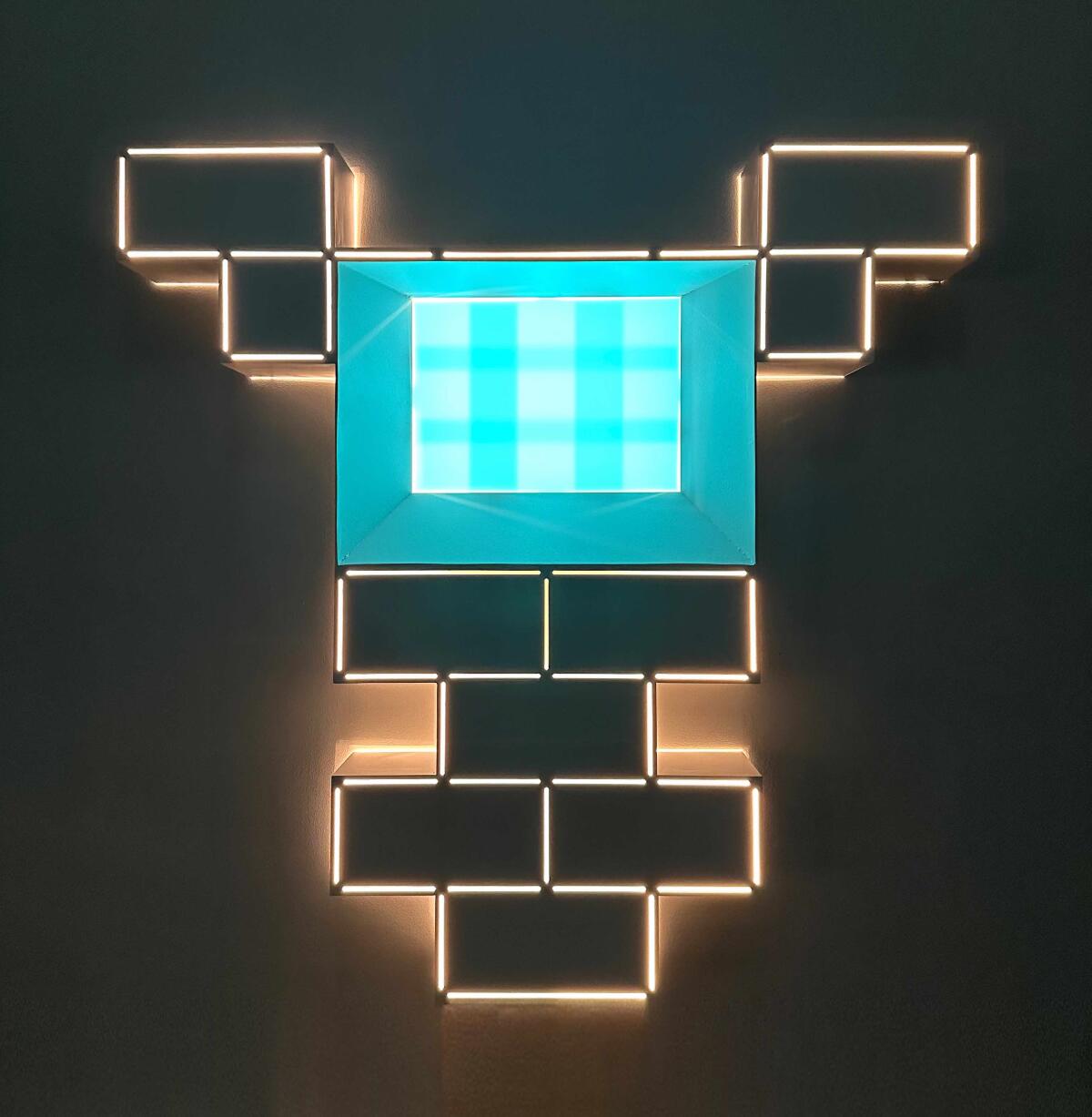

Roland’s two light boxes in the exhibition are both hauntingly beautiful and tragically sad. The works, “Forecast,” resemble cross-shaped cell windows on cinder blocks. The window panes glow either blue or yellowish pink and feature crisscrossing shadows that look like thick steel bars.

Roland says his cell window, which was tinted and positioned high up on the wall, was so dirty and weathered that he couldn’t make out actual objects through it. “I couldn’t see a bird, I couldn’t see a cloud,” he says. He’d lie back and stare up at the window, looking at a block of blue haze in the daytime, if the weather was clear, and yellowish-green in the nighttime, from the security lamps outside.

“How depressing is this window,” Roland says. “I love looking out of [air]plane windows, this metaphor of searching for hope. If I could look up at the sky and actually daydream from this window, it’d be great, but it wasn’t. It was so confined, it was like a fake window.”

The light boxes also memorialize the last time Roland remembers looking out of a window for hope. He was 4 and his father had just been shot. He gazed out of his bedroom window that night.

“I saw houses on the hills. I could see his mother’s — my granny’s — house,” Roland says. “Next to their house was the top of the hospital that he passed away in. And on top of that was a glowing cross.”

In 2017, after he’d been exonerated and finished graduate school, Roland staged a two-day performance at Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions in which he sat outside the gallery in a 7- by 9-foot space marked with duct tape and told his story to passersby who agreed to step into his box. It was a way of both shining a spotlight on the incarceration experience as well as processing and amplifying his personal narrative.

He hopes “do without, do within” will do the same.

“I feel a duty, the burden of surviving,” he says. “It’s my responsibility to share this experience that you shouldn’t have access to but that you do need to know.”

Art Exhibit

‘Sherrill Roland: do without, do within’

Where: Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, 1010 N. Highland Ave.

When: 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday. Through June 24

Info: (323) 380-7172 or www.tanyabonakdargallery.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.