Editorial: Release California from the prison of over-incarceration

- Share via

As COVID-19 infections reached pandemic status in 2020, more than one of every 100 working-age American adults were locked up in jail or prison. Because they could take few steps to protect themselves from disease while in cells or closely packed bunks, they became infected at especially high rates. And because most of them eventually went home or came into direct contact with their family members and correctional officers who brought the infection home, jails and prisons became hazardous to the public at large.

But incarceration was already a serious public health hazard long before the pandemic. The absence of so many parents and other adult relatives added, and continues to add, yet one more layer of trauma to communities already saddled with the least wealth, the fewest housing options, the lowest employment levels, the foulest air, the worst-performing schools, the greatest rates of homelessness and the most untreated serious mental illness and substance use disorders. These are among a set of factors that social scientists call social determinants of health, and they predict educational attainment, earning ability and even lifespan.

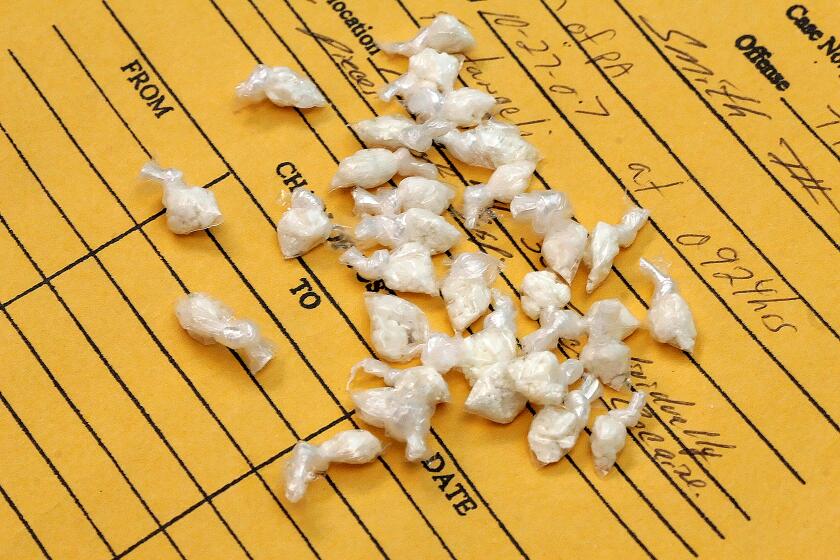

America responded to the 1980s crack epidemic with police and prisons instead of public health. Now look where we are.

Crimes rate, too, are a social determinant of health, and incarceration — meant to drive those numbers down — must no doubt play part of the solution in some cases. But it’s also part of the problem and is itself a social determinant of health, contributing to an endless cycle of untreated illness, social dysfunction, behavioral problems, crime, incarceration, recidivism and parental absence for another doomed generation.

There are many cases in which the more effective, longer-lasting response to individual criminal behavior is a regimen of treatment, housing assistance and other aid, rather than jail or prison time. Failure to deal with health issues caused by crime and incarceration makes communities much less resilient when hit by epidemics such as crack in the Black community in the 1980s and ’90s and COVID-19 currently.

Los Angeles County officials have known that for years, but it was not until March 2020, just before the COVID-19 lockdown, that the Board of Supervisors adopted its Care First, Jail Last program, also known as Alternatives to Incarceration. The pandemic had a mixed effect. It underscored the immediate need to reduce the jail population and it brought the region billions of dollars in federal emergency assistance, but it also slowed implementation of the program, which has yet to launch.

We need L.A. County’s Care First, Jails Last Alternatives to Incarceration program moving forward, fully funded.

California officials, too, have been well aware of the need to find alternatives to incarceration, and have put into place programs to incentivize prison residents to participate in health and rehabilitation programs.

But the state should also follow L.A. County’s lead by studying a more complete program of alternatives to incarceration, including diversion from the criminal justice system for people accused of nonviolent crimes who are dealing with mental illness. Assembly Bill 1670 by Assembly Members Isaac Bryan (D-Los Angeles) and Chad Mayes (I-Rancho Mirage) would create a commission to consider options.

Police and prosecutorial organizations oppose the proposal for the same reason they oppose most criminal justice reforms: It falls outside the scope of their arrest-and-jail approach. But that’s part of the dismal cycle that drives so many poor health outcomes in so many communities. California needs to free itself from that self-destructive approach.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.