Lizzo tweeted ‘cancel culture is appropriation.’ Not everyone agreed with her point

- Share via

Is it possible to cancel cancel culture?

Lizzo is trying to — at least the kind of cancel culture that she considers “trendy, misused and misdirected.”

“This may be a random time to say this but it’s on my heart.. cancel culture is appropriation,” the Grammy-winning singer tweeted over the weekend.

“There was real outrage from truly marginalized people and now it’s become trendy, misused and misdirected,” she continued. “I hope we can phase out of this & focus our outrage on the real problems.”

With her dance competition series “Lizzo’s Watch Out for the Big Grrrls,” and a new project she can’t yet discuss, the singer is embracing her journey -- and herself.

But the “2 Be Loved” and “About Damn Time” singer-songwriter did not give any examples of how cancel culture has been appropriated or “misused.” And the open-ended claim lit social media aflame, prompting people to fill in the gaps.

Her supporters applauded the message, with many online calling for more accountability for wrongdoing, rather than using the word “canceled” to avoid actual consequences.

“Cancel culture should be used to make people take accountability for their actions and educate themselves on the communities and groups they may have hurt with their actions,” one user replied.

Another person said they “don’t want people to be canceled.” They added, “I want people to be *held accountable* and to receive consequences according to the bad action/crime that they did. Is this too much to ask?”

For her People’s Choice Awards speech, Lizzo invited 17 activists she believes ‘deserve the spotlight’ more than she does. And Stevie Nicks approves.

YouTuber Jessica Ballinger agreed with Lizzo, writing, “There are very real issues that warrant outrage… I sometimes wonder if cancel culture stems from people feeling impotent against those bigger issues, so they go after simpler targets to feel better about themselves, like they did something.”

However, others disagreed. One user said Lizzo’s tweet was “not a good take,” while another said they were “sick of hearing celebrities whine about cancel culture.”

Another took direct issue with Lizzo labeling cancel culture as “appropriation” and claimed that “mob rage disguised as consequence doesn’t (and never did) belong to any particular group of people.”

But the opposite may be true. As one user pointed out, mentioning its use on “Black Twitter,” the term “canceled,” just like “woke,” actually does trace its origins to Black culture.

Comedy historian Kliph Nesteroff and comics Donnell Rawlings and Tiffany Haddish explain the origins of modern-day cancel culture and its historical equivalents.

Washington Post reporter Clyde McGrady, who writes about race and identity, looked into the history of canceling in 2021, after white conservative politicians used the term to complain about companies’ decisions to be more inclusive.

“Young Black people have used these words for years as sincere calls to consciousness and action, and sometimes as a way to get some jokes off,” McGrady wrote. “That White people would lift those terms for their own purposes was predictable, if not inevitable.”

McGrady found that the use of the word “canceled” to express cutting someone off for their unacceptable behavior may have begun with singer-songwriter Nile Rodgers and the 1981 single “Your Love Is Cancelled” by his band Chic.

It is the view of these 151 signers that cancel culture, stemming from the angry young internet wokes who demand to dominate the direction of the public discourse, is new. That is false.

Its use on Black Twitter was not to “activate a boycott or run anyone from the public square,” McGrady wrote, but was “more of a personal decision, a way to say we don’t really kick it anymore: You stepped out of line, and now I’m done with you.” He then gave the example of Black fans expressing contempt for Justin Timberlake after he dissed Prince.

“The power of cancellation lay with the canceler: How much social capital were they divesting, and how many others would follow suit?,” he continued.

The article went on to trace the ways cancel culture evolved into a more robust “call-out” culture, or calling for more social and systemic change, which hit a fever pitch amid the #MeToo movement and again in 2020 after the murder of George Floyd. Like Lizzo’s supporters, McGrady worried the word is now being used as “a catchall defense for those trying to evade public criticism of any kind.”

“Cancel culture” has been with us since this country began — did anyone actually see “Hamilton”? So why is a group of esteemed writers wringing hands about the way a new generation uses it?

This is not the first time Lizzo has called the term into question.

In 2018, Ye — then known as Kanye West — ranted to TMZ that slavery was a “choice.” Many online started calling on people to stop listening to Ye’s music, prompting die-hard hip-hop heads to remove his tracks from their playlists. Lizzo responded with a Twitter thread questioning whether any of the cancellations would work.

“We ‘cancel’ or boycott artists but how effective has that been for us?” she wrote in the thread, admitting that she doesn’t buy music anyway. “I’m gonna use outrage and respond with progress.”

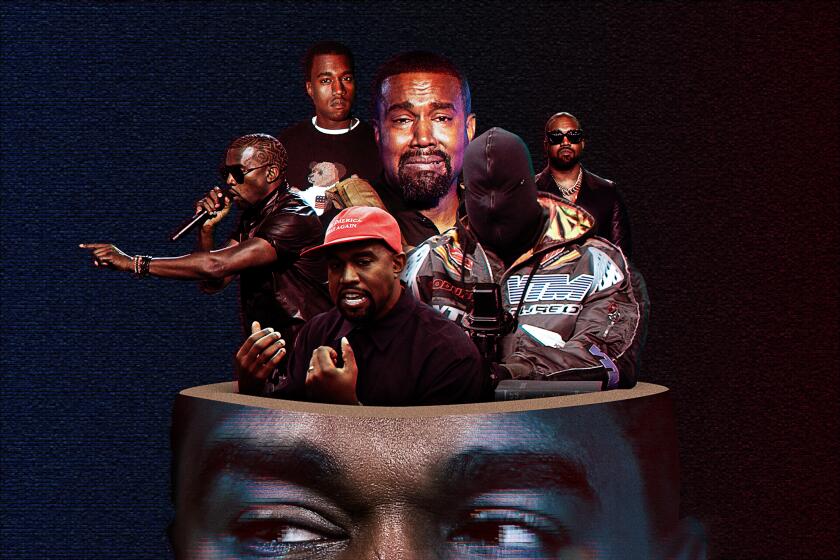

West hit a new low Thursday by appearing on Alex Jones’ show with white supremacist Nick Fuentes. What’s behind his spiral from hip-hop hero to far-right troll?

She went on to blast Ye for his assertions on slavery, writing that it was her job “to create a new legacy” of activism, invoking the names of Sojourner Truth and Ella Fitzgerald. She called on others, including Ye, to build their own legacy.

“My legacy is my FAT FEMME FREEDOM,” she wrote. “I show it on my body and in my music. Ella Fitzgerald was banned from music clubs for being a black woman, I appreciate her fight every night when I’m on tour. My legacy exists because that should never happen again.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.