Virginia Dwan, influential L.A. gallerist and risk-taking arts patron, dies

- Share via

For years to come, L.A. artists groused and laughed about the night French artist Yves Klein debuted his film “Monotone Symphony” at the Dwan Gallery in Westwood. It was June 1961, and Klein, in the midst of his first West Coast solo show at the gallery, was excited to share this new work. It documented a performance he’d recently done in Paris, in which nude female performers rolled themselves across a giant piece of paper covered in blue paint and laid out on the floor. As the women painted and rolled, members of a small orchestra played single notes for extended periods of time. The experience was too much for some. Artist John Altoon walked out.

“It caused a furor,” Virginia Dwan recalled in a 1984 oral history. Dwan, who had opened her eponymous gallery two years before, had gotten used to this behavior from local artists, who were possessive of their small art scene.

“In Los Angeles, I felt that I had to defend just about everything I showed to everyone.” But it was worth it. She loved Klein’s art, and wanted it to be seen. The works “really pulled me in and absorbed me in their intensity,” she said in the oral history.

“I think that was what was so remarkable about her,” recalled Rosamund Felsen, who attended Dwan Gallery’s exhibitions in the early 1960s and went on to open her own celebrated L.A. gallery in 1978. “It wasn’t about her at all. It was about what could be accomplished that had never really been accomplished before, because she knew that these artists had new ideas.”

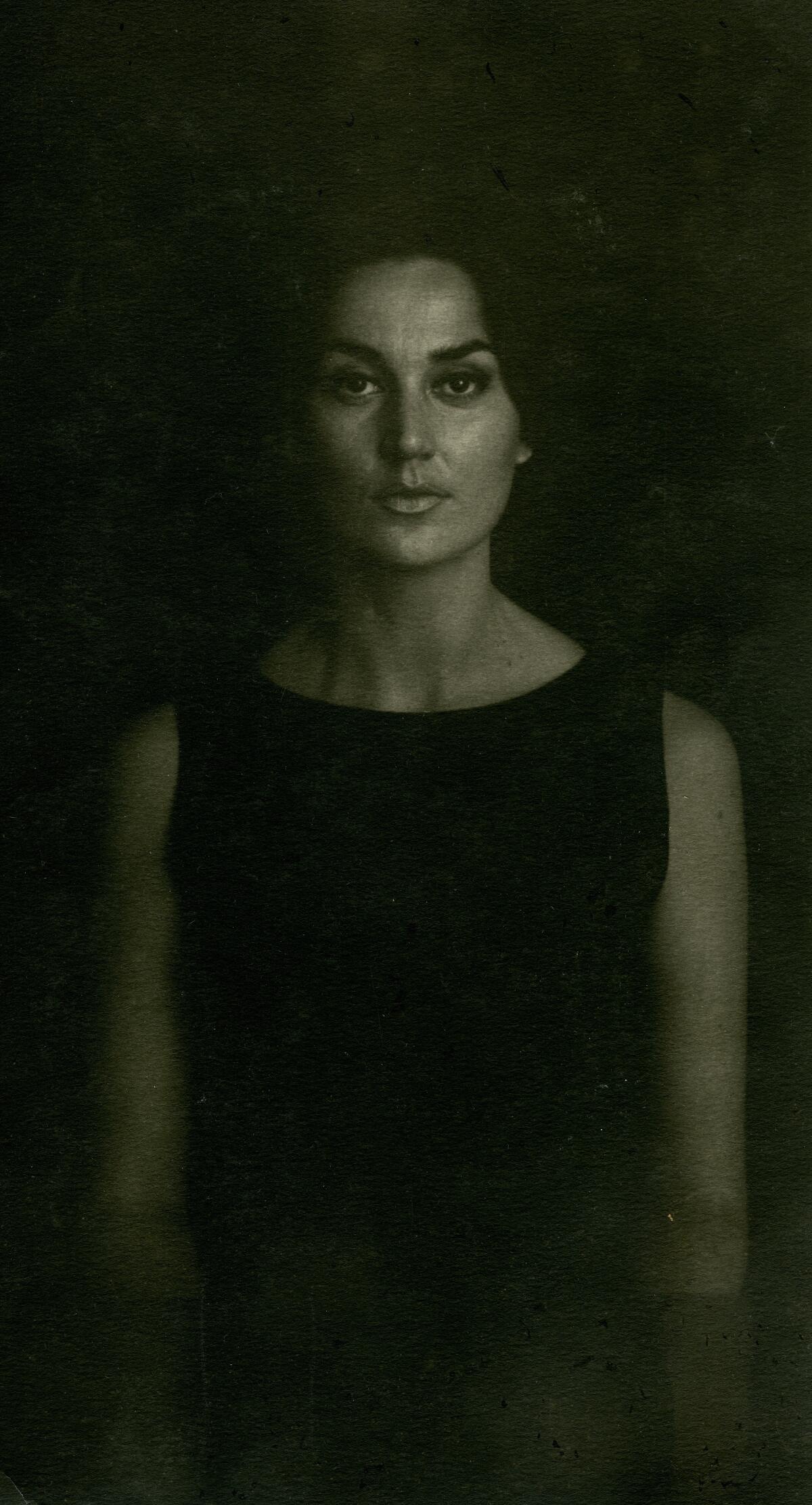

Virginia Dwan, whose gallery in Los Angeles and then New York supported some of the most experimental artists of the 20th century, died Sept. 5 from pancreatic cancer at 90.

Born in Minneapolis in 1931, Dwan had her first formative experience with art as a teenager. At the prodding of her mother, she went to the Walker Art Center to see engravings by Wanda Gág, a comical children’s book illustrator. She got pulled into the early American Modernism of John Marin and Joseph Stella instead. The experience left her speechless and “full of fascination,” she later recalled. After high school, she and her mother moved to Los Angeles so Dwan could attend UCLA. At first, she studied art, but the department at that time was averse to modern art, so she felt out of place. She changed her major to psychology.

In 1950, she married psychology graduate student Peter Fischer, and one month after her 19th birthday, she gave birth to her daughter, Candace. When she turned 21, a family lawyer traveled to Los Angeles to explain the terms of her inheritance. Her father, who had died in 1944 from heart failure after a bout of pneumonia, was the son of John Dwan, a co-founder of the Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Co., which became the multinational conglomerate 3M. Her inheritance made her wealthy.

She divorced in 1953, took a leave of absence from school, left Candace with her mother, and traveled to Europe and New York to see art. When she returned, she began frequenting Frank Perls Gallery in Beverly Hills, talking art and drinking coffee. When she told him that she wanted to start her own gallery, he asked, “How much money do you want to lose?”

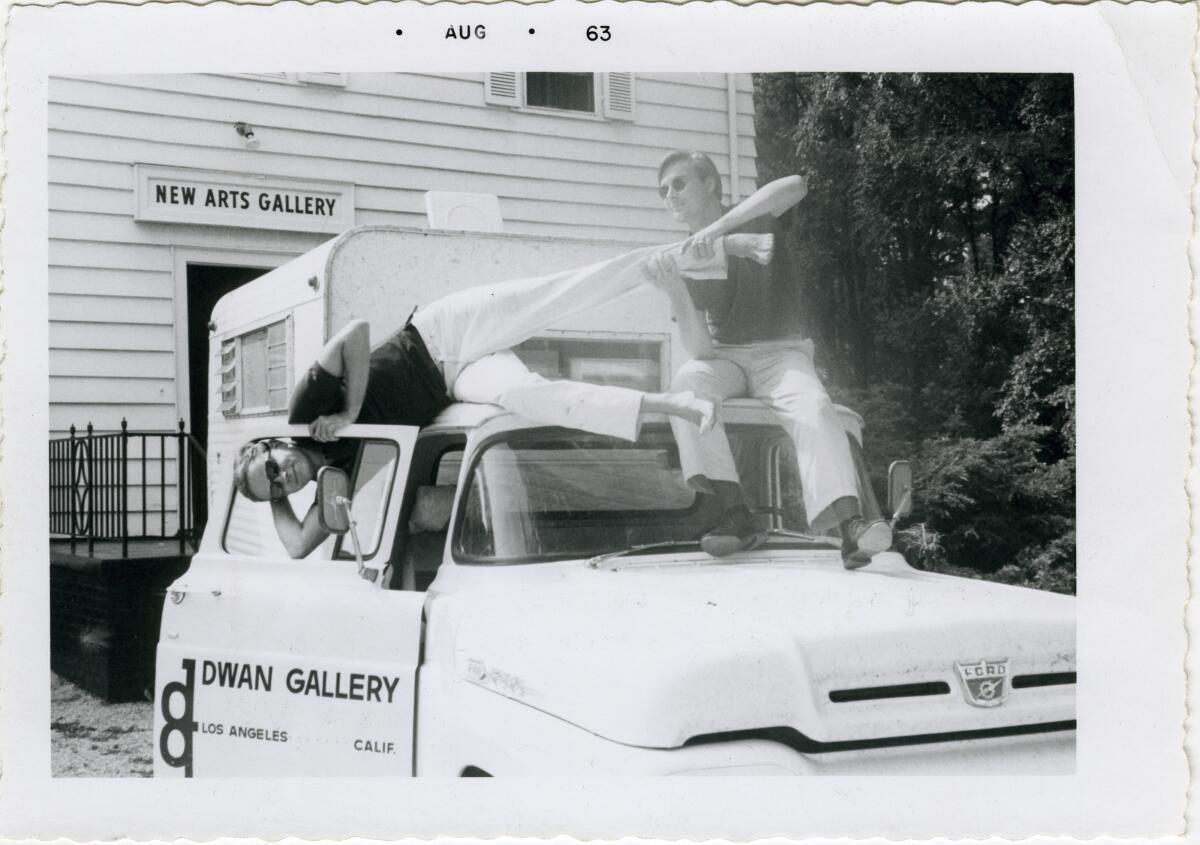

The comment put her off the idea until she married UCLA medical student Philippe Vadim Kondratief in 1958. Kondratief, whose mother ran a gallery in Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y., encouraged her interest in art. In 1959, she opened the Dwan Gallery out of a Westwood storefront.

By the time her gallery opened, Walter Hopps and artist Ed Kienholz had started Ferus Gallery, the only other gallery in the city dedicated exclusively to new art by young artists. Ferus opened on La Cienega Boulevard, joining other galleries in the area and beginning a modest art scene. Dwan had opened in Westwood on purpose — Kondratief was in school there, and it was adjacent to wealthy Bel-Air and Beverly Hills — but it still left her on the outside, all the more so because Ferus’ proprietors saw her as competition. “I felt very threatened by her situation at the time,” said dealer Irving Blum, who joined Ferus in 1958, in a 1977 oral history.

“We write often, all of us, about the importance of Walter Hopps and the Ferus Gallery,” said Richard Koshalek, the president of Art Center and former director of the Museum of Contemporary Art. “But we always forget to mention Virginia Dwan.”

In its early years, Dwan Gallery showed some local artists, most notably Kienholz (who left Ferus’ roster in 1962), but, more significantly, it brought New York and European artists to Los Angeles, introducing them to the city and its artists. Dwan, who said she had no clear idea what she was doing when the gallery opened, started traveling to New York to visit artists’ studios. She read art magazines voraciously. She began visiting Paris as well, where she met artists associated with the newly formed Nouveau Réalisme movement, a reaction against the romanticism of abstract painting. The very day she first saw Yves Klein’s work, she arranged an L.A. show with him.

“She was already extremely adventurous and ready for everything,” her daughter said. “It was a lot of fun at moments, being her daughter, because the artists were doing pretty wild things.”

Artist Niki de Saint Phalle did one of her shoot performances — shooting bullets at canvases covered with paint-filled plastic and plaster objects — in the hills above Dwan’s Malibu Colony home. The resulting painting, explosive with color, was installed alongside Dwan’s swimming pool, next to a cannon made by Saint Phalle’s partner, artist Jean Tinguely. Many of the artists were also happy to entertain their gallerist’s young daughter: Robert Rauschenberg, who had his first West Coast show at Dwan Gallery in 1962, taught Candace how to transfer images; the wily, pop-adjacent painter Larry Rivers gave her drawing lessons and French Nouveau Réaliste Martial Raysse traded one of his paintings for one of Candace’s.

In 1964, soon after her marriage with Kondratief ended, Dwan decided to rent an apartment in New York City. “It seemed to be the moment to displace myself and see how I felt about it,” she said. She left her gallery director, John Weber, in charge of the L.A. space.

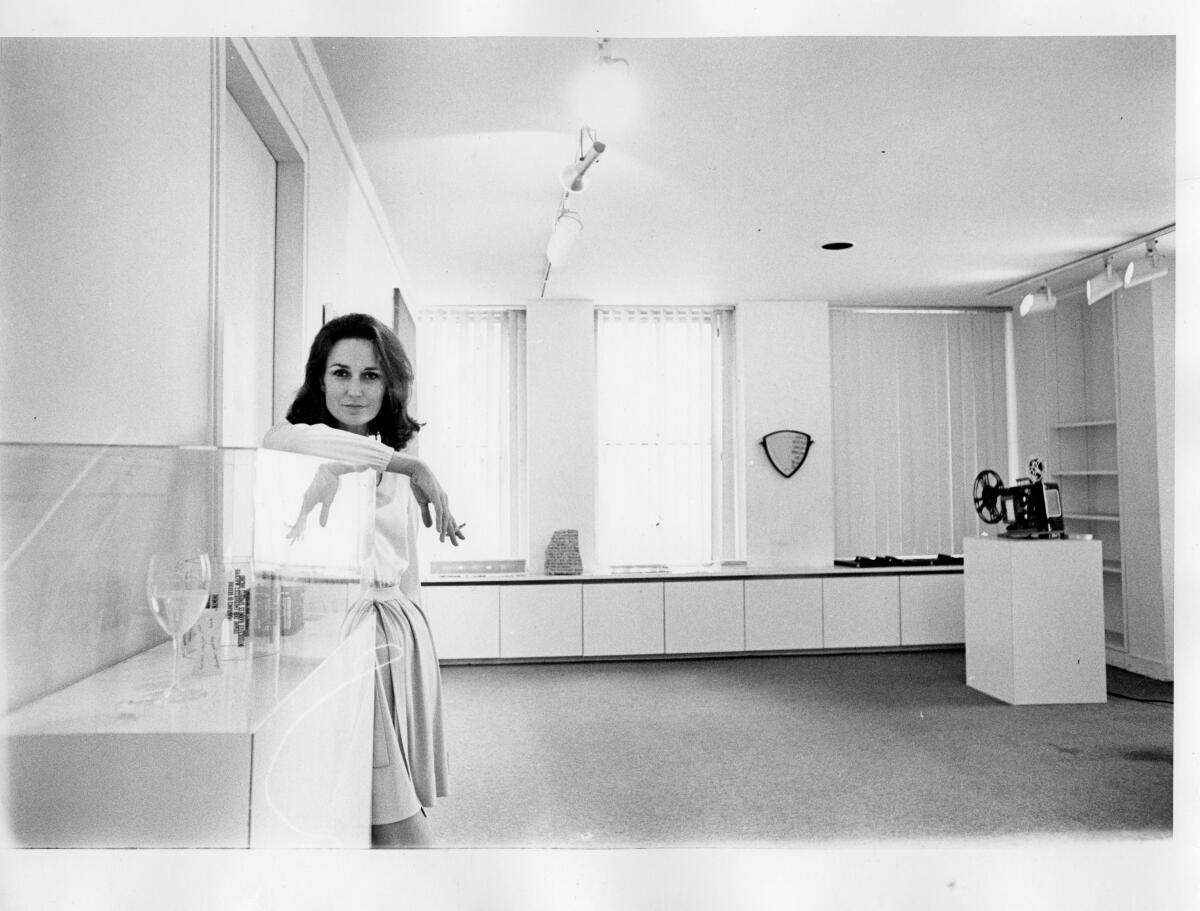

She opened an East Coast iteration of Dwan Gallery on 57th Street in 1965, making her the first dealer with spaces operating in both cities. She inaugurated her New York gallery with Kienholz’s “Barney’s Beanery,” a life-size replica of the West Hollywood watering hole. It was a bold choice: Not only was the artist barely known beyond L.A., but the installation intricately referenced a spot mostly familiar to Angelenos.

The “Beanery” was still on view the day artist William Anastasi came to see Dwan. Anastasi had been looking for a gallery, carting around slides and tape recordings of his new sound work. First, he’d gone to Leo Castelli, among the most revered New York dealers. Castelli’s director, Ivan Karp, said the work was brilliant but “not for Leo.” Then Anastasi went to Pace Gallery, where dealer Arnie Glimcher said, “This isn’t right for us,” but mentioned a new gallery up the street. Anastasi had never heard of Dwan , but was floored by Kienholz’s installation, which included an audio recording of activity at the famed L.A. bar. He hadn’t known anyone else was working with audio.

Dwan looked at his work — minimal, found object assemblages that hung from the ceiling and emitted sounds — and offered Anastasi the third show at her New York space. She had opened in New York with only two shows lined up, since many of the artists she exhibited in L.A. already had East Coast representation.

As she sought out new artists, Dwan’s program shifted — first toward Minimalism, newly gaining prominence in New York, then Conceptualism and Land Art. The shift happened organically. “The artists recommended each other, and they were connected by their ideas,” said Candace.

In 1966, across her New York and Los Angeles galleries, Dwan showed white cubes by Sol Lewitt; playful, boxy pedestals by Robert Morris; steel constructions by Kenneth Snelson; and cast-resin spheres by DeWain Valentine. She became the first gallerist to actively support Land Artists at the time, and her 1968 show “Earthworks” marked the first time that term was widely used. “There were whole new movements that were under the surface, but she brought them forth,” said artist Dove Bradshaw, who is married to Anastasi. “The artists themselves were creating new works for her space.”

Dwan closed the Los Angeles gallery in 1967, focusing all her energy and resources on New York. Artist Charles Ross — who first showed his prisms, acrylic shapes filled with distilled water that refract light and cast color spectrums on the walls, at Dwan Gallery in 1968 — recalled the energy at the New York gallery: “There used to be artists in her office all the time. Everybody dropped by because it was kind of a continuous conversation going on about art and ideas.”

In fall 1969, Dwan purchased the square mile of desert that would become home to Michael Heizer’s defining earthwork “Double Negative.” She helped Robert Smithson secure the 20-year lease he needed for “Spiral Jetty” in the Great Salt Lake in 1970. In 1971, she provided initial support for Charles Ross’ “Star Axis,” an 11-story earthwork, a naked-eye observatory designed to make the geometry of the stars feel close to Earth.

When she announced her decision to close the gallery in 1971, Carl Andre wrote to her: “I feel like a New England hill town which has been told by the Textron Corporation that the plant is being moved South.” In interviews, Dwan said she felt burnt out. “She gave an awful lot of herself,” said Candace, adding that her mother had accomplished what she set out to do. “She had already, in a sense, made her gesture.”

After the gallery closed, Dwan took up scuba diving and enrolled in certification lessons at the YMCA. “We were both taking off on a new path, which involved a different kind of spending of the time,” said singer-songwriter Judy Collins, who met Dwan in the late 1970s when both women were rebuilding their careers. “That took contemplation; it took silence.”

Dwan never stopped supporting artists. She funded Walter De Maria’s “35-pole Lightning Field,” a precursor to “The Lightning Field” installation in New Mexico, as well as work by LaMonte Young, Marian Zazeela and Philip Glass. In 1985, she approached MOCA about donating Heizer’s “Double Negative” to the museum. “We had a lot of opposition on the board,” said Koshalek, then the museum’s director. He did acquire the work and credited Dwan with imagining this kind of art in an institutional collection. “That was her.”

Dwan also returned to making her own creative work, something she had initially abandoned as an undergraduate. She made filmed portraits of artists Carl Andre, John Cage and Mark di Suvero. She spent years photographing military cemeteries across the country, an effort to convey the devastation of war, publishing them in a book called “Flowers “in 2017. Dwan also took up painting, making one series from tree rubbings. “They are really beautiful,” said Candace, who encouraged her mother to exhibit them. Dwan refused, saying she didn’t “want to interfere with the work of the gallery. She wanted that to remain completely untouched or unaffected by anything that she did,” Candace said.

The closest she came to putting her own artwork into the world was with the Dwan Light Sanctuary, opened in Montezuma, N.M. in 1996, a place for contemplation based on Dwan’s vision, and designed by architect Laban Wingert. Ross designed 12 solar prisms for the apses.

“I think she was probably as happy with the light sanctuary as she was with anything else she ever did,” said Collins, who sang at the opening.

In 2013, Dwan donated 250 works from her collection to the National Gallery of Art, an institution she chose for a few reasons, as her longtime collection manager Anne Kovach explained. The gallery is free; it does not deaccession work; and it would keep her collection together. The 2017 exhibition “Dwan Gallery: Los Angeles to New York, 1959-1971” opened at the National Gallery of Art and then traveled to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The show sparked a reappraisal of her contribution, which had too rarely been credited in historical accounts of postwar art movements.

“I don’t think that the art world treated her fairly,” said artist Di Suvero, who first showed with her in Los Angeles. “She could look at work that would’ve been refused by many other art cognoscenti. She had an ability to show people, to help people, and somebody like that, in this greedy society, is very rare.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.