- Share via

Do Angelenos dream of electric billboards?

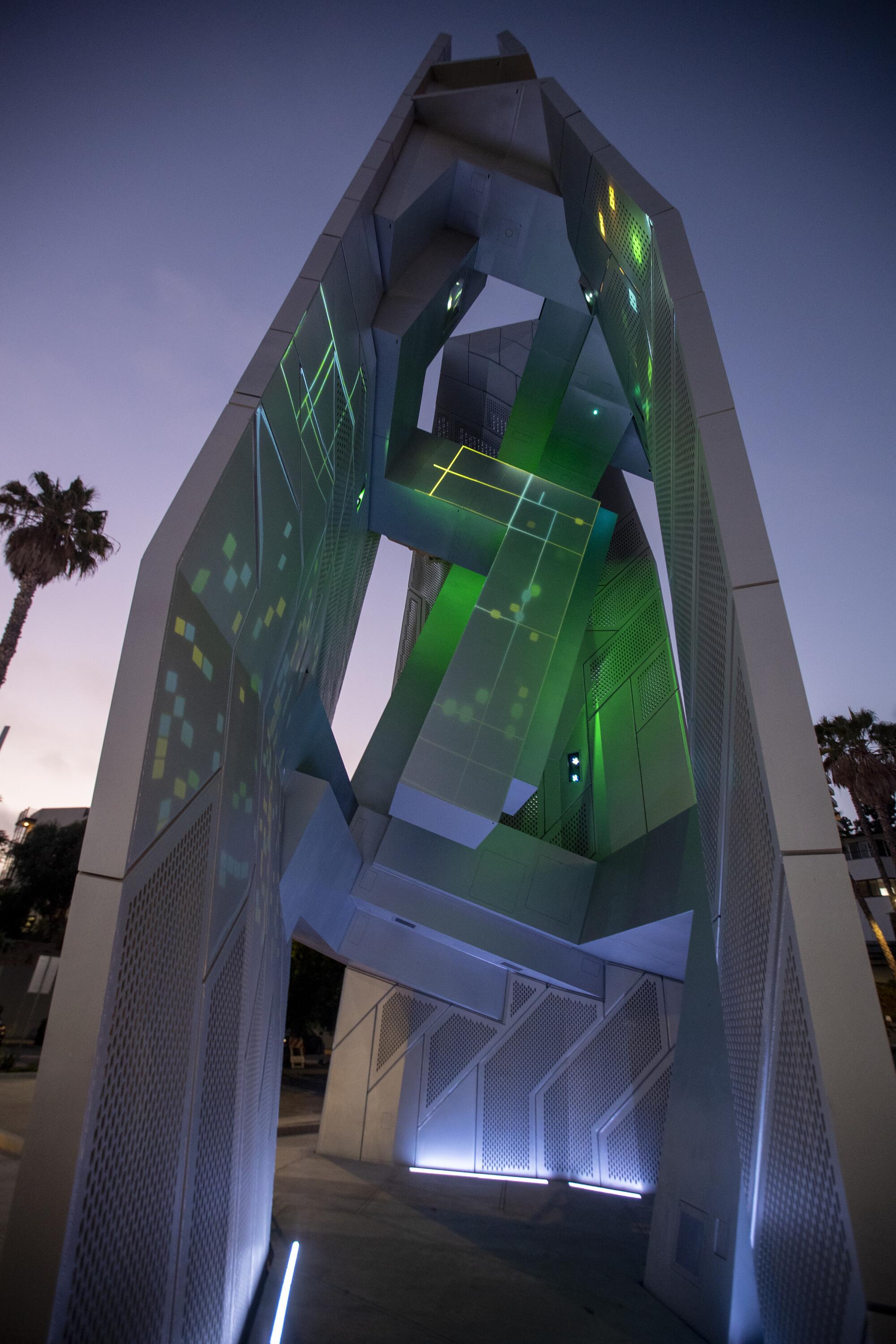

Apparently we do, according to an intriguing report in the New York Times last week — about a digital billboard designed by Los Angeles architect Tom Wiscombe that materialized more than a year ago on the Sunset Strip. And sure, this is not your ordinary billboard. Formally known as the Sunset Spectacular, it consists of a trio of massive steel panels that converge at a height of 67 feet, two of their surfaces draped in irregularly shaped digital screens bearing ads for tech overlords Amazon and Meta. If a game designer for “Halo” were to imagine a billboard, this is probably what it would look like.

In his dispatch for the New York Times, long-time independent critic Joseph Giovannini waxed poetic about the $14-million design, describing the structure as an “inviting chapel” that “fuses architecture, art, media and an interactive pedestrian experience.” At ground level, it is possible to walk through the base of the structure, which after dark is illuminated with internal projections. It also features a soundscape, which on Monday evening had a gooey, amniotic vibe — the sort of thing you might hear at a spa.

Unmentioned in the story was the fact that the architect had been put on administrative leave by the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc) back in March, after students there launched a petition calling for his ouster as undergraduate program chair. Among the allegations that surfaced against Wiscombe, who has taught at SCI-Arc in downtown L.A. since 2006, were conflict of interest, favoritism and the mistreatment of students who worked as interns in his firm. The petition also called for the removal of the school’s history and theory coordinator, Marrikka Trotter, an associate at Wiscombe’s firm (and who is also his girlfriend).

Shortly after the petition emerged, members of SCI-Arc’s administrative faculty echoed the students’ call via a public meeting held on Twitch. This was followed by a separate petition, signed by more than 800 alumni (along with some non-alumni supporters), demanding that student allegations be adequately investigated and that any findings “lead to the development of effective policies for checking and balancing labor issues between faculty and students in the future.”

In late March, SCI-Arc director Hernán Díaz Alonso issued a memo, as reported in the Architect’s Newspaper, announcing that Wiscombe and Trotter had both been put on leave — and that the school was “retaining the services of an external firm to conduct an independent investigation.” Other announced changes included the formation of a working group to examine the structure of internships and policies around scholarships. (One of the allegations was that Wiscombe and Trotter wielded an unusual amount of control over who received scholarship money.)

The investigation has fueled chatter on social media and, in the spring, was the subject of regular articles in the architectural press, with one unidentified source alleging 18 hour workdays at Wiscombe’s studio and duties that included cleaning the office. (At the time, I summarized the roots of the controversy in The Times’ Essential Arts newsletter.)

The scandal isn’t just about Wiscombe or even SCI-Arc. Issues of equitable treatment, pay and working conditions are part of a larger reckoning within a field renowned for hazing its youth with unpaid or underpaid internships, interminable work hours and a culture that has long turned a blind eye to the bullying behavior of artistic “geniuses.” In June, officials at England’s University College London issued a formal apology to students, alumni and staff of the university’s architecture school for a “culture of unacceptable behaviour” after an investigation revealed a “boys club” atmosphere forgiving of misogynistic, discriminatory and antisemitic attitudes — behavior that first came to light as the result of an investigation last year by the Guardian newspaper.

A SCI-Arc panel on the professional aspects of working in architecture has spurred a fierce industrywide debate over acceptable working conditions.

This context makes it extra curious that the controversies at SCI-Arc wouldn’t merit even a passing reference in Giovannini’s story about a 17-month-old billboard.

The omission, naturally, set social media on fire.

“I Genuinely Think It Would’ve Enhanced Readers’ Understanding Of This Project And Its Significance If This Piece Had Mentioned Anyone Else Who Works In Wiscombe’s Office, Including Some Of The Student Workers At The Center Of A Notable Recent Controversy Over Exploitation,” stated a popular Twitter account that operates under the handle @VitruviusGrind.

On Instagram, the anonymous memesters at @dank.lloyd.wright spoofed Wiscombe’s billboard. They also caught an edit to the New York Times story: The original version of the piece noted that Wiscombe taught at SCI-Arc; an update removed the reference altogether.

To many skeptics, it seemed as if the architectural establishment were intent on scrubbing the record clean. Giovannini, a regular contributor to the New York Times and a slew of architectural publications, celebrated Wiscombe’s work in his recent book, “Architecture Unbound: A Century of the Disruptive Avant-Garde.”

When the allegations against Wiscombe first surfaced in the spring, the architect posted an apology to his Instagram account: “I’m aware that I often focus too much on design outcomes and not enough on the environment and community that makes it all possible,” he wrote. “I also tend to be hard on myself and I let that hardness extend to others, which is unfair.”

That apology has since been deleted. But on Tuesday Wiscombe responded to a query from the Los Angeles Times. “One accurate criticism of me is that my expectations are sometimes too high,” he stated via email. “I myself work very hard, and I’m aware that it can be exhausting for my staff. This situation has been a wake-up call for me, and we had a lot of very good, very frank conversations in the office about our office culture.”

He also said his firm, Tom Wiscombe Architecture, began paying interns four years ago. Prior to that, he said, unpaid internships were offered “according to SCI-Arc policy,” with students receiving school credit in exchange for the work. (This included unpaid student interns who worked on the Sunset Spectacular project, which itself began as an unpaid competition in 2016.)

This was a practice, he noted, that “many SCI-Arc faculty did at the time” — adding that “it was part of the school’s culture.”

Certainly, this speaks to the systemic issues at play. Deborah Garcia is an Inglewood native who graduated from SCI-Arc with a bachelor’s in architecture in 2017. She went on to complete her master’s in architecture at Princeton and is now a fellow and lecturer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“SCI-Arc is not alone in this,” she said. “Many schools are facing this.”

I submitted a list of almost a dozen questions to SCI-Arc about its practices. A spokesperson issued only a short emailed statement in response: “The independent investigation is still ongoing. We expect the investigation to conclude and any policy changes to be announced by this fall.”

The Southern California Institute of Architecture is getting it’s first new director in more than a decade.

How did one of architecture’s more radical outposts — the so-called “college without walls” — find itself embroiled in a scandal about student exploitation?

Some of that has to do with SCI-Arc’s roots. Founded in 1972 by architect Ray Kappe and half a dozen fellow educators who were intent on establishing a progressive architecture school in Los Angeles, SCI-Arc did away with traditions such as tenure. The idea was that this would keep the school more responsive to contemporary society.

“Sounds great,” said Garcia. “But it means that the checks and balances for evaluating faculty — and mechanisms for evaluating faculty — they don’t exist.”

And that faculty can hold a great deal of power. A student might study under a professor, then intern for that professor — a professor who might then decide whether that student gets scholarship money, a career-making academic prize, a recommendation letter or introductions to a principal at a prestigious firm.

“There were no boundaries between life’s academic, professional and personal aspects,” said Zaid Kashef Alghata, now based in Bahrain, who graduated from SCI-Arc with a bachelor’s degree in architecture in 2016 before also completing a master’s degree at Princeton. “Anything you did in one affected the other.”

Raymond Kappe was founding director of the Southern California Institute of Architecture, and his designs advanced the benefits of green building.

Students were often told they should be grateful for whatever work they could find, he said. “One of the things a professor told me during my final year was, if you find a firm you want to work for, you should want to do anything — including mopping the floors.”

It’s a culture of scarcity. It’s also a culture of acquiescence — that’s just the way architecture is — and it makes students more accepting of mistreatment, worried that a single complaint could derail their career. For students of modest means, it was even more fraught.

“When you are in a fiscally vulnerable position, your perceptions of value and labor are critically warped,” said Garcia. “Any job, any opportunity, you say yes to — or it becomes very difficult to say no.”

Again, excessive hours and unpaid internships are an industry-wide problem. But SCI-Arc, bereft of a regular review process associated with tenure, may have unwittingly created an atmosphere insulated from student concerns.

Wiscombe, for the record, stated that he never improperly awarded prizes or scholarships or used them as a quid pro quo. “Most of the anonymous complaints against me and my girlfriend, Marrikka Trotter,” he added, “are false.”

The next step for SCI-Arc is the completion of the investigation. Alumni and other architects I spoke with (including off-the-record sources not quoted in this story) hope it might function as a critical reset — not just for SCI-Arc, but for the industry at large.

“SCI-Arc really has an opportunity,” said Garcia. “But whether they’re going to be truly radical, that remains to be seen.”

This whole episode also calls into question how critics (myself included) write about architecture. “Should we promote architecture for purely aesthetic reasons?” said Kashef Alghata. “Should we suppress issues of labor and malpractice in architectural write-ups?”

There is an important story embedded in the design of the Sunset Spectacular. It has nothing to do with its forms.

A 6th Street Bridge Design Diary undermines the hype about chaos, revealing its many uses in a complex urban space. And yes, the bike lanes need work.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.