Review: With Yuval Sharon and Gustavo Dudamel at the helm, ‘Valkyries’ makes history again at the Bowl

- Share via

In 1938, Los Angeles suffered one of the worst floods in its history caused by once-in-a-lifetime storms in February and March. The L.A. River overflowed. Over a hundred people died. The gods were angry.

That summer the Hollywood Bowl staged what is said to be the most spectacular event in its history: a production of Wagner’s opera “Die Walküre,” which chronicles the needs for humanity to save a world being destroyed by greedy, angry, devious, environmentally destructive gods. The then-Bowl shell, which was positioned on railroad tracks, could be moved aside so that for the “Ride of the Valkyries,” the storied young warrior goddesses in armor and horned helmets might gallop down the hillside on horses and onto the stage. A thrilled Walt Disney was in the audience. History was made.

A lot has changed in the last 84 years. But when Yuval Sharon staged Act 3 of what was now advertised as “The Valkyries” on Sunday night at the Bowl, the gods still seemed plenty angry, this being the summer of a record Southland drought. I don’t know whether the Disney Pixar crowd bothered to show up this time around, but Hollywood Bowl history was made again, along with live animation operatic history.

The Los Angeles Philharmonic can no longer move its massive modern shell. The audience doesn’t connect with nature much in what has become a more urban alfresco amphitheater, although it was a pleasant night. No horses, but Valkyries on motorcycles. No hillside, but video screens. The gods have become digital devils. Restoring the world, including the planet we inhabit, has become the job of questionably capable humans.

For the record:

11:00 a.m. July 21, 2022An earlier version of this review said the orchestra had five harps on stage. There were six.

The evening began like this. Gustavo Dudamel and a very large orchestra (six, count ’em, harps) were on stage. Behind the orchestra was a green backdrop and small platform for singers. On the video screens, Sigourney Weaver materialized to fill the audience in on what had transpired thus far in Wagner’s “Ring,” “The Valkyries” being the second in the four-opera cycle.

In her telling, the gods operated on the digital plain and the system had “a ring-shaped flaw” that the head of the gods, Wotan, needed to wrest from an evil dwarf. This act revolves around his favorite daughter, Brünnhilde, whom he banishes from the gods for disobeying her father even though she was only doing what she knew he wanted deep down.

Love, Weaver tells us, is, for the daughter, always greater than the law. Love, for the patriarch, must always obey the law. “Little does Wotan know that Brünnhilde was the hero he was looking for,” she says in the video.

Helmeted Valkyries in flamboyant costumes began to walk onto the small stage. Men in green body suits helped guide them into place. But they were essentially just singers on stage, doing their usual Wagnerian business in following Dudamel and acting some.

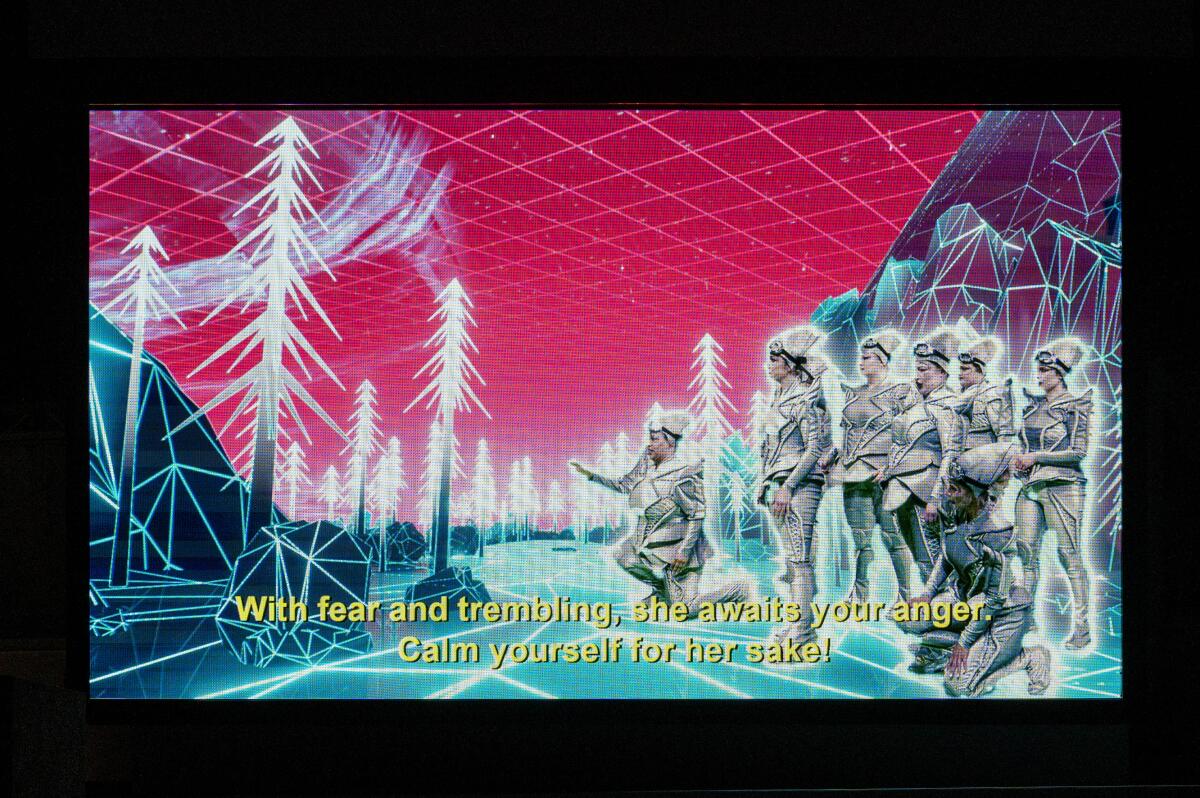

On video, thanks to green-screen technology, they were transported to an animated digital wonderland. They hopped on futuristic motorcycles and rode through a landscape that looked like it might have been designed by Buckminster Fuller, he of the geodesic domes. They raced through space with urns on the back of the cycles, the Valkyries’ main job being to bring dead warriors to Valhalla, Wotan’s mountaintop castle, which he paid for with ill-begotten gold.

In the program notes (which you can access only digitally, that being the current way of the Bowl), Sharon likens this to a live video game. The opera exists on two planes. What you saw on stage was traditional. Dudamel and the orchestra presided over Wagner on a magnificent scale. Christine Goerke as Brünnhilde and Matthias Goerne as Wotan provided big-voiced Wagner, as did the other Valkyries.

None of this is exactly new. Sharon — founder of the experimental L.A. opera company the Industry — first came to L.A. as assistant to Achim Freyer, when Freyer staged Los Angeles Opera’s revolutionary “Ring.” In Germany, Sharon has staged “Walküre” for Karlsruhe Opera that included use of fanciful prerecorded video.

Sharon’s production of Wagner’s “Lohengrin” for the Bayreuth Festival also questioned Wagnerian patriarchy and actually had a grass-covered green man on stage. During his three-year stint as the L.A. Phil artist collaborator, Sharon experimented with green-screen technology in a staging of Andrew Norman’s children’s opera “A Trip to the Moon.”

Even so, for all the unreal landscape with eye-popping turquoise and purple mountains, red sky and unusual way the opera characters popped up — at one point a tiny Brünnhilde looked like Tinkerbell standing in Wotan’s gloved palm — this was absolutely traditional Wagner. Indeed, Goerke and Goerne can come across as old-school Wagnerians, alike enough that the names of the American soprano and German baritone differ in but one letter. Goerke impressed at first with the sheer volume of a rich, arena-filling voice. The stern Goerne was cold and imposing. They were mythic, unreal in an unreal landscape.

But each gradually revealed a vulnerability. Wotan knows the game is over, and Goerne made his farewell to Brünnhilde a farewell to life. He is the true broken immortal who must keep up appearances. Goerke too can no longer rely on a too-easy Valkyrie bluster. She must now become a far more impressive mortal hero. Watching her take in what it means to really be alive, with video close-ups, demonstrated just how much we kid ourselves with artificial digital reality.

What Sharon, in the end, accomplishes through this whiz-bang technology is just that, the appreciation that there is more to life than video screens, that they must not control us but open our eyes to the real world around us. Just as it is impossible not to look at the Bowl screens, it was impossible not to look at the real orchestra and real singers.

Not everything worked. The subtitles, small and in yellow, were difficult to read. A strong cast included necessarily mighty Valkyries, but Amber Wagner’s Sieglinde would have had a better chance being effective were she singing several decibels softer.

Sharon’s 17-member production was larger than the cast, an array of designers and technical artists. With extremely limited rehearsal time at the Bowl, they produced a miracle. Though a one-night miracle here, this is a co-production with Detroit Opera, where Sharon is artistic director, and which will present it for three performances in September. Wagner’s gods have got something to be happy about.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.