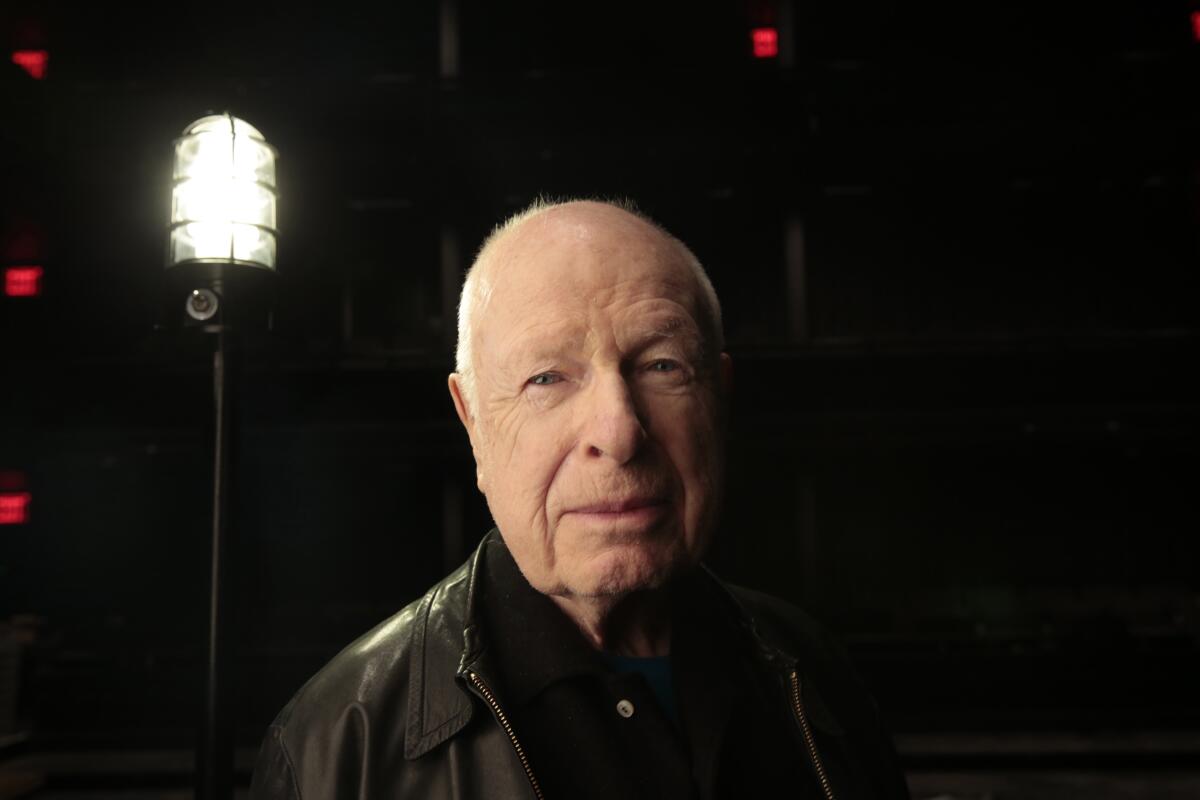

Appreciation: The radical majesty of British theater director Peter Brook

- Share via

I’ve been fortunate to have met a number of geniuses in my years as a theater critic but only one who was a true sage.

Peter Brook, the British director who revolutionized the way Shakespeare was staged in the postwar era, never rested on his laurels. After ushering the classical British theater into the 20th century of Edward Gordon Craig, Bertolt Brecht and Antonin Artaud, he left England for France to establish the International Centre for Theatre Research, one of the most innovative groups for intercultural performance in the world, long situated at the Bouffes du Nord in Paris.

Indeed, Brook lived and worked in a continual state of becoming. Even in his last decades, when he might have basked in the eminence of his international reputation, he was still experimenting, still trying to separate the essential from the meretricious.

Brook’s death at age 97 marks the end of a theatrical era. His work, weaned on modernism, liberated by postmodernism and forever revisiting the classics, cared little about aesthetic ideology but was deeply rooted in history. Whatever comes after Brook, it is doubtful that it will be as consciously linked to the breakthroughs and summits that defined theater directing in the modern era as an art form in its own right.

As much revered by the establishment as he was by the avant-garde, Brook was a recipient of three Tony Awards. Yet he was more in his element when working away from the commercial glare of Broadway and London’s West End.

His productions synthesized the watershed movements of 20th century theater. The contemporary examples of Irish playwright Samuel Beckett and Polish theater director Jerzy Grotowski were as palpable in his work as the influences of Craig, Brecht, Artaud. But his deepest debt was not so much to the aesthetic achievements of these pathbreaking artists as to their revolutionary determination to make the stage once again a vehicle for discovery.

When I interviewed Brook at San Francisco’s American Conservatory Theater in 2017, he was 92 years old and on tour with “Battlefield,” a production distilled from his marathon magnum opus, “The Mahabharata.” His voice was meek but his mind retained its formidable clarity. Bundled in a scarf against the threat of an indoor breeze, he spoke effortlessly yet unhurriedly, his words flowing steadily as they lighted a path deeper into the core of his twin obsessions — art and existence.

Brook was one of those rare divines, to borrow Portia’s metaphor from “The Merchant of Venice,” who followed his own instructions. The wisdom he exuded was that of a man on a perpetual quest. His approach to theater, mirroring his attitude toward life, was exquisitely — and undogmatically — attuned to the present moment.

A central tenet for him was that “truth in the theater is always on the move” and therefore must be pursued afresh. Tradition was a valuable instrument in the chase, but it could also be a trap.

In his indispensable treatise “The Empty Space,” Brook divided the modern theater into four categories: deadly, holy, rough and immediate. The deadly theater, the commercial branch that’s built around box office and awards, “approaches the classics from the viewpoint that somewhere, someone has found out and defined how the play should be done.” But for Brook, not even the playwright was granted the final word. As countless moribund encounters with “faithful” productions made clear to him, “If you just let a play speak, it may not make a sound.”

Although he found inspiration in the roughness of Brecht’s political theater and the metaphysical mysteries of Artaud’s holy theater — and memorably integrated their disparate visions in his landmark 1964 production (and 1967 film) of Peter Weiss’ play “Marat/Sade” — his own proclivity was for what he called the “immediate” theater, which derived its vitality from the dynamism of collaboration. Most important to Brook was the relationship between artist and audience, a partnership of equals, separated by “practical” rather than “fundamental” differences.

For Brook, “The artist is not there to indict, nor to lecture, nor to harangue, and least of all to teach. He is part of ‘them.’” A “vital theater,” he believed, must be rooted in a community, even if today’s fractured society has made this possible only on a diminishing scale.

Peter Hall, another British directorial titan, records in his published diaries Brook’s revealing answer to a question about the type of performers he was interested in: “He wanted actors whose main motivation was not being actors. Acting for them was a means to an end,” Hall wrote. “Well, what was the end? Social? Political? Aesthetic? Challenged, he came down to a mystical endorsement of truth: Within the theatre truth burns between performer and audience.”

Brook came into prominence by rethinking the way Shakespeare was revived. At Stratford, he made his name by treating what were then considered lesser plays — “Titus Andronicus,” “Love’s Labour’s Lost” — as though they were new works. “Romeo and Juliet” was tackled with a youthful vigor and violence that proved shocking to those expecting the customary declamatory elegance.

His production of “King Lear,” starring Paul Scofield (subsequently adapted into an experimental film), brought a Beckettian lens to Shakespeare’s formidable tragedy. Brook trusted that, after the horrors of World War II and the rising threat of nuclear annihilation, audiences were up to the challenge of the play’s apocalyptic vision and its understanding of evil as something recognizable in human nature.

In an interview with director Richard Eyre, Brook explained what he was after: “I think that what was quite clear was that ‘Lear’ had suffered like all the other plays from tradition. … Because we hadn’t got a true Elizabethan tradition: we had at that time a very, very bad Victorian tradition that took you far away from the plays,” Brook said. “It had put a wrong pictorial stamp on the plays and a wrong moral stamp, because the Victorian tradition told you very strongly who were the good and who were the bad people.”

Brook’s cobweb-clearing 1970 Royal Shakespeare Company production of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” famously ditched the forest scenery for a white box and circus trapezes. Reactions to the daredevil antics were split, but imagination — a central theme of the play — was rekindled. It’s fair to say that Shakespeare was catapulted into the modern era with a staging that was a celebration of both the childlike wonder and mature virtuosity of the art of theater.

“The Mahabharata,’’ Brook’s epic production created with co-director Marie-Hélène Estienne and dramatist Jean-Claude Carrière, theatricalized for Western audiences the vast Hindu epic. The nine-hour work, a culmination of Brook’s directorial investigations and experiments, was heralded as a masterpiece when it premiered at the Avignon festival in France in 1985. But charges of cultural appropriation were leveled by critics who felt the spectacle of exoticism dehistoricized sacred myths.

Brook refused to let this criticism deter his intercultural commitment. He was adamant in his 2017 interview with me that his position had remained unchanged: “Shakespeare is played in every part of the world. It comes from England, but the English have never said that it belongs to us exclusively,” he said. “When I first encountered the poem, I saw that this was one of the masterpieces of humanity, but for complicated historical reasons it had hardly emerged from India. I felt, and this is a pure piece of romantic imagination, that we had been called to be the servants of the epic ...”

But if Brook had no misgivings about his approach to world culture, he grew less enamored of working on such a monumental scale. His late works were born out of the desire to communicate from a place of bare theatrical necessity.

In “The Man Who,” inspired by Oliver Sacks’ “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat,” Brook tackled the mysteries of the brain in a compact 100 minutes. He staged “Hamlet” with eight actors, no intermission and roughly a third of the original play cut — raising the hackles of purists just as his scaled-down version of Bizet’s “Carmen” had done decades earlier. He gravitated quite naturally to Beckett’s briefest works. Even “Battlefield,” derived from “The Mahabharata,” was a mere 70 minutes.

Although he was effortlessly eloquent, Brook understood that speaking about artistic work wasn’t the same thing as doing it. “I really don’t see it in terms of accomplishments or achievements,” he said when asked by an interviewer about his career. Up until the end, his imagination was ignited by the infinite possibilities of empty space.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.